“An investigation of the cause, circumstances and origin of a fire which occurred in Hartford on July 6, 1944 during the circus performance at the Ringling Bros.—Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows, Inc. was instituted by me … to determine whether such fire was the result of carelessness or the act of an incendiary.”

Arson was not foremost in the minds of the investigators as they walked through the charred remains of the big top in the days after the tragedy. Rumor spread that the cause of the fire was a cigarette or a match carelessly thrown onto dry grass covering the circus grounds or against the side wall of the tent. Police officer McAuliffe could not find the man who’d mentioned the cigarette to him. In McAuliffe’s original report, he records the man’s statement as “some dirty son of a bitch tossed or dropped a cigarette,” which sounds more like the man was guessing than reporting something he had actually seen. In Commissioner Hickey’s report, the statement is misquoted and sounds more accusing—“That dirty son-of-a-b---- just threw a cigarette butt!” The missing witness’s remark could not be verified, but it had a huge impact. It was one of the things that led investigators to focus on an accidental cause instead of an intentional one.

Commissioner Hickey led a formal investigation after the fire. He leaned heavily on the cigarette theory. New York fire marshal Thomas Brophy, an expert in fire investigations, was called in. In his opinion, a carelessly dropped match or cigarette could have started the fire, but he also said he did not know the physical conditions at the time or whether there was any other flammable material near the location of the fire. He found that one of the wooden supports for the bleachers was badly charred at the bottom. A cigarette or match itself could not have ignited the support, but if the side wall of the tent was ignited first, it could have caused the support to catch fire. With so many variables and without a witness, Brophy could not make a definite conclusion.

Kenneth Gwinnell, an usher, made a statement to police in which he said it was common for cigarettes and discarded matches to start fires. He suggested that “a cigarette would have smoked for a while, but [the fire] came all of a sudden and it evidently was a match.” Whether it was the cigarette itself or the match used to light it, Gwinnell’s statement supported the idea that the fire was accidental.

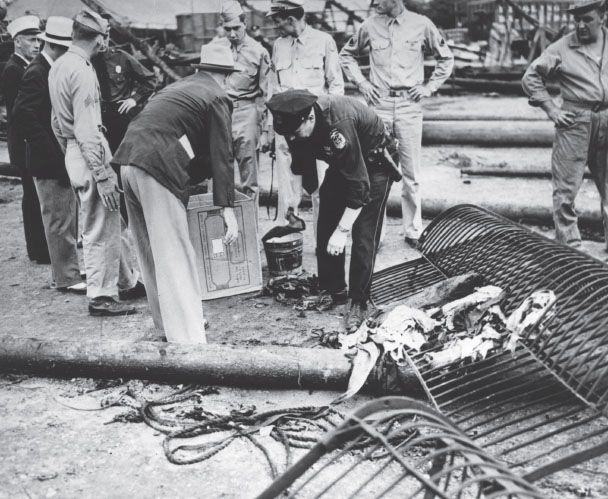

Police detectives inspect the scene of the fire.

Commissioner Hickey defended his theory in an interview with the Hartford County coroner, Frank E. Healy.

Coroner: “Supposing your chemical analysis of the side walls of that tent show that a cigarette under full force would not ignite that canvas?”

Commissioner: “My answer to that would be based on the testimony before me, that consideration has got to be given to the dry ground, the condition of the ground, the manner in which the side wall canvas was hanging folded over on the ground, and the manner in which the cigarette or burned match landed on the combustible material.”

Witnesses to the blaze, however, told a different story. They reported that the fire had started high up on the tent side wall, not on the ground. Jane Pelton, age 12, said, “At about the end of the animal [act], just as the animals were leaving the cage, someone shouted help. I looked back to my right and saw a large flame at the beginning of the roof of the tent.” Helen Fyler, age 40, saw “a patch of flame about 6 or 8 feet wide at the point where the side wall meets the tent top.” And Joseph Dewey, age 10, said, “I sat … about two seats from the top. While we were looking at the animals in the cage doing tricks, I heard someone say the tent was on fire. I looked back and I saw the fire where the tent bends over above the bleachers. This fire was just starting and there was a little hole in the tent…. I didn’t see any fire along the bottom of the tent when we came out.”

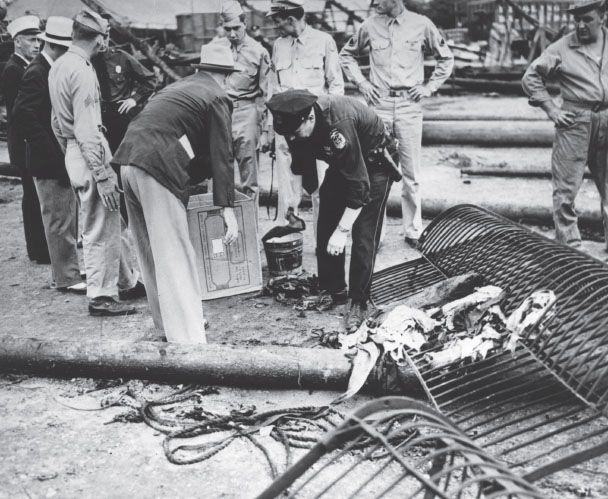

This photo seems to show the origin of the fire, above the small tent that housed the men’s restroom.

In fact, Commissioner Hickey contradicts himself when, in his own report, he notes, “Many patrons for the first time saw the fire burning the upper portion of the side wall canvas and the lower section of the top adjoining the side wall canvas.”

Investigators from the Hartford police questioned and took statements from countless circus-goers and members of the Ringling Bros. staff. No one seemed to know how the fire started. A few employees had criminal records, and some were investigated on suspicion of arson. They were all dead ends.

Commissioner Hickey based his conclusions almost exclusively on the testimony of two men: Kenneth Gwinnell and Daniel McAuliffe. Neither man had actually seen how the fire started. Both of their statements relied on assumptions and hearsay.

Commissioner Hickey issued his final statement: “Upon the testimony before me, I find that this fire originated on the ground in the southwest end of the main tent back of the ‘Blue Bleachers’ about 50 feet south of the main entrance, and was so caused by the carelessness of an unidentified smoker and patron who threw a lighted cigarette to the ground from the ‘Blue Bleachers’ stand. The evidence before me does not disclose this to be the act of an incendiary.”

The case was closed, and the cause of the Hartford circus fire was declared accidental … until six years later, when Robert Segee, the teenage member of the lighting crew, confessed to setting it.

Burned bleacher seats.

Now Segee was 20 years old, and he was in police custody on suspicion of setting a fire at a factory in Circleville, Ohio. As police detectives questioned him, the young man admitted to setting fires in Circleville and Columbus, Ohio, as well as in Portland, Maine. He also confessed to setting the circus fire in Hartford, Connecticut.

Commissioner Hickey was angry when he heard the news. It looked as though the police in Columbus, Ohio, were going to crack his case. What’s more, Hickey would look pretty bad if they revealed that he was wrong about the fire being an accident. Hickey sent police captains Paul Lavin and Paul Beckwith to Ohio to question Segee in relation to the Hartford fire, but when they arrived, authorities turned the investigators away. They said the reports were not written up yet, so they couldn’t share their findings. Furthermore, the Hartford detectives could not interview Segee because the Circleville case was still open. In a letter to Commissioner Hickey, Lavin wrote: “It appeared throughout our investigation that these two gentlemen [Ohio detectives R. Russell Smith and LaMonda] want to get the credit of breaking the Hartford case as well as the cases in their own jurisdiction to build the prestige of their own office and division.”

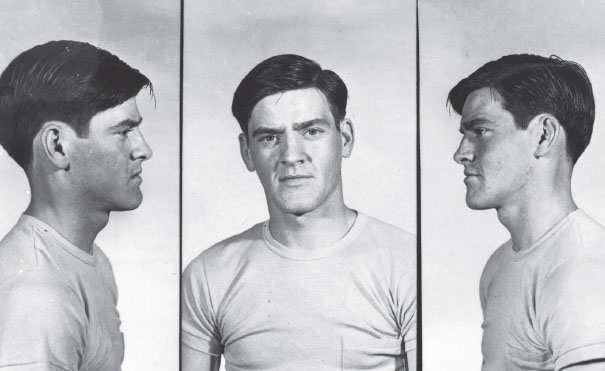

Robert Segee at age 20.

Commissioner Hickey was livid. In snappish back-and-forth phone calls and telegrams Hickey blamed authorities in Ohio for not sharing information about Robert Segee, and the Ohio authorities told Hickey to stay out of the way of their investigation.

Meanwhile, Ohio investigators pulled together details about Segee’s past. They interviewed Robert’s mother, Josephine Segee, and Dorothy Segee Thompson, his sister. According to Josephine, Robert’s father “was always very mean to Robert. The boy was very sensitive and [he] would leave home every time his father would [holler] at him.” Josephine told the investigators that as a child, Robert was afraid to go to bed because he was constantly plagued by bad dreams. At nine years old, Robert roamed the streets at night rather than face the nightmares. In the interview, Robert’s mother said, “I never had any idea that Robert was setting any fires. I knew there was something wrong with him but you know how a mother is—I never wanted to admit it.”

Dorothy, on the other hand, knew Robert had acted out in dangerous ways. She remembered her brother setting two fires at their house, one of which occurred when, at age five, Robert had thrown a newspaper onto an oil stove. Over the course of six years, 68 suspicious fires were reported within 10 blocks of the Segees’ home. Could Robert have set those fires?

When Robert had joined the Ringling Bros. circus in June of 1944, perhaps he had hoped to escape his troubles. Instead, it appeared things had gotten worse.

Now, Ohio investigator R. Russell Smith and psychologist Dr. Bernard Higley interviewed Segee. During the interview, Segee described visions he’d had of a Native American he called “the red man.” He said that this man had told him to start the fire at the circus in Hartford. Segee made several drawings during his mental evaluation. Most reflected his Native American heritage. Some were peaceful scenes: birds soaring over wooded landscapes; a man canoeing down a river. But Segee also drew pictures of his most disturbing visions, including the face of a woman engulfed in flames that admonished him for setting the circus fire. “You are responsible,” he claimed the vision had told him.

Segee admitted to setting the fire in Hartford, but he also said he did not remember doing it. He claimed that before the show, he’d been downtown on a date. When the girl rejected his advances, he went back to the circus grounds to take a nap. “I laid down and went to sleep and then there was the strike of the match again and the red man came,” he related. “[I saw] a small flame and then it turned into this red man again and then the red man became a red horse and then I remembered somebody shaking me and when I came to I was standing on my feet with my clothing and shoes and stockings on and I ran in and tried to help with the people.”

Throughout his interviews with Ohio authorities, Segee appeared remorseful, almost tearful. He claimed he was plagued by the visions that told him he had set the fires and was the cause of the victims’ pain. He maintained throughout questioning that he did not remember setting the fire, but he felt his visions and mental anguish meant that surely he must be to blame. It appeared that Segee had difficulty distinguishing between his bad dreams and reality.

Was Segee guilty? He was known to set fires as a child and was about to be convicted for the Circleville fire. He had been at the scene of the crime. He had even confessed to setting the Hartford fire. However, the fact remained that no one had seen Segee set the circus fire. He himself said he did not remember doing it, and his unstable mental state made his admission of guilt dubious.

And then, on November 17, 1950, Segee recanted his confession.

Around this time, police in Scituate, Massachusetts, were eyeing Segee as a murder suspect. Two police sergeants were sent to interview him in prison to find out if they could connect him with the murder. They questioned him about his activities prior to the Hartford circus fire. During the course of the interview, Segee told the officers that he was not to blame for any of the fires he was accused of setting. He had never set a fire in his life, he said. Segee claimed that the accusations against him were based on his vivid dreams and imagination, rather than what he’d actually told investigators in Columbus. Segee now said he had not been on a date or returned to the grounds to take a nap before the fire started as he had previously stated. Instead he said that on the day of the circus fire, he and a friend had been downtown watching a movie. When Segee and his friend returned, the tent had already burned to the ground. He said they were questioned by officers and released. Segee was firm. He did not do it.

After Segee completed his prison sentence for the fire in Circleville, he was evaluated by another psychiatrist. The doctor diagnosed him as a paranoid schizophrenic and committed him to the Lima State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Ohio.

Commissioner Hickey never got to interview his suspect, but the Ohio detectives hadn’t cracked the case, either. The cause of the Hartford circus fire remained “accidental” for the next four decades—the prevailing theory: a carelessly discarded cigarette.

Lieutenant Rick Davey, an arson investigator for the Hartford fire department, had ferreted out the causes of thousands of fires during his career. He once boasted that every arson case he’d ever sent to court ended in a conviction. Though easygoing and soft spoken, he also had the determination of a salmon swimming upstream. People who have met him have called him tenacious and driven. If anyone could resolve the decades-old Hartford circus fire case, it was Davey.

Like most people who grew up in Hartford, Davey knew the story of the circus fire. But unlike those who casually read the news stories that reappeared on the anniversary every year, Davey had specialized knowledge. The idea that a carelessly tossed cigarette could have started the circus fire just didn’t make sense to him. He wondered about factors such as the speed and temperature at which a cigarette burns, how much humidity was in the air that day, and whether a cigarette or even a used match dropped on dry grass really could catch fire.

Determining the true cause of the Hartford circus fire became a hobby for Lieutenant Davey. For nine years he studied the case in his spare time, spending countless hours at the archives of the Connecticut State Library, where boxes of materials related to the circus fire are housed. He collected evidence: photographs of the charred remains of the big top, weather records, and witness statements.

Davey dug through the reports from the state fire marshal and the mayor’s special Board of Inquiry, and he reviewed the opinion of Thomas Brophy, the fire investigation expert from New York. The documents all discussed the possibility of the fire having been started by a carelessly tossed cigarette or used match. Commissioner Hickey’s final report stated the fire started on the ground. Yet clearly it had started higher up on the tent wall, based on the hundreds of witness statements and supporting forensics. Davey felt that Hickey’s report was wrong. There was no evidence that a cigarette had started the fire. In fact, Davey thought it very unlikely.

Davey wrote a report containing all the information he’d discovered and presented it to investigators at the Hartford fire marshal’s office. Eventually the case was turned over to the Connecticut forensics laboratory. There the criminalists performed experiments, analyzed the data, and found the following:

It was too humid on July 6, 1944, for a cigarette to start a fire.

It was too humid on July 6, 1944, for a cigarette to start a fire.

The grass around the big top had been cut just three days before; the trimmings would not have been dry enough to catch fire from a cigarette.

The grass around the big top had been cut just three days before; the trimmings would not have been dry enough to catch fire from a cigarette.

The charring patterns on the bleacher seats where the fire started indicated that the fire was burning from the top, not from below on the grass.

The charring patterns on the bleacher seats where the fire started indicated that the fire was burning from the top, not from below on the grass.

The grass under the bleachers was not burned.

The grass under the bleachers was not burned.

Their conclusions showed that a carelessly tossed cigarette did not start the Hartford circus fire.

Then how did it happen? Davey had another theory. He believed the fire was an act of arson—and he believed that Robert Segee, despite taking back his confession, had done it.

During his investigation, Davey had read the 1950 interviews with Robert Segee and the Ohio State Police reports that detailed Segee’s confession. Unfortunately, Segee’s mental instability made him an unreliable suspect, and there was no physical evidence that he had set the fire. When Segee recanted his confession, he claimed that he had been “harassed” into saying what the psychiatrist wanted to hear. But Davey knew the signs of an arsonist. He thought there was a good chance Segee was the one who had set the fire.

When Davey presented his report, Hartford police reopened the case and assigned Sergeant James Butterworth and Detective Bill Lewis to examine Segee as a suspect. Now 61 years old, Segee still denied setting the fire and told police and reporters to leave him alone. “The confession is not true,” he told the Hartford Courant in 1991. “I really can’t talk about this.” Segee was unhappy that his name was being dredged up again as a suspect. “It’s been very bad on me, and it was unjustified.”

Butterworth and Lewis examined the suspect files for Robert Segee and read through the interviews from the investigation and Segee’s mental evaluation in 1950. Lewis learned that the movie Segee claimed to have been watching downtown, The Four Feathers, was not playing at the time. Was Segee lying about his whereabouts at the start of the fire? His mental state may have been questionable, but Segee was definitely a strong suspect.

In March 1993, Butterworth and Lewis interviewed Segee at his home in Columbus, Ohio. Segee’s daughter Carla was also there, supporting her father during the taped interview.

On the recording, the tone of the interview is friendly. The detectives assure Segee they have no evidence linking him to the Hartford fire and that they are merely there to find out the truth. Segee claims to want to tell the truth and to clear his name once and for all. At times during the interview he appears to plead with the detectives to believe him and says they’re his “only chance.”

Lewis and Butterworth ask questions about Segee’s role in the circus and try to establish his whereabouts before, during, and after the fire. Segee tells the detectives that he worked for the lights department, where he was in charge of the big spotlight. On the afternoon of July 6 someone else took his place so he could go downtown to the movies. Unlike his statements in 1950, Segee now says he attended the movies alone and was not on a date or with a friend.

After the movie, Segee says, he got on the city bus, where he heard about the fire. When he got off at the circus grounds, the big top had already collapsed. Detective Lewis shows Segee a newspaper article from the days after the fire stating that Segee had been burned during the circus fire. But how could that be, if Segee was at the movies? Segee does not address this contradiction in the interview.

Segee tells Lewis and Butterworth it was at least a week after the fire before he was able to leave Hartford. “We was scrutinized pretty closely by the police department and things like that because of the fire,” he tells them. According to Segee, the police questioned him, but only about where he was at the time of the fire, to which Segee responded he was downtown at the movies. Though the state archives have several thick folders of statements from circus employees, witnesses, police officers, and detectives, there does not seem to be a written statement from Robert Segee. In fact, there is no record of the police ever questioning Segee in the aftermath of the fire.

As the interview goes on, Segee’s credibility becomes increasingly weak. When asked about his conviction in setting the fire in Circleville, Segee says he did not do it. He blames the politicians in Ohio for railroading him in order to get elected. “They wanted to clean the Goddamn book. So I was the perfect patsy.” He goes on to blame Ringling Bros. for setting the fire in Hartford in order to collect the insurance money. Segee’s tone makes it clear that he felt like everyone was out to get him.

Detective Lewis asks Segee about his visions and the pictures he drew while he was at the psychiatric hospital. Segee states several explanations: he did not draw them; they were falsified; if he did draw them, they actually reflect a vision of a battle in the late 1700s when Europeans set fire to the open plains after a fight with the Native Americans. The detectives ask about the “the red man” who Segee had said in his 1950 confession had told him to set the fire. “That don’t mean nothing,” Segee asserts on the recording. “They [the psychiatrists] made me do it…. Like I told ya, they messed with my brains.”

And here is where the detectives probably realized they would never be able to pin the fire on Segee. Carla is heard on the recording: “You see, gentlemen, my father is Native American, and within the Native American community … as a holy man, as a shaman, yes, he has visions, but, a lot of times visions can be induced by talking to, in certain ways, where you would think you have seen this, or you have experienced this, but it actually did not come to pass.”

Near the end of the interview, Segee seems tired and quieter than he’d been at the beginning. He again pleads with the detectives to believe him. He insists he is telling the truth about not setting any of the fires. The detectives maintain their even-handed tone throughout the interview, but they must have known they would not be returning to Hartford with any answers.

Butterworth: “I think the final question to ask, to nail this down is, did you start the Hartford circus fire?”

Segee: “No, sir. No, sir, I did not. I wasn’t, I wasn’t even on the grounds.”

In the end, the Hartford police detectives were unable to make a case for arson. “With as many people that were there, no one saw anyone start this fire,” Detective Lewis said following the interview with Segee. “Could it have been an arson fire? Our finding is undetermined. I have no evidence that it was an arson fire.”

On June 30, 1993, the reexamination of Robert Segee in the case of the Hartford circus fire was closed. On August 10, because of Lieutenant Davey’s research, the cause of the fire was officially changed from “Accidental” to “Undetermined.” Though investigators all agreed that a carelessly tossed cigarette was not the cause of the fire, they still did not have any proof of arson.

Robert Segee died in August 1997. The cause of the Hartford circus fire, one of the most horrific disasters in New England’s history, remains a mystery.