17

Shift

Aunt Dorothy’s fifteen-page letters, cards, and calls started right away. They were the communiques that helped us grow closer despite the distance. And most important, there were some short, cordial conversations between Dorothy and Daddy, as I remember. Theirs was the one essentially healing connection that would help us understand some of the trickiest parts of our relationship. But the opportunity to put Daddy and the Boehles together was forever lost when Daddy died a few months after Mama went back to Indy, before the Boehles could ever meet him.

While Daddy lay in a coma for weeks, everyone came to the hospital except David. When I tracked him down at a friend’s house to go to the hospital with me, David choked up.

“I can’t stand to see him wired up to everything but the kitchen radio,” he said. No, he wouldn’t look at the respirator pumping air through a tracheotomy cut in Daddy’s throat. No, he couldn’t bear to relieve Daddy’s scabbed tongue with a glycerin swab. Not his father who’d become his drinking buddy, the father he did the Amos ’n’ Andy routine with, the father who came to David’s sixth-grade classroom every year with a stalk of sugarcane and a ball of cotton to tell the inner-city have-nots about farming down south. In adulthood, David was more like Daddy and much closer to him than Charles Nathan and I. At the graveside, he was the one who broke down, holding the wide-brimmed white hat he bought over his eyes but unable to hide his sobbing behind it.

The rest of us had had far more complicated feelings about Daddy for a long time. Mama, married to him for thirty-seven years, looked lost, and Charles let out a yelp of what?—anguish, guilt, or love?—over the casket. But even as I mourned him, I still had not come to terms with all the damage his Four Roses whiskey in that pink plastic cup had caused among us. As a teen, I’d childishly tried to stop the drinking by pouring his bottles down the drain. Of course, he had other bottles hidden and a liquor store two blocks away, so his hair-trigger rages continued to turn our home inside out. Before going away to college, I resorted to staying in my room to avoid interactions when my brothers were out and Mama was at work. And as an adult, I only tolerated him.

Yet Daddy handled his business. He was a faithful husband and father who came home every night to preside over dinner. He guided, disciplined, and entertained us kids. He was a solid provider who for decades took three busses across town in Buffalo blizzards to get to his welding job.

Mama did her duty as wife and mother while wringing her hands and urging Daddy to calm down for nearly forty years. Pleading for Daddy to stop raging at all of us, pleading for him to stop hitting us with that welding shop strap with buckles on the ends.

But we were all clear on our unspoken pact—to keep up appearances and keep outsiders in the dark about what went on at home.

In the week after his funeral, Mama and I pulled up in front of a takeout to get some dinner. She put her hand on my forearm, to stop me getting out.

“You had such a hard time with your father,” she said.

“What tore me up was what his drinking did to our family.”

“You’re not the only one,” she said. “I disliked Daddy’s drinking as much as you. But I was married ‘for better or worse,’ and did my best even when times were at their worst.”

We sat in that hot car in front of the pizza shop, finally confessing our shared misery of living with an alcoholic. Like the canceled plans and cover-up excuses when Daddy was in no shape to go out with Mama. Or the Thanksgiving dinner when he drunkenly passed out in his stuffing and gravy in front of company. Or on Charles Nathan’s graduation night when he tried to knock his son out for signing up to join the army. What we didn’t know then, but I learned years later in an Adult Children of Alcoholics meeting, was that Daddy’s kind of chaos went on in many families and impacted everyone in them. But none of us ever knew to get help.

This was the secret Mama wanted buried with Daddy. It was for this reason she did not call her newfound and loving sister Dorothy to come for her husband’s funeral. We all agreed it made no sense to arrange Dorothy’s first visit with black people while we were being gutted. Nevertheless, Dorothy showered Mama with flowers, letters, and calls of concern in the months that followed, loving her as only a sister could.

Meanwhile, we Jacksons burrowed in together, to dredge up and weigh the racist assaults that drove Daddy to drink. And as he finally rested in peace, we privately acknowledged that liquor was the only escape he found while defending his white wife, his mixed children, and his own black body during a lifetime when America thought we were an abomination.

Mama and Daddy’s twenty-fifth anniversary, 1968.

Later that summer, Mama and Dorothy wanted to see each other again and insisted I had to be a part of their plans. They both came to visit Luther and me in New Jersey, which became their pattern for the next twenty-six years, to vacation together, usually with me. It was broiling hot the week they had their second visit. We wandered a mall worshipping its air-conditioning, then went home at closing time. The house was still intolerably stifling.

With the only air conditioner in our master bedroom, Luther dragged in twin mattresses from the guest room where Mama and Dorothy were staying. Dressed in our thinnest clothes, the elders climbed into our queen bed while Luther and I lay on the floor mattresses. As that old air conditioner, set on blast, chugged on noisily, our German shepherd whined outside the bedroom door.

“He’s hot too,” Mama said, getting up to let him in. He plopped down near our feet, in the line of cool air.

“Good night, Mama,” Luther said.

“Good night, Dorothy,” Mama said.

“Good night, Luther,” I said.

“Good night, Dolores,” Dorothy said.

“Good night, Baron,” Luther said.

“Good night, John Boy,” Aunt Dorothy said, laughing at The Waltons show sign off.

During that visit, I got out the genealogy chart that had triggered my search for Dorothy, hoping we could flesh out more of Mama’s family history beyond her parents. Could they trace the line back to my European who came to the States, the equivalent white root to the African Aunt Willie told me about? Finding my African had anchored the family line that was lost when slavers severed those ties. Maybe with a similar white anchor I could also understand the essence of the whiteness in me. There had to be more beyond the current day Boehles and my grandparents Lewis.

Over several days, the sisters set about piecing stories together through fuzzy memories and family lore. It took a lot of sorting and backtracking through the folks best remembered before they decided my family was French and Scotch.

We crafted another genealogy tree. But once it was laid out on paper, we saw Mama was wrong. She was talking about her adoptive grandparents’ heritage, not her birth mother Florence’s bloodline. In fact, she didn’t know anything about Florence’s background, except she was nicknamed Ella after her own mother Ella, and both those women had died young. When Florence’s mother died, her father (whose background Mama didn’t know either) arranged Florence’s adoption by George Scott, a paper hanger who immigrated from Scotland, and his wife, Ella Amanda, who had French heritage.

But they were not my bloodline. My only palpable connection on Mama’s side was all those Ellas, who gave me my own never-used first name—Ella.

On my grandfather Henry Marshall Lewis’s side, both his father, Charles Lewis, and his mother, Minnie Knowlton, were born in Ohio. Where their elders came from was unknown, but the names had origins in Britain, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Minnie was a member of the Marshall drugstores family, and her dad was a banker.

The story Dorothy and Mama told me about their father’s family amounted to this. Minnie died young, and Charles Lewis remarried. He and his second wife, who had more children, had already cut Henry off because he decided to marry Florence, who they thought beneath their station. During summers when Mama was a girl, she went back to Ohio to visit her plain-living grandparents, the Scotts. They would dress her in her best for the occasional dinners she was invited to at grandfather Charles’s big three-story house, with the music room, grand circular stairway, and her three aunts and uncles. While once wealthy, the Lewises apparently lived beyond their means for so long they later had to convert second-floor bedrooms into accommodations for four boarders. But they held on to their symbols of better days, and still set the table with china, linens, and the crystal napkin ring that Dorothy pinched the only time Henry’s second family was invited to their house. Fifty years later, Dorothy gave that napkin ring to Mama. Now it sits in my dining room hutch, my only other connection to those white forebearers.

I’d only found two generations back on my white side, with some probability of bloodlines near Britain, but had not found my European root. What I did find was that my discovered whiteness, adopted and related, was so much more privileged and freer than I or my black family began with. My maternal grandmother was raised by a striving craftsman who chose to immigrate to America for a better life, plying his trade freely in the late 1800s while my black sharecropper grandmother was being raped by a plantation white man. My paternal grandfather Lewis was a self-made electrician hired to help wire up the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and his grandfather was a banker born in 1852, when my black people were slaves. My grandfather Henry grew up in a fancy home where his parents’ status made them think they could look down on other whites while my black father feared Klan violence by all classes of whites. Yet the kind of opportunity privilege my white people had didn’t flow to me through my mother. She gave it all up for the love of a black man, and I was raised never knowing what that meant.

But Mama did pass down a certain whiteness to me—her knowledge of what was on the other side of the color line. However incidental to her practical mothering, she gave me her own Standard English and white social manners. She used the entitled sense that one could and should ask for what was important from those who could change things (like getting my fellowship funds transferred to Harvard), something many blacks were reluctant to do. She lived the assumed right to be unapologetic for who you are despite other’s opinions (even as blacks tried to hide their ways to accommodate white’s expectations, like I did when shape-shifting). Mama gave me insight into the white Catholicism that helped me understand the Boston jobs and political landscape dominated by Irish Catholics while I lived there. And she gave me the understanding that white people could have the decency and respect for other races that she and her sister shared.

Not until I wrote this book did I understand what my half-black, half-white, mixed race meant. My early struggle to rise to my full potential as the black person I knew myself to be was advantaged by my insider’s notion of how some whiteness functions in America. That unique mix of determination and insight was its own form of privilege.

At seventy years of age, I picked up the hunt to find more about my makeup by spitting into an AncestryDNA kit. Yet when the test results showed my heritage was 75 percent British Isles and northwestern Europe, I went into orbit. How could I be that much more white than Mama’s 50 percent donation? It had to be that old Georgia plantation rapist’s blood I never wanted to claim that ran through me still. So, my black half, the half that defined most of my life, is only a quarter of my biology.

American society said I was Negro at birth, and I was raised to understand myself as black. It was not only Mama’s white blood that counted for nothing back then, it was all my white relatives who were erased from my tree. In this land of the one-drop rule, born of this country’s obsession with keeping “white” at 100 percent, my black identity outweighed 75 percent of my biology. So how should I define race? Culture or biology? Nurture or nature?

Luther had a bout of lupus later the year that Aunt Dorothy visited us in New Jersey. It destroyed his kidneys, the first of his vital organs it would attack. He began life-saving dialysis three times a week that cleaned out accumulated toxins and fluids, wreaking havoc on the benefits of his medications, as they were cleaned out every other day too. During this upheaval, we became pregnant for the first time in our eight-year marriage. The news brought out the most joy Luther had ever expressed.

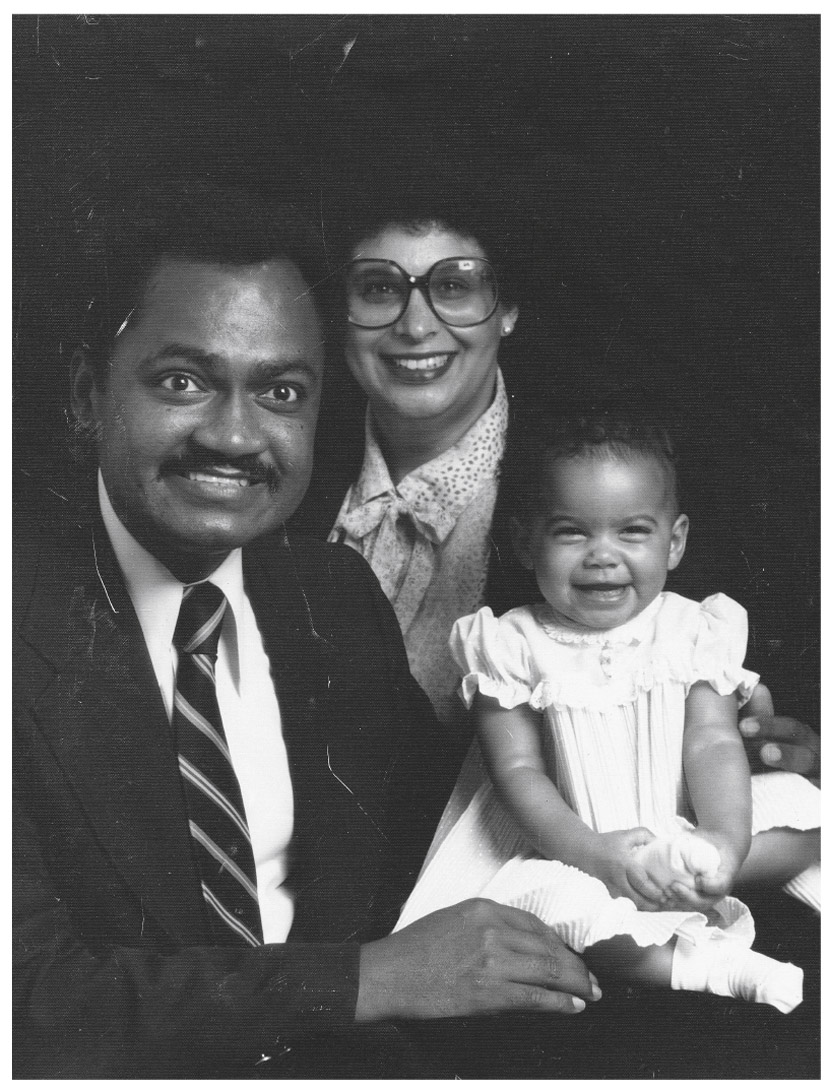

Jennifer was born in 1981, a child so white looking I couldn’t tell which baby was mine among the white ones in the hospital nursery. We thought it was my white heritage that made her that complexion, but a black woman pointed out the brown tops of Jennifer’s tiny ears as her natural color. Sure enough, our daughter morphed into a brown child. Jennifer was a precious brown baby born into a different world than we’d known, into an extended white and black family that claimed and loved her from the start.

Luther, Dolores, and Jennifer, 1981.

It had been two years since Mama and Dorothy reunited, so they planned another visit, this time in Buffalo to meet Charles Nathan, David, and their families. While on maternity leave, I would go too, and introduce the baby. But the difference in our black and white worlds drove a debate among us Jacksons about where they should stay.

“They can’t stay here at the house,” Mama said. “They might be scared in the ghetto around all these black people. What if they act like Angela’s sister did that time she came to Buffalo?”

“That woman musta been scared the black would rub off,” David said. He thought if Dorothy stayed with us in the ’hood, we’d be sure she was OK with black folks. But Mama said it was too much. I don’t know what excuse Mama used for not extending the hospitality of her home, but she booked Dorothy and Antoinette in the Holiday Inn on the white side of Buffalo.

To create just the right setting for the family to all meet, Mama wanted us to all go out to dinner on their first night in town. But our family rarely went out to dinner because of the cost, so nobody knew where to take them. One night at work she talked it over with her white nursing supervisor, who suggested a waterside restaurant with a private dining room.

At the restaurant, the hostess showed Aunt Dorothy, Antoinette, Mama, me, and the baby in her little seat past the lively happy hour to that private room. There we found David and his girlfriend, Clarissa, and Charles and his wife, Gee, dressed up and waiting for us. As Mama introduced each one, Dorothy leaned in and kissed them warmly. The aunt and cousin who had embraced me showed the same love to each one of them. Her “I love you” was so heartfelt, so simply honest, it seemed as if she had always been one of us.

The setting was lovely. We sat around a large wooden table, surrounded by soft white lights strung through lattices and vines. The privacy of the room made for conversation we could all join in, and the opportunity to speak freely. As Mama presided over the union of our black and white family, the most beautiful thing in the room was the blissful glow in her eyes. It was her dream come true, watching them lean in over their plates, getting to know each other and weaving our colors with love into whole cloth.

The next morning, David drove them over to the house for coffee and Mama’s cinnamon coffee cake. As we milled around the kitchen fixing our coffee, Mama showed Dorothy her Buffalo Bills football game tickets under a refrigerator magnet. She and David bought them every year along with community bus tickets to the stadium. She loved eating BBQ with the crowd while somebody else did the driving.

Not to be outdone, Antoinette said their Indianapolis Colts would be way out front of the Bills, and Aunt Dorothy rattled off their players’ statistics like a sportscaster. They had a favorite sports bar where the family went together to watch the Colts over burgers and beer, she said.

Those two old ladies gave tit-for-tat, their version of trash talking about who would be in the playoffs and have a chance at the Super Bowl. Raising the ante, David and Antoinette traded phone numbers so they could rub in insane plays and victories after game time. By the following season, the two of them were traveling to attend Colts-Bills games together, hosting one another in Buffalo or Indianapolis. And on a future visit, Mama and I went to their packed sports bar to see the Colts play on a bewildering number of wide-screen TVs.

When the football talk died down, we sat at Mama’s dining room table, which was dressed in the good white tablecloth, special blue glass plates, and a peony bouquet from her garden. As we settled in, Angela arrived, her hair freshly teased into a white bouffant. She was still Mama’s best friend from forty years in the Clique Club and was the last of the old gang still in Buffalo. Mama introduced Angela as her other sister, the one she’d been through it all with.

I served slices of that mile-high coffee cake while Angela told how she and Mama had raised us kids like cousins, especially me and her daughter Sandra. It was true. I was godmother to Sandra’s son and could hardly remember a special occasion without them.

“Angela was the heart of our fun,” Mama said. “Her house was full of parties when the kids were little, and she organized our families for more get-togethers than you could shake a stick at.”

They had so much more than fun together. The two of them had made the shower favors by hand when both Sandra and I got married, cooked dinners together for church fundraisers, visited every Christmas, and cried together after their husbands died.

“The whole nine,” Mama said.

Dorothy studied the woman who had filled her sisterly shoes the thirty-six years Mama had been missing. “I’m grateful you had each other,” she said. “It’s a blessing to know you.”

Angela reached across the dining room table and took both Mama’s hand and Dorothy’s. “You two don’t know how lucky you are, getting back together,” she said. Her eyes were weary when she turned to Dorothy. “My white family doesn’t know about my black family. They’re so prejudiced, I can never tell them. I have to live a lie, a double life.”

This was old news to us Jacksons, and I think Mama must have already said something about it to Dorothy. But Antoinette’s lips parted, and her eyes flared momentarily, bearing witness to how little the uninitiated understood mixed-race life.

Those two women would meet again. Some years later, Mama was found in the morning, unconscious in her evening bath, the water turned cold. A neighbor noticed she hadn’t taken her morning newspaper in and called David. Mama had had multiple seizures sitting in that water all night long.

Angela and Dorothy sat together in Mama’s hospital room. Their mutual devotion to her brought them there faithfully every day until I could fly in. Then they mothered my frightened self and stayed on when I had to go back to work. Sandra, who worked at the hospital, checked in with the staff every day on Mama’s care. After Mama came around and Dorothy went back to Indy, our constant Angela never missed a day beside my mother, sitting sentinel until she was released to rehab weeks later.

Five years passed as Jennifer grew, Mama and Dorothy kept up, and Luther tried to make it through work, despite his continual decline from lupus. Then, in May 1987, he was found dead in his hospital bed, his heart destroyed by the unfiltered residues deposited by the dialysis that was only so effective. He was forty-five. I was thirty-nine. Fourteen years after we met, Luther was gone.

After six years of deacons praying over him, new doctors, changing medications, waiting for a transplant and clinical trials, Luther died quietly in his sleep. We had not been able to fix him. I had believed we could.

I took five-year-old Jennifer to the funeral parlor for a private viewing. We stopped in the dim light of the foyer before she saw what she did not expect. She had gone to the hospital with Luther some Saturday nights, their dinner packed, storybook and games in tow. She saw the blood from his body cycle through transparent tubing and back into his vein. She heard the alarms when his or somebody else’s blood pressure went haywire. She saw the dialysis chair he was strapped in flipped upside down to keep him from fainting. But she had not understood.

“You know Daddy has been very sick for a long time,” I said as we stood in that foyer.

“He is? You didn’t tell me.”

“He was sick, and, well it got so bad that Daddy died, honey. We came here so you can say good-bye to him.”

“He died? Daddy died? That’s not fair!” she cried. “Everybody has a daddy, but now I’m not going to have mine?”

Mama didn’t ask the Boehles to come to that funeral either. But she was right at my side, the best person to help me. I had been very stressed for some time with Luther’s illnesses, my too-demanding executive job, and raising my little one. She knew I could barely cope.

As a single working mother, I spent the next three years just putting one exhausted foot in front of the other. All the house, yard, taxes, bills, teacher conferences, entertainments, and parenting responsibilities I’d shared with Luther were now mine alone. But the hardest part was when Jennifer tried to make sense of her little life. She couldn’t remember her father’s face, so I put his picture next to her bed. She questioned if the dark circles under my eyes would ever go away, or was I sick like Daddy? She burst out sobbing in the movie when a mother bear was killed. She begged me not to go to work and leave her.

It escaped me then, but functioning independently caused me to grow, to trust my own judgement, and become self-reliant. With the help of a live-in babysitter and Mama’s helpful visits, in a few years, I came to live life on my own terms.