21

Leaning into Brown

Jennifer’s Skype call rang one night from St. John’s island where she was vacationing with her white boyfriend. They came up on the screen together, looking quite pleased, a festive ocean view restaurant in the background. Noticing her glam earrings, I said, “You’re so dressed up for a beach trip.”

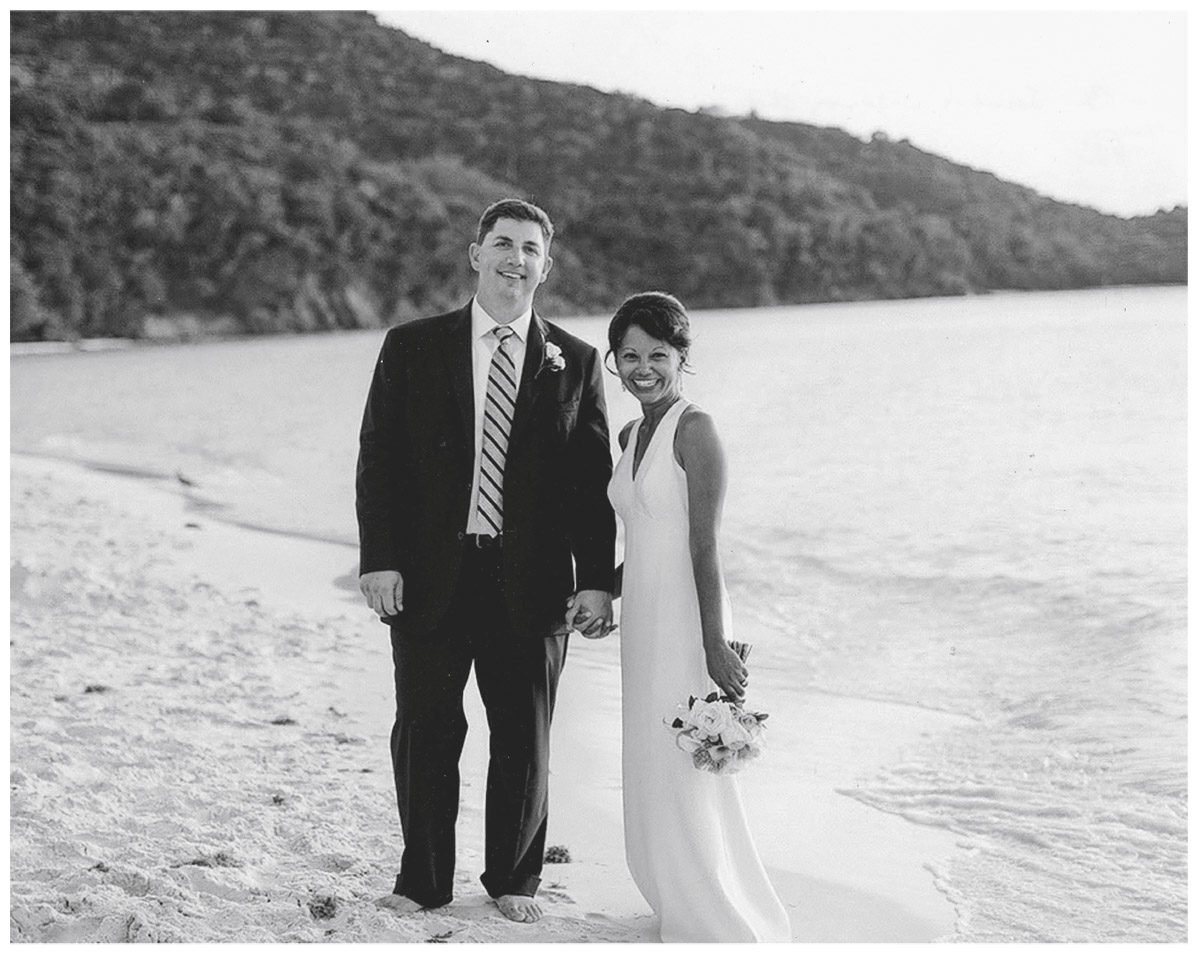

“Because we got married today!” They grinned at each other, holding their ring fingers up to the camera. Craig panned Jennifer’s white dress and tropical bouquet. “Island Mike officiated, here on Trunk Bay. The weather was gorgeous.”

“What? What? What?” I said. “You got married?” I paused a minute, trying to get it through my head. “Wow. Well, congratulations.” What else could the mother of a thirty-six-year-old college professor say? So, yeah, they were mature enough, compatible, and in love, and had been together for a couple of years. The joy on their faces was everything a parent could hope for.

“We’ve saved you the price of a big wedding,” Jennifer said, laughing. “We didn’t want all that. Anyway, the random swimmers and sunbathers out there cheered for us.” They’d secretly planned it all—a photographer, a hairdresser, the license in St. Thomas, and the officiant with the best wedding website.

After their continued honeymoon, I arranged a reception in Boston. Craig’s parents flew in for the party and Jennifer’s new father-in-law gave the toast while white and black guests from several generations wished them happiness. Like the 66 percent of Americans who told AARP it was OK for family to marry another race, they were happy for their son.

Jennifer and Craig married in 2017.

It was all good until we parents posed for the family picture with the couple. It hurt that none of my family who should have been at such an occasion were there, because they were already gone. Daddy died in 1980, lupus took Luther in 1987; then David, Aunt Dorothy, and Charles Nathan had all died in turn.

But it was Mama I missed most. How I wished the one who had helped raise Jennifer was still alive to see how free her granddaughter was to marry another race. If only Mama could have lived to see that Jennifer did not have to say she was dead and go in hiding for fear of violence against her husband, like Mama did in 1943. There Jennifer stood, her champagne glass aloft as her white father-in-law gave his blessing, crisscrossing the boundary of her white grandmother’s foray over the race line. And like her grandmother, Jennifer says her mixed marriage doesn’t change her blackness, just the way Mama said her mixed marriage didn’t change her whiteness.

I wished Mama could see how alike we three generations had turned out. We were all women who chose to cross over and embrace other cultures, following in her footsteps to sidestep race norms for the lives we wanted.

These days Jennifer and her husband are my window into the millennials who reject race boundaries. Like their mixed peers, they are people who had jobs, educations, or social circles that put them in contact with each other. Like any other couple, their bonds are based on common values, interests, and shared experiences. I know how true that is listening to the animated academic conversations between my daughter and her fellow professor husband in their own language—pedagogy, publishing, and syllabi. And like my mother, their focus is having a loving family.

Some mixed millennials I’ve spoken with ask, “What is the big deal?,” perhaps not understanding the price paid by couples decades ago. Like the black bride who was surprised to learn that my parents couldn’t be seen together in public back in 1942 Indiana nor the risks attached if they were.

Black adult children of my friends who chose white spouses have been supported by their parents. Most had “the talk” before the wedding. Do you know what you are getting into? What does his/her family think? Are you sure? Even the parents who secretly acknowledge that they hoped their children would marry black spouses who understood their culture and understood how to maneuver in the white world have stepped over the race barriers with them. They want their children to have happy marriages. They understand times are changing.

It was evident how things were changing when I went to my local community center for a Loving Day party. The hall was full of mixed-race families at the event marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision legalizing interracial marriage across America. So, like the Irish do on St. Patrick’s Day, I went to celebrate my own heritage(s).

A woman with skin colored just like mine welcomed me warmly. Somebody asked later if she was my daughter. I wandered about slowly, taking in the Asian, black, Hispanic, Native, and white adults with their blended children of every combination. The variety of skin tones, hair textures, and eye shapes were as familiar as the old Clique Club gang and my own face, like we were all somehow related. It felt good to be surrounded with the normalcy of mixed race when the public had made an issue of it all my life.

It reminded me of what I’d seen on an excursion in Cuba. Dianelys, the Havana tour guide with cream-colored skin, told our group of African American travelers we had a lot in common. She said, like all Cubans, she was mestizaje—mixed with African blood. Their 1959 revolution, so the official explanation went, was a racial democracy, where everyone is equally Cuban first and race mixing a part of who they are. That dream, though not completely true, sucked at me like undertow, pulling me to the place I’d never been able to articulate I wanted to see in America.

The same woman who welcomed me to the Loving party had a video camera hoisted on her shoulder, capturing people’s family stories on film. When she approached me, I gave the thumbnail of Mama’s disappearance and reunion with her family. Others standing nearby smiled. nodding acceptance. Like they knew exactly what my life had been about. Like their own lives were somehow parallels. No questions were necessary about why Mama ran, or how my parents struggled as a mixed couple, the questions whites always ask me. These people already knew. It was my turn to smile, to not feel like a freak with some abnormal life. I relaxed into what I came for, a sense of belonging in my own tribe.

Party organizers began their remarks by announcing that Loving Day was being celebrated that day in cities across the United States. There were family parties like ours going on at much bigger Mixed Remixed Festivals and street happenings in Brooklyn and Los Angeles. There interracial people are so common the press has called them havens. There were also parties in many unexpected places, like Griffin, Georgia, and Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The speakers painted the picture of America’s rising interracialism. First, they cited the 2000 Census, which listed sixty-some race categories that could be mixed for the first time. Before that, I would have fallen into mulatto or quadroon mixed-race Census categories, which were on the forms from 1850 to 1920. Those were designations slave holders and Jim Crow politicians used for decades, lest anyone with black blood pass over into whiteness. In 2000 I had filled in my own Census form by checking both the black and white races, excited that my country had really seen and affirmed me. I was no longer restricted to marking just the box for blacks, in denial of Mama.

I’m in my seventies now, wondering if the United States will ever move past its racial strife and resulting fears about race mixing. It’s just so ingrained.

Yet I have seen the perception of race mixing move from illegal and dangerous to a growing demographic today exceeding seventeen million Americans.

My interracial kind can now be found in high places. While enjoying a certain acceptance and even popularity, the mixed-race love my parents helped pioneer in the 1940s has not been fully embraced. Barack Obama was chosen president twice, then rebuked by the election of a racist named Trump. Meghan Markle married into Britain’s royal family but faced media backlash, including a family photo portraying their baby as a monkey. Advertising implies the use of mixed-race actors imbue their products and us with some greater common humanity. As if antimiscegenation was never a thing. But, as America would have it, this normalization message is not shown in regions where it might aggravate viewers.

In my family, Jennifer and her husband expect to live their interracial life in peace, because they live in an area where it is not much of an issue. But they are clear-eyed about the fact that brown skin can bring trouble. At one of our Sunday lunches, they agreed to prepare their little mixed-race son for the systematic and interpersonal conflicts he will face.

They plan to teach him how to be safe in this time of police brutality and white terror because mixed people are still black in America. And, like the four generations of my family before him, my grandson will have to face people trying to stop him from naming himself and defining his own place in society.

I have hope because my family, black people and white people together, have embraced love across the color line for the last seventy years. So have the growing millions of other Americans who have discovered that love triumphs over race. While that trend will accelerate, I don’t know how far America will move in this direction.

But what I do know is this:

The American identity is in flux, leaning into brown. A significant portion of our citizens will push past the barriers of family racial separation the way Mama, Aunt Dorothy, Jennifer, and I have. Continually growing numbers will look beyond color to marry the partner they love, raise the children they want, and unite with family branches of different races.

And yet, racial strife still dominates American life. I can’t see the United States ever adopting the theory of racial democracy the way Cuba espouses, where mixed race is a popular notion. Our intrinsically white supremacist culture, which wants to keep their race pure and in power, makes that clear every day. Because of them, all us mixed, black, and brown families will necessarily protect ourselves by remaining vigilant and fighting everything from microaggressions to police shooting unarmed minorities.

Meanwhile, when my family is together, color is not our focus. Me and mine, and the millions of others who choose mixed-race families, are going to keep on loving.