“The eight-year-old who was partial to hair ribbons, cats and dresses has been known worldwide as Little Miss 1565…. Her name was Eleanor Cook.”

Detectives Edward Lowe and Thomas Barber stood over the grave of Little Miss 1565, flowers dangling from their hands. The year was 1956. Twelve years had passed since the fire, and the identity of the little girl was still a mystery. Years before, the detectives had made a statement in the Hartford Courant, asking the community for help.

Somebody, somewhere must have cared enough for that little girl to take her to see the circus. In her own neighborhood, there must have been playmates, milkmen, grocery clerks, mailmen, and adults who noticed that some little girl was missing from their everyday lives. It just doesn’t seem possible that a child like that little one could disappear from her own small world without somebody noticing that she had gone and never come back.

In all this time, they’d gotten few leads. Her morgue photo had circulated in newspapers across the county. In 1948, a woman from Michigan saw the photo and was certain Little Miss 1565 was her granddaughter whom she hadn’t seen in four years. She informed the police, and the Detroit Times announced that Little Miss 1565 had been identified. However, soon after, the missing granddaughter and her mother called to say they were alive and well.

Someone suggested she was possibly a girl named Barbara Bluett from Hartford, and a friend of Detective Lowe said he thought Little Miss 1565 was his niece, Judith Berman. These turned out to be dead ends too.

Meanwhile, Donald Cook had grown up. He had never forgotten about his sister, Eleanor, who was lost in the circus fire. His mother kept up the hope that one day her daughter would appear at the door, but Donald knew she was never coming home. In fact, he had a theory. He believed that Little Miss 1565 was his sister.

In 1955, Donald was now 20 years old. He went to the Connecticut State Police and told them what he thought. But the case had been closed, and he got nowhere. Then, in a stroke of coincidence, he spoke about his family’s tragedy with a coworker, Anna DeMatteo. She was struck by the sadness of his story and by his theory about Little Miss 1565. To her, it seemed believable. A year later, DeMatteo became a police officer in Connecticut, and she decided to look into Donald’s story further. Unfortunately, after bringing the matter to her supervisors, she was unable to get them to reopen the case. The following letter to Officer DeMatteo shows a clear misunderstanding that must have been frustrating for her and for Donald.

Your report was reviewed by Chief Michael J. Godfrey, who recalls the persons involved in your report, and he personally talked with Mrs. Cook at the time of the fire.

The young man Donald, who gave you this information, must be misinformed because Mrs. Cook did lose a child in the Hartford circus fire, but it was a boy instead of a girl. Identification was made.

This matter can now be considered closed.

The officer is obviously referring to Donald’s brother Edward, and makes no mention of Eleanor.

DeMatteo and Donald had hit a roadblock, but they didn’t give up. In 1963, they tried again to connect Little Miss 1565 with Eleanor. In a long interview, Donald told DeMatteo everything he knew about the day of the fire and the attempts to find his sister during the aftermath. He explained that his family never discussed the tragedy because it was too painful. Eleanor was “the apple of their eye.”

DeMatteo knew that Emily Gill said Little Miss 1565 was not Eleanor because she believed Eleanor had eight permanent upper teeth. Because permanent teeth generally grow on the top and bottom of the mouth in sets, having eight upper teeth would probably mean there are also eight lower teeth. If Emily were right, Eleanor would have had a total of 16 permanent teeth. Donald believed this could not have been true. Most children Eleanor’s age have four permanent incisors (the top and bottom front teeth) as well as four permanent molars. Eleanor was too young to have had as many as 16 permanent teeth.

In the course of the interview, DeMatteo brought out a picture of Little Miss 1565. Donald had never seen the morgue photographs before. Now he took a long look. This little girl looked similar to his sister, he thought. Her teeth looked different than Eleanor’s, but they had been damaged when the body was trampled during the fire. He thought the hair looked similar. The face looked the same, but Eleanor’s “cheeks seemed rounder” in life. DeMatteo wrote in her notebook that Donald appeared shaken at viewing the photos of Little Miss 1565. Was it possible that he was looking at a photo of his long-lost sister?

Let’s talk to Aunt Marion, Donald suggested. She’d raised the children for several years. Besides his mother, Marion knew the children best. Donald didn’t want to show the photos to his mother yet because he wasn’t absolutely sure his theory was true; he didn’t want to cause her any more pain.

According to Donald, Aunt Marion had a sharp tongue. She seemed to be all business, the opposite of emotional Aunt Emily. When she met with Officer DeMatteo, she confirmed that the girl she’d seen at the armory back on July 6, 1944, was definitely not Eleanor. Her hair length had been wrong. The little girl had all but two baby teeth. Eleanor had eight permanent teeth, four upper and four lower. Marion clearly recalled that the little girl at the armory “had on a white dress, hardly touched by the fire at all.” Eleanor did not own a dress like the one on the body. She believed Eleanor had been wearing a red playsuit on the day of the fire.

Officer DeMatteo spread the morgue photos of Little Miss 1565 on the table. There was silence, and Marion’s eyes filled with tears. Marion thought the hair, the forehead, the shape of the eyebrows, the distance between the eyes, all looked like Eleanor. “This isn’t the same little girl that I saw [at the armory],” she told DeMatteo. Why wasn’t I shown this little girl? Where was she when we were looking for Eleanor? It seemed like Donald had been right all these years. Little Miss 1565 was his sister.

But Marion didn’t want to make a quick decision. She met with another of Eleanor’s aunts, Dorothy, and they looked at the photos together. At first, Dorothy thought the little girl resembled Eleanor. Then she changed her mind.

Marion too, despite her initial reaction, decided it must not be Eleanor after all. Only Donald still thought it was his sister, but he was concerned about the confusion regarding the number of permanent teeth. No one wanted to upset Mildred, so Marion and Dorothy decided to stand by their original decision: Little Miss 1565 was not Eleanor. Officer DeMatteo’s investigation was over.

But that was not the last time Little Miss 1565 would be connected with Eleanor Cook. In 1991, Lieutenant Rick Davey, the same investigator who believed Robert Segee had set the fire, made an announcement that finally gave the people of Hartford a name for the unidentified little girl.

Davey’s interest in the Hartford circus fire had begun in the 1980s. He’d given a talk about the fire at a junior high school and discovered the students knew more than he did about the subject. He promised to return when he knew more.

Davey began his research by looking through old editions of the Hartford Courant and moved on to the extensive archives at the Connecticut State Library. The more he found out about the mystery of Little Miss 1565, the more it haunted him. Davey asked the same questions others had for years: Who was this little girl? Why had no one claimed her? He was determined to figure out her identity.

It was Emily Gill’s letter to Commissioner Hickey that led Davey to suspect that Little Miss 1565 was Eleanor Cook, though Emily had rejected this possibility. He compared the list of the unidentified bodies with the list of missing persons. Two little girls had never been found: Judy Norris and Eleanor Cook. Among the unidentified bodies there were two little girls, 1503 and Little Miss 1565. It stood to reason, Davey thought, that Eleanor Cook was one and Judy Norris was the other.

The paper trail had led Davey to connect 1565 with Eleanor Cook. It was now up to him to address the road blocks that had come up in past investigations. There was little direct forensic evidence to go on, however, and Davey would have to rely heavily on the memory of Donald Cook to answer the questions others had raised. But Davey was persistent. He would make his case.

First, the body of Little Miss 1565 was dressed in a flowered white dress and brown shoes. Marion Parsons claimed that Eleanor did not own clothes like these. According to Davey, Donald told him that Mildred had given the children new clothes during their visit, and they’d been wearing them on the day of the fire.

And what about the difference in height between 1565 and Eleanor? In 1944, Eleanor’s family had said that she was tall for her age, and Little Miss 1565 was only 46 inches tall. That would probably make her the shortest girl in her class. In a conflicting story, Davey claims that Donald had told him Eleanor had a disease called rickets, which would have stunted her growth.

The most useful piece of information Davey located in his search through the archives was the analysis of a hair sample. On July 15, 1944, hair samples from Eleanor were compared to hairs from the body of Little Miss 1565 under a microscope. According to the doctor who compared the samples, “It may be concluded from this examination only that both specimens may have been derived from the same scalp. Absolute identification is, of course, impossible.” What later happened to the hair samples themselves is unknown.

Davey compared morgue photographs of 1565 with a photo of Eleanor Cook. He analyzed the distance between the nose and the upper lip in each photo and found the measurements to be the same. He compared their earlobes (a method used by law enforcement before fingerprinting, though now rarely if ever used) and saw they were also similar. When he looked at the photos of Little Miss 1565, he thought about what fire and extreme heat can do to a body. It shrinks the ears and makes the nose look stubby. If 1565’s ears and nose had not been altered by the fire, Davey thought, she would look more like Eleanor. Little Miss 1565’s hair was mussed and her forehead bulged from being trampled. According to Davey, “Those changes in her appearance would have made it difficult, if not impossible, for her family to recognize the child they knew in life.”

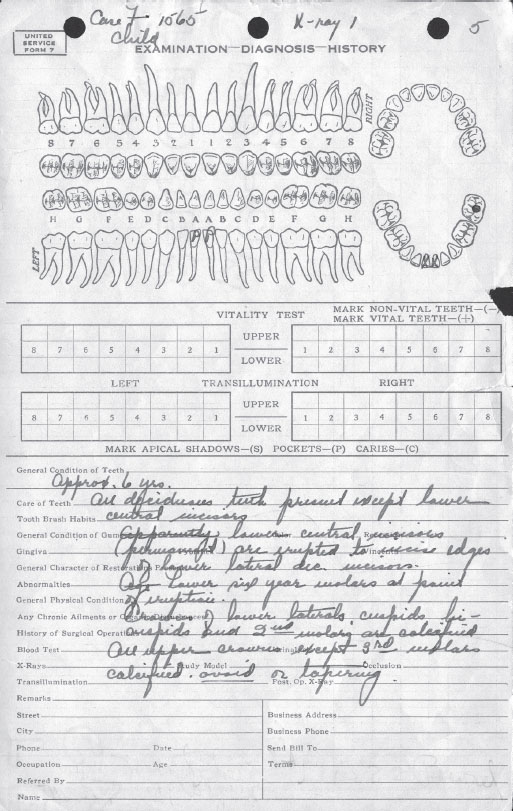

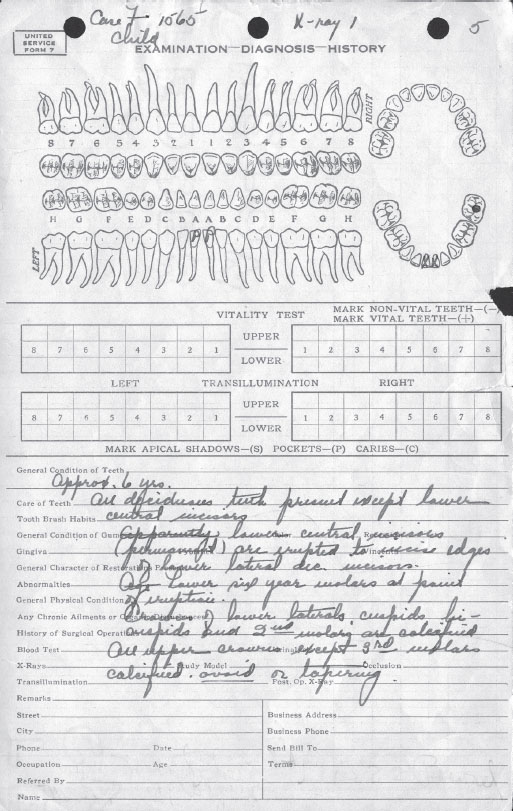

The number one problem in identifying Little Miss 1565 concerned her teeth. Davey looked at the dental chart for 1565. A copy of it was attached to her death certificate in the state library archives. According to the chart, 1565 had only two permanent teeth, incisors on the bottom. However, most eight-year-olds have between 6 and 10 permanent teeth, and Marion Parsons had said Eleanor had 8 permanent teeth. Davey claims the dentist who created the chart was wrong and that 1565 did have eight permanent teeth, making it more likely that 1565 was indeed Eleanor. However, there is no documented forensic evidence to support this claim. At the time of the fire, the family was unable to get Eleanor’s dental records to compare with 1565 because the dentist had been on vacation. When the dentist returned, Little Miss 1565 had been buried, and the Cooks had already held a funeral for Eleanor. The family didn’t pursue it further. Nearly 50 years later, there was no way to make a definitive comparison. According to Davey, the examiner’s chart “seemed rather cursory in its assessments, so [he] did not consider it conclusive.”

Donald had believed for years that Little Miss 1565 was his sister, and Lieutenant Davey was ready to support his claim. In 1991, Davey finalized his conclusions. Donald signed an official document affirming his belief that Little Miss 1565 was his sister Eleanor. Soon after, Davey received a report from Dr. Wayne Carver at the Connecticut medical examiner’s office. After reviewing Davey’s research, Dr. Carver issued a new death certificate, indicating that 1565 was indeed Eleanor Cook.

Dental chart for unidentified victim 1565. The letter P written on the diagram indicates the two permanent teeth.

Elated to have his reward for many years of difficult research, Davey called Donald, and together they drove up to Massachusetts to speak with Mildred, who was now well into her 80s. When Davey told her that he had found her daughter at last, Mildred was happy. A long time had passed since she had lost her children. All her tears had been shed. Mildred did admit to Davey that even after all these years, she had still hoped Eleanor would “appear on the doorstep one day, without warning.”

Months later, the body of Little Miss 1565 was removed from the plot in Northwood Cemetery near Hartford and brought to rest beside Edward Cook in Southampton, Massachusetts. The people of Hartford showed they would never forget the little girl they had looked after for so long. The original marker in Northwood was reinscribed:

RESTED IN PEACE HERE 47 YEARS AS

“LITTLE MISS”

1565

ON MARCH 8, 1991 SHE BECAME KNOWN AS

ELEANOR EMILY COOK,

AND IS NOW BURIED WITH HER FAMILY

The Hartford community has embraced Davey’s conclusion that Little Miss 1565 is Eleanor Cook, but even today not everyone agrees with the outcome of his research. There are questions about his methods and about the lack of direct forensic evidence.

Are there enough similarities between 1565 and Eleanor to make a definitive conclusion? The lack of permanent teeth in 1565 is the most puzzling. It is unlikely that an eight-year-old girl would have only two permanent teeth. To explain this problem, Davey concluded that the dental chart was wrong and that 1565 did have eight permanent teeth. However, it is unlikely that that was the case. In Dr. Weissenborn’s report to the coroner, it is clear that great care was taken to document all possible identifying details. According to the report, the dental chart; X-rays of the skull, teeth, and sinuses; and a picture of the body were sent to the coroner’s office, the state police, and the city police of Hartford. It is true that we do not have Eleanor’s dental records to compare to those of 1565; however, it seems likely that 1565’s dental chart showing only two permanent teeth is correct. If Eleanor had more than two permanent teeth, she cannot be Little Miss 1565. Unfortunately, the X-rays done on 1565, including one showing the teeth, can no longer be found.

Other than the written analysis of the hair samples, which do not provide absolute proof, there is no official forensic evidence that links Little Miss 1565 to Eleanor. The paper trail shows investigators returning to Eleanor again and again, but that does not mean she is the unidentified girl.

Davey assumed that since there were two missing girls and two bodies of little girls, one of them must be Eleanor. In all, there were six unidentified bodies and six missing persons, but, as shown below, their descriptions do not match up.

| MISSING PERSONS | UNIDENTIFIED BODIES |

| Judy Norris, age 6 | 1503, female, 9 years old |

| Eleanor Cook, age 8 | 1565, female, 6 years old |

| Edith Budrick, age 38 | 4512, female, 35 years old |

| Raymond Erickson, age 6 | 1510, male, 11 years old |

| Grace Fifield, age 47 | 2109, female, 30 years old |

| Lucille Woodward, age 55 | 2200, male, 55 years old |

No one reported an adult male missing, but there’s an unidentified male body. Three adult females were reported missing, but there are only two adult female bodies. When the medical examiner assessed the age and sex of the unidentified bodies, the remains—other than those of 1565—were almost unrecognizable.

Stewart O’Nan, a researcher and author on the subject of the circus fire, offers another striking possibility. Maybe neither of the unidentified girls is Eleanor. Twenty of the victims had been girls between the ages of six and nine years old. O’Nan says, “One mistake at the armory would throw the whole chain into chaos.” Many of the bodies were difficult to identify, and families were understandably distressed. Is it possible that someone brought home the body of Eleanor and left their little girl behind? Could Eleanor have been buried in the plot of one of the other 19 little girls around her age?

Without forensic evidence, can we be sure that 1565 is indeed Eleanor Cook? In 1944, little was known about DNA; tests investigators use today to identify people had not yet been developed. Had DNA testing been available, it could have proven without a doubt whether 1565 was Eleanor by comparing her DNA with that of her brother. In 1991, when the body of Little Miss 1565 was moved to Southampton, no forensic evidence was collected. O’Nan claims that Donald had offered to give a DNA sample for confirmation, but no test was ever done.

Despite the many questions raised, Rick Davey and Don Massey, coauthors of a book describing Davey’s investigations, are unwavering in their conclusion about Little Miss 1565. “There is no doubt in our minds who she is,” Massey said to an audience in Hartford, Connecticut, in July 2010.

It is easy to see why so many people are facinated by the mystery of Little Miss 1565. Conflicting stories among Eleanor’s family and decades of investigation seem to have led to more questions than answers. Is Little Miss 1565 Eleanor Cook? We may never know for sure.

We do know one thing: on a sunny July day, Eleanor Cook went to the circus with her family, but she, along with the 166 other victims of the Hartford circus fire, never came home. The community of Hartford mourned this tragedy as if each person who died was a member of the family. As the years go on, and the disaster has faded from the national newspapers, the people of Hartford still remember. Every July 6 the Hartford fire department holds a memorial service on the site where the big top tent once stood. Survivors and others gather each year so that the men, women, and children who were lost will live on in our memories.