One

HILLBILLY BOOGIE

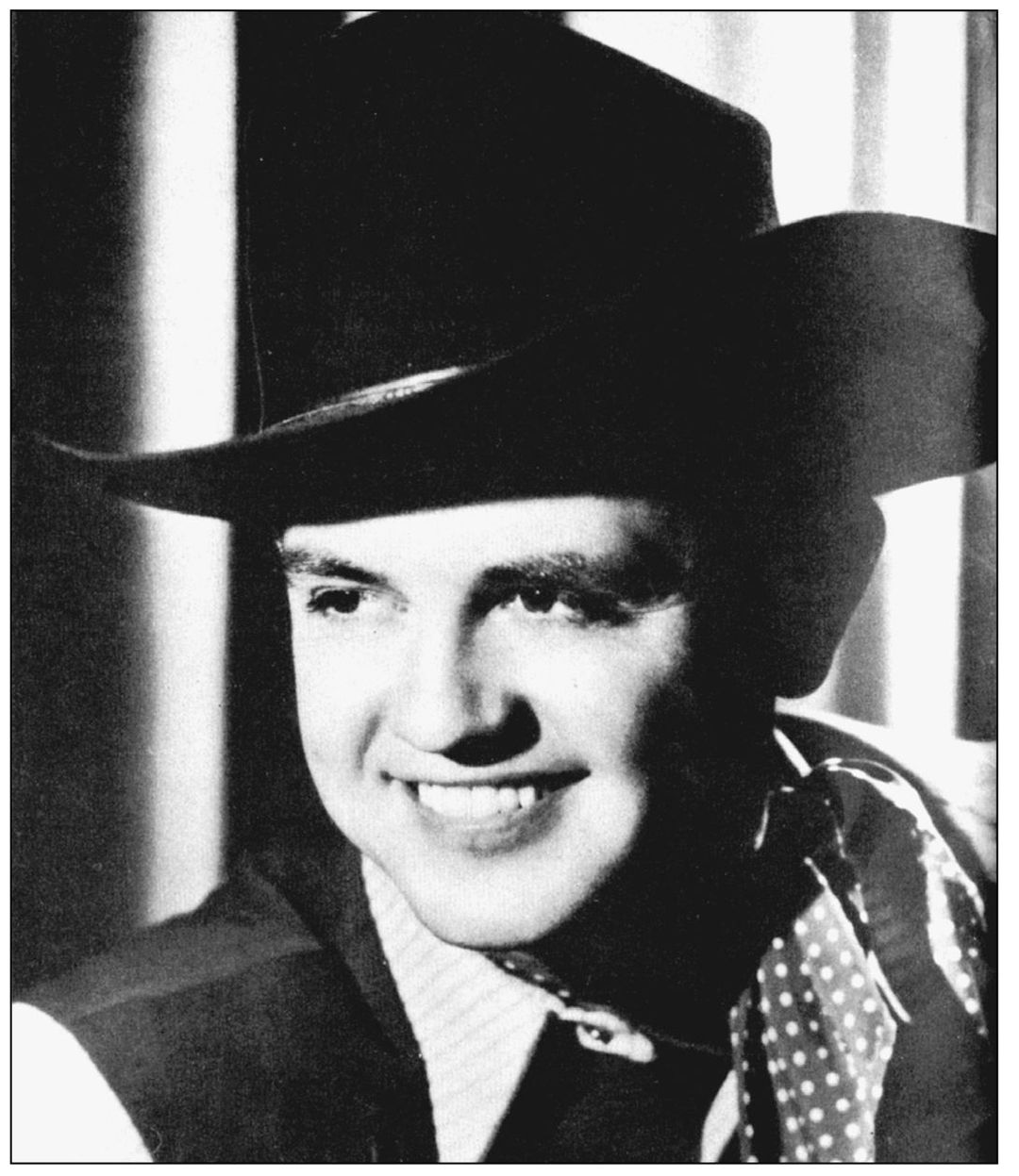

Lloyd “Cowboy” Copas, a native of Adams County, Ohio, sang on WLW’s Boone County Jamboree and on WSM’s Grand Ole Opry with Pee Wee King’s Golden West Cowboys. King Records signed him in 1945. The next year, he hit nationally with “Filipino Baby.” (Author’s collection.)

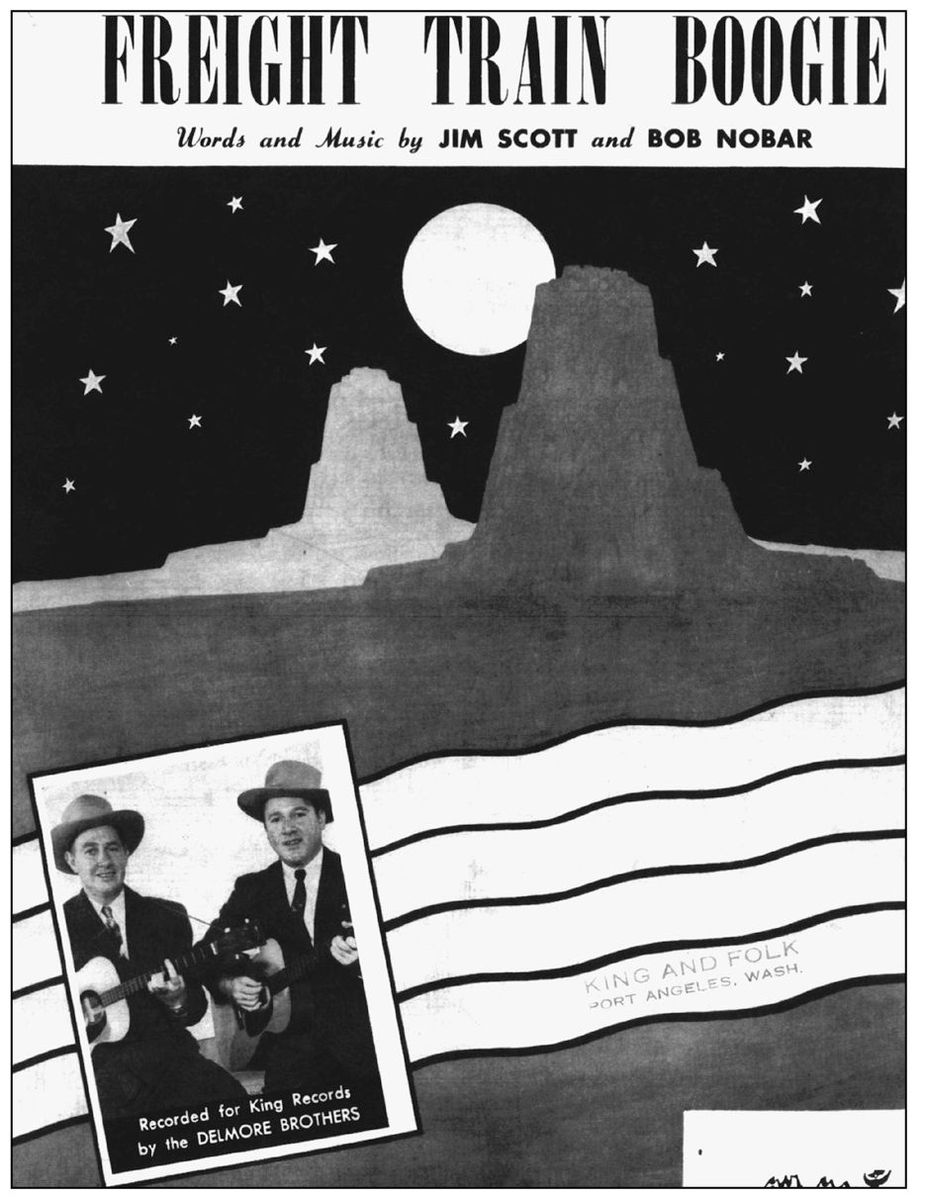

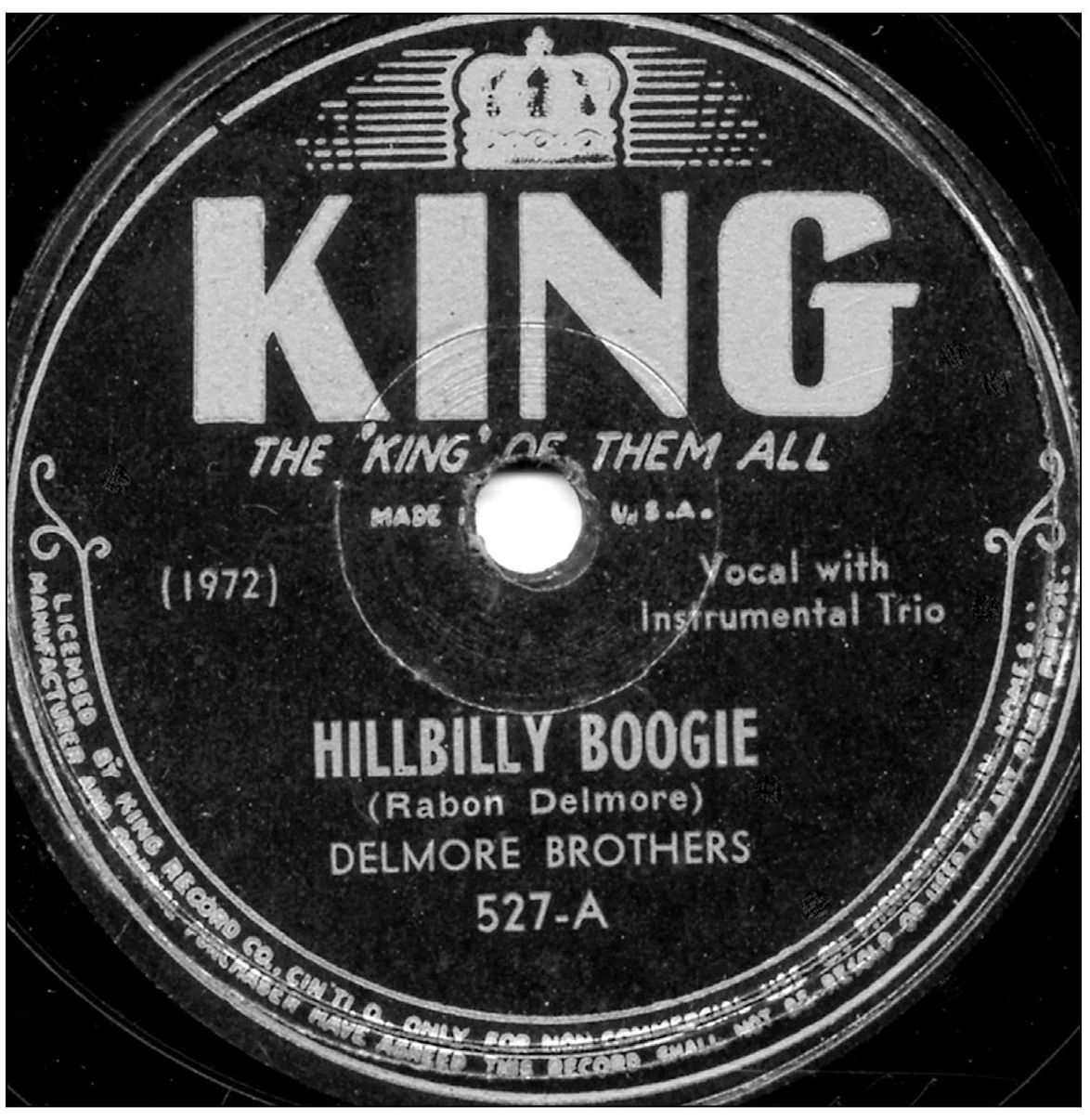

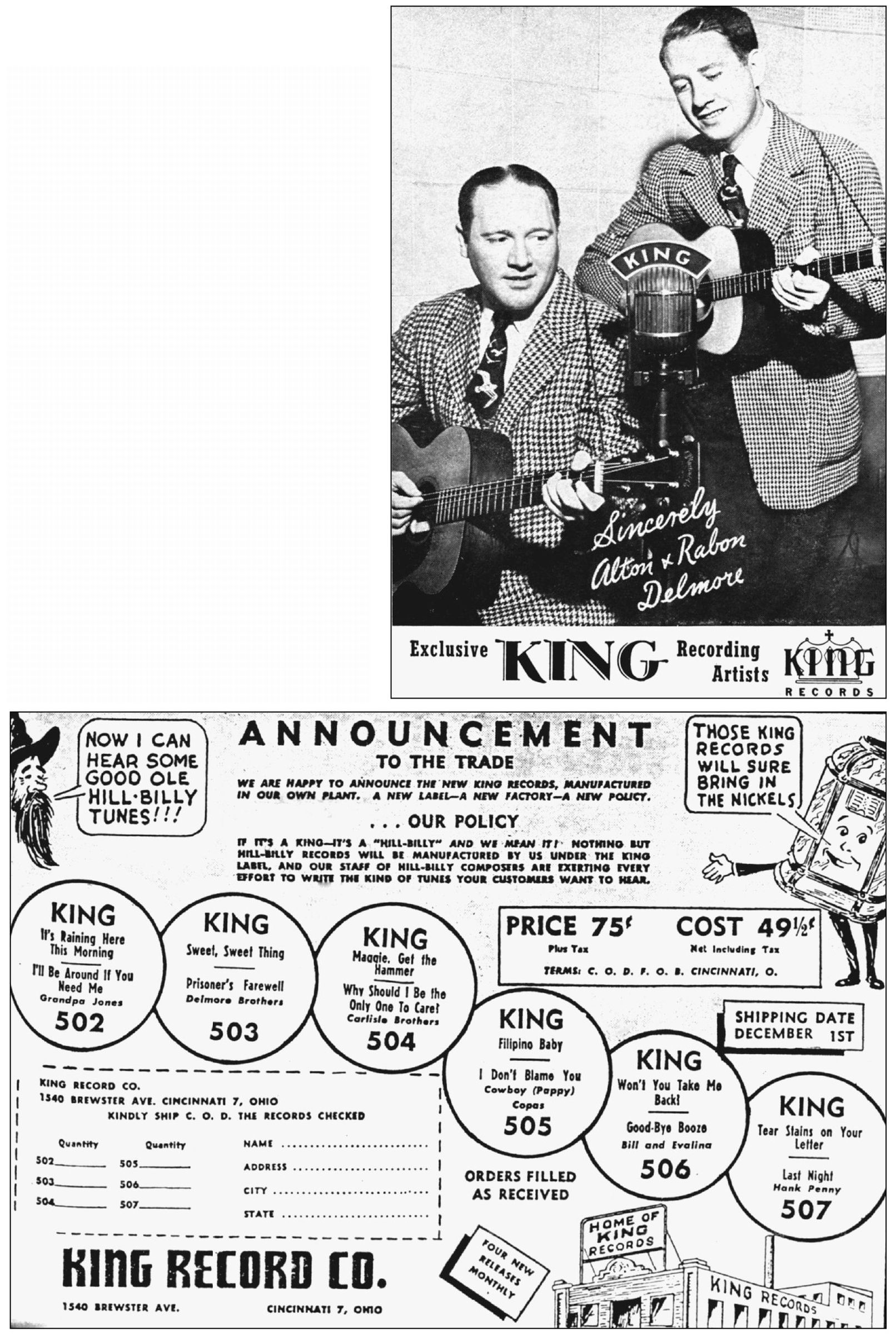

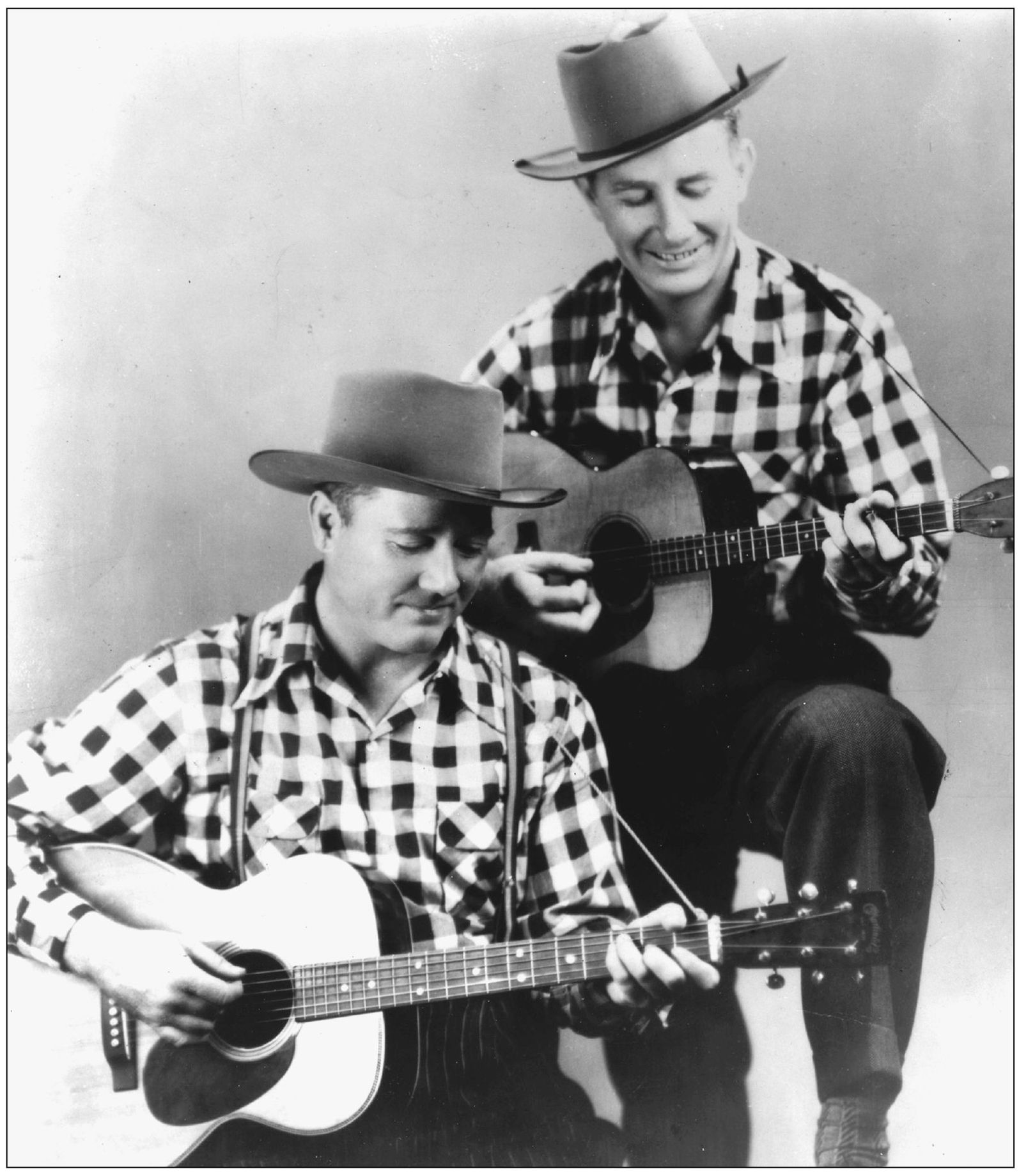

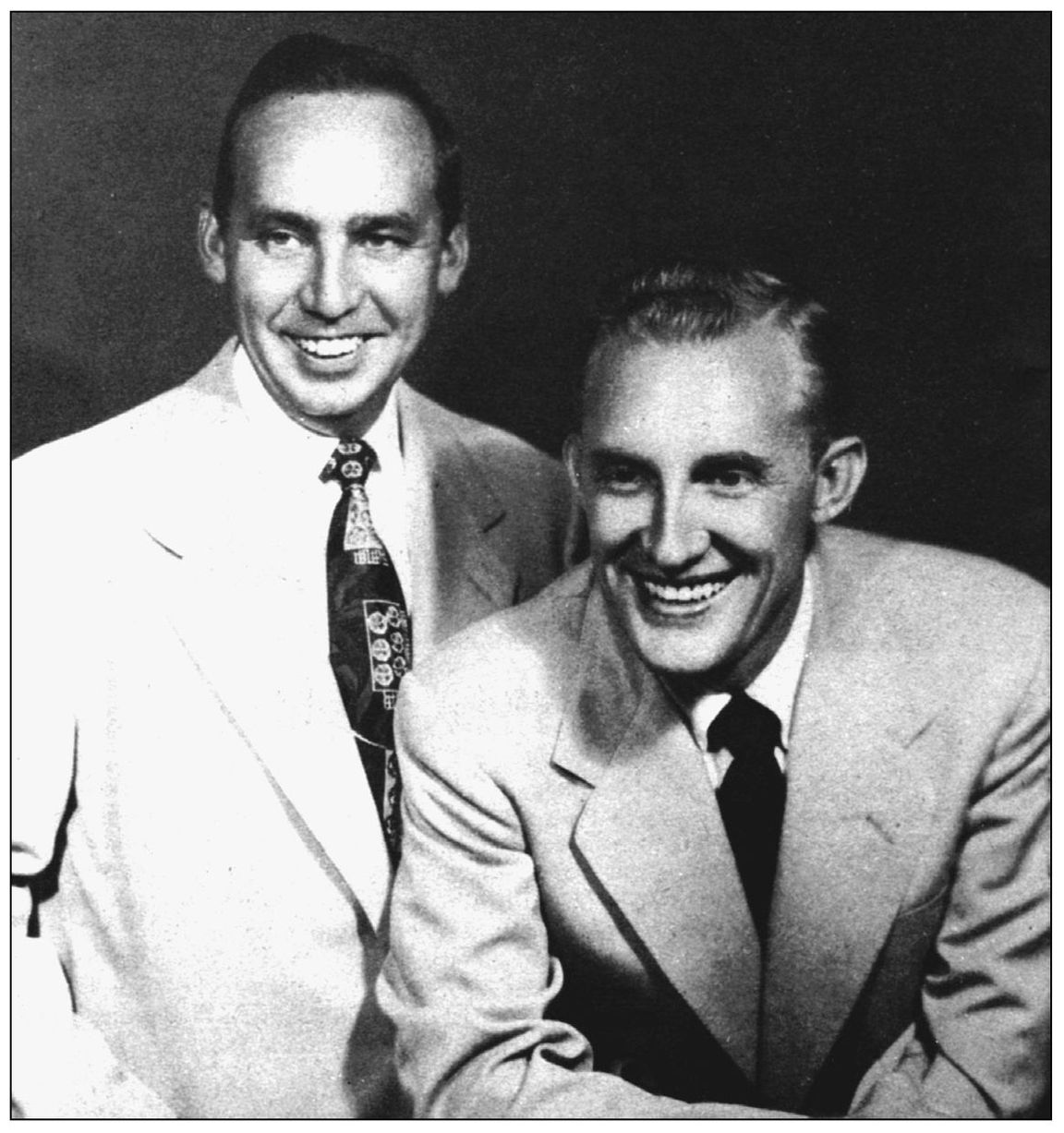

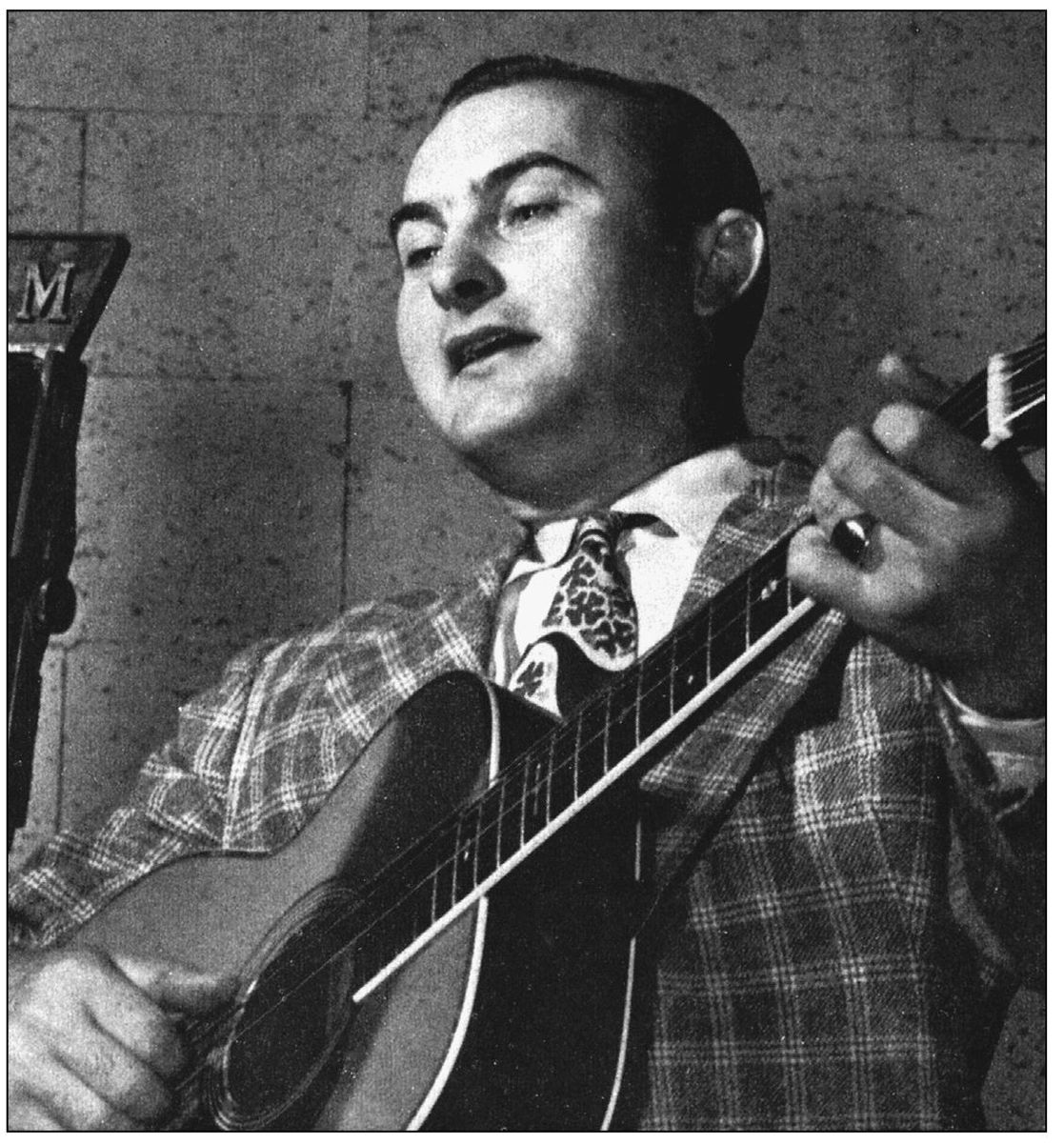

Alton and Rabon Delmore, the influential Delmore Brothers, cut “Hillbilly Boogie” and “Freight Train Boogie” for King Records in 1946. Their expert songwriting and musicianship helped establish the label’s fresh hillbilly sound. (Courtesy of Deborah Delmore.)

The Alabama natives were working as staff musicians at WLW when Syd Nathan signed them and gave their music a harder edge. By then, they were not newcomers to the music business. They had already played on the Grand Ole Opry and recorded for Bluebird and other labels. In 1949, they wrote and recorded—in King Records’ own studio—their biggest hit, “Blues Stay Away From Me.” (Author’s collection.)

Alton (left) and Rabon Delmore were versatile enough to sing, write, and entertain on WLW. They joined fellow station employees Grandpa Jones and Merle Travis to round out the Brown’s Ferry Four, a gospel group that later recorded for King. The c. 1944 advertisement below, one of King Records’ earliest, shows a small sketch of the factory in Evanston and announces new country records—then called hillbilly—for Grandpa Jones, the Carlisle Brothers, Bill and Evalina, Hank Penny, and others. Note the stereotypical long-bearded hillbilly character and the smiling jukebox. In the early years of King Records, Nathan actively sought help from the jukebox industry to bring his records before the public. His slogan was “If it’s a King—it’s a hillbilly.” Soon he would campaign to change the name to country music. (Right, author’s collection; below, courtesy of Zella Nathan.)

Syd Nathan achieved a successful and complete career redo, the first of many for him, on the veteran Delmore Brothers. Alton (left) and Rabon started on Columbia Records in 1931, cutting four sides, and then joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1932. They performed on the air for seven years. They switched to RCA-Victor’s Bluebird label for the next nine years, cutting 20 sides a year. In 1940, when they were well-known performers, they moved to Decca Records, recording 25 sides that year. By the time they were accompanying shows on WLW Radio in Cincinnati, their recording career had declined. But Nathan had faith in them. He signed them to a long-term contract with his new King Records in 1944. After they hit with King, they went to work for Memphis radio station WMC. (Author’s collection.)

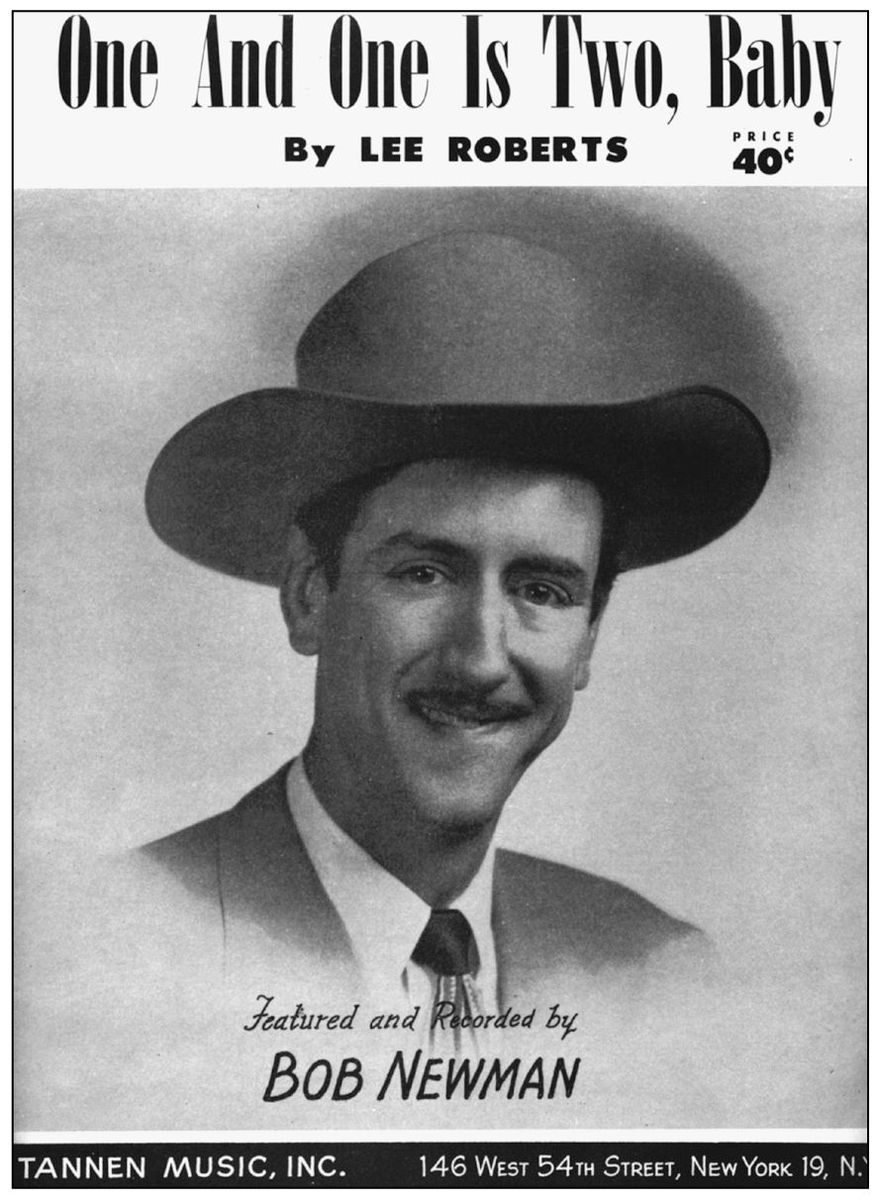

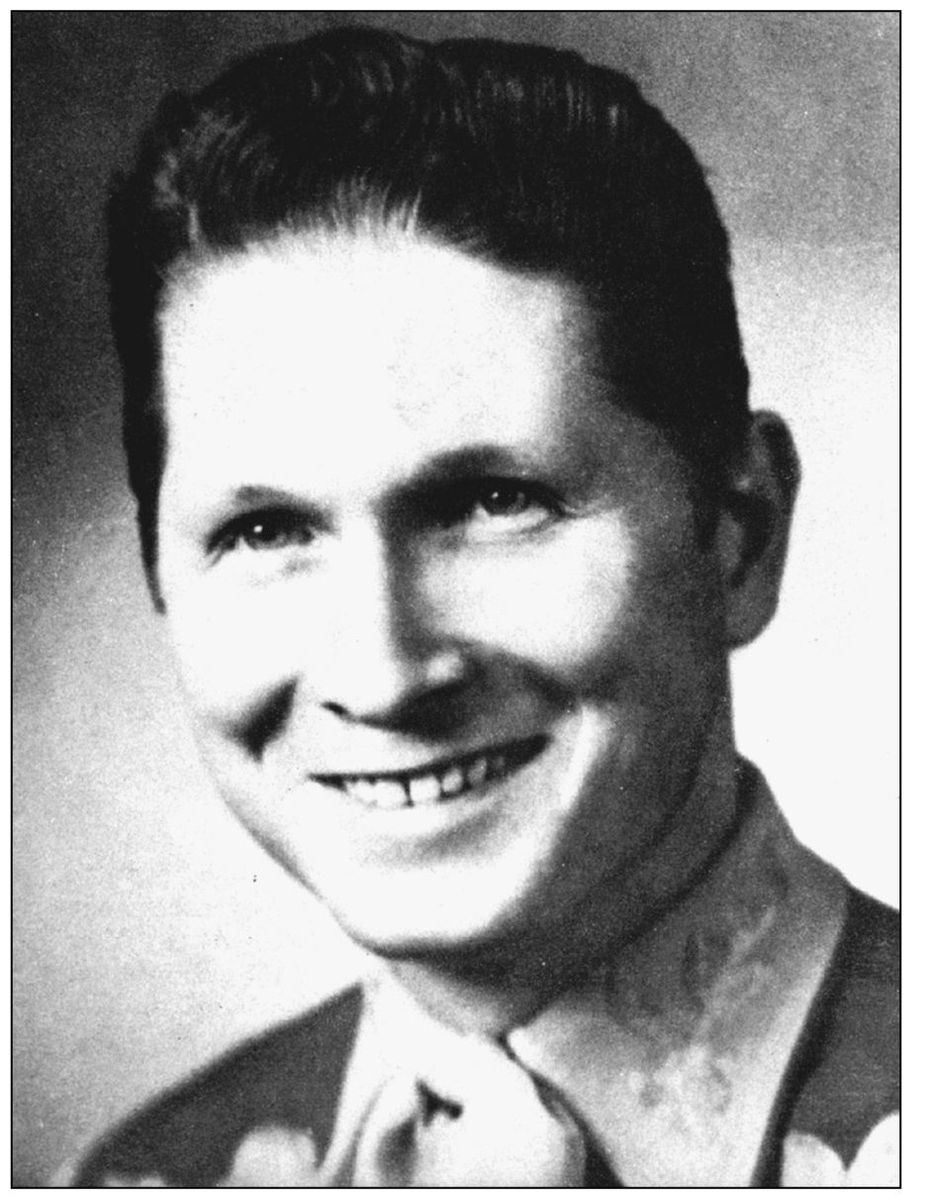

Country singer Bob Newman sang with the Georgia Crackers of Columbus, Ohio, before signing as a solo artist with King Records. In 1950, King Records released his “Cry Baby Blues” and “One and One Is Two, Baby.” He later became known for truck-driving records. (Author’s collection.)

The 78-rpm record pictured here, Newman’s “Quarantined Love,” shows another of Nathan’s innovations, the bio disc. He printed brief biographies of artists on promotional records, and sent them to disc jockeys and decision makers in the music business. The idea must have worked, for King Records continued to issue bio discs into the 1960s. (Author’s collection.)

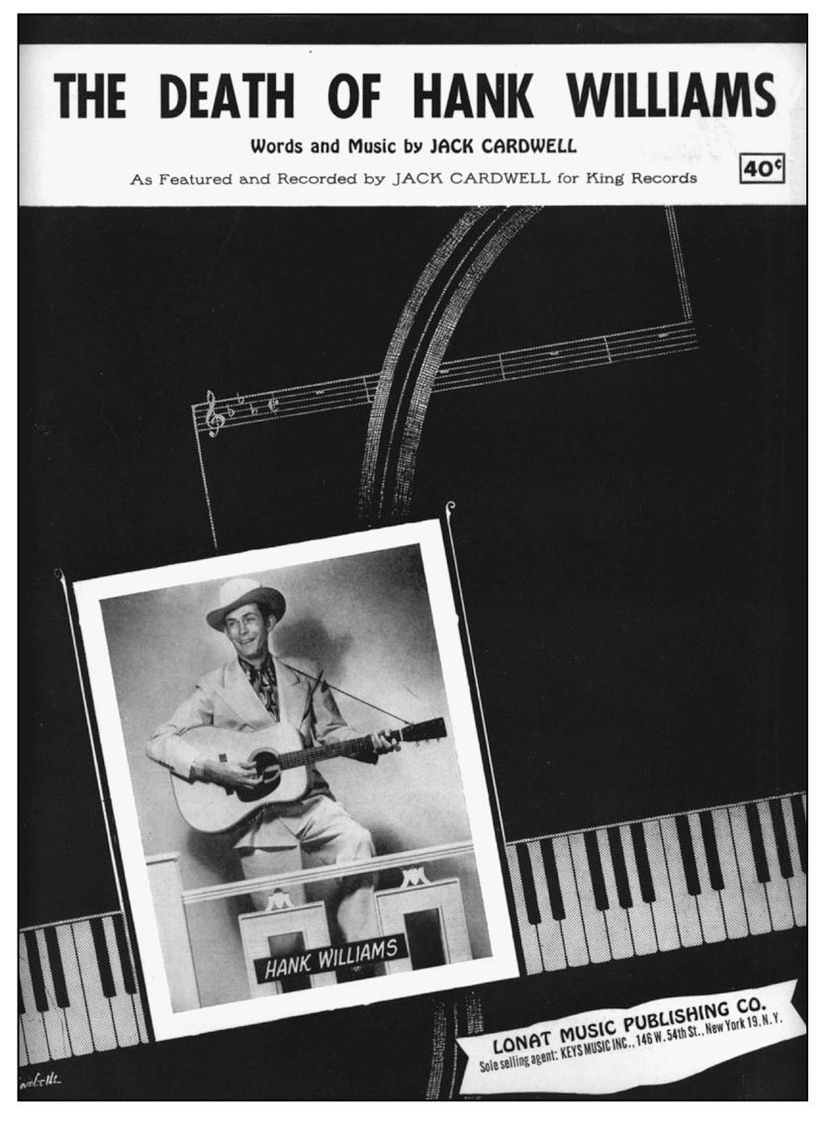

In 1953, Alabama disc jockey Jack Cardwell recorded two hits for King Records. He made the first, “The Death of Hank Williams,” in Mobile to exploit Williams’s fame. King ordered its pressing plant into hyperdrive. Williams died on January 1 of that year, and by February 14, Cardwell’s record had already peaked at No. 3 on Billboard’s best-selling country chart. (Author’s collection.)

At the time, Williams’s popularity was running so high that the sheet music publisher decided to place his photograph, not Cardwell’s, on the cover. (Ironically, a physician named P. H. Cardwell gave Williams a couple of shots of morphine before the singer died.) Jack Cardwell’s second and last hit for King Records—or any other company—was “Dear Joan,” a No. 7 hit that summer. He then fell from the charts and into the abyss of musical obscurity. (Author’s collection.)

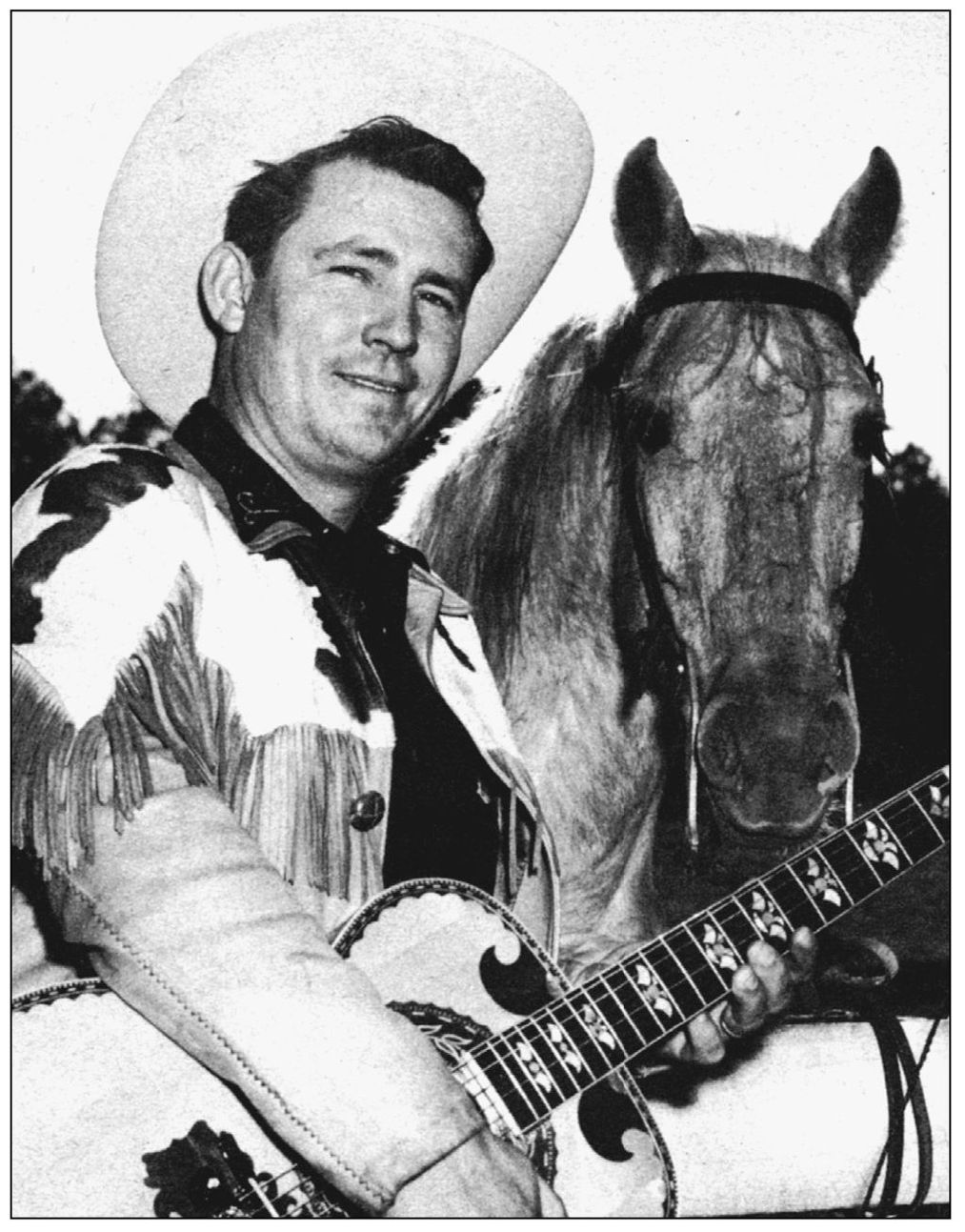

After Harold “Hawkshaw” Hawkins returned from the army in World War II, he sang in talent contests and appeared on WWVA’s popular Jamboree. One day, he sent a cheaply made demo to Syd Nathan, who nearly threw it away. Fortunately for the world, Nathan decided to listen to the shabby disc. The King Records chief then arranged to meet Hawkins and record four songs in a West Virginia radio station. Nathan once recalled, “The station was so small that I had to put the bass player in a closet and close the door because [by] even playing soft in this room, which was seven by seven feet, it was impossible to hear anything but the bass.” The much-shorter Nathan could not have missed the Hawk, who stood nearly six feet, five inches in his cowboy boots. He was known for his friendly personality, which led people to call him “Eleven Yards of Personality.” Nathan must have rejoiced upon signing yet another fanciful nickname. Hawkshaw and Cowboy Copas remained the bedrock of King Records’ country roster into the early 1950s. (Author’s collection.)

Kentucky natives Merle Travis and Louis “Grandpa” Jones were the first artists to join King Records. Travis became the one that got away. He quit his job on WLW’s Boone County Jamboree and left for California. The move proved fortuitous. He sang the From Here to Eternity theme, wrote “Sixteen Tons,” and became a respected guitarist. In 1946, he recorded “Cincinnati Lou,” on Capitol Records. (Author’s collection.)

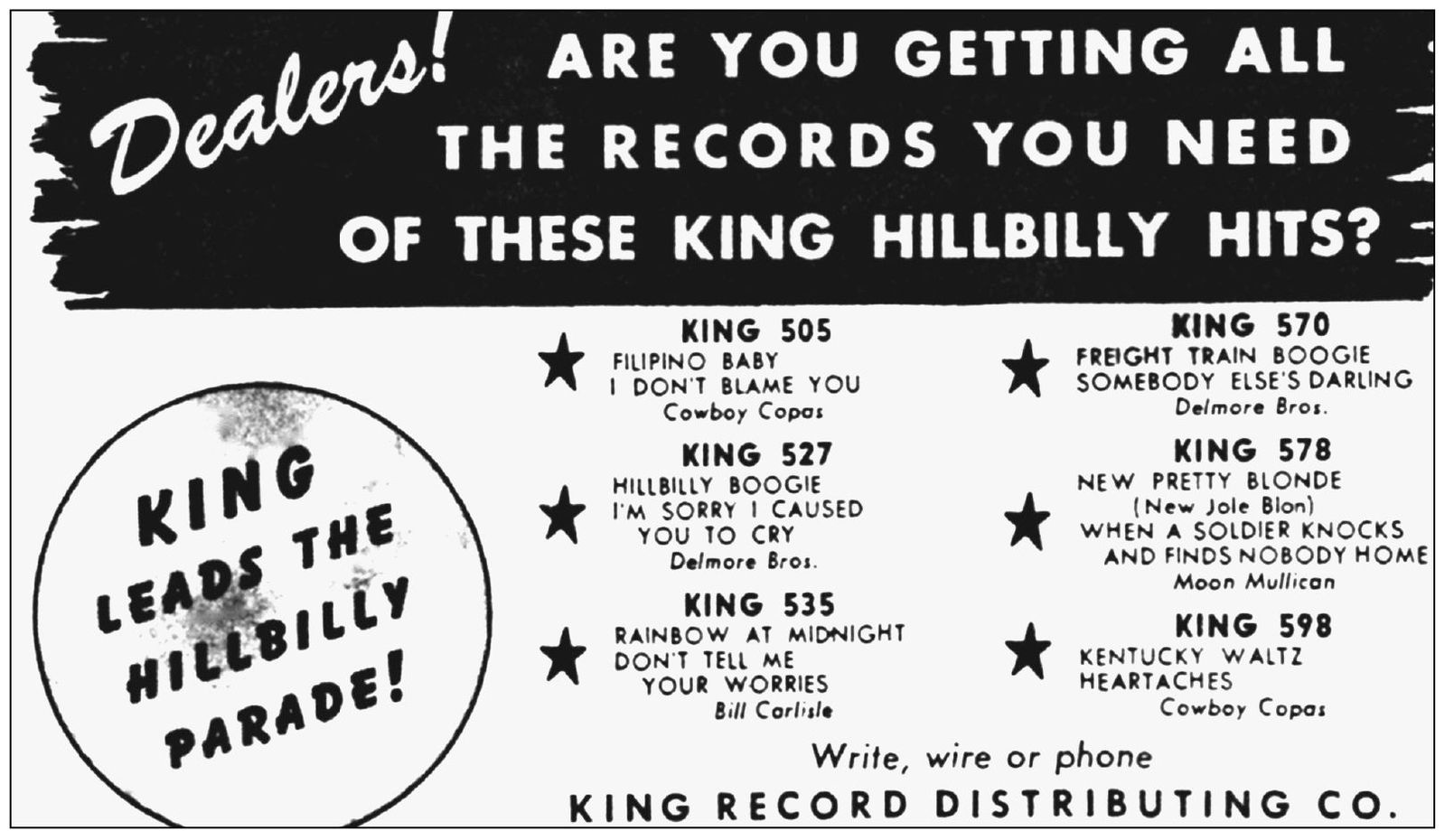

This c. 1946 advertisement promoted King’s hillbilly releases from a different address—1538 Brewster Avenue, Cincinnati 7, Ohio. The building in which King Records operated was actually several buildings, all connected. Apparently two of them used different street numbers. When the company finally took over most of the complex, it simplified the address to 1540. The “7” was a pre–zip code identification number. (Courtesy of Zella Nathan.)

Carolina Cotton, another early King Records country artist, hosted a program twice a week on the Armed Forces Radio Services in the late 1940s and early 1950s. She called herself the “Girl of the Golden West” and the “Queen of the Range.” Her show Carolina Cotton Calling entertained 90 million overseas listeners. She received more fan mail than any Hollywood star to appear on the Armed Forces Radio Services. (Author’s collection.)

In 1938, an announcer forgot the names of Henry D. Hayes and Kenneth C. Burns, who appeared on Chicago’s WLS Barndance and Don McNeil’s Breakfast Club. So the announcer called them Homer and Jethro. The name stuck. They recorded for King Records in 1947 and played on sessions. Their comic country act belied the fact that they were terrific musicians. They recorded “Donkey Serenade” and other humorous songs. (Author’s collection.)

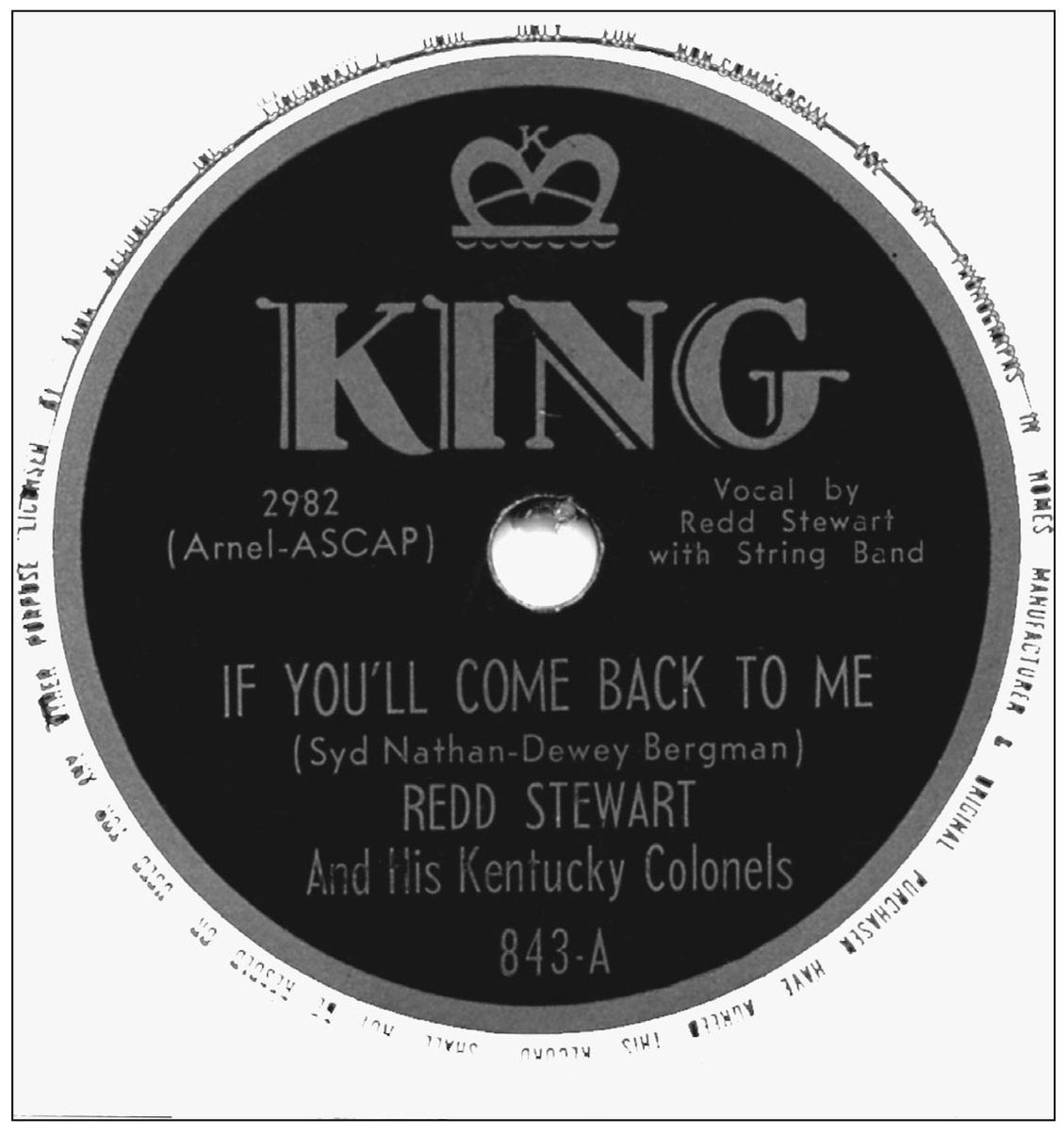

Pianist Henry “Redd” Stewart of Tennessee started performing in Pee Wee King’s Golden West Cowboys in 1940. They became songwriting partners, turning out hits such as “The Tennessee Waltz.” Stewart recorded a number of songs for King Records in the late 1940s and early 1950s. (Author’s collection.)

This picture shows that Stewart and his Kentucky Colonels recorded other people’s material. This song, “If You’ll Come Back To Me,” is credited to Syd Nathan and Dewey Bergman, King Records’ pop music director. Usually Nathan wrote under the pseudonym Lois Mann. He dabbled on the piano and thought of song ideas while walking through the halls of the King factory. “I write all the way down the line—from a pop tune to a hillbilly to a risqué, double entendre,” he once said. “I cover the field pretty well.” (Author’s collection.)

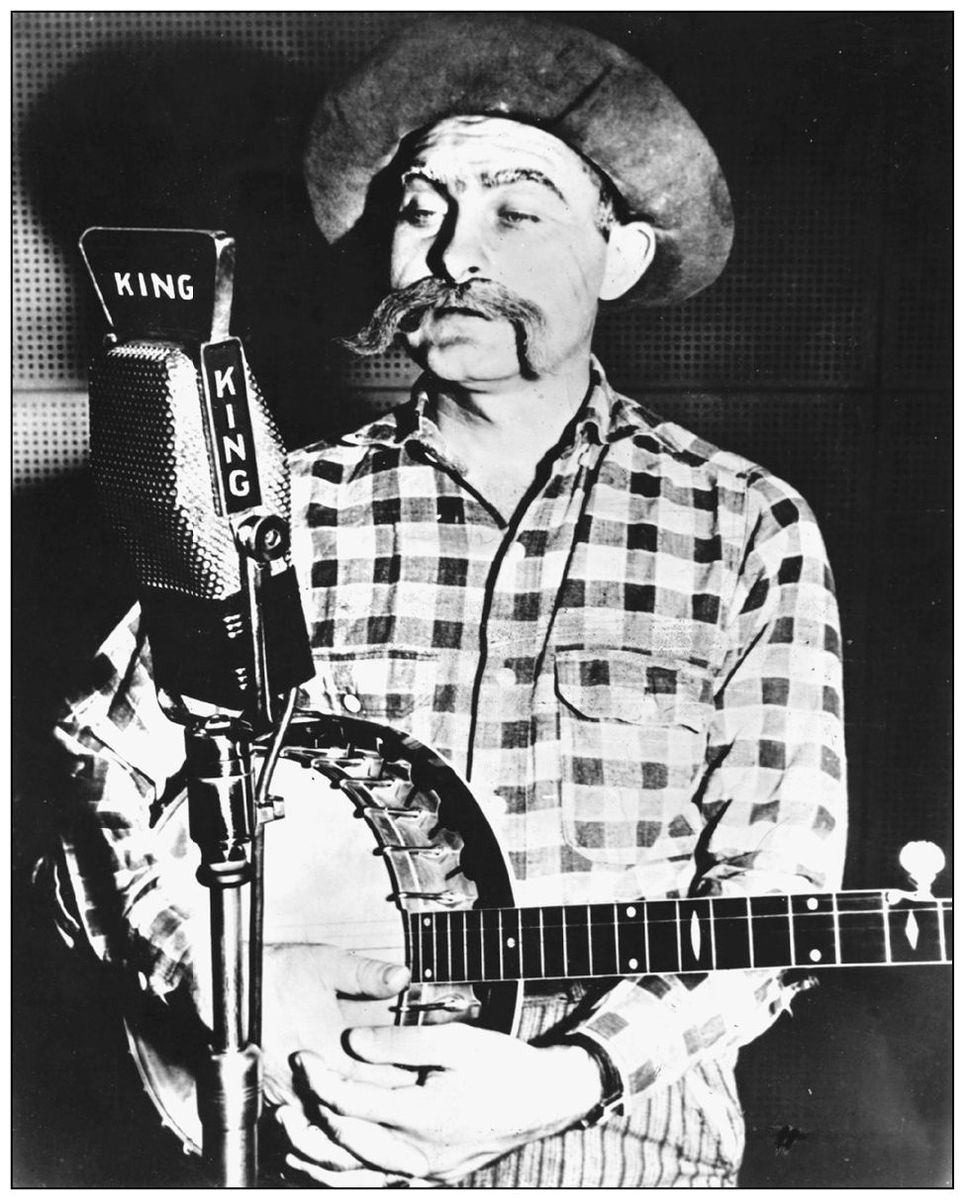

In November 1943, Grandpa Jones and fellow WLW sideman Merle Travis accompanied Nathan to Dayton, Ohio, to record Grandpa’s original “The Steppin’ Out Kind.” For King Records’ first release, Nathan billed the duo as the Shepherd Brothers. In this rarely seen photograph, Jones is performing out of character. People in Cincinnati probably did not recognize him when he walked near Crosley Square. (Author’s collection.)

Seen here, the original old-timer himself—singer, songwriter, and banjo player—poses in character next to a King Records microphone. After Grandpa Jones returned from World War II, he rejoined King and left WLW. “I just wanted to pick on a label,” he said. Nathan recorded him in Cincinnati, Hollywood, Chicago, and other cities. One of his more warmly received records was “It’s Raining Here This Morning.” (Author’s collection.)

West Virginian Charlie Gore started on WLW-T’s Midwestern Hayride in 1949 and became a regional country star. He recorded for King from 1951 to 1956, during which time he cowrote Bonnie Lou’s hit “Daddy-O.” Gore fit Syd Nathan’s idea of well-rounded talent—a country performer who could write commercially, play well, sing, and entertain. (Courtesy of Steve Lake.)

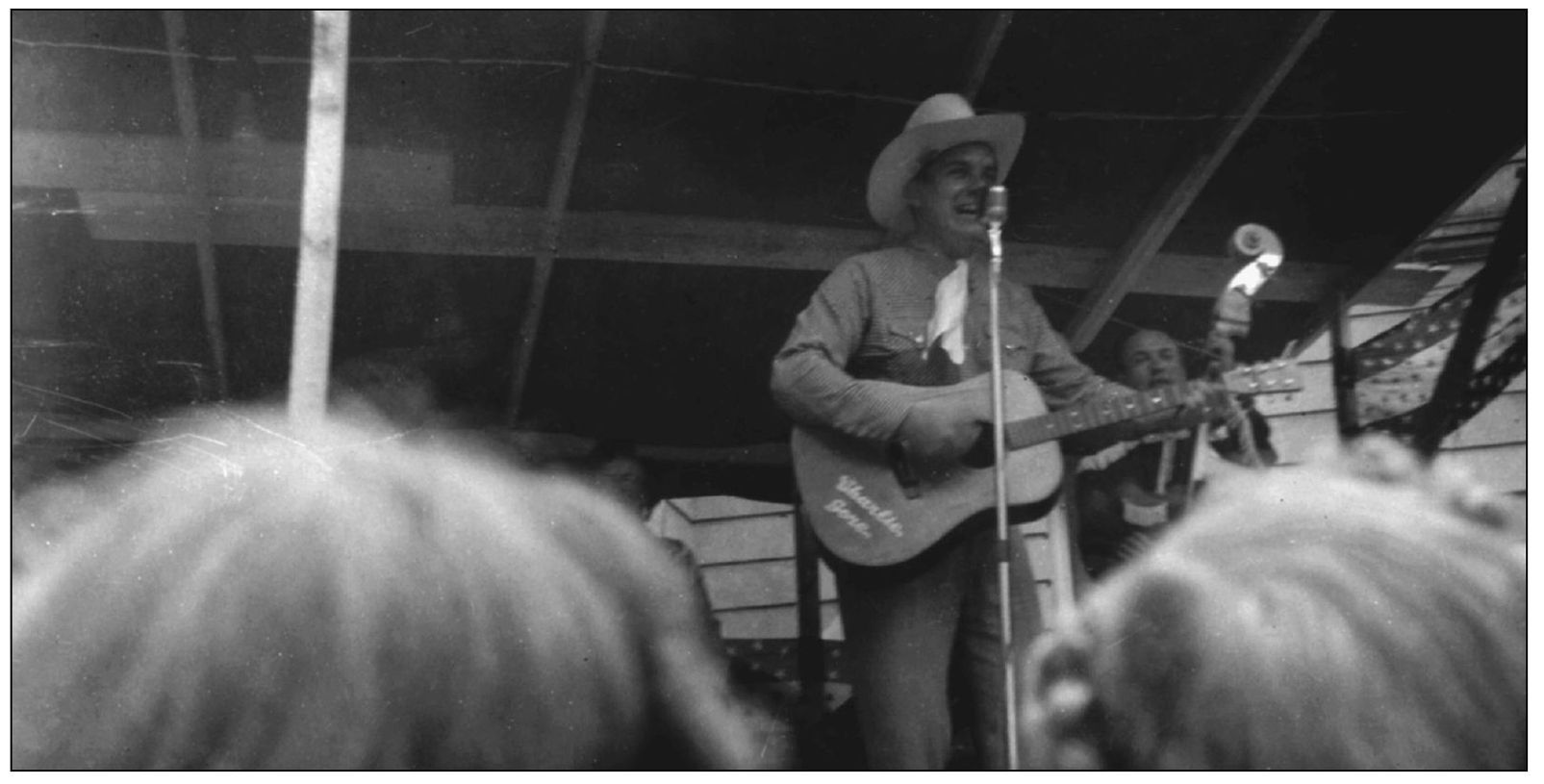

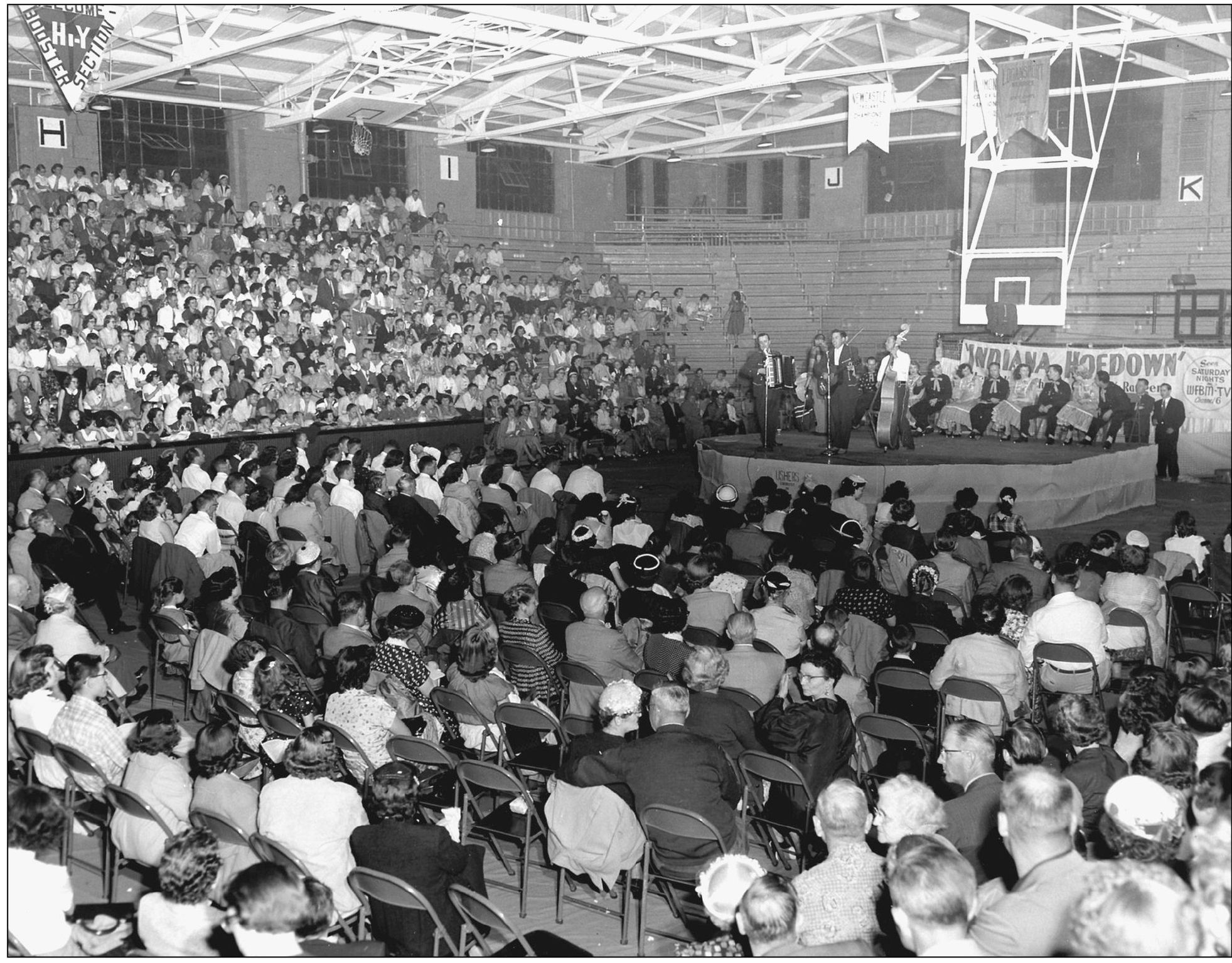

Gore and his band perform on a television benefit show in Indiana around 1956. He used no drummer, only a guitar, upright bass, fiddle, and accordion. In 1953, Gore left the Hayride to start the similar Indiana Hoedown in Indianapolis. He left that show in 1959 and retired from music. (Courtesy of Steve Lake.)

Gore sings as his band performs in a small-town Indiana school gymnasium around 1955. After coming out of retirement in 1960, he became a disc jockey for WVOW in Logan, West Virginia, and was elected to the state legislature for one term. He later returned to the Cincinnati area. He could not stay away from the crowds. In 1963, he opened a Columbus nightclub called the Frontier Ranch with Ray Stingley and later rejoined the Hayride in Cincinnati. By then the show was being broadcast in color and syndicated by ABC Films to 56 markets. When his television days ended, he remained in greater Cincinnati and served on the Butler County Board of Elections. (Courtesy of Steve Lake.)

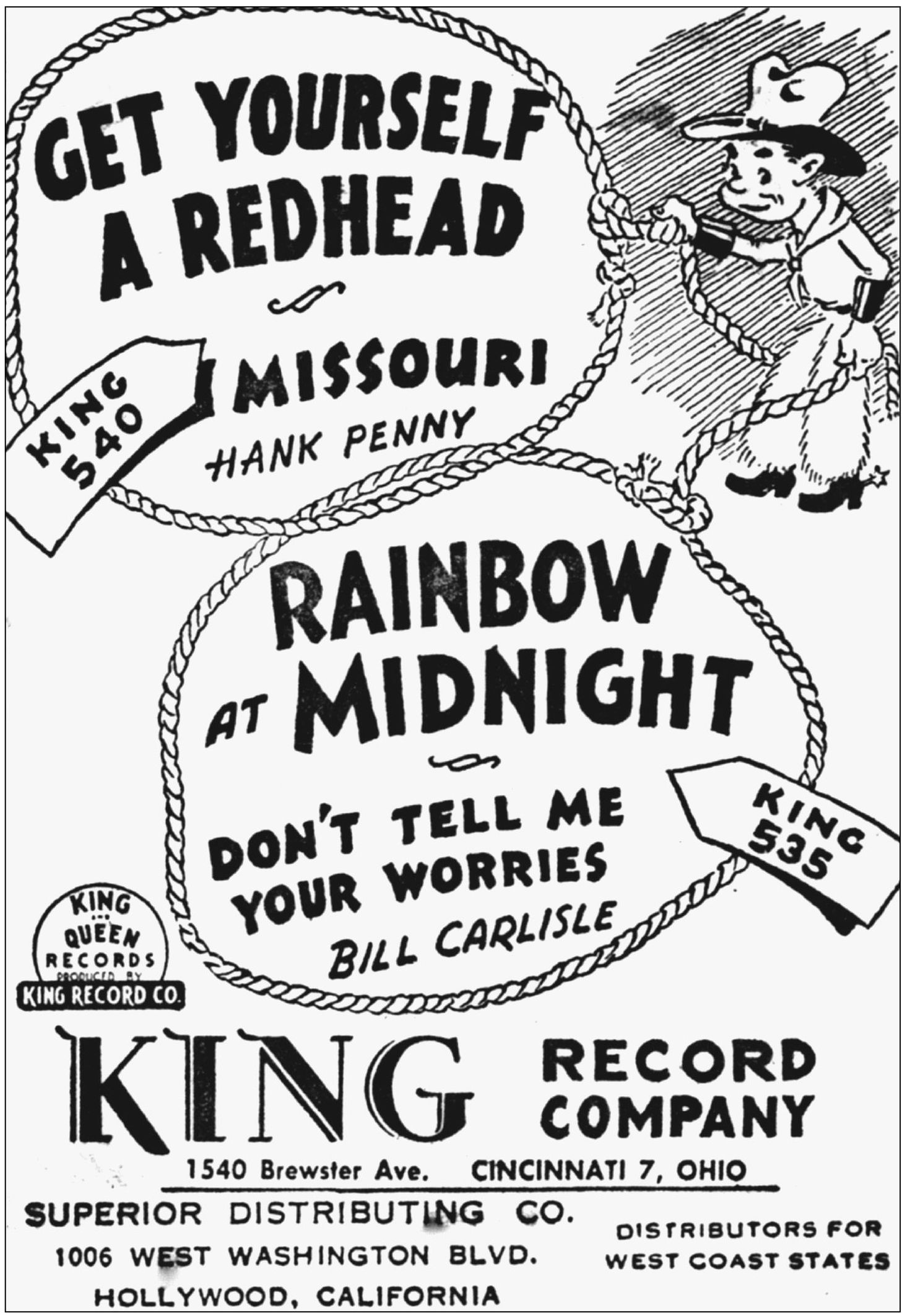

King Records owed its early successes to three major things—proper timing (the postwar market needed new country acts); talented performers, writers, and executives; and sufficient trade advertising. This advertisement from around 1946 promotes two performers whose music sounds good to this day—Hank Penny and Bill Carlisle. Penny cut many songs with novelty titles, and Carlisle followed his hit “Rainbow at Midnight” with his own 1947 answer record, “Answer to Rainbow at Midnight.” (Courtesy of Zella Nathan.)

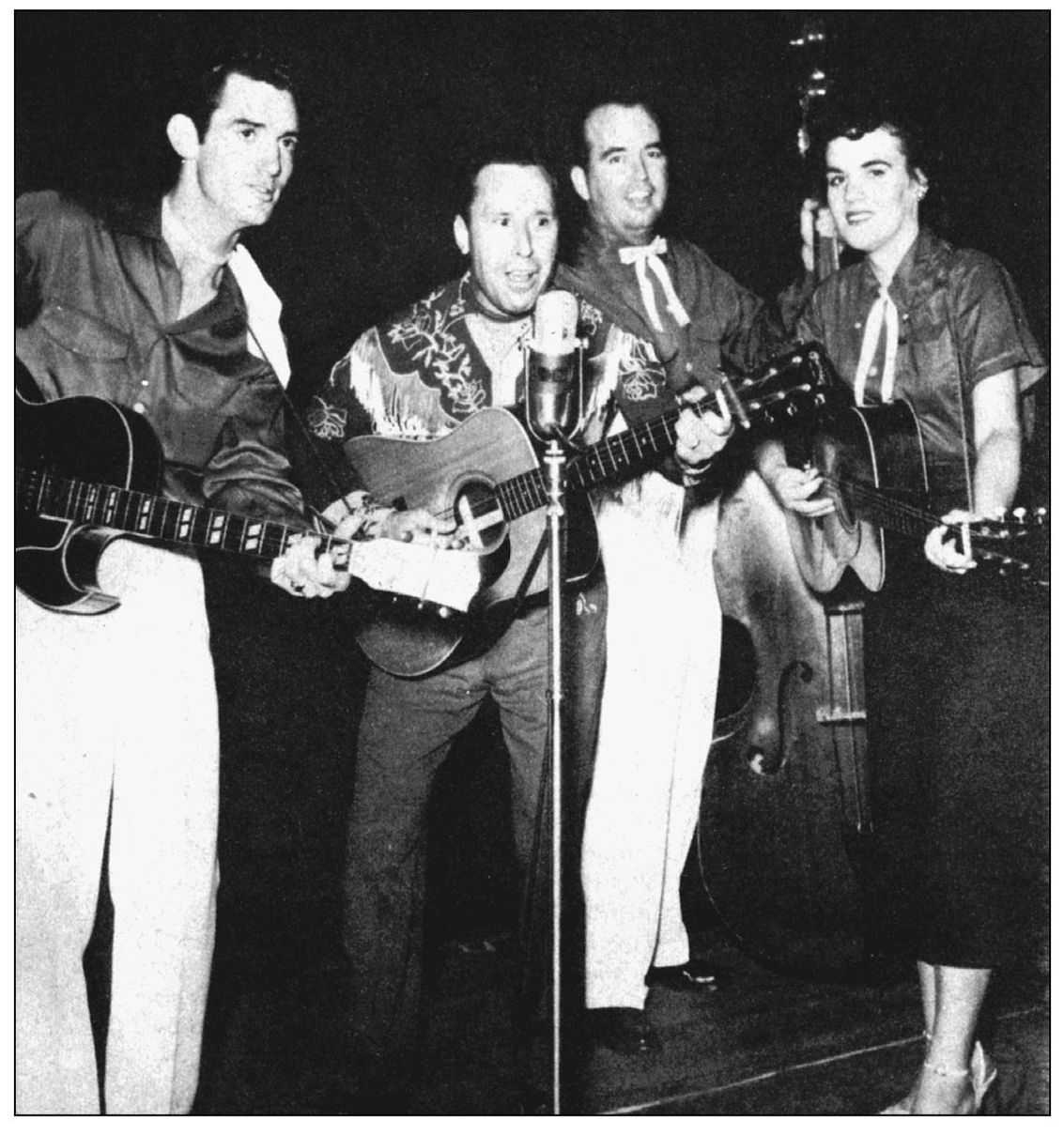

Bill Carlisle (at the microphone) was born in Wakefield, Kentucky, in 1908. He came from a musical family; brother Cliff became a country star and Bill led the Carlisles with sister Betty. As a child, Bill taught himself to play guitar. In 1931, he started in Louisville radio, and two years later he was recording in New York. He joined King Records in the mid-1940s. (Author’s collection.)

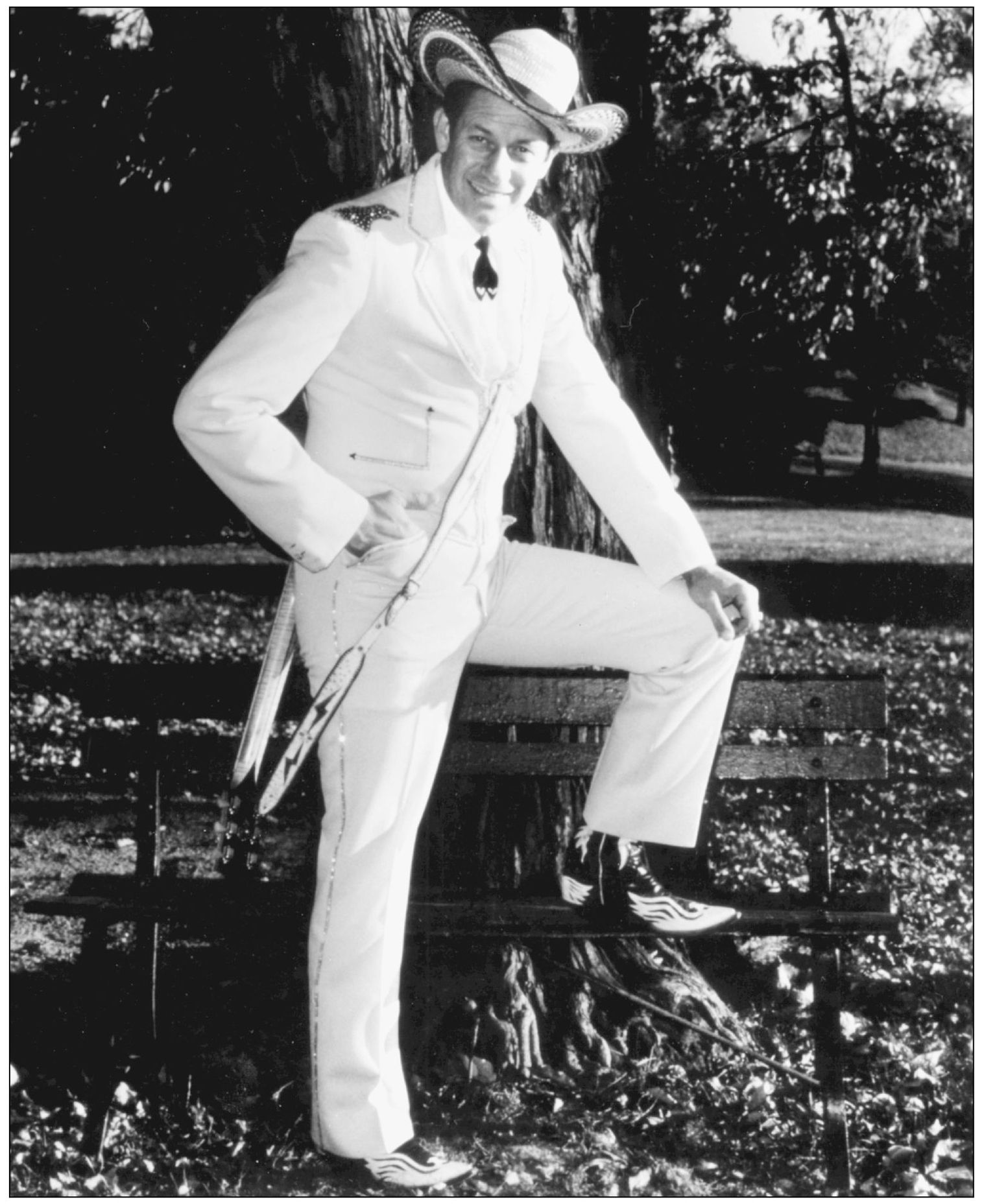

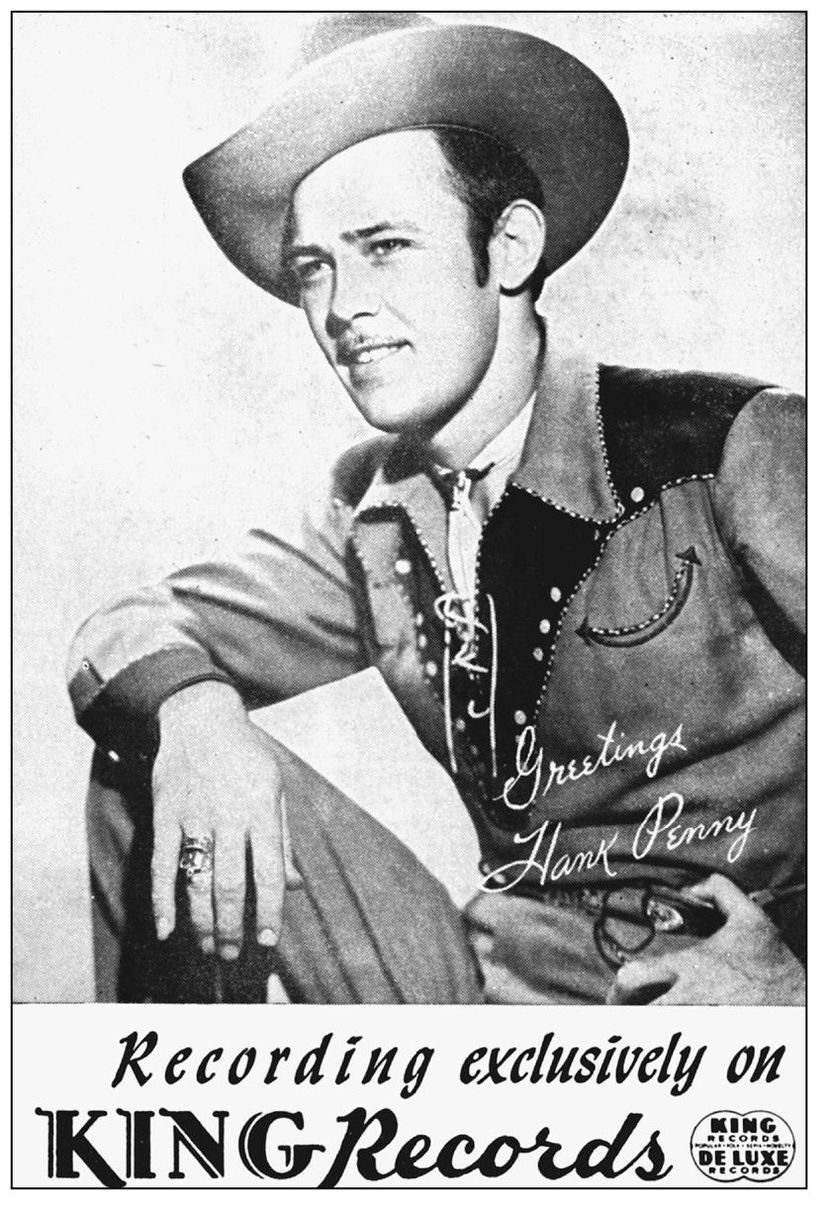

After Hank Penny became a popular Cincinnati radio performer, he moved to California in 1945 and cultivated a new audience with his band, the California Cowhands. The Birmingham native often dressed in a cowboy suit decorated with shiny pennies for buttons. For King Records, he recorded songs such as “Bloodshot Eyes” and “Won’t You Ride In My Little Red Wagon.” (Author’s collection.)

Curly Fox—born Arnim Le Roy in Dayton, Tennessee—and his wife, “Texas Ruby” Owens, performed on radio stations across the country, including WLW. They started recording for King Records in the late 1940s. Later the company issued albums by the duo with themes such as railroad songs, Nashville songs, and square dance songs without calls. (Author’s collection.)

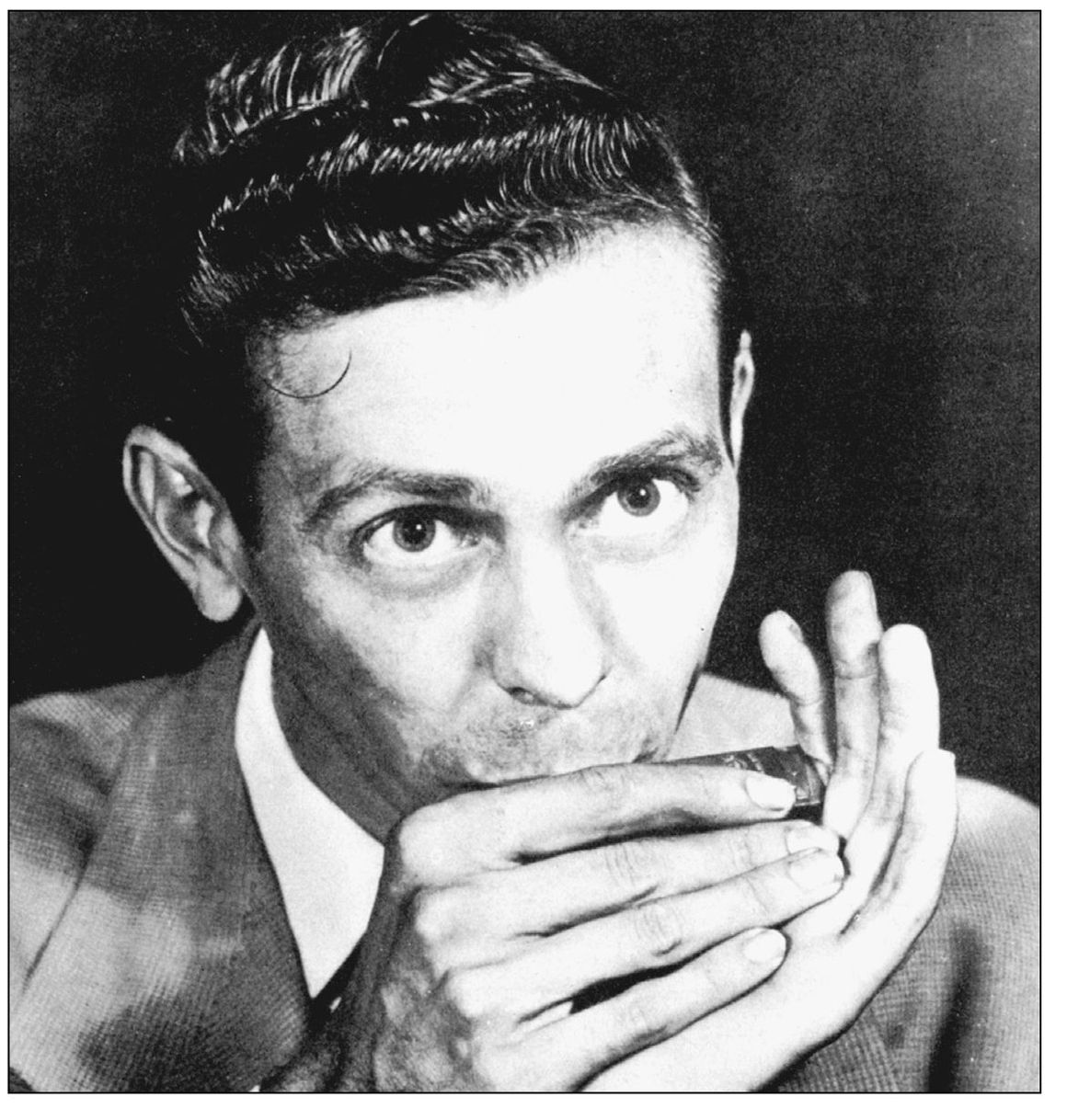

Wayne Raney became one of King Records’ top session players, songwriters, and artists of the late 1940s. The native of Wolf Bayou, Arkansas, started playing harmonica as a child. He hitchhiked across the country until a radio station manager hired Raney to perform on a program. In Cincinnati, he hosted the Jamboree on WCKY. His biggest King hit was “Why Don’t You Haul Off and Love Me,” in 1949. (Author’s collection.)