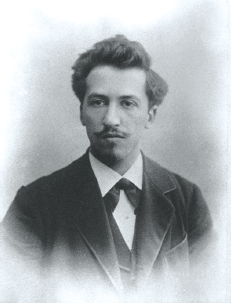

Perhaps the most radical reductionist of the early abstract artists was the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, the first artist to create an image from pure lines and color. Mondrian entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam in 1892, at age twenty. The very next year he held his first exhibition. Mondrian later moved to Paris, but he left in 1938 and, after a brief stay in London, moved to New York in 1940. There he met the artists of the New York School.

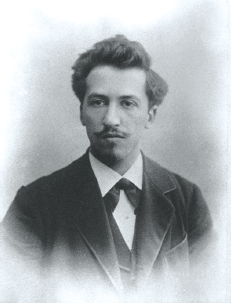

Like J.M.W. Turner, Arnold Schoenberg, and Wassily Kandinsky, Mondrian (

fig. 6.1) began as a figurative painter. Influenced by Vincent van Gogh, Holland’s most famous modern painter, Mondrian painted landscapes, farms, and windmills. His skill is evident in superb early paintings such as

Windmill in the Gein, painted in 1907, and

Woods Near Oele, painted in 1908 (

figs. 6.2,

6.3).

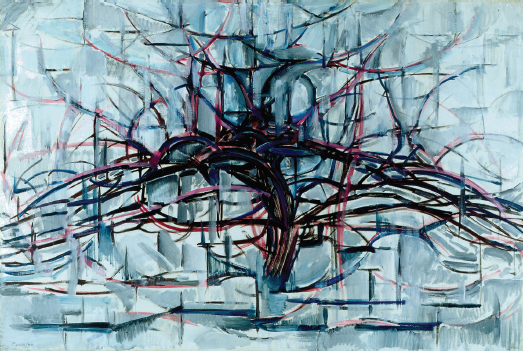

In 1911, after seeing an exhibition of Cubist works by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in Amsterdam, Mondrian moved to Paris. There, he began painting in an analytic Cubist style (Blotkamp 1944). Like Picasso and Braque, Mondrian explored the influential ideas of Paul Cézanne, who greatly influenced the analytic Cubists with his idea that all natural forms can be reduced to three figural primitives: the cube, the cone, and the sphere (Loran 2006; Kandel 2014). Mondrian recognized the plastic elements in analytic Cubism, and he began to echo the Cubists’ use of geometric shapes and interlocking planes. He reduced a specific object, such as a tree, to a few lines and then connected those lines to the surrounding space (

fig. 6.4), thus entangling the branches of the tree with its surroundings. Yet whereas Cubist works played with simple shapes in a complex arena of shattered space, Mondrian’s art became more reductionist. He distilled figures to their most elemental forms, eliminating altogether the sense of perspective.

6.1 Piet Mondrian (1872–1944)

6.2 Piet Mondrian, Oostzijdse Mill with Panoramic Sunset and Brightly Reflected Colors, 1907-08, Oil on canvas, 99 x 120 cm (39 x 47 1/4″)

6.3 Piet Mondrian, Bosch (woods): Woods Near Oele, 1908, Oil on canvas, 128 x 158 cm (50 3/8 x 62 1/8″)

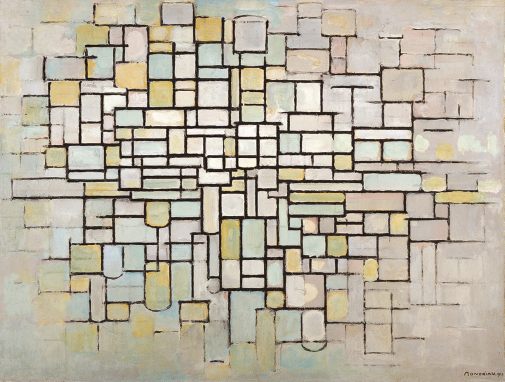

In his search for universal aspects of form, Mondrian developed completely nonrepresentational pictures composed of straight lines and minimal color (

fig. 6.5). In this way he succeeded in systematically developing a new language of art based on simple geometric forms that have a meaning of their own, without reference to specific forms in nature. Paradoxically, Mondrian used this reductionist approach to preserve what he considered to be the essence of the mystical energy that governs nature and the universe. In constructing his perception of the essence of an image and freeing it from content, he enables the viewer to construct his or her own perception of the image.

6.4 Piet Mondrian, Tree, 1912, Oil on Canvas, 75 x 111.5 cm (29 1/2 x 43 7/8″)

In 1959, brain scientists discovered an important biological basis for Mondrian’s reductionist language. David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, working first at Johns Hopkins University and then at Harvard, discovered that each nerve cell in the primary visual cortex of the brain responds to simple lines and edges with a specific orientation, whether vertical, horizontal, or oblique (

fig. 6.6). These lines are the building blocks of form and contour. Eventually, higher regions of the brain assemble these edges and angles into geometric shapes, which in turn become representations of images in the brain.

6.5 Piet Mondrian, Composition No. II Line and Color, 1913, Oil on Canvas, 88 x 115 cm (34 3/4 x 45 1/4″)

Zeki describes these physiological findings:

In a sense, our quest and conclusions [are] not unlike those of Mondrian and others. Mondrian thought that the universal form, the constituent of all other, more complex forms, is the straight line; physiologists think that cells that respond specifically to what some artists at least consider to be the universal form are the very ones that constitute the building blocks which allow the nervous system to represent more complex forms. I find it difficult to believe that the relationship between the physiology of the visual cortex and the creations of artists is entirely fortuitous. (Zeki 1999,

Inner Vision 113)

6.6 Neurons in the primary visual cortex respond selectively to line segments that correspond to the specific orientation of their receptive fields. This cell responds most vigorously to a diagonal segment that runs from 10 to 4 o’clock (dashed outline). This selectivity is the first step in the brain’s analysis of an object’s form.

The discovery by Hubel and Wiesel of cells that respond to linear stimuli with specific axes of orientation may partly explain our response to Mondrian’s work, but it does not explain the artist’s focus on horizontal and vertical lines to the exclusion of oblique lines. Vertical and horizontal lines represented for Mondrian the two opposing life forces: the positive and the negative, the dynamic and the static, the masculine and the feminine. This reductionist vision is reflected in the evolution of his work. Perhaps Mondrian also implicitly realized that by excluding certain angles and focusing only on others he might pique the beholder’s curiosity and imagination about the omissions.

As Charles Gilbert of Rockefeller University has pointed out (personal communication, 2012), it is likely that Mondrian’s linear paintings recruit intermediate-level visual processing, which takes place in the primary visual cortex. As we have seen, intermediate-level processing analyzes the shape of objects by determining which surfaces and boundaries belong to them and which belong to the background—the first step in generating a unified visual field (Gilbert 2013a). Mondrian’s paintings are also subject to top-down processing, in which we bring to bear on them our experience with other art and other artists.

Lines play a prominent role in the work of many modern artists who followed Mondrian, including Fred Sandback, Barnett Newman, and, to a lesser extent, Ellsworth Kelly and Ad Reinhardt. This emphasis on line does not, in all likelihood, derive from the artists’ interest in or knowledge of geometry. Rather, it stems from their efforts, following Cézanne, to reduce the complex forms of the visual world to their essentials and to infer, as the Renaissance artists did with perspective, the essence of form and the rules our brain uses to prescribe form.

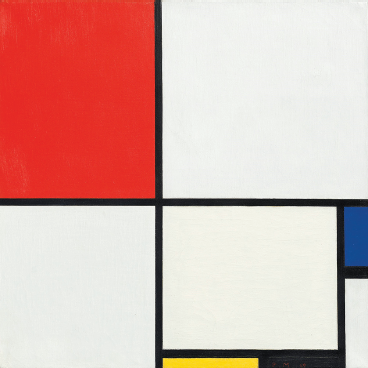

In his later work, from the end of the 1920s to his death in 1944, Mondrian applied the same radical reductionist treatment to color. He reduced his palette to the three primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—on a white canvas divided by black vertical and horizontal lines (

figs. 6.7,

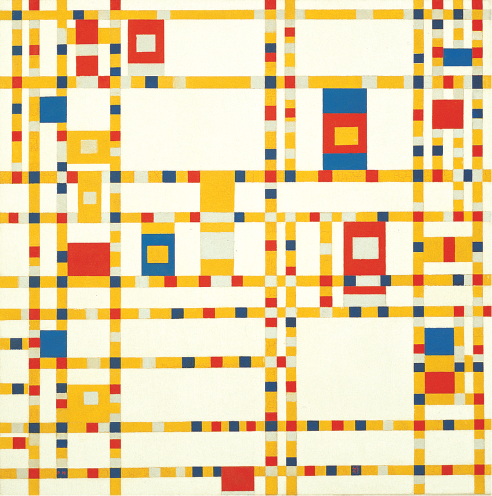

6.8). In these late paintings, the artist’s reduction of form and color creates a sense of movement. This is perhaps most evident in

Broadway Boogie Woogie (

fig. 6.8). Looking at this painting, we can almost feel the boogie woogie beat; our eyes are forced to move around the canvas from one red, blue, or yellow color block to another. As Roberta Smith has pointed out (2015), the pulsating quality of Mondrian’s color painting—its totality—presages the constant sense of surprise and movement we encounter in Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings.

6.7 Piet Mondrian, Composition No. III, with Red, Blue, Yellow, and Black, 1929 Oil on canvas, 50 x 50.5 cm (19 5/8 x 19 7/8″)

Although he continued periodically to paint figurative works, Mondrian felt that using basic forms and colors enabled him to express his ideal of the universal harmony inherent in all of the arts. He believed that his spiritual vision of modern art would transcend divisions in culture and become a common international language based on pure primary colors, flatness of form, and the dynamic tension in his canvas.

By the early 1920s Mondrian had fused his art and his spiritual interests into a theory (published as “Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art”) that signaled a complete break with representational painting. His description of his work could serve as a general manifesto for reductionist approaches in art:

I construct lines and color combinations on a flat surface, in order to express general beauty with the utmost awareness. Nature (or, that which I see) inspires me, puts me, as with any painter, in an emotional state so that an urge comes about to make something, but I want to come as close as possible to the truth and abstract everything from that, until I reach the foundation (still just an external foundation!) of things. (Mondrian 1914)

6.8 Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-1943 Oil on canvas, 127 x 127 cm (50 x 50″)