2

Dress Box

Our relatives in Georgia and Alabama were only names and stories to me, except for Great-Aunt Willie in Birmingham. When I used to sleep over at Grandma’s as a girl, she had me write letters to Willie. Daddy said Grandma went to night school for twenty years to learn to read and write, but the only thing she learned was the neighborhood gossip. Sitting at her feet, she’d pluck an unanswered letter from her wicker basket and dictate the reply to me.

“Dear Willie. Whatcha got, Dolores?”

“Dear Willie,” I’d read.

“Received your letter and was glad to hear from you. Whatcha got?”

“Dear Willie, received your letter and was glad to hear from you.”

“We are fine and hope you are too. Whatcha got?”

Most of the opening I’d already written before she dictated it; for years, every letter had had an identical greeting. Then we’d add the Buffalo updates and write similar content to others waiting in that basket. Our teamwork saved Grandma the extravagance of running up some long-distance phone bill she couldn’t afford. And all those letters to Willie gave me a sense of kinship. With Grandma’s blessing and help, I headed to Alabama.

It was no surprise the visit started with having to talk the reluctant white cabdriver in Birmingham into driving me to the black side of town. It had been fifteen years since their police dogs and maximum strength water hoses blasted demonstrating African American youth and a black Baptist church bombing killed four little girls. Maybe the driver took me because he knew I wasn’t a local who would put up with his excuses, or maybe he thought I was white.

When we pulled up, Aunt Willie came down off the porch of her bungalow where she waited for me. As that stately dark woman wrapped me in a warm hug, I caught the scent of pomade in her freshly straightened hair. She was dressed for company in a wrap-around dress, and she fussed over me as only a relative with southern charm could.

“Ooooeee, look at Charles’s baby come to see the old folk,” she said, and laughed easily. “Come on in, chile, and rest yourself a while. You thirsty?”

We spent Friday evening talking over news of the Buffalo family she hadn’t seen in decades. I delivered their messages and the recent photos they wanted her to have. She got acquainted with my mother and brothers too, none of whom she had ever seen. I, on the other hand, had to admit I didn’t know about most of the people she tried to fill me in on. But I promised to take the stories back to Buffalo.

Saturday morning, Willie and I sat out on the porch with our shoes kicked off, gently swinging in her old glider. It sat under the striped awning she kept down all the time against the Alabama heat.

“I heard you went to our colored college up in Washington. Is that right?”

I began telling her about my experience at Howard University, when she stopped me.

“Oh wait, here comes Miz Greene. Mornin’, Miz Greene. This is my great-niece come to visit from up north!”

“Well, I declare,” Miz Greene said, asking where from, for how long, who in my way back was related to Willie. Would she know them?

By her demeanor, it wasn’t clear if this conversation was courtesy or gossip fodder. I answered sweetly with just enough explanation to satisfy. “She’s my daddy’s aunt, from the Georgia side.” After further pleasantries, Miz Greene went on her way.

Aunt Willie kept interrupting our conversation to introduce me to the whole community as they passed by, from the postman to neighbors going to and fro. Since it seemed to make Willie proud of my visit, the way she put me on display for people I didn’t know, I made small talk with every person who said hey.

There was even one woman who came up on the porch to get a real good look at me. She used that southern cover-all for saying anything you want: “Bless your heart, honey.” Then she asked what she really wanted to know. “But is y’all really related? You don’t look nothing like Willie.” That was sure the truth.

I smiled at their curious glances, feeling at once part of the community that came to greet me and an oddity in it. I wondered if Willie had told them I had a white mother, something few Americans accepted, and I doubted few southerners of either race could abide.

Out on that porch is where I found out about Daddy’s first marriage. I knew he’d had a first wife, but she was never spoken of. “Weren’t she purdy?” Aunt Willie asked me, assuming I already knew what she was saying about Daddy getting married at seventeen. This was fascinating, so I didn’t stop her talking. But the bride I wasn’t related to was not the connective family story I came to Alabama to get. When I admitted to not ever having seen her, Aunt Willie walked me back to her room where she had a picture of their wedding day to find and show me.

“Look down under the bed for me, hehe, and save these old legs,” she said. “Now feel around for a dress box.” It wasn’t near the foot of the bed, so I scooted over to its side, lay down, and reached way underneath. There it was—a large box of sturdy cardboard. Squirming in closer to grab hold, I hooked my index finger into a pull cord that hung from inside the lid and pulled the box out. That once white box hadn’t been moved in years, judging by the gray clumps of dust Willie had to wipe off with a wet rag.

“They’re all in there, the family pictures,” she said. “Bring the box in the dining room where we can see ’em good.”

I set that heavy box on her lace tablecloth and she wiggled the lid off slowly. Inside were hundreds of black-and-white and sepia-toned pictures thrown together, jammed to the top. Some were shiny, or with scalloped white edges, or fixed to standing frames under some laminate. Every person pictured was black, very dark black. No wonder the porch people had stared so.

More of my history, identity, and roots were in that box than I’d hoped to find on this visit. And Willie was ready to help me understand what they each had to do with me.

“We have to dig through this to find that wedding picture,” Willie said. “It’s in there somewhere.”

“Good, I want to see that, and will you also show me the other family in here I don’t know?”

She started with the photos on top, a lot taken of her and her husband’s occasions at church and with friends. After some stories about her life in those shots, I politely asked to just see relatives. She had no children, but for the next hour, she showed some with mostly her husband’s people. I thanked her for sharing, then when I finally explained how much I wanted to understand who my own blood relatives were, Willie began sorting pictures in earnest.

In one, Grandma stood wide-legged in an overcoat, squinting into the camera on a sunny day. She was about the same age in the picture as I was at the time, around thirty.

“Ain’t you the spitting image of Belia? You both got that white side, see?”

“What white side are you talking about?” I asked.

“Ain’t they told you ’bout it?”

Willie said Grandma and her cousin Acie were born to the two Doster sisters that had been raped repeatedly by two white brothers. The men’s family, named Riley she thought, owned the Georgia farm where the sisters worked, in Smithville. They were teenage girls in 1890 when Grandma was born, on the same farm where her ancestors had been slaves.

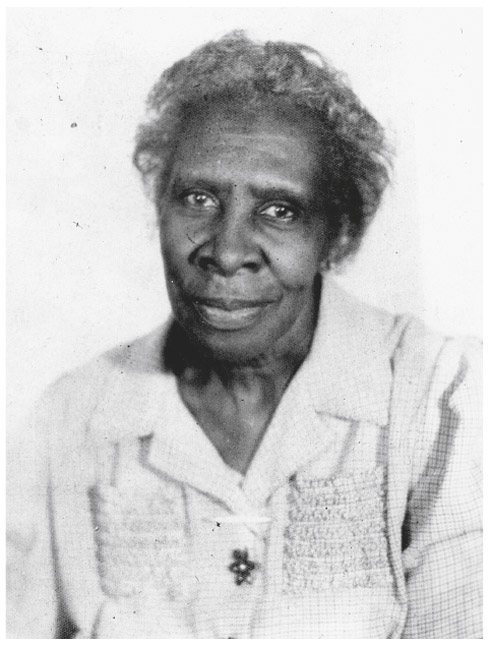

My great-grandmother Frances, who was raped.

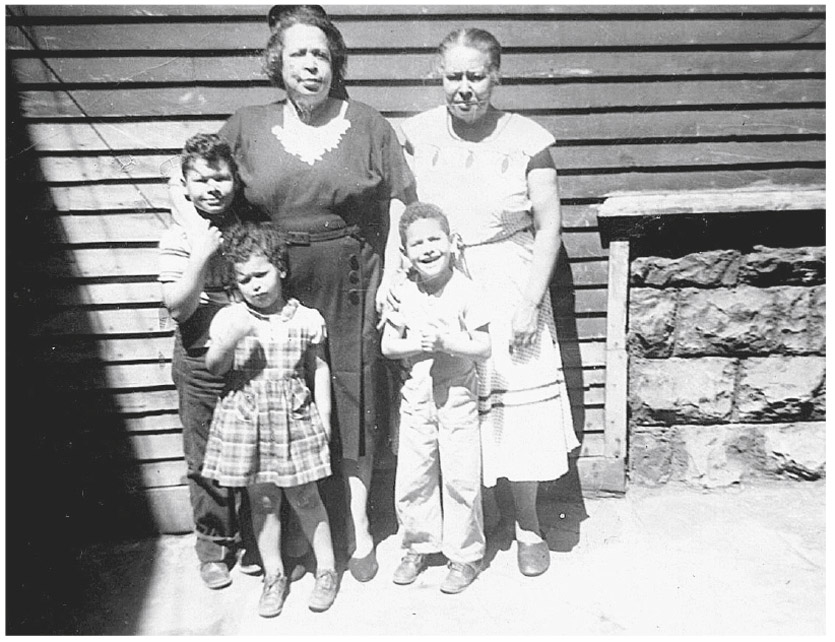

Aunt Acie (left) and Grandma with my brothers and me. All of us were half white.

Great-aunt Acie, who I met at her place on Sugar Hill in Harlem, was pretty white looking but, like me, was unquestionably black. While the connection between her and my grandmother had never been clear to me, I’d just assumed she and Grandma were part of the chalk-to-charcoal spectrum of black people’s coloring.

My throat caught as the horror sunk in. That old Massa privilege had been forced on my great-grandmother fifteen years after the Civil War? How had Grandma lived with the pain and humiliation all these years and never talked about her mother? I didn’t know what to do with my outrage, sitting with the aunt who reported this as flatly as the weather forecast. That must be why Grandma called leaving Georgia “escaping.”

It gave me a new pride in my grandmother, knowing she’d had the gumption to leave. She’d made a plan, probably having to sneak her family out to get away from the Smithville whites who wanted to keep their heels on her neck. I’d never known that old lady now crippled by arthritis had that kind of courage and drive. I’d never known Buffalo was her promised land.

“I guess she didn’t tell me about that because she was ashamed,” I said.

“’Shamed? Naw, everybody knew white men did that whenever they got ready, and there wasn’t anything we could do ’bout it. In your great-grandma Frances’s time, there still wasn’t no getting away from those men. She was ripe, you know, sixteen or so, when she birthed Belia.”

“Did Grandma know her father?”

The whole family knew him. Willie could still picture that white man. He’d come around once in a while with a bag of candy and set Grandma on his knee. But they all knew better than to try to claim that open secret beyond the front porch.

So that’s what flowed in my veins, a white plantation rape. It was one thing to read about slavery rapes, but the subjugation of my own grandmother and her mother sickened me. Yet I would have to carry that rapist’s blood with me always, not in shame but in anger. And though I didn’t know it then, finding his stain wouldn’t be the last time the discovery of an ancestor would change who I thought I was.

Aunt Willie went back to the box, like Grandma’s story was nothing. She went on showing me other relatives whose names I’d heard but relationships I’d never grasped. As we talked, I began to lay their pictures out by sibling groups on the lace, filling half the table. I went and got a pad and pen to make notes so important details wouldn’t be forgotten. When I got back to the dining room Aunt Willie had poured us her homemade sweet tea, the mark of southern hospitality. We sipped from tall glasses with lots of ice, and she pulled down the shade against the sun that had already heated up the house.

We got right back to it, the old lady as excited to tell the stories as I was to hear them. She showed me the people in Florida who sent us oranges at Christmas, people in Philadelphia, cousins I’d never met in Manhattan, people still in Georgia. Grandma’s first husband, Nathan, a slight, dark railroad man who shoveled coal to fuel the engines was in a fading group picture. Willie told me he was killed on the rails in a poker fight and brought home to Grandma by his black coworkers in the back of a mule-drawn cart. Daddy hadn’t told us anything about this father, either. But then Charles Nathan was obviously named for him.

I asked if she knew of any African ancestor of ours who was brought to the States. Such an identity-anchoring heritage seemed essential to me after watching Roots.

She nodded. The story of our African forefather had been told to her by her own parents. She said we came from a man who was brought on a slave ship to Virginia and was then sold to a Georgia plantation. Willie never knew his name. But she worked backward in time through the photo genealogy laid on that table to the timeframe when he came. We figured he was probably born about 1840, only two generations before Grandma.

Holy Moses, I am African, I thought. It felt like a lifeline from my belly had been strung through all these generations of people on the table and tied off in his. Many years later, Ancestry DNA testing would confirm his origins in Togo and Benin in West Africa. But back then, in the initial tug of my connections, I was suddenly somebody, much more than just my nuclear family, Grandma, and the Buffalo relatives. Even though I’d never meet these kinfolks, now I had generations behind me. I wrote it all down then to capture their stories.

As I did, Aunt Willie continued to dig around in that dress box. “Looky here,” she said, handing me one of those laminated five-by-seven pictures. The sepia-toned photo of Daddy as a very young groom showed him to be trim and serious in a suit. I recognized him, that same strong build and wide nostrils. He stood next to a brown-skinned girl with marcel-waved hair in a drop-waist dress.

“Told you she was purty,” Aunt Willie said. “Take it. You should keep the picture.”

I wondered why Daddy never talked about that marriage. Was it because divorce wasn’t accepted back then? And why get married at seventeen? Here were more secrets, like Grandma’s white father and her husband’s murder on the train. Grandma and Daddy had kept big parts of their earlier lives from us kids, as if they could erase their Georgia history.

But it wasn’t erased anymore. All they lived through had become part of me. From my African beginning, through generations of plantation slavery and the rape of my formerly enslaved great-grandmother, to my father’s migration out of the South, I was firmly convicted of my black roots. There were emotional ramifications to sort out, but I could go home and code switch all I wanted, as a proud black woman.

The next morning before I went home, Aunt Willie returned to the pictures we’d left on the table. “You want any more of these to keep?”

I took that one of Grandma standing wide-legged to see later if we really did favor, and a couple of recent ones of Willie to show the Buffalo family. We put the rest back in the box and I pushed it under her bed. Before getting into the black cab company’s car she’d called for me, I kissed Aunt Willie and hugged her tight, wondering if she had any idea how much she’d given me.

Luther gave over the dining room to me so I could lay out the family history. A chart was typed on a legal-sized page with rows of siblings and their mates, noting marriage, birth, and death dates. When the stories were written up, the chart and Willie’s photos were added and bound into books. They were ready in time to pack for our trip to Buffalo for Christmas. I couldn’t wait to see my family’s surprise as they unwrapped each of their own keepsake copies.

With everyone gathered for the holiday that morning, Mama’s favorite cinnamon rolls, which had risen next to the heat vent overnight, were going fast. When the last bathrobe and bottle of Old Spice were opened and the wrapping paper thrown out, I said there was one more present, a special surprise. That was Luther’s cue to get the family history books down from our bedroom.

“Remember when I went to see Aunt Willie last spring?” I said. “All the family history she gave me has been written down in these books. Here’s a copy for each of you.”

“Wow, Dolores,” David said, sticking his hair pick into his outsized Afro.

“Our African forefather is in there,” I said. “Like in Roots.”

“For real? You found our African,” David said. “Too cool, my sistah.”

Charles Nathan looked his over like it was an ugly Christmas tie. He was the most disengaged from the family, so I should have known he wouldn’t make much of our history. Why had I thought he would care?

Daddy pulled out the genealogy chart, which was folded to fit in the 8½-by-11 binding, got out his magnifying glass, and studied the information, penciling in a few more details.

“What the hell is this?” he said, looking at the picture of himself as a seventeen-year-old groom. “I can’t believe you’d show this to your mother.” I said nothing, having triggered him to pour the first Four Roses of the day into his coffee and grumble about not wanting to see “that woman.”

Mama said never mind, that marriage was ancient history that we kids always knew on some level. But her long-standing rule still stood: “I don’t want any talk about her in my house, Dolores.”

I should have thought of her feelings, and so said I was sorry. But they were missing the historical point. The picture was meant to show off our handsome young father, not his ex. We’d never seen his younger years.

David came over to where I was standing to save me. He put his arm around me. “I always wanted to know about the whole family, my beautiful black history. Thank you,” he said “Now, come on, Daddy, you know we all wanted to see how dapper you were as a young lady-killer.” David could say anything to Daddy because those two had a special bond. They’d been a pair of soul brothers since way back when they fell into that stupid old Amos ’n’ Andy routine.

“Just tear off the ugly half of the picture if you and Mama don’t want to see it,” David said, and laughed as he mimicked the slow rip up the middle of a picture.

Charles Nathan hadn’t said anything. As his white wife thumbed the pages, he looked on with a weak pretense of interest. Maybe he thought it was just another of my bookish tangents, a project nobody else in the family would see the point of doing. Or maybe he was quiet because he was never much of a talker.

Later, over Mama’s delicious feast, Daddy had warmed up to the notion of talking about his life and started telling family stories. About his brother and wife from New York who passed through town with a woman in tow who was sawed in half in a magic act. About all the raccoon, possum, rabbit, and sparrow dinners our country relatives could fix six ways to Sunday. About how one of Grandma’s white laundry customers in Smithville trained him as a gentleman’s valet for her husband. That was where he learned etiquette, polite company language, professional grooming, and attire. It was delightful to laugh and learn together about the brighter sides of the father we’d seen beaten down by racism in his later years.

I was happy that Christmas because I’d made it back to center, authenticated by my multigenerational African American family. Unfortunately, that steadiness only lasted until spring.

Then I was another kind of lost.