19

Belonging

Everywhere

We moved back to the States where Jennifer finished eighth grade at the local public middle school. But after the rigors of her private French international school, our public school had fewer classes at her level. She was fluent in French by then, something too valuable to lose. Jennifer had gone to that private school because my company offered to pay for education of expat children in schools where they could keep up their native English. But now that she was going to high school, we had to decide where she would go.

We visited two private high schools recommended by black friends whose children attended them. To send Jennifer to such a white environment would be going against Luther’s prior refusal to consider private schools.

He had good reason. At the age of three, she went to a preschool in New Jersey touted for its stimulating program. In a converted old mansion, teachers led educational activities and documented Jennifer’s progress in regular written reports. We were well pleased, until the day I dropped by unexpectedly. When I opened the heavy wooden door, loud James Brown music filled the foyer. Several young white teachers had Jennifer and Clarence, the only other black child, dancing as they egged the kids on to wilder movements. The teachers clapped out the rhythm, pointing to the children and laughing at them. No white kids danced in this minstrel show. The white people I paid a fortune to train and protect my child had turned her into a ridiculous darkie to entertain themselves. Yet they were surprised when I demanded they stop, then laid out the headmistress and them. That institutional racism made up Luther’s mind. It proved to him that most whites, even if well meaning, self-declared liberals, cannot or will not see or cop to their part in keeping black people down.

Later, when a private elementary school approached us about enrolling Jennifer, Luther refused to consider it. Pulling on his short beard, he said public school had been good enough for us, and it would be good enough for her. She would be comfortable there. He wouldn’t risk his baby being mocked or mistreated as the only black kid in a hoity-toity school like that. She’d lose her black culture. Then what black man would marry her, he asked. Because certainly no white one would.

It was important that Jennifer knew where she came from, so I worked hard to steep her in black culture and history, even as she lived in white environments and loved her white relatives. We talked about how the civil rights movement won African Americans unprecedented access and opportunities, a point often revisited when we entered hotels, libraries, and restaurants. She celebrated African family and community values during Kwanza. We attended Jack and Jill’s curated events for black children raised in white environments, and Jennifer sang in the children’s gospel choir at our black Baptist church. On our way to France, we went to Senegal and visited Gorée Island. That scorching white-sand outpost, the largest slave trading center on the West African coast for four hundred years, horrified my nine-year-old Jennifer, and me. It turned our stomachs to see firsthand how our ancestors were held and shipped out in chains to become slaves in the Americas.

Knowing who she was and being able to maneuver in white spaces served her well when faced with discrimination. When a racial slur was slung at her during sleepaway camp, she twisted the boy’s arm behind his back until he apologized, while other campers cheered. I cheered too when she told me about it, because Jennifer stood up for herself when confronted with the trouble every black person knows is possible. She just had to work on using words instead of physical assault.

In the end, I thought Jennifer could handle going to a private (read white) secondary school. She was strong academically. She certainly knew how to function in white environments, having lived with white kids in the suburbs and in France all along. She was a beautiful, polished girl with a great transcript and a million-dollar smile. She was bilingual and was also familiar with Ebonics, having grown up with some Buffalo family that spoke it. Jennifer applied to two top schools and got into both.

At the first parents’ weekend at St. Paul’s School, she took me to see the other black students who competed with her for scholarships and introduced me to others. Some of those black girls from another scholarship program later called Jennifer an Oreo—black on the outside, white on the inside. Probably the real rub was some jealousy about her friendship with a boy from the ’hood, over which a few of the girls threatened to beat Jennifer up. But Jennifer was different from them. As I saw it, her time living on the Riviera, her white friends, her spot in the ballet company and King’s English weren’t black enough for some of them.

They were girls like I had been; diamonds in the rough whose academic success had won them a place in an elite institution. They clung to community among their own, just as I had at Harvard, because I didn’t fit in the mainstream, and wasn’t sure I wanted to. For me, black friends were essential to survive, and I think that was so for these girls too. You had to line up with the all-black-all-the-time or be deemed a sellout. Sadly, those same girls Jennifer introduced me to at parent’s weekend later crossed the street rather than speak to her. If my father was still alive, he might have called that another instance of “equal opportunity racism,” blacks hating on their own for not staying in their prescribed box.

Jennifer went on to Brown University, where she embraced everything that was in her and reached for so much more. She studied history and did musical theater. In concert with the Africana Studies Department she stomped out African dances to urgent drums in a tattered slave dress, then tap danced in a production of A Chorus Line. Fascinated with other cultures, she did a semester abroad at Al Akhawayn University in Morocco. And from that experience she went on to Princeton, did research in Algeria, and earned her PhD. While there she worked alongside a dean to prepare minority candidates to make their PhD applications as strong as possible.

I taught my African American daughter that she was entitled to try everything, that she belonged everywhere she chose to go despite anyone who said differently. That’s what personal power looked like to me, building on the hard-fought gains and experiences of her black and white family, to reach for whatever she chose.

Jennifer made me proud, the way she embraced these ideas. Yet her approach to the world of privilege was nothing like mine had been. I had clung to other blacks while trying to survive the foreign world of Harvard’s power and whiteness. Instead, Jennifer went through the Ivy League assuming her place with friends from all races, religions, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Unlike the carefully crafted public masks I had put on in white environments at her age, Jennifer is her same self with everyone. It had never occurred to me, all those years I tried to give her the best of the striver’s ambitions Harvard had imprinted on me, that she would become so much more facile at navigating such an advantaged worldview.

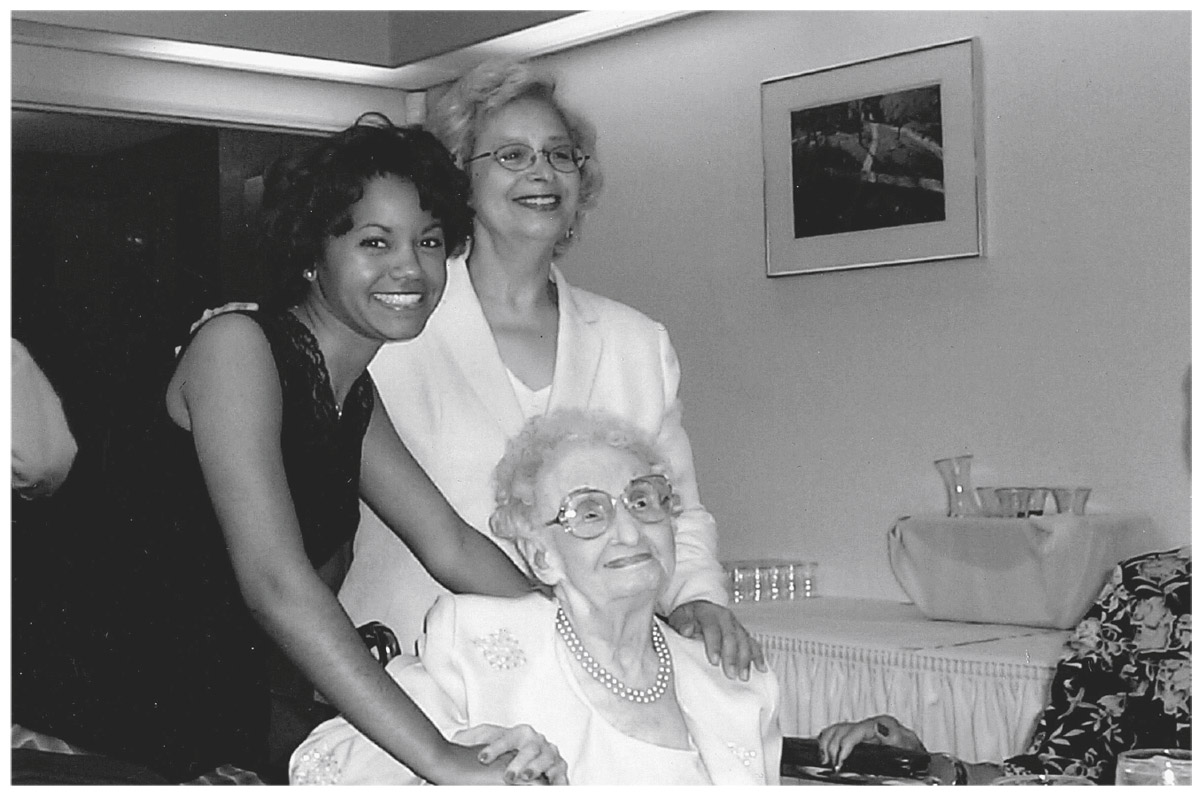

Mama and Dolores with Jennifer at her college graduation.

After graduating from Princeton, Jennifer taught African history to a largely first-generation college student body at City University of New York (CUNY) in the Bronx and Harlem. It was the same university her father, a first-generation student from Harlem, graduated from with an engineering degree.

When she started that position, Jennifer found out why she had been selected over other candidates from Ivy League colleges. During an interview, she had mentioned a summer college job she had picking produce on a farm in Norway with a migrant worker from Central Europe. In a turn away from professional internships, she wanted a completely different experience and place.

Jennifer loved being outside by the glistening fjord backed by green mountains. But that migrant farming proved to be hard work. She slept on a cot in a barracks and squatted until her knees ached picking strawberries in long low rows or climbed ladders and reached until her shoulders were sore picking cherries off trees. For ten hours a day, in brutal sun and pouring rain, and under the night lights if the crop was too ripe, she did her business in the fields because there were no toilets. When she got back, her main advice for me was to always wash produce carefully.

Two generations before, her black grandparents had worked southern cotton and tobacco fields for a living. When I told my elderly mother-in-law in North Carolina what Jennifer was doing, she replied, “You said what? She pickin’? I thought you were sending her to those fancy schools up north so she wouldn’t have to.”

And yet, that subsistence life experience had influenced the CUNY faculty to choose her for the professor position. Some thought she would better relate to the hardships of the nontraditional, largely first-generation student body at CUNY.

Jennifer knows how most African Americans struggle regularly with job and wage discrimination, inadequate and unaffordable housing, health disparities, police harassment and shootings, food injustice, racially motivated misconduct, insensitivity, and inhumanity. While she has not had to face such strife in her own life, she knows her many privileges were won through our own family struggling against that very list of inequities. Like all our country’s non-white minorities, we both know that simply having brown skin can not only block any opportunity but also bring about grave harm.

I taught Jennifer she belonged everywhere because that was my own belief and goal. In addition to holding onto my beloved black community, I went for jobs, friendships, and residences that spoke to my broadest interests and opportunities, sometimes where few other blacks were to be found. For years, certain black friends have wondered how and why I wasn’t living in the ’hood and socializing exclusively in the black community. Some of them never socialize with whites.

“Why you wanna live over there in that white neighborhood?” a black professional friend asked me. Without waiting to hear how I loved access to the subway, banks, jobs, and ready amenities available around the corner that are harder to find in the ’hood, he told me nothing could beat living among his own, where he was fully accepted. He wouldn’t dream of putting up with trying to get along with white people in his private life, even though there had been multiple homicides in his neighborhood, one a block from his house. There, he didn’t have to edit his cultural tendencies, see people cross the street in fear as his son approached, or be ignored by neighbors who acted like he didn’t exist.

Another friend said it like this: “A white man in my bed? Not gonna happen. I need the comfort of brown skin next to me. Somebody who knows and loves my culture like I do.”

The black skepticism about the way Jennifer and I live no doubt comes in part from racist hardships they know about, the ones we all know are possible, as well as having no loving relationships with whites. While Jennifer and I are surely African American, being shaped by my mother and her white family’s example that race should not matter has stretched our view. It’s a dream, we know, but the one we hold out for, no matter that I won’t see it in my lifetime.