Romantic reminders of days gone by were the clubs just outside the Seattle city limits. During and after Prohibition, these roadhouses were jumping with activity. Seattleites could jump in a car and drive out to have some semi-illicit fun.

On the drive from Seattle north along Victory Way were the Coon Chicken Inn’s Club Cotton on the right and then the Jolly Roger on the left. The Coon Chicken Inn opened in 1930, and in 1933, it opened the Club Cotton in its basement for drinking and dancing. According to the Post-Intelligencer newspaper, the Jolly Roger opened on July 2, 1934, when Prohibition ended. Prohibition in Washington State lasted from 1916 to 1933.

Tales abound about the Jolly Roger, including its tower being used as a lookout for police raids, its “cribs” (tiny bedrooms) in the basement being used for prostitution, and the tunnels beneath it that could lead one to safety during a police raid. True or not, these tales have been a part of Seattle-area myths for nearly a century.

County tax records prior to 1934 show no building on the Jolly Roger parcel. On December 15, 1933, ten days after the appeal of Prohibition, Gerald Field, a Seattle architect, submitted the plans for the Jolly Roger to Dr. E. B. Fromm, the builder. The King County assessor’s record states that it was built in 1930. Perhaps this was confused with the Coon Chicken Inn, which was built in 1930, a theory that Vicki Stiles of the Shoreline Historical Museum brought up in her research. Stiles also questions whether a tunnel existed beneath Victory Way to the Coon Chicken Inn. In her research, Stiles states, “Another story says that the tunnel connected to the Coon Chicken Inn, but the grandson of that establishment’s owner assured us that his grandfather would not even acknowledge the presence of the Jolly Roger, so it’s unlikely that there was a friendly tunnel between the two places.”

True or not, tales continue to swirl around the dance clubs built just outside Seattle city’s touch.

THE CAVE SUPPER CLUB MENU. The supper club would be a part of the nightclub scene in Vancouver, British Columbia, until 1981. According to Chris Wolfe, “This was a major spot in downtown Vancouver and just thousands of acts went through there over the years. The inside of this place as it was actually built to look like the inside of a giant cave! . . . Great atmosphere, and a real theater nightclub.” (Author’s collection.)

CAVE SUPPER CLUB MENU (INSIDE). The Cave Supper Club opened on Hornby Street. Richard Main said, “My uncle and aunt, Dave and Lillian Davies, owned the Cave club in the 1950s. I remember them complaining about how difficult and egotistical many of the big-name stars were, in particular Diana Ross.” (Author’s collection.)

COON CHICKEN INN. The Coon Chicken Inn was founded by Maxon Lester Graham and his wife, Adelaide née Burt, in 1925 in Salt Lake City, Utah. In 1929, they opened their Seattle restaurant at 8500 Bothell Way across from the Jolly Roger restaurant. The signs read, “Coon Chicken Inn, unfair to organized labor,” in the above photograph taken during a labor dispute in the 1950s. (Courtesy of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, MOHAI, No. Pl-24093.)

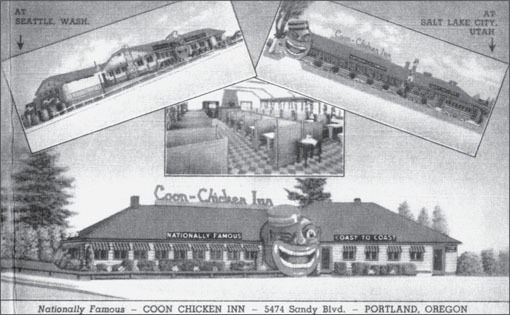

COON CHICKEN INN POSTCARD. This reproduction postcard shows the three locations of the Coon Chicken Inn. The Salt Lake City, Utah, location started with a small building that contained three stools, an icebox, and a small counter costing $50. The second location was in Seattle, and in 1930 the third location was added in Portland, Oregon. (Author’s collection.)

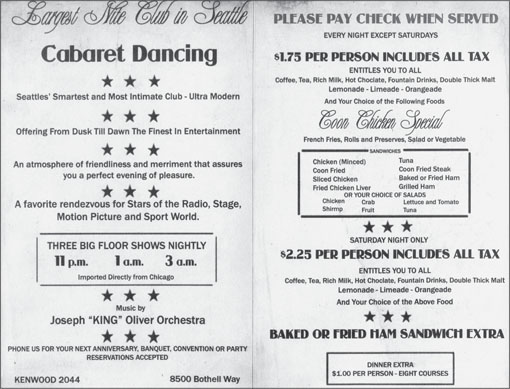

COON CHICKEN INN MENU. Maxon Lester Graham wanted to attract children to his restaurants, who would in turn bring their parents. He decided on the gimmick of adding the famous head logo to the entrances of the inns. The logo was a huge, winking, grinning face of a black man wearing a porter’s cap. Outrageous red lips framed teeth with the words, “Coon Chicken Inn.” (Author’s collection.)

COON CHICKEN INN MENU (INSIDE). Prohibition in Washington State lasted until 1933 (notice that no alcohol is on this menu). The Grahams left the restaurant business in the 1950s and leased out the buildings to other restaurateurs. The Seattle site is now Yings Drive-In; the Portland, Oregon, location is currently Clyde’s Prime Rib Restaurant; and the Salt Lake City, Utah, location is the Chuck-A-Rama buffet. (Author’s collection.)

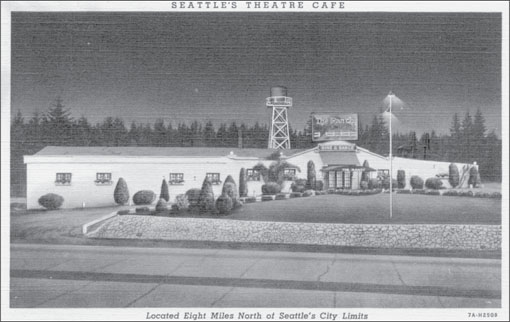

JOLLY ROGER ROADHOUSE. This 1935 photograph of the Jolly Roger showed a pink stucco building with a two-tiered tower located at 8721 Lake City Way. Vicki Stiles of the Shoreline Historical Society could find no evidence that the Jolly Roger had been a speakeasy, nor had the unique tower been used to warn patrons of police raids so they could slip away through a tunnel. Stiles did concede, however, that there might have been illegal gambling on the site, but that any tunnel’s existence has yet to be proven. (Courtesy of the Shoreline Historical Museum, No. 1982.)

JOLLY ROGER ROADHOUSE BAR. The Jolly Roger was a popular dance hall and restaurant. On October 18, 1989, the Jolly Roger was suspiciously destroyed by fire. Denchai Sae-Eal owned the building and was in a legal battle with Yeong Huei-Wen, the previous owner. Wen was in the building removing his possessions when the fire began in the cluttered basement. (Courtesy of the Shoreline Historical Museum, No. 2028.)

JOLLY ROGER MENU. This photograph shows the front cover of the Jolly Roger menu. The menu had a buccaneer theme with a pirate shooting two muskets over treasure on the background. A coffee cost 10¢ and a pint of beer cost 30¢, while a quart of beer sold for 80¢. A pint of Eastern Beer was 35¢ and a quart was 90¢. A minimum food charge of 50¢ was applied to each person. (Author’s collection.)

JOLLY ROGER MENU (INSIDE). The weekday hours were from 4:00 p.m. to 3:00 a.m., and on Fridays and Saturdays, it was open all night. Interestingly, the menu stated that, “Patrons Supplying Their Mixer Will Be Charged Our Menu Prices.” Coffee would only be served with food. On the menu were special full-course dinners that ranged in price from $2 to $2.50 and included chicken livers and giblets as well as sirloin steak. (Author’s collection.)

THE OASIS SUBURBAN RESTAURANT. This 1930s or 1940s color linen postcard shows the Oasis Suburban Restaurant, which was located at Aurora Avenue and 140th Street. Dancing and entertainment were from 9:00 p.m. until 2:30 a.m. daily. (Author’s collection.)

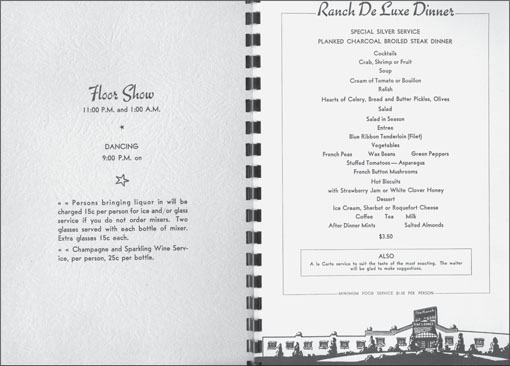

THE RANCH POSTCARD. The Ranch presented a floor show nightly, except Sundays. There was dancing from 9:00 p.m. until 2:30 a.m. with no cover charge. The Ranch restaurant operated during Prohibition and was located outside the Seattle city limits. (Courtesy of Mary Patterson.)

THE RANCH MENU. The Ranch’s menu featured a Western motif, with a cowboy on a horse with a rope and cacti. (Author’s collection.)

THE RANCH MENU (INSIDE). On the Ranch’s menu it stated, “Persons bringing liquor in will be charged 15¢ per person for ice and/or glass service if you do not order mixers. Two glasses served with each bottle of mixer. Extra glasses 15¢ each.” (Author’s collection.)