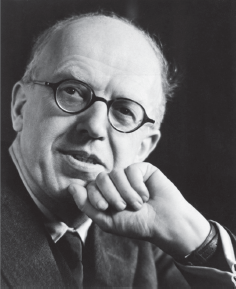

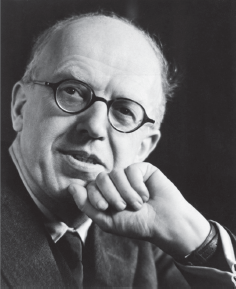

In 1959 C. P. Snow, the molecular physicist who later became a novelist (

fig. i.1), declared that Western intellectual life is divided into two cultures: that of the sciences, which are concerned with the physical nature of the universe, and that of the humanities—literature and art—which are concerned with the nature of human experience. Having lived in and experienced both cultures, Snow concluded that this divide came about because neither understood the other’s methodologies or goals. To advance human knowledge and to benefit human society, he argued, scientists and humanists must find ways to bridge the chasm between their two cultures. Snow’s observations, which he delivered in the prestigious Robert Rede Lecture at the University of Cambridge, have since spurred considerable debate over how this could be done (see Snow 1963; Brockman 1995).

1

My purpose in this book is to highlight one way of closing the chasm by focusing on a common point at which the two cultures can meet and influence each other—in modern brain science and in modern art. Both brain science and abstract art address, in direct and compelling fashion, questions and goals that are central to humanistic thought. In this pursuit they share, to a surprising degree, common methodologies.

While the humanistic concerns of artists are well known, I illustrate that brain science also seeks to answer the deepest problems of human existence, using as an example the study of learning and memory. Memory provides the foundation for our understanding of the world and for our sense of personal identity; we are who we are as individuals in large part because of what we learn and what we remember. Understanding the cellular and molecular basis of memory is a step toward understanding the nature of the self. In addition, studies of learning and memory reveal that our brain has evolved highly specialized mechanisms for learning, for remembering what we have learned, and for drawing on those memories—our experience—as we interact with the world. Those same mechanisms are key to our response to a work of art.

i.1 C. P. Snow (1905–1980)

Whereas the artistic process is often portrayed as the pure expression of human imagination, I show that abstract artists often achieve their goals by employing methodologies similar to those used by scientists. The Abstract Expressionists of the New York School of the 1940s and 1950s provide an example of a group that probed the limits of visual experience and extended the very definition of visual art. (For earlier attempts to bridge the two cultures, see E.O. Wilson 1977; Shlain 1993; Brockman 1995; Ramachandran 2011.)

Until the twentieth century, Western art had traditionally portrayed the world in a three-dimensional perspective, using recognizable images in a familiar way. Abstract art broke with that tradition to show us the world in a completely unfamiliar way, exploring the relationship of shapes, spaces, and colors to one another. This new way of representing the world profoundly challenged our expectations of art.

To accomplish their goal, the painters of the New York School often took an investigative, experimental approach to their work. They explored the nature of visual representation by reducing images to their essential elements of form, line, color, or light. I examine the similarities between their approach and the reductionism that scientists use by focusing on these artists as they move from figurative to abstract art—in particular, the work of the early reductionist painter Piet Mondrian and the New York painters Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Morris Louis.

Reductionism, taken from the Latin word reducere, “to lead back,” does not necessarily imply analysis on a more limited scale. Scientific reductionism often seeks to explain a complex phenomenon by examining one of its components on a more elementary, mechanistic level. Understanding discrete levels of meaning then paves the way for exploration of broader questions—how these levels are organized and integrated to orchestrate a higher function. Thus scientific reductionism can be applied to the perception of a single line, a complex scene, or a work of art that evokes powerful feelings. It might be able to explain how a few expert brushstrokes can create a portrait of an individual that is far more compelling than a person in the flesh, or why a particular combination of colors can evoke a sense of serenity, anxiety, or exaltation.

Artists often use reductionism to serve a different purpose. By reducing figuration, artists enable us to perceive an essential component of a work in isolation, be it form, line, color, or light. The isolated component stimulates aspects of our imagination in ways that a complex image might not. We perceive unexpected relationships in the work, as well as, perhaps, new connections between art and our perception of the world and new connections between the work of art and our life experiences as recalled in memory. A reductionist approach even has the capacity to bring forth in the beholder a spiritual response to the art.

My central premise is that although the reductionist approaches of scientists and artists are not identical in their aims—scientists use reductionism to solve a complex problem and artists use it to elicit a new perceptual and emotional response in the beholder—they are analogous. For example, as I discuss in

chapter 5, early in his career J.M.W. Turner painted a struggle at sea between a ship heading for a distant harbor and the natural elements: the storm clouds and rain bearing down on the ship. Years later, Turner recast this struggle, reducing the ship and the storm to their most elemental forms. His approach allowed the viewer’s creativity to fill in details, thereby conveying even more powerfully the contest between the rolling ship and the forces of nature. Thus, while Turner explores the boundaries of our visual perception, he does so to engage us more fully with his art, not to explain the mechanisms underlying visual perception.

Reductionism is not the only fruitful approach to biology, or even to brain science. Important, often critical insights are gained by combining approaches, as is evident in the advances made in brain science through computational and theoretical analysis. Indeed, a major step forward in the study of the brain was the scientific synthesis that occurred in the 1970s, when psychology, the science of mind, merged with neuroscience, the science of the brain. The result of this unification was a new, biological science of mind that enables scientists to address a range of questions about ourselves: How do we perceive, learn, and remember? What is the nature of emotion, empathy, and consciousness? This new science of mind promises not only a deeper understanding of what makes us who we are but also to make possible meaningful dialogues between brain science and other areas of knowledge, such as art.

Science attempts to move us toward greater objectivity, a more accurate description of the nature of things. By examining the perception of art as an interpretation of sensory experience, scientific analysis can, in principle, describe how the brain perceives and responds to a work of art, and give us insights into how this experience transcends our everyday perception of the world around us. The new, biological science of mind aspires to a deeper understanding of ourselves by creating a bridge from brain science to art, as well as to other areas of knowledge. If successful, this endeavor will help us understand better how we respond to, and perhaps even create, works of art.

Some scholars are concerned that focusing on reductionist approaches used by artists will diminish our fascination with art and trivialize our perception of its deeper truths. I argue to the contrary: appreciating the reductionist methods used by artists in no way diminishes the richness or complexity of our response to art. In fact, the artists I consider in this book have used just such an approach to explore and illuminate the foundations of artistic creation.

As Henri Matisse observed: “We are closer to attaining cheerful serenity by simplifying thoughts and figures. Simplifying the idea to achieve an expression of joy. That is our only deed.”