14

The Visit

With her chin lifted and my arm through hers, Mama stopped at the exit to the gate. “You can let go now. I’m going out on my own. But please stay right behind me.”

Glancing over her four-foot-eight frame as we stepped into the building, I spotted Dorothy watching our door. Most people had already left the area, so she was nearly alone. Mama had asked that nobody else come to the airport except Dorothy and her husband, so she wouldn’t be overwhelmed.

Dorothy was dressed in just-plain-folks’ polyester slacks and a wide cut overblouse. I couldn’t tell if it was her intense eyes or her girth that made her seem so much taller than her five feet, one inch. Maybe my nerves were making her bigger.

She swayed forward slightly onto her toes, watching Mama emerge, examining her sister like a true believer in a divine moment. Then Dorothy rocked back, regained her balance, and started slowly toward Mama.

Mama walked too, straight to Dorothy, and I fell back to watch. Neither spoke. With unblinking eyes, they advanced toward each other in slow old lady steps. When they got toe-to-toe, trembling and mute, the sisters leaned in, their foreheads resting together like brain-conjoined twins. As they wrapped their arms around each other, foreheads glued, Dorothy said, “I love you.” They looked out of the tops of their eyes at each other, their contented faces awash in tears.

Hardly able to collect herself, Mama mumbled, “I’ve missed you . . . terribly . . . all these years, Dot.” She sucked in a deep enough breath to say, “I’m . . . so sorry. I love you. Do you forgive me?”

“Shush now, Ella. You’re home. Don’t worry about being forgiven anymore.” Dorothy stepped back a bit and gave Mama a gossamer sweet kiss on her lips. They lingered a moment, their eyes closed as if in a first kiss. When they moved back, the two wrinkled women’s eyes shone, a flush of color risen in their cheeks.

Mama stretched her hand out for me to come. She stood steady then, the take-my-medicine worry on her face replaced with wonderment. Dorothy turned to me with a soft smile and I smiled back. Would she hug me too, Mama’s black daughter? Or was I just the escort to bring my mother to her? Mama took my hand. Then Dorothy reached over and took the other, squeezing it hard.

“I never thought I’d see my sister again,” she said. “How can I ever thank you?”

“You’re welcome,” I said, squeezing her hand back. She put her arms around me, and we hugged too.

Dorothy introduced Mama to Tony, who’d waited, motionless and watchful, all this time. As he came forward, his keen eyes smiled. “I’m glad to know you, Ella. You and Dolores are welcome here. All right now, let’s go on home.” He was a man on task, the one in charge of this flock. He’d perfected the role raising four daughters and being the only male in the house.

The two sisters, one thin and one stout, were lost in talk as they ambled through the corridors, oblivious to newsstands and eateries on their way to baggage claim. Tony and I followed, making small talk about the trip and watching them.

“We’ve been pretty nervous about coming out here,” I said in my gentlest voice.

“I know, so have we. But lookit them two,” he said, fetching our suitcases off the moving belt. “Now, I just bet they’re going to try to talk about every single thing that happened the last thirty-six years in this one week. I think Dot’s planning on it.”

Tony guided us out to the curb and into the car. While Dorothy talked a mile a minute from the front seat, Mama watched along the route for the buildings and areas she recognized. Dorothy narrated all the changes in town from decades gone by as Mama leaned forward and talked to her through the gap by their doors.

We wound down a thoroughfare, passing the midsized downtown of an urban Indianapolis being revitalized from the impact of rust belt decline and the apparent white flight. Dorothy pointed out all the buildings the city fathers had put up in recent years. Mama craned her neck to see the new convention center, and the I-65 highway that led to their old neighborhood. That was the road that caused their old home to be torn down. We headed out of the city into an area where houses sat on lawns and land, finally arriving in Dorothy’s town of Greenwood. That semirural suburb of houses was nothing like the sardine-lot, fifty-year-old houses in the city where we’d lived. Mama, ever the gardener, admired the beds of blue hydrangeas and red geraniums while everyone avoided the scorched earth of her thirty-six years in hiding.

I wasn’t looking for flowers. I was looking for people of color. But there wasn’t a one, anywhere. Not just no blacks, but no Hispanics, Asians, or Native Americans. It was a world tilted out of balance, skewed to all white. Was that the way the Boehles wanted it? Were they way out here to get away from minorities, like our neighbors in Cold Spring did when we moved onto Florida Street?

In their newish ranch house, we entered an airy living room that opened to a veranda overlooking a patch of green farmland. The homemade quilted decorations and jars of vegetables put up in mason jars announced a midwestern life I’d only read about. Like our old house, they had three tidy bedrooms, including a twin-bedded guest room where we’d sleep. And they had a second bathroom, something Mama never had.

We women went out on the canopied veranda for lemonade. Tony changed into overalls to work the fields with the John Deere equipment sitting out there. I asked him if you’d call his place a farm. Not like it used to be, Tony told me, when he and his brothers kept cows, chickens, and crops enough to feed their families.

“I don’t know a thing about farming,” I said. “Did your girls work outside too?”

“Naw, they mostly helped their ma put the food up. Except the time Antoinette, our oldest, had to deliver a calf all by herself.” She was the only one home when the cow began bellowing, so his daughter stuck her arm inside the cow, all the way up to her shoulder to ease the calf out.

“Antoinette had blood ever’where, all over herself,” Tony said. “But we were sure proud of her, being a teenager and all.” The cow and calf came through fine.

Urban creature that I was, I couldn’t imagine doing any such thing. The closest I’d ever gotten to an animal was feeding lettuce leaves to our pet rabbits who lived in the back hall coal bin that supplied our potbellied stove. This life the Boehles had was more Little House on the Prairie than any place I’d lived. New York, DC, and Boston were crowded, multicultural centers of rushing people whose farm contact was limited to a cellophane tray in a grocery store.

The Boehles talked with an everyman speech, stripped of the code switching I used every day in New Jersey to survive. I had the unfiltered street slang, the self-protective black posturing that fended off haters, and the white corporate speak expected in professional settings. Mama warned me not to bring the latter home to the ghetto because it sounded like showing off. If I wanted to make a connection with my Indiana family, I had to drop all those voices and just speak plainly. From the heart, like Luther told me.

As Dorothy prepared dinner I looked at her photos on the walls and tables. Each of their four daughters’ wedding photos sat out, in Catholic churches or receptions, perhaps in the parish hall. Some of the cute grandchildren pictured were blonde or blue-eyed. And every one of them in this family gallery was, of course, white, something I’d never seen. Mama followed; her awe evident at the first sight of the family love that her sister said would be ours.

Dorothy reached for another picture, a special one she’d laid out. “This is for you to keep, Ella.”

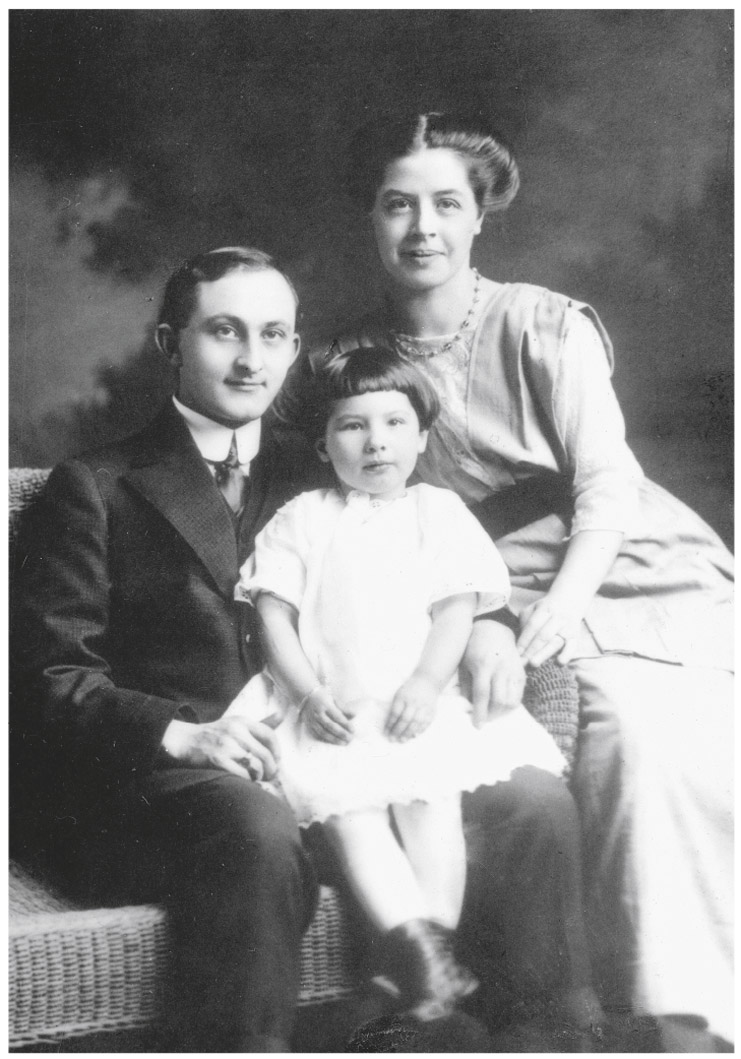

“Here are your grandparents,” she told me. “This is your blood grandmother. Your mother’s mother. You know we’re half sisters because we had different mothers, right? Look Ella, you were a little thing.” We peered at the five-by-seven black-and-white, laminated over the frame.

“I’d just about forgotten my mother’s face,” Mama said, holding the frame reverently. “After she died, I used to look at the moon and see her face watching over me. But then after a while I couldn’t remember how she looked. What a treasure, Dot.”

My mother was maybe four, with a bowl cut and a fancy dress that covered her knees. She sat between her father in his vested suit and her mother in a long, high-necked dress, around 1913, Mama guessed. I searched Henry and Florence Lewis’s features for clues as to who I was. He seemed tall, though he was seated, had dark hair combed straight back, and a pronounced nose unlike any of ours. My grandmother’s delicate skin was offset with deeply waved hair braided and curled into balls behind either ear. I tried to feel them, to be a part of them. But nothing connected. Not until my grandmother’s eyes drew me in. She looked directly into the camera, full of strength. Her look was like my mother’s and my eyes in our own high school portraits. And I knew it, this white grandmother was a part of me.

We ate baked chicken seated in kitchen chairs that swiveled and filled in get-acquainted stories as twilight neared. At the end of the meal Dorothy turned sober. “We’re just sorry your Charles couldn’t come out this trip. You know he was welcome, too.” I wondered if she would really welcome the black man who took her sister away.

“Well,” Mama said. “He wanted us to have time alone first, but he’s looking forward to seeing you another time.” She must have rehearsed that. I felt badly for Mama, because I knew she’d sanitize her secret—that the man she gave up her family for had been an alcoholic for much of their marriage. He’d functioned for the most part, working every day, and drinking only at home. But still, here was my mother hiding it from her sister with the familiar charade we played outside the family. Mama had been clear she didn’t want me to say anything about it.

My mother, Ella, with her birth parents, Henry and Florence Lewis, circa 1913.

We were polishing off our chicken when Mama cleared her throat. “Uh, tonight while it’s just us, can we talk about when I left back in ’43? Pick up the pieces?” She wiped her mouth with the napkin, twice.

“All right, I’m glad you want to,” Dorothy said. “I do too.”

This is why we came. If Dorothy had any long-brewed bitterness toward Mama or racist remarks about Daddy and me, it would come out now. A pain jammed my mostly dormant old stomach ulcer, and Tony’s eyes focused on Mama. Dorothy cleared the plates and set a box of Kleenex in the middle of the table, where the salt and pepper sat.

“Dot, can you understand that Charles and I were scared to death to stay here in Indianapolis?” Mama started. “People were so prejudiced, we were bound to get hurt. I wanted to get married and have a family like everybody else. But who here was going to marry me after I divorced Alan?”

“Charles gave you a family, but,” Dorothy opened out both palms, “why didn’t you talk to Dad before you left? He might’ve understood, Ella.”

“But not Mother. You know she wouldn’t have it. Remember how she refused to let Tony, my first boyfriend, in the house because he drank beer and drove too fast?”

“I surely do,” Dorothy said. She told us he’d found the perfect job for his wild streak, in a pit crew at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. A natural fit for the boy riding Mama on the back of his motorcycle, outpacing cops who chased them down alleys. Dorothy said Mama was some hot ticket in her day, sneaking out on dates and waking her up when she climbed over Dot and into bed late.

One look at the expression on my face and Mama started laughing. “You talk about fun! We used to slip out and go hot-rodding around in his roadster too. A 1929 cream-colored dream! I even rode on the hood one time, posing like Miss America on a float. But we hit a bump and I fell forward off the car. It was lucky I fell between the tires, because he couldn’t stop in time. The wheels rolled right past me on both sides.”

Dorothy got up and went to her bedroom to get a newspaper obituary. Mama chuckled as she read how Tony became a riding mechanic and a crewman at the speedway, with his picture hanging on their wall of fame. “And Mother said he wouldn’t amount to anything,” Mama said, as she and Dorothy giggled like teenagers.

No wonder Mama married a black man in Klan country. She was a rebel all along.