Four

JAMES BROWN, R&B, AND JAZZ

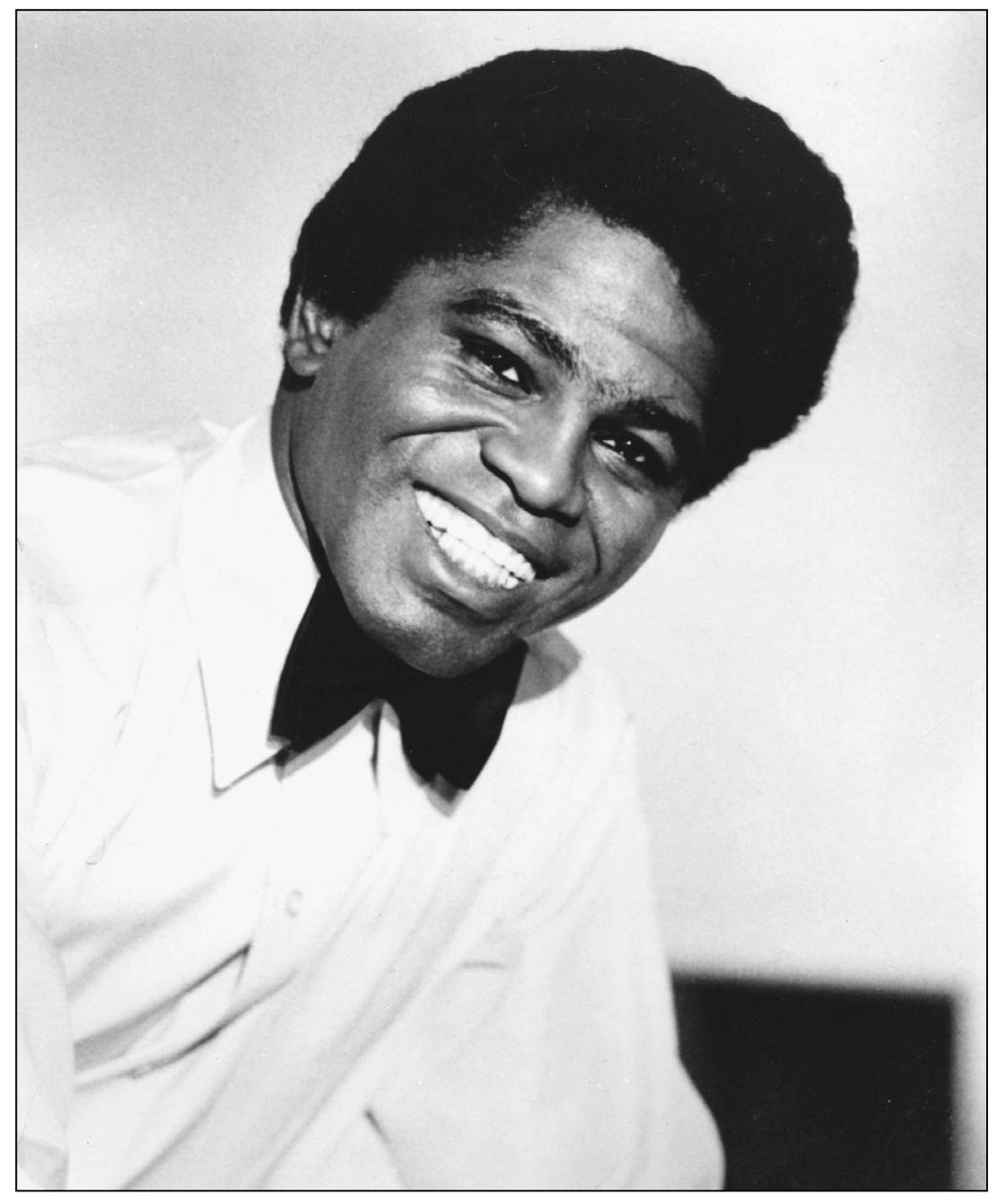

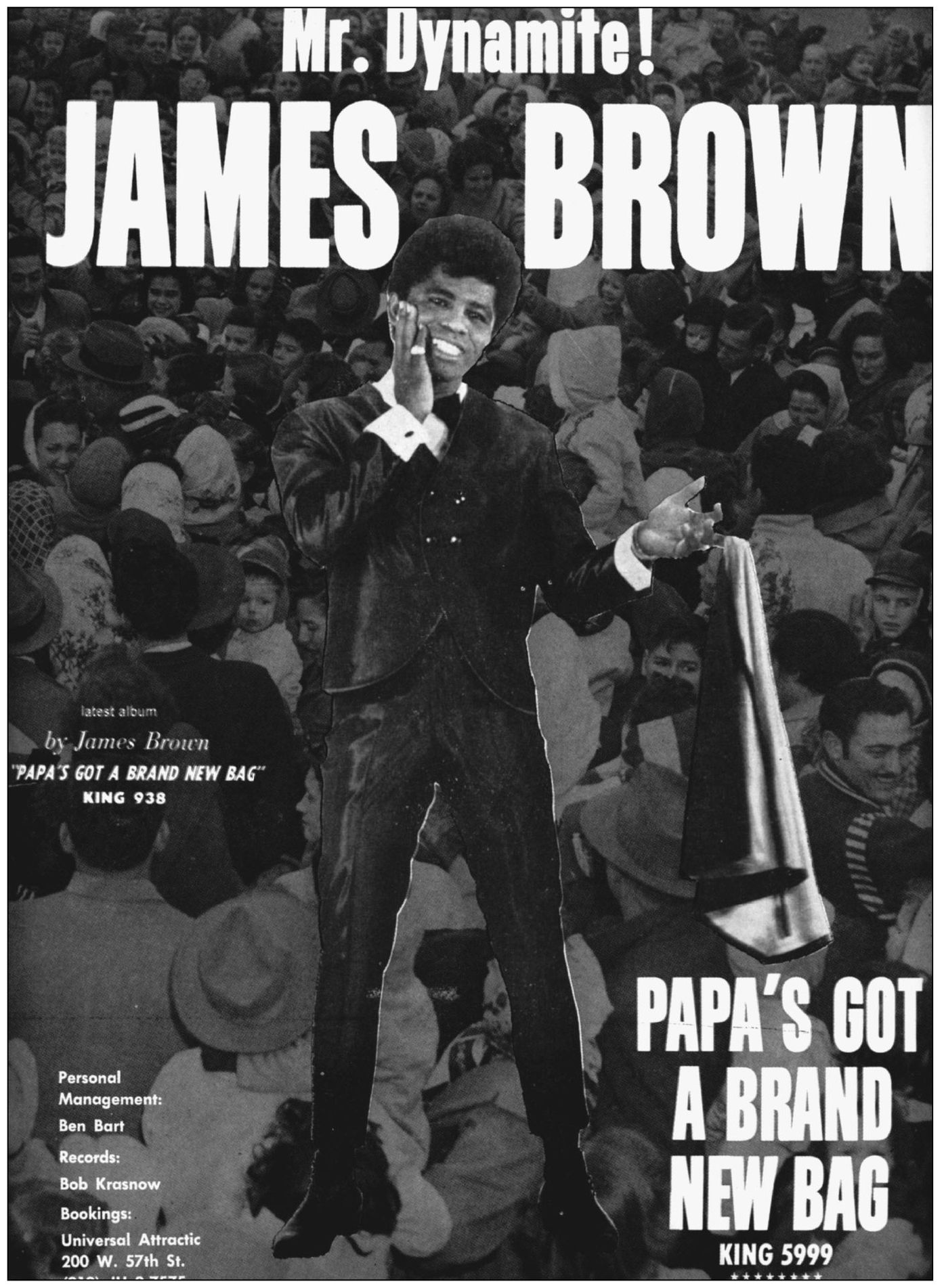

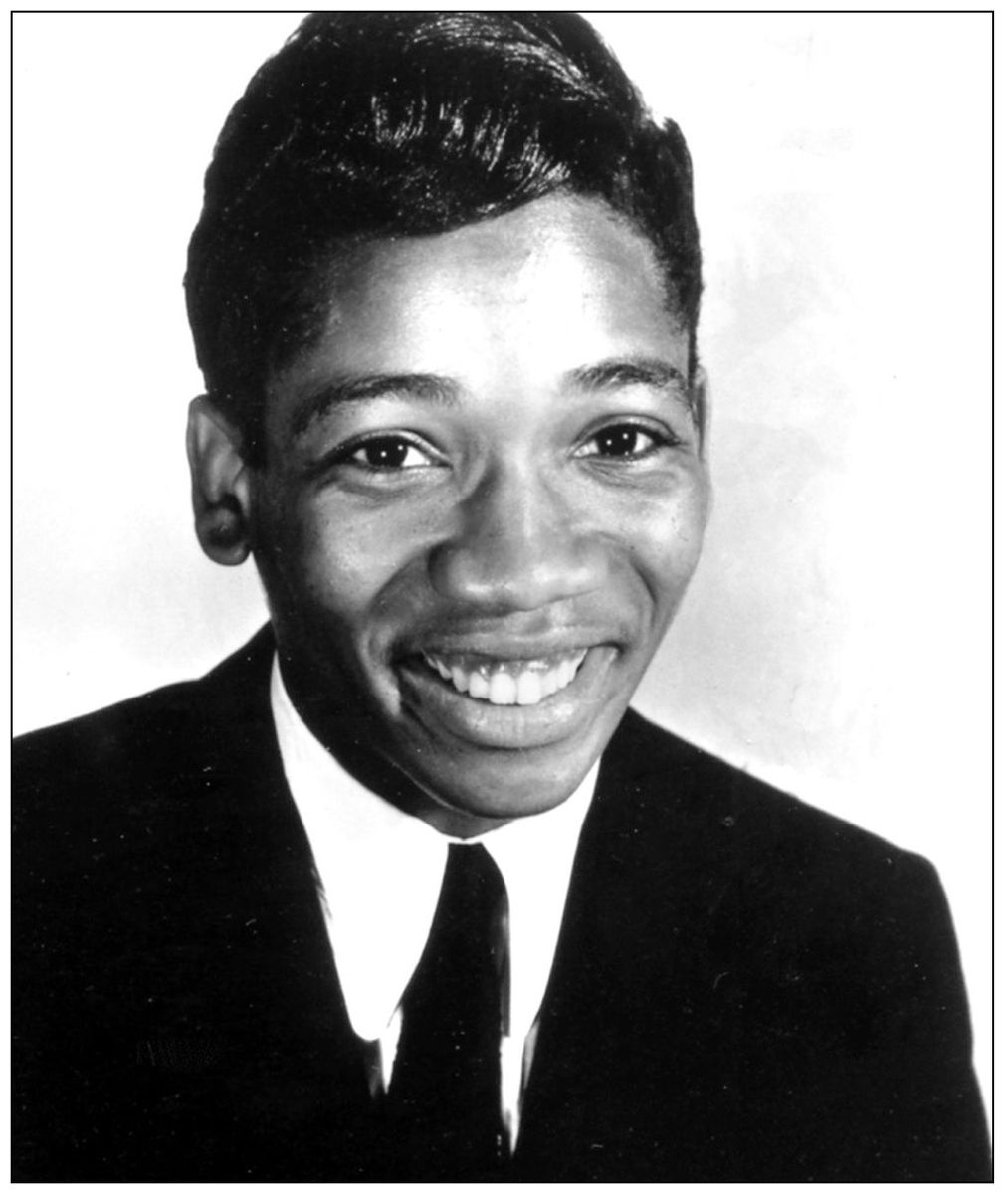

James Brown smiles in this c. 1967 photograph, and he should. By then, he was carrying King Records on his muscular shoulders, and his major struggles with owners were history. “Soul Brother No. 1” would soon produce music for his own King Records–distributed labels. (Author’s collection.)

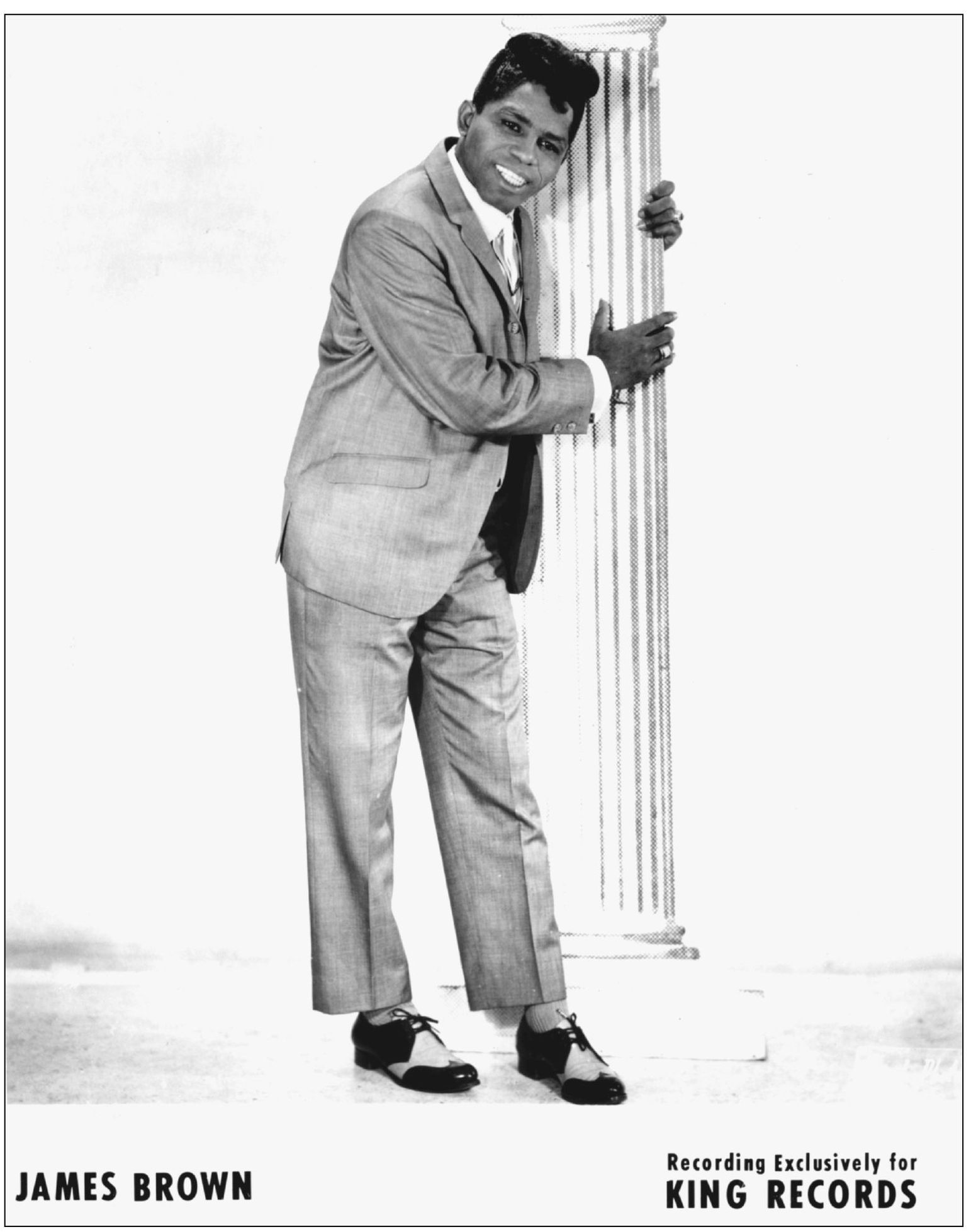

In the King Records’ studio on February 6, 1956, James Brown and the Famous Flames recorded four songs, including his original “Please, Please, Please.” It was mostly a moaning repetition of the three words—ghastly and foreign sounds to the ears of traditionalist Sydney Nathan, a genuine hook line admirer. “What in the hell are they doing?” he yelled in the control room. “That doesn’t sound right to my ears.” One can only imagine how Brown’s guttural sounds grated on Nathan’s weary soul that day. After spewing a few profanities, he reportedly told Brown and producer Ralph Bass, “Nobody wants to hear that noise.” To Nathan’s surprise, however, the record hit big. Suddenly Brown and the group had gained a reprieve at King’s Federal Records subsidiary, operated by Bass. He knew his job was secure as long as the hits kept coming. (Author’s collection.)

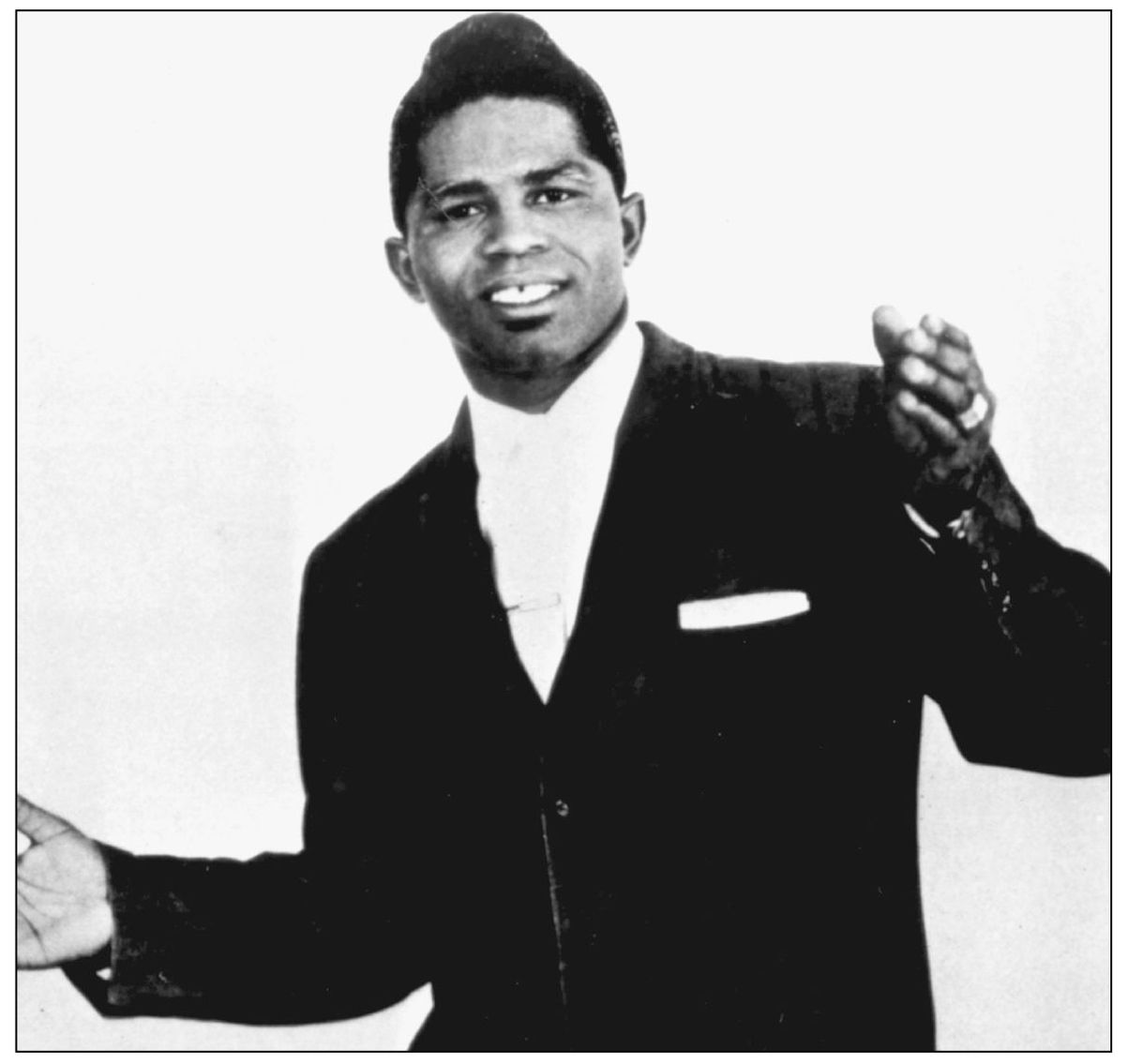

At times, Brown reached out to Nathan, and their often-contentious relationship went smoothly—for a time. Finally, after Brown proved that he could consistently sell millions of records, Nathan realized that it was futile to restrain such a popular act in the studio. From 1966 until 1968, the two patched their cracked relationship. (Author’s collection.)

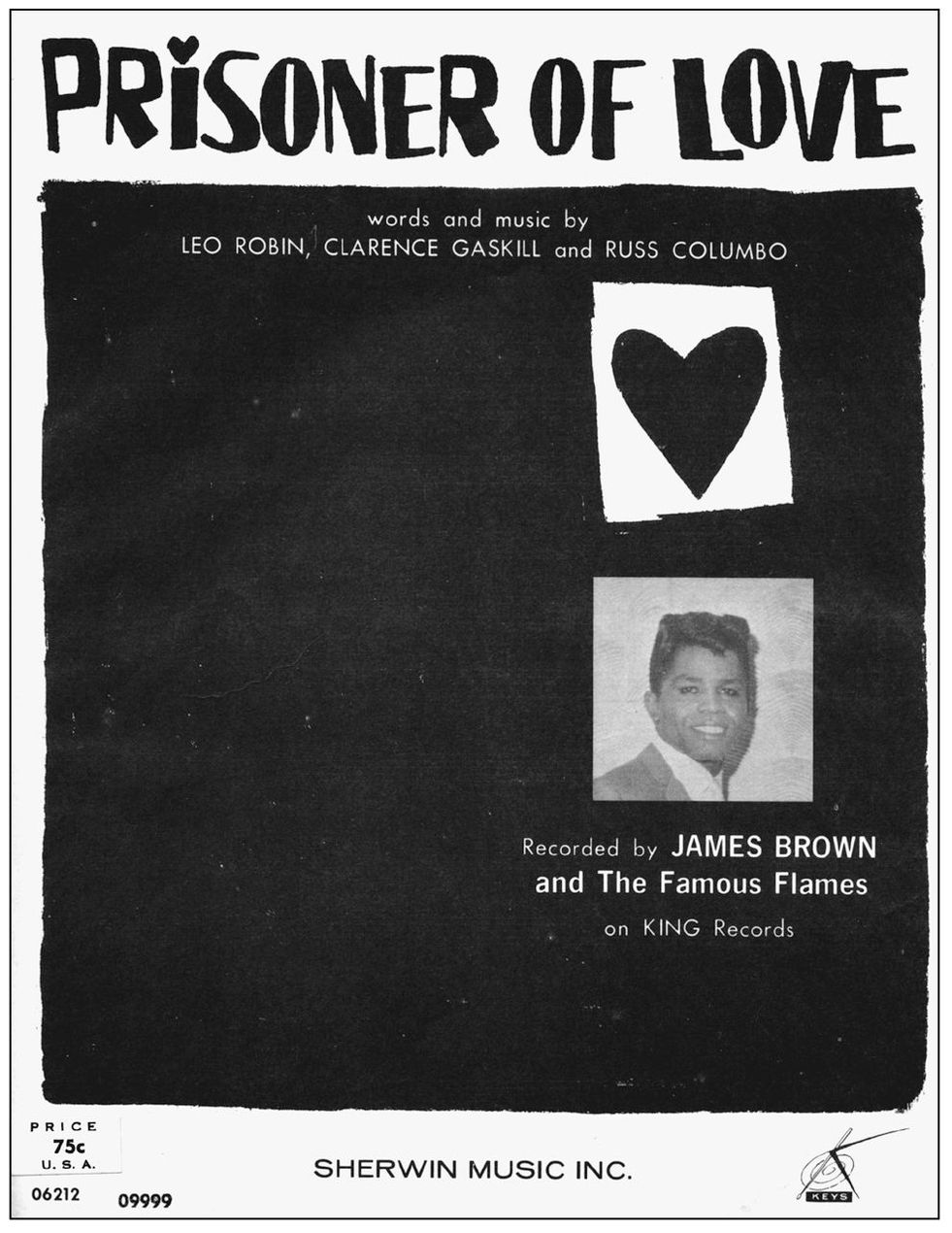

After four modest sellers, in the spring of 1963 James Brown turned to an old pop ballad, “Prisoner of Love,” which returned him to the R&B charts as well as the pop. The New York track balanced Brown’s soulful moaning against Sammy Lowe’s lush string arrangements. No doubt Nathan was pleased. Finally his style of song had been recorded by his top act. (Author’s collection.)

In June 1965, Brown’s pioneer funk single for King Records, “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” reached the top 10 in R&B and pop. He and his band recorded it in an unlikely place—Arthur Smith’s studio in Charlotte, North Carolina. Perhaps the site was chosen for convenience or to avoid anticipated criticism from King Records management. Smith, a veteran country musician, knew how to set up a studio. “It took only four tracks,” Smith said of the “Papa” session, “because that’s all we had. But the band was ready.” The record’s infectious dance beat and odd lyrics intrigued young listeners. Despite the limited number of tracks available, the recording’s high level of clarity—and its musicianship—is still obvious. Many record buyers could not understand all the words on the hot new record, but they did appreciate Brown’s electric performance. A year later, he and his band returned to Smith’s studio to cut their hit “Don’t Be a Drop-Out.” (Author’s collection.)

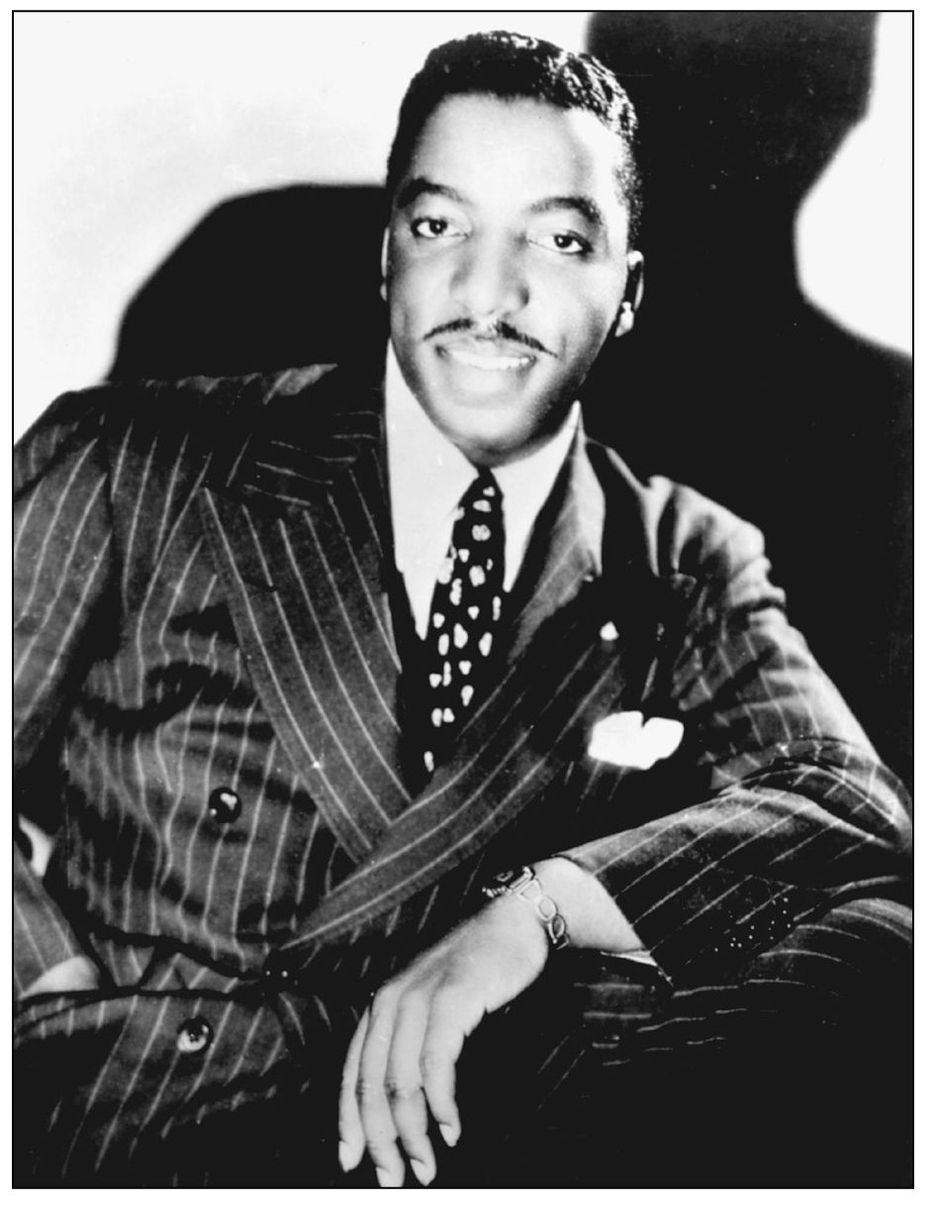

Erskine Hawkins recorded “Walkin’ by the River,” “The Way You Look Tonight,” and other songs in New York in September 1952. The jazz artist would go on to carve out a career for himself in the field. He was one of a number of black jazz artists, including Roland Kirk, to record for King Records. (Author’s collection.)

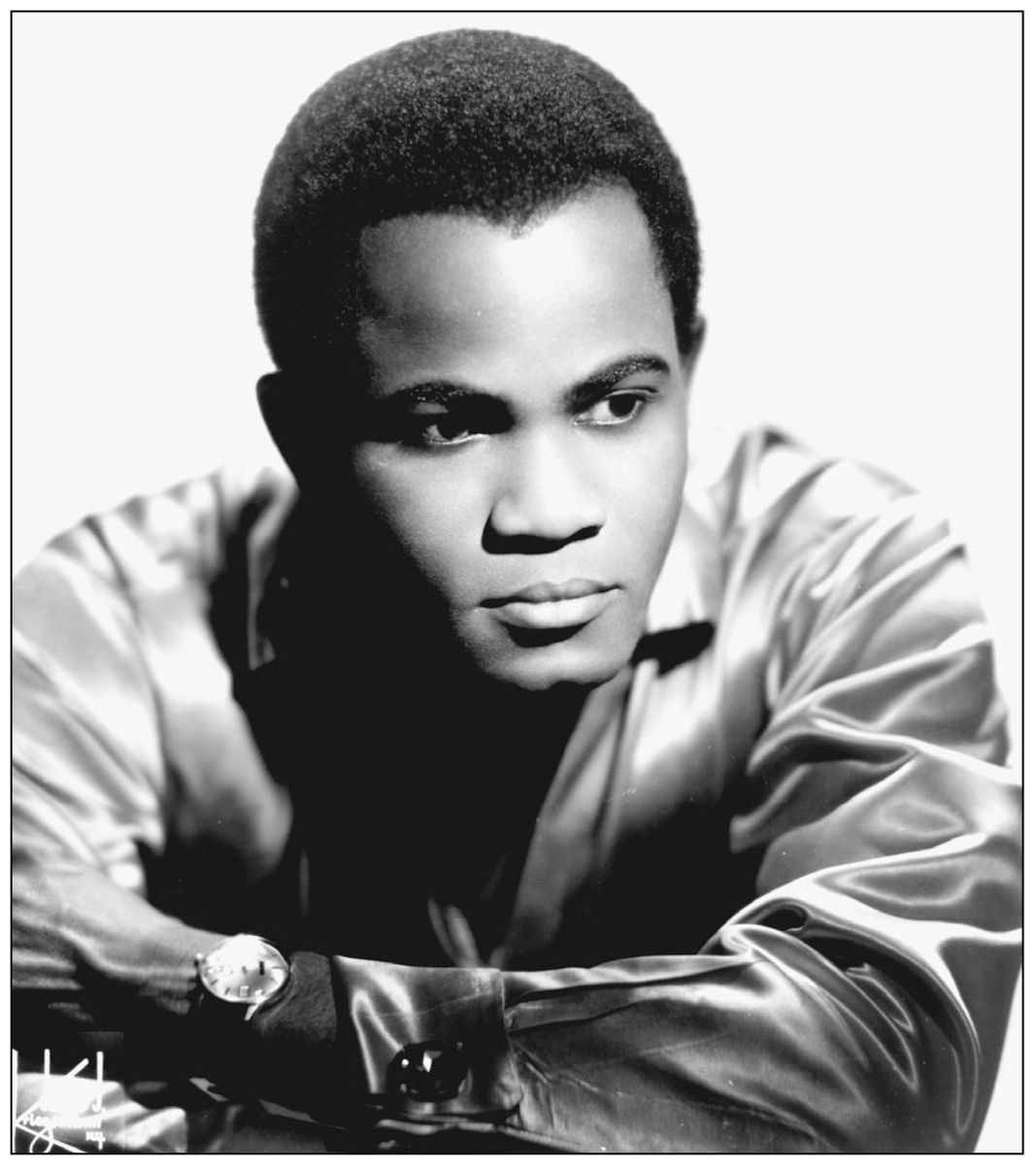

Like many other talented performers, singer-songwriter Joe Tex came to King Records before his time. In New York in 1955, he recorded “Come in this House” for the company, but he did not have the first of his many hits until 10 years later on the Nashville-based Dial label. He is known for “Hold What You Got” and “Skinny Legs and All.” (Author’s collection.)

During a slow period in the early 1960s, King Records started distributing Beltone and other independent record labels, which was odd, because King Records was never known for its lightning-quick distribution. Nevertheless, the new labels generated interest and helped bring much-needed hits to King Records. Indianapolis native Bobby Lewis, who had recorded for the Parrot label as early as 1952, cut two big R&B and pop hits, “Tossin’ and Turnin’ ” and “One Track Mind” for Beltone in 1961. (Author’s collection.)

Lewis’s hits brought King Records to the attention of rock disc jockeys across the nation. (Author’s collection.)

The Platters, a smooth doo-wop group, started recording for Federal Records in 1954. The group cut “Only You,” written by manager Buck Ram, but the record was not released, at least not in time to suit Ram. He moved his group to Mercury in 1955, reorganized its personnel and rerecorded “Only You” with lead Tony Williams. It became the first of 14 Platters hits through early 1960. (Author’s collection.)

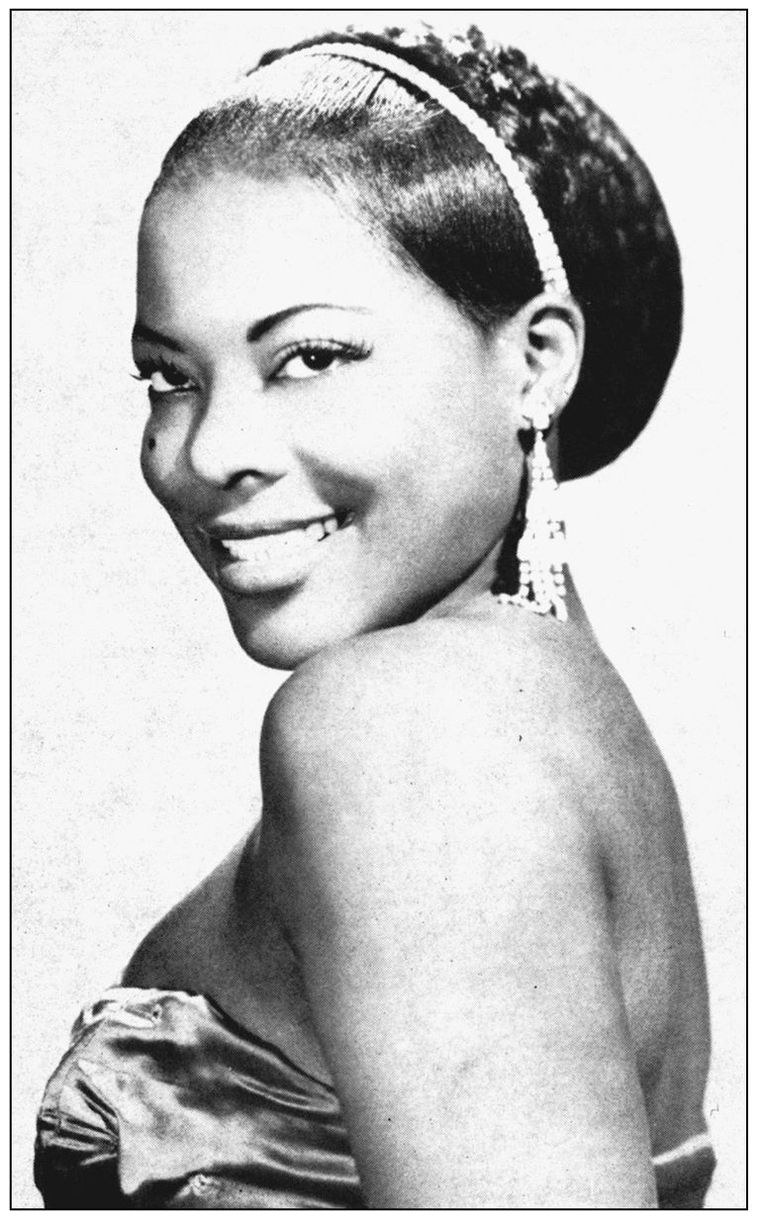

Lavern Baker, born Delores Williams in Chicago in 1929, performed with the Todd Rhodes Orchestra in 1952 and sang lead on “Trying” and three other King Records singles. By 1955, she had signed with Atlantic. She hit with “Tweedle Dee” and other songs through 1966, becoming yet another major R&B star who got away from King Records. (Author’s collection.)

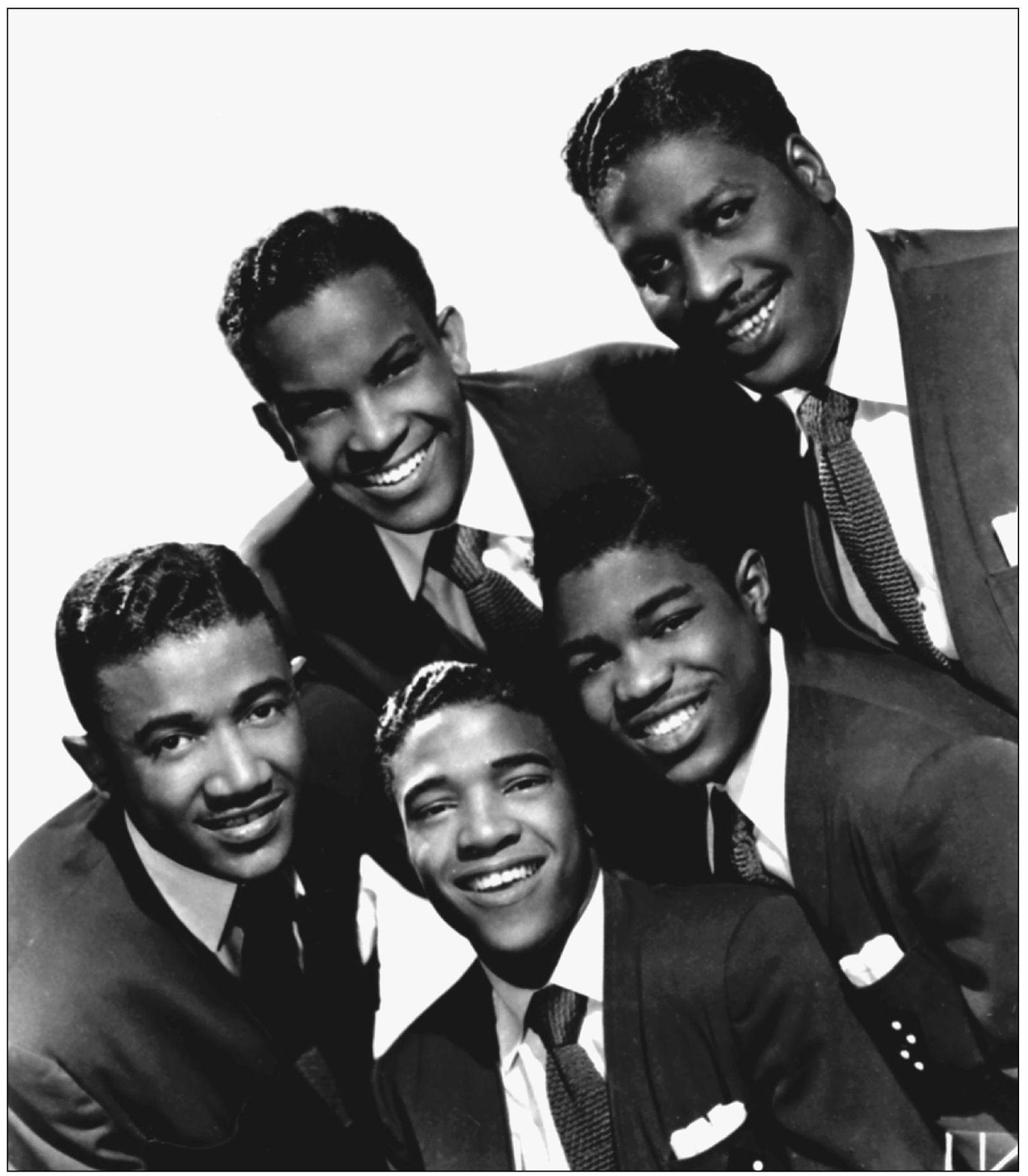

In 1950, Billy Ward formed the Dominoes in New York. Originally called the Ques, they were (in no particular order): Clyde McPhatter, lead vocals; Charles White, tenor; Bill Brown, bass; Joe Lamont, baritone; and Ward, piano. Ward signed with King Records that year, and the hits—10 altogether—began. Their second was one of King Records’ double entendre songs called “Sixty-Minute Man,” a highly suggestive song that would be covered and remade by many artists. McPhatter sang with Ward from 1950 to 1953. Jackie Wilson joined in 1953 and left in 1957. (Author’s collection.)

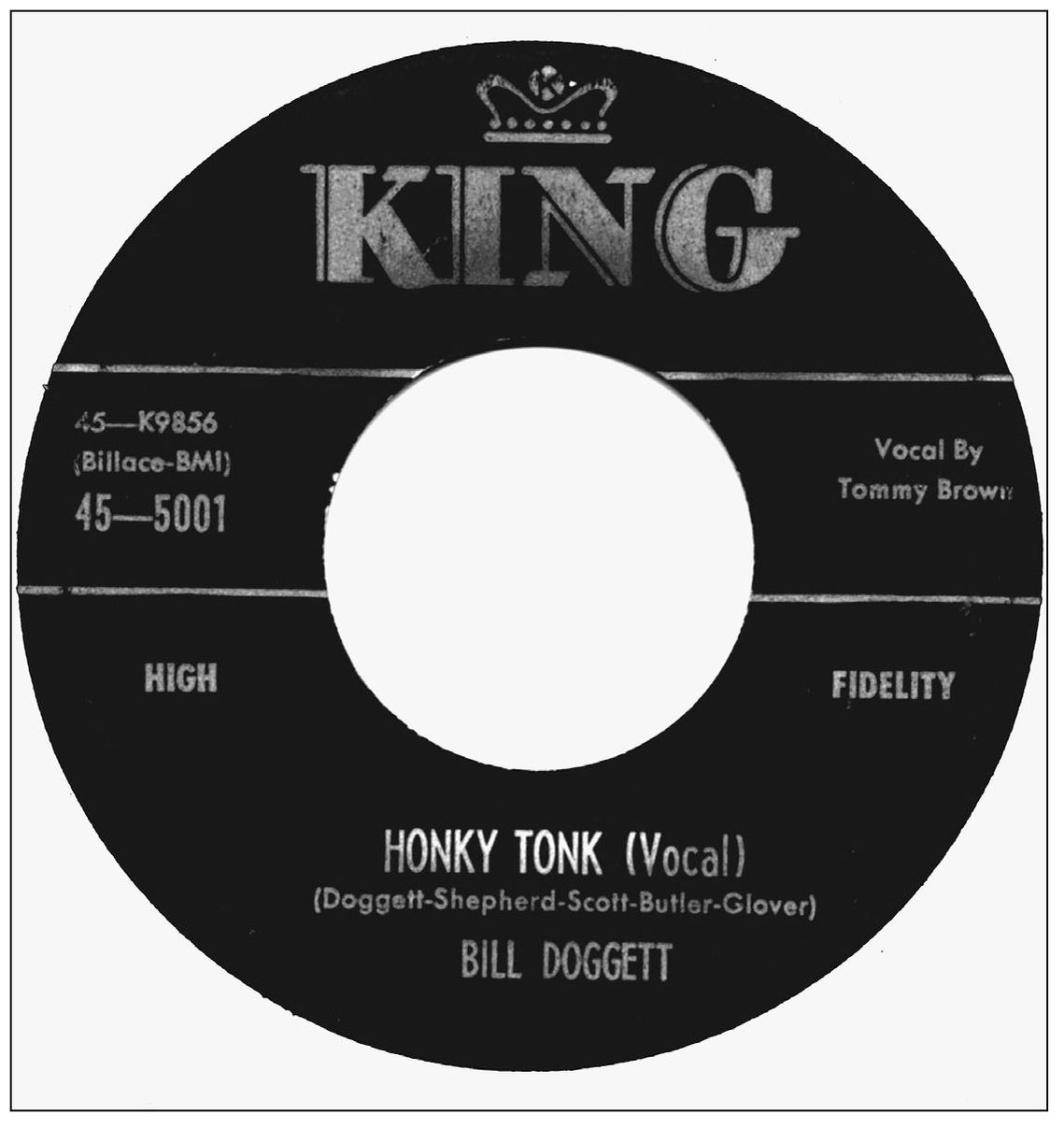

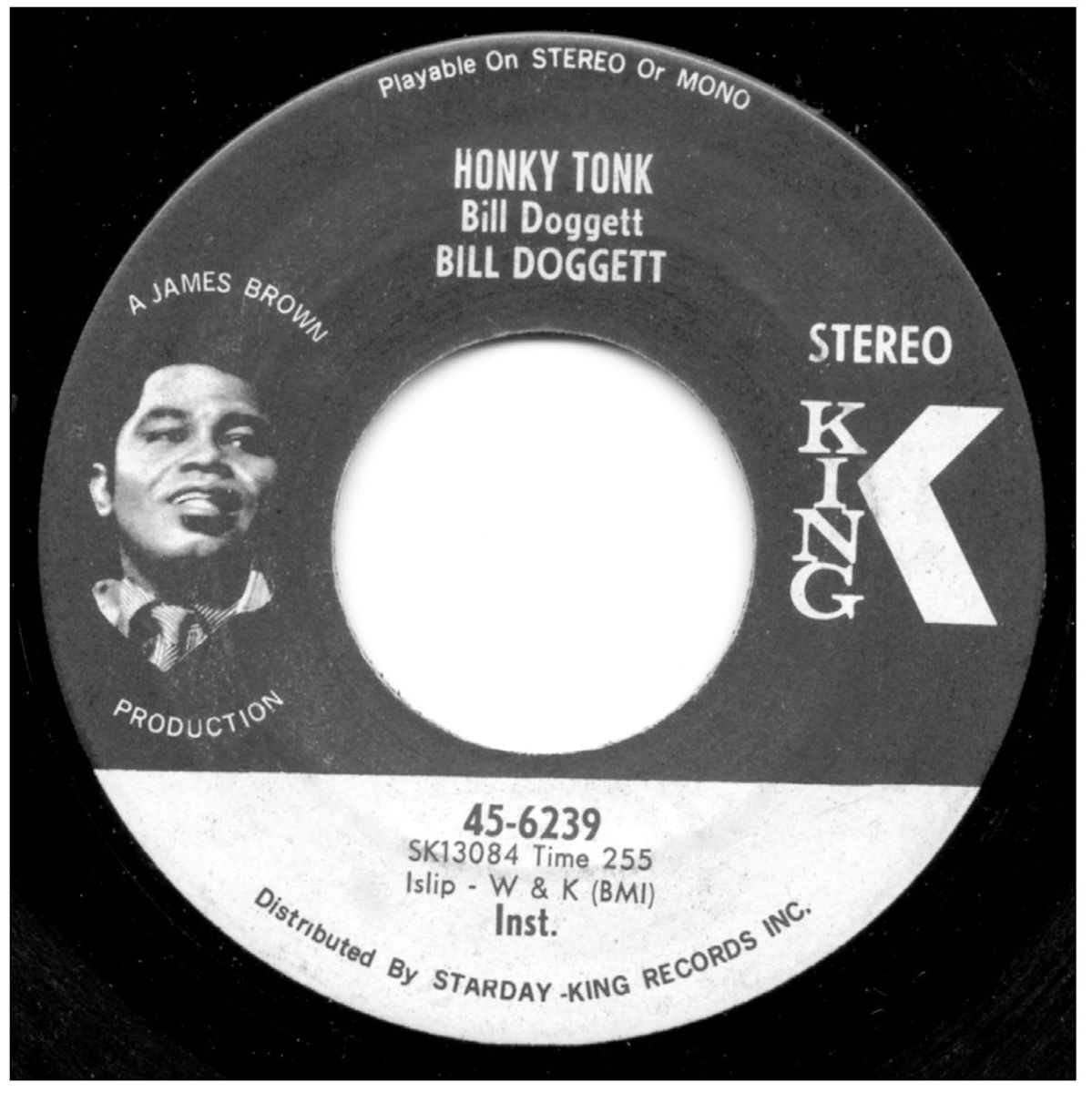

In 1956, organist Bill Doggett liked a melody his band had created during a jam session. Soon a whole instrumental emerged, and the group recorded it in New York. “Honky Tonk (Parts I and II)” prominently featured Clifford Scott on sax, unlike most other Doggett recordings. The single became a huge R&B and pop hit that year. To maximize profits on the song, King asked Doggett to record a vocal version under his name with singer Tommy Brown. The hit helped make Doggett a major player in King Records’ stable of instrumentalists. He was well represented on singles and albums, and “Honky Tonk” went on to influence a younger generation of musicians, including Cincinnati guitarist Lonnie Mack, who would record his guitar version for Fraternity Records. (Author’s collection.)

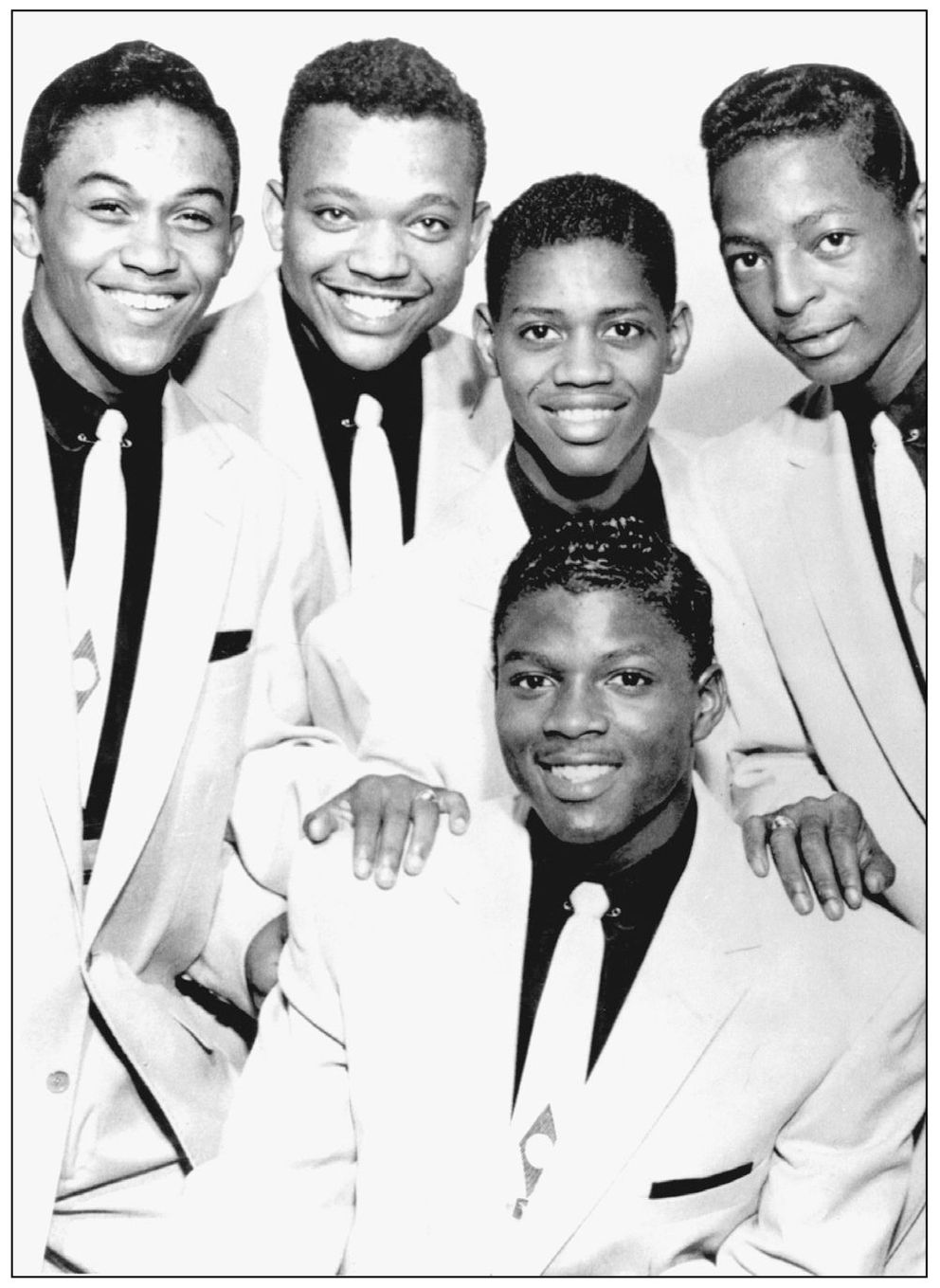

A King Records talent scout discovered Otis Williams at a performance at Withrow High School. Williams and fellow students formed the Charms, an early doo-wop group. Their first hit, “Hearts of Stone,” reached No. 1 on Billboard’s R&B chart in the fall of 1954 for King’s DeLuxe Records. But Williams almost did not go into music. He was offered a football scholarship at the Ohio State University and a contract with the Cincinnati Reds. Music called, however, and soon the hits followed. After reorganizing in 1956, the group became Otis Williams and the Charms, and they hit with “That’s Your Mistake,” “Ivory Tower,” and “United.” Today Williams continues to perform and live in Cincinnati. In the c. 1956 photograph at left, group members are, from left to right, Lonnie Carter, Matthew Williams, Rollie Willis, Winfred Gerald, and Otis Williams in the middle. (Courtesy of Otis Williams.)

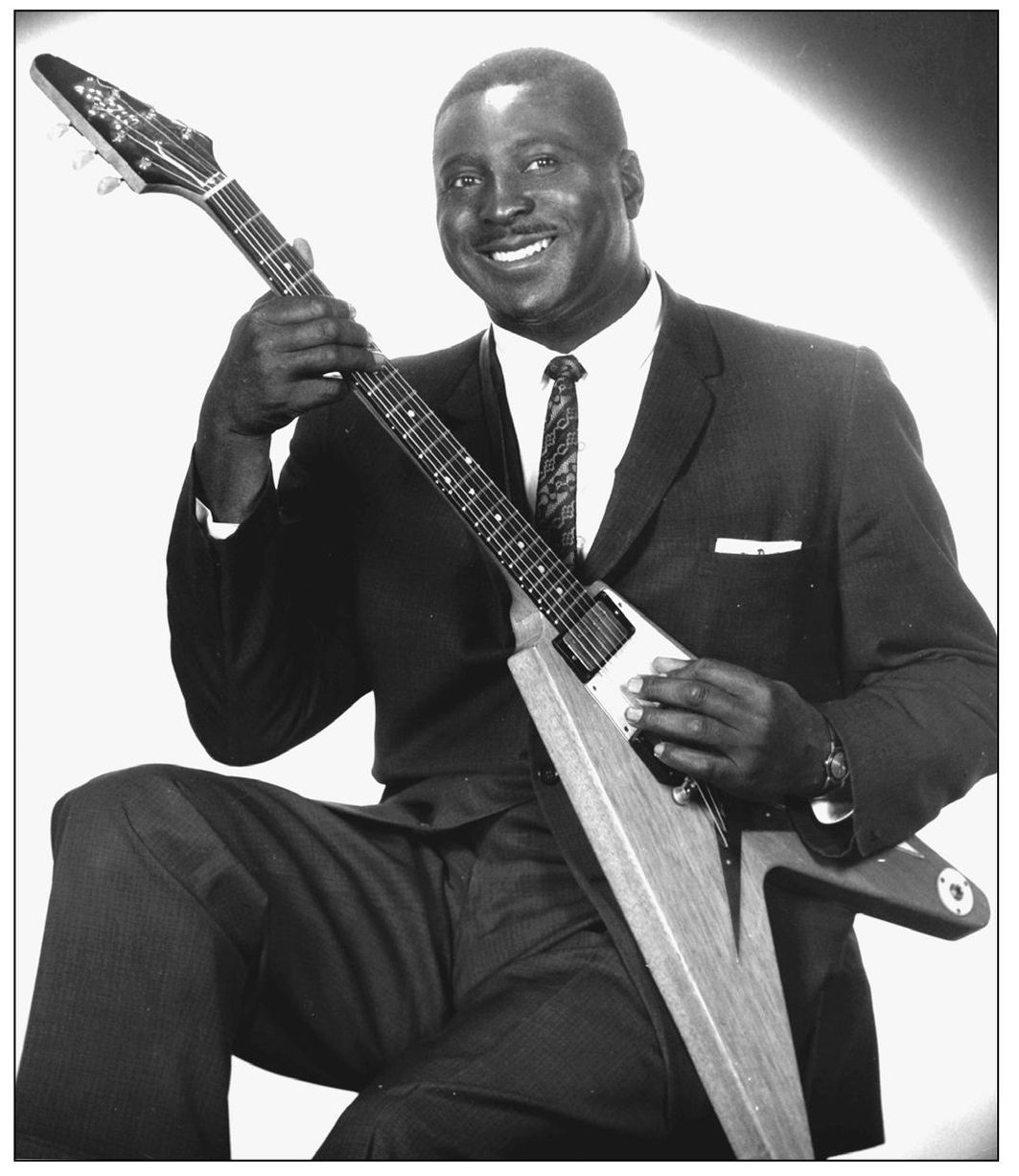

In 1961, Mississippi blues singer Albert King started a string of R&B hits with “Don’t Throw Your Love on Me So Strong.” It was his biggest record; King acquired it from the Bobbin label. Previously he had been with the Harmony Kings gospel group and Parrot Records. Later he signed with Stax Records. Here he poses with his Flying V. (Author’s collection.)

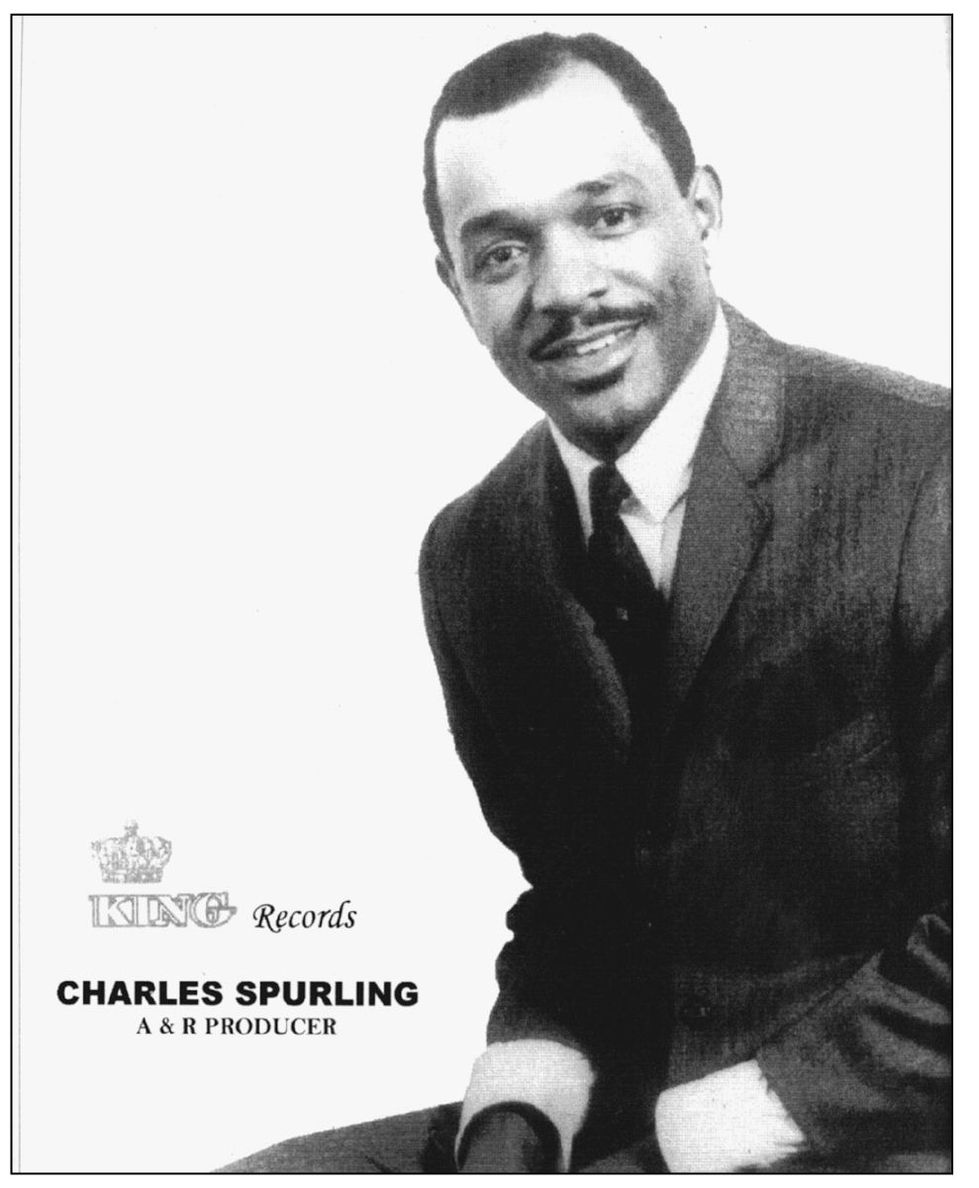

Charles Spurling of Lincoln Heights entered King Records as an A and R man in the mid-1960s. Soon he was recording his own singles and working with the Sisters of Righteous, a female vocal group from Cincinnati that sang on sessions and at times backed James Brown. One of Spurling’s singles was “Popcorn Charlie.” (Courtesy of Charles Spurling.)

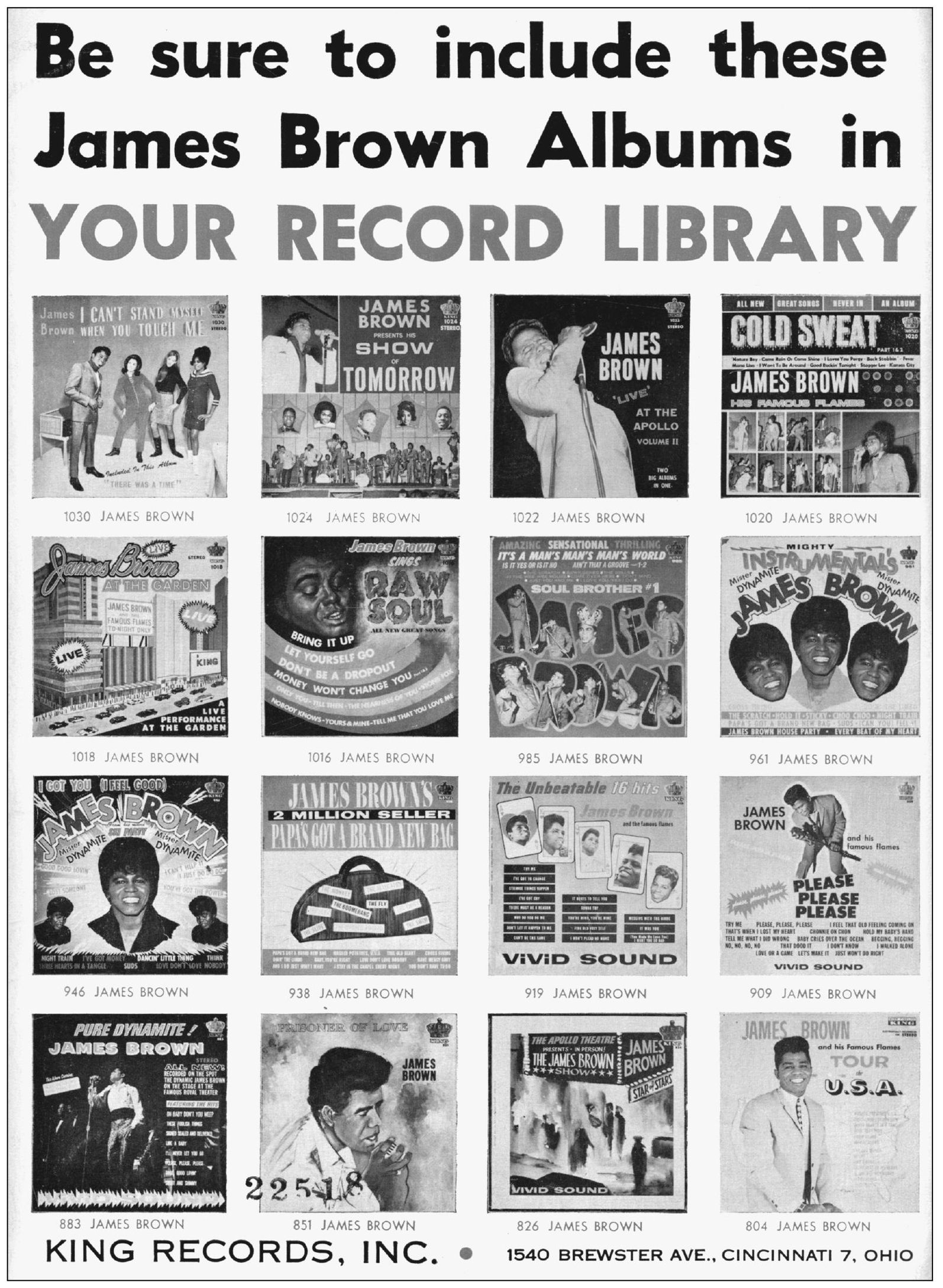

James Brown could not complain about a lack of publicity. King Records hawked and advertised him at every opportunity. This collage of colorful album covers—garish even in black and white reproduction—was printed on the back of a song folio. King Records designed most of its own album covers. Some of Brown’s covers featured women wearing mini-skirts, go-go boots, and, yes, hot pants. (Author’s collection.)

Brown’s war for independence was not won with one hit record. He had to prove himself with every unusual track that he recorded. Naturally he clashed with Syd Nathan. It was not that Nathan had “tin ears,” as some people assume. After all, the man founded the financially successful Lois Music, discovered talented songwriters, and personally oversaw hundreds of early country and blues sessions that yielded dozens of hits. After remastering many of King’s early recordings in Nashville, engineer Mike Stone said, “On the tapes I could hear Mr. Nathan right there, behind the board, giving orders. He produced those early records.” But Nathan’s standard operating method—a song needs a catchy melody, a bridge, and an identifiable lyric line—was not necessarily Brown’s. He dealt in riffs and beats. The two worlds clashed. (Author’s collection.)

The summer of 1968 was “Hot! Hot! Hot!” In this advertisement, James Brown returns with “I Guess I’ll Have to Cry, Cry, Cry”—his last period single with the Famous Flames. The record peaked at No. 15 on Billboard’s R&B charts. Ballard’s record was not so fortunate. But he did return to the charts with “How You Gonna Get Respect (When You Haven’t Cut Your Process Yet),” a single obviously aimed at R&B radio. It also peaked at No. 15, ironically, with the music of soulful white session players, the Dapps. Brown discovered the group in Cincinnati’s Inner Circle nightclub and used the band on his and other performers’ recordings. At various times the band included guitarist Troy Seals, who became a major Nashville songwriter; Tim Hedding, organ; Eddie Setser, guitar; Tim Drummond, bass; Les Asch, saxophone; and Beau Dollar, drums. (Author’s collection.)

Hank Ballard’s 1961 hit “The Switch-A-Roo” peaked at No. 26 on Billboard’s pop music chart. Its flip side, “The Float,” also received enough airplay to break into the chart. (Author’s collection.)

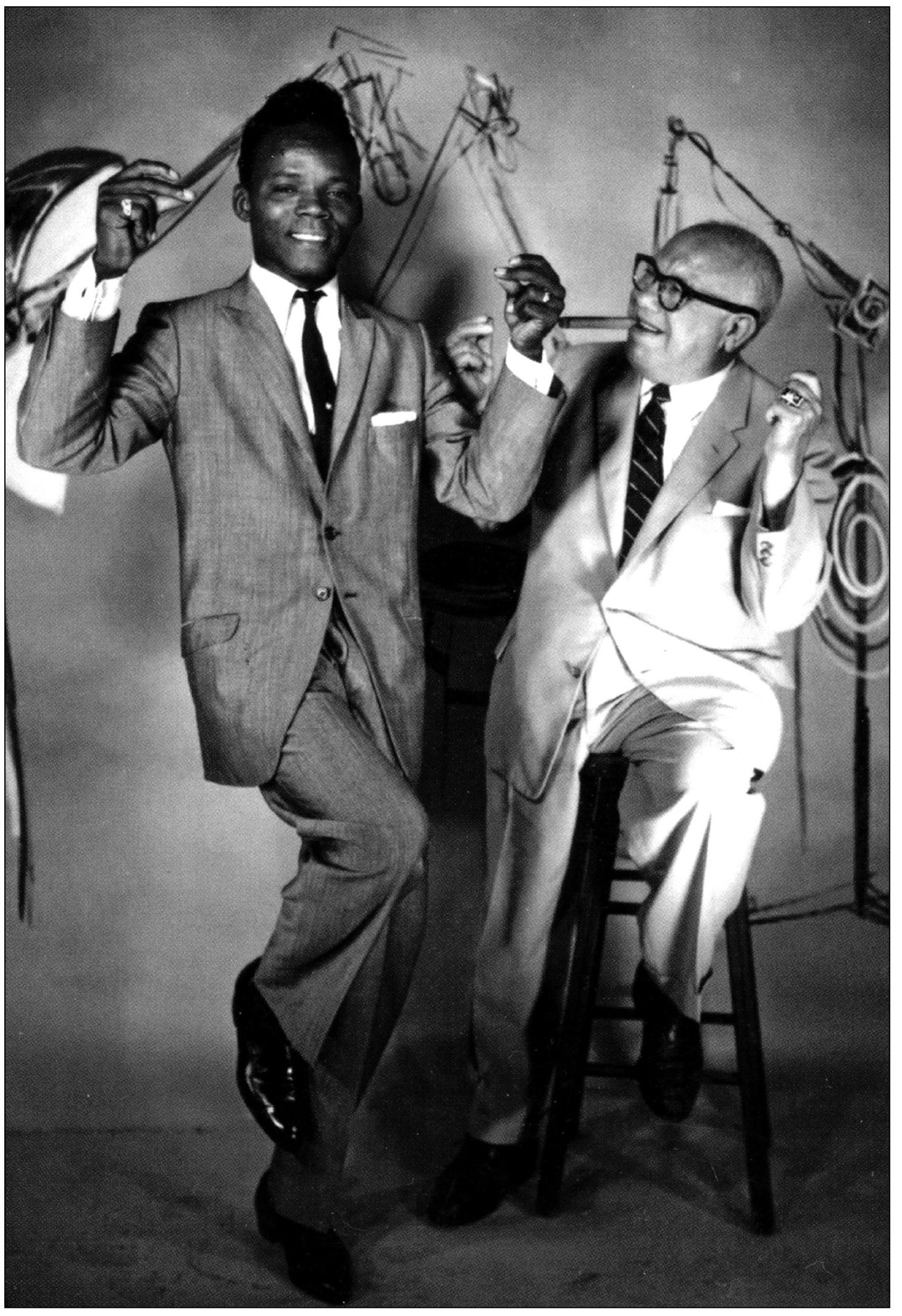

Although in later years Hank Ballard complained about Syd Nathan’s management style, they both agreed to pose for this publicity shot in the early 1960s. By then, “The Twist” had brought Ballard much attention. Like Brown, Ballard was a top King Records act that remained under contract with the company for most of his long recording career, starting in 1953 and continuing until the label was finally sold again in 1971. And like Brown, his contract then went to Polydor Records. (Courtesy of Steven D. Halper.)

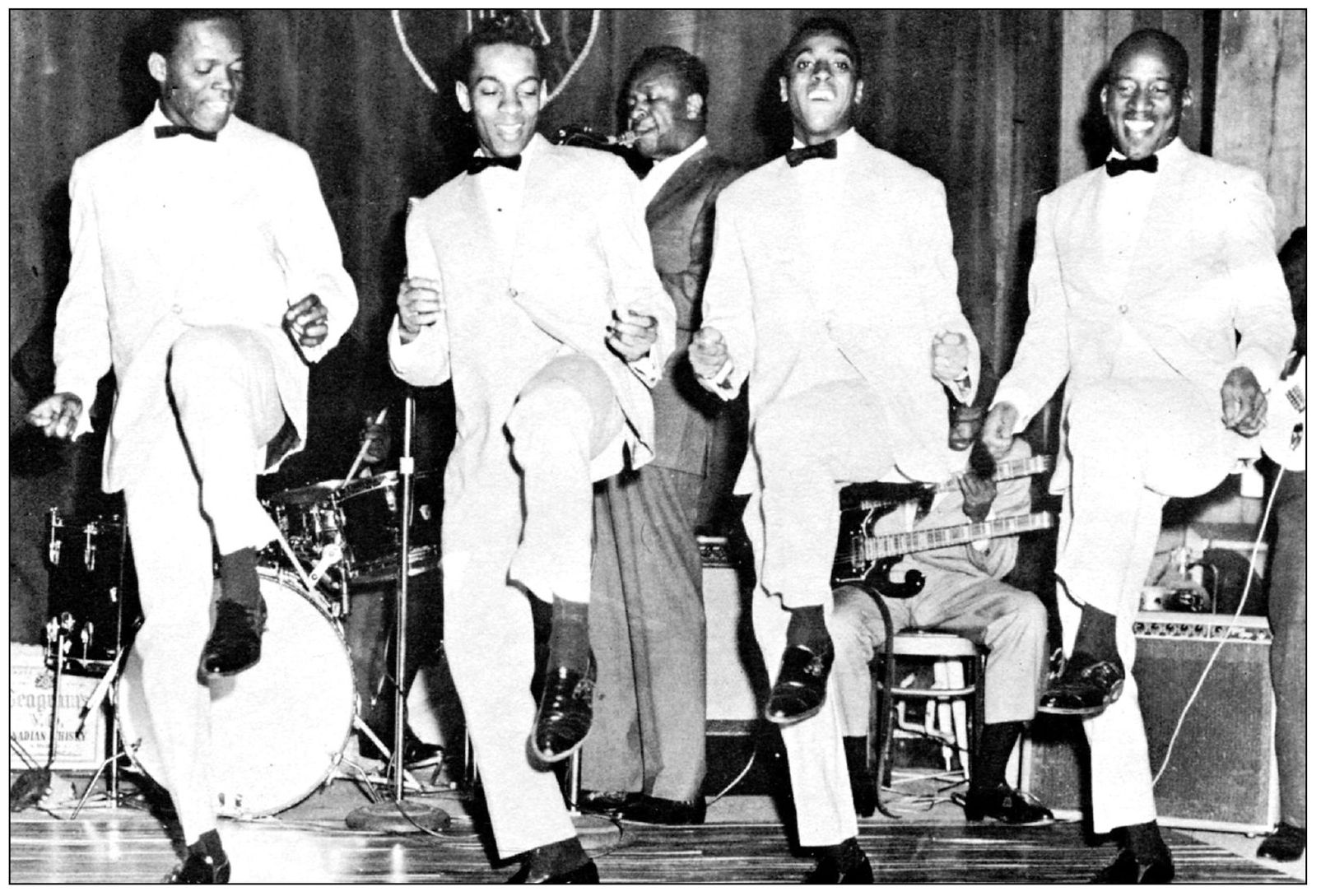

The Midnighters kick up their heels during a performance. They recorded a master tape of “The Twist” in King’s Cincinnati studio on November 11, 1958. Chubby Checker’s version, recorded in 1960 in Cameo Records’ small studio in Philadelphia, essentially copied the King arrangement, with a slightly lighter feel. Checker also tinkered with the dance itself, making it look like he was putting out cigarettes with his feet. (Author’s collection.)

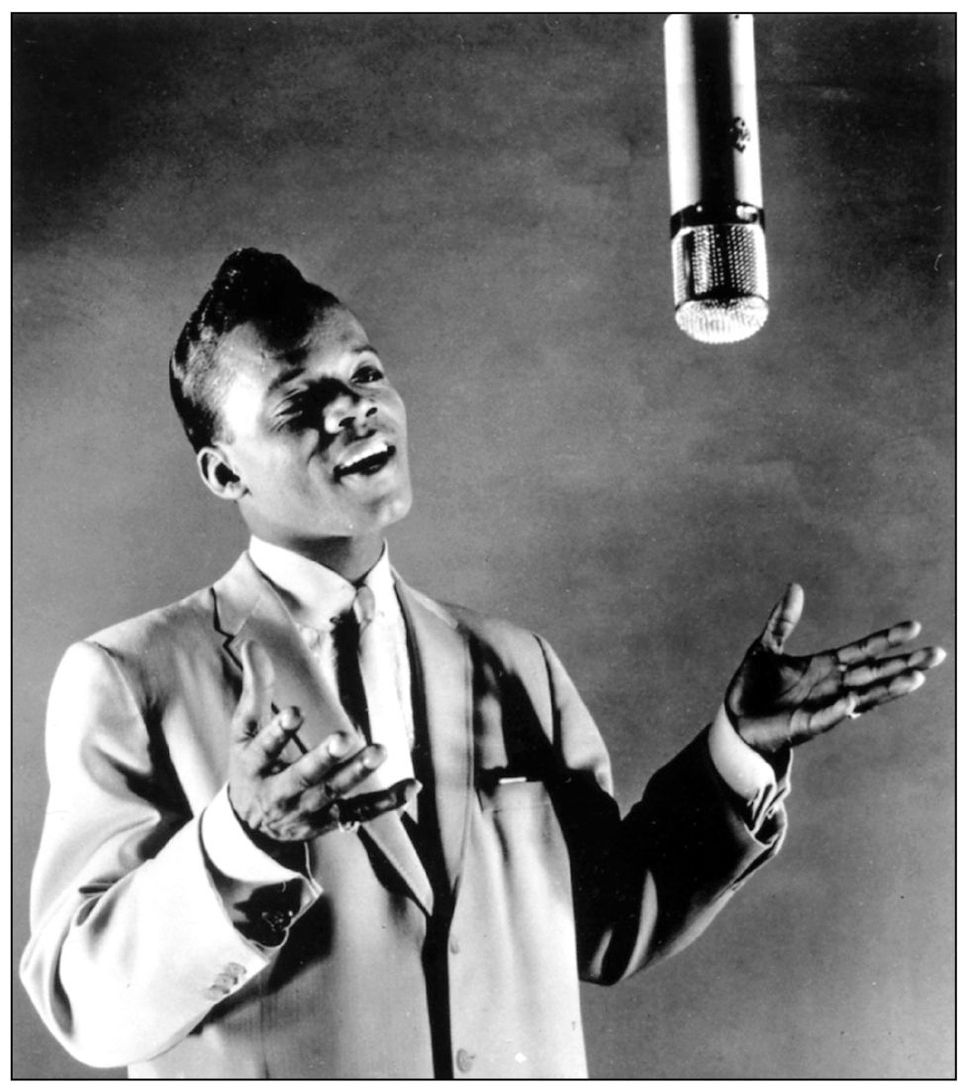

In this c. 1960 photograph, Hank Ballard poses in front of a vocal microphone. In the late 1960s, he hired 16-year-old Bootsy Collins of Cincinnati and his band to back him on the road. Although Collins felt honored to perform on stage with the star, he also felt embarrassed when Ballard sometimes disappeared after shows—without paying the band. (Author’s collection.)

Lucius “Lucky” Milllinder’s biggest contribution to King was his band. In the 1940s, the Chicago-based entertainer permitted defections from trumpeter Henry Glover, who became a King Records A and R executive and songwriter—the most important behind-the-scenes leader, other than Nathan. Millinder himself had a big King hit in 1951—“I’m Waiting Just for You,” with vocals by Annisteen Allen and John Carol. (Author’s collection.)

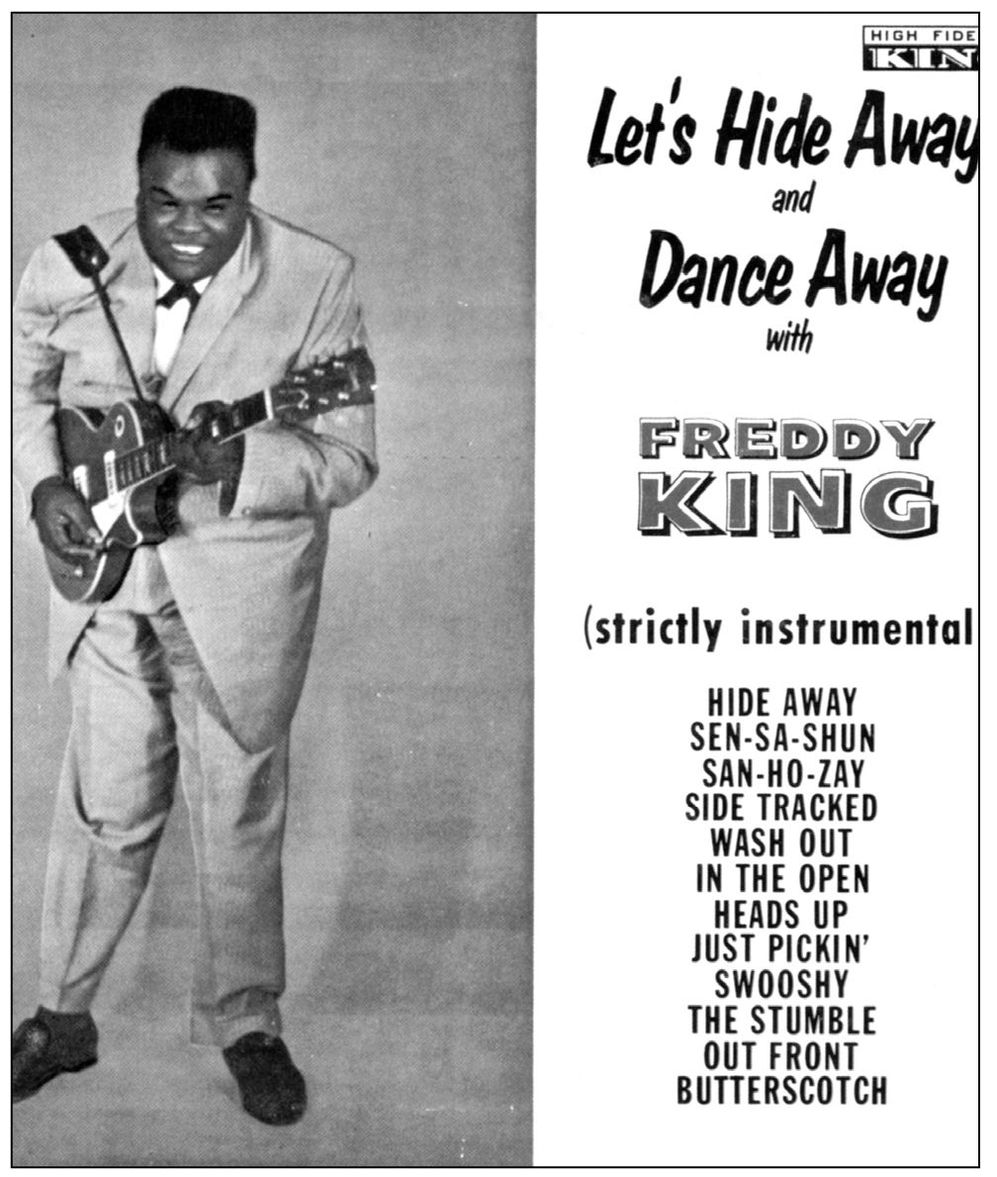

Blues vocalist Freddy King, born Freddy Christian in Gilmer, Texas, holds his guitar. He recorded for Chess and other labels without much luck and sang in clubs and played on sessions in Chicago. In 1961, he came to King Records’ studio to cut “Hide Away,” a title inspired by a Chicago lounge. He followed with “Lonesome Whistle Blues,” “San-Ho-Zay,” and other Federal Records hits—six of them in only one year. Cincinnati musicians such as guitarist Lonnie Mack and organist Bob Armstrong acknowledge Freddy King’s influence on local players during his short time in the city. The company also released an EP called Hide Away, which is highly collectible. (Author’s collection.)

King Records’ contributions to doo-wop are overshadowed by its country and blues efforts. The Swallows, the Platters, the Five Keys—actually, there were enough groups to start a whole company. In 1951, the Swallows hit with “Will You Be Mine.” The Five Keys, from Newport News, Virginia, turned out hits with Capitol Records before joining King. Still, the group’s less known King recordings are popular among collectors. (Author’s collection.)

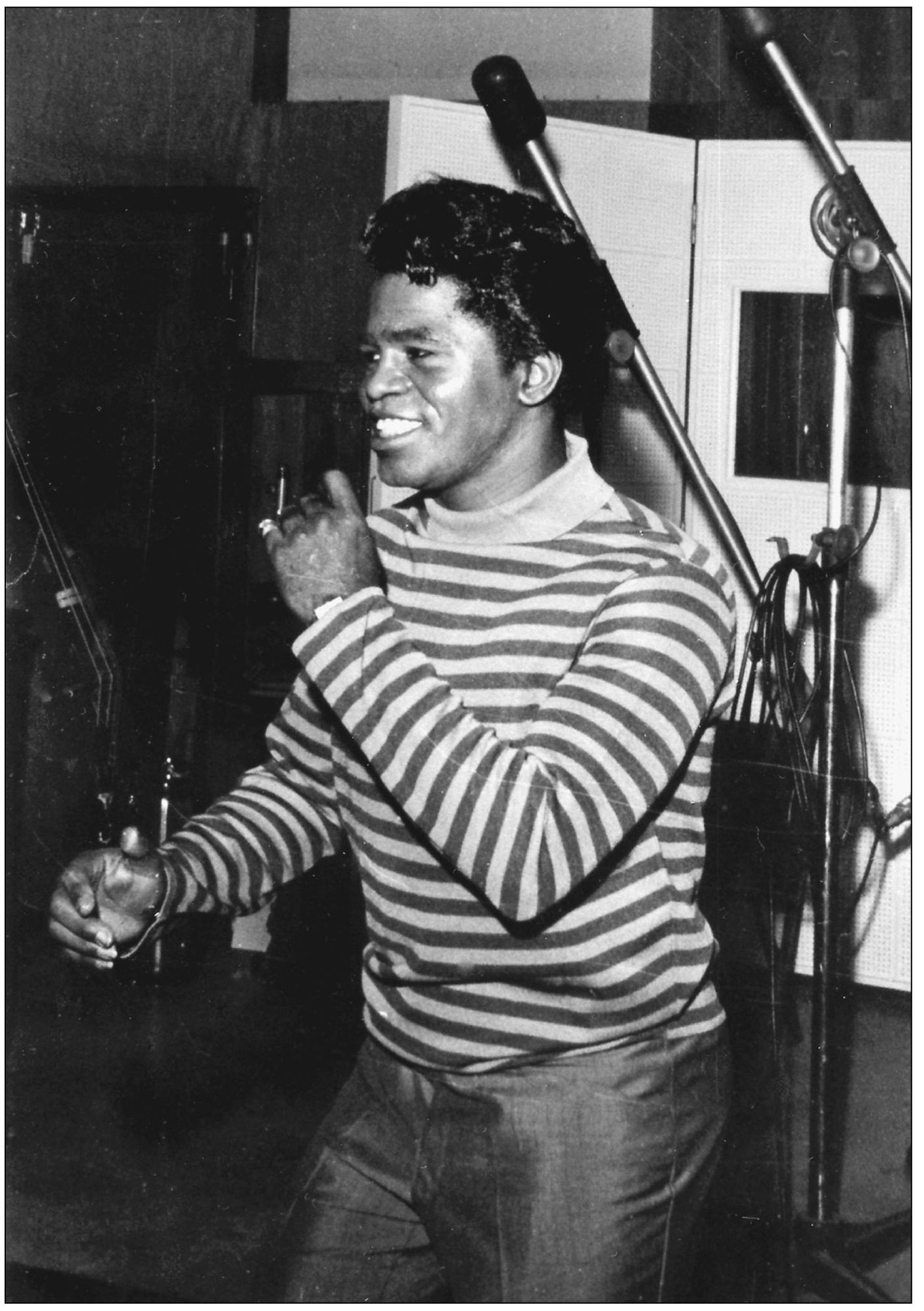

James Brown rocks onstage around 1968. When he was eight years old, he danced for National Guard soldiers, who threw him spare change. Later his fellow students paid to watch him dance. (Author’s collection.)

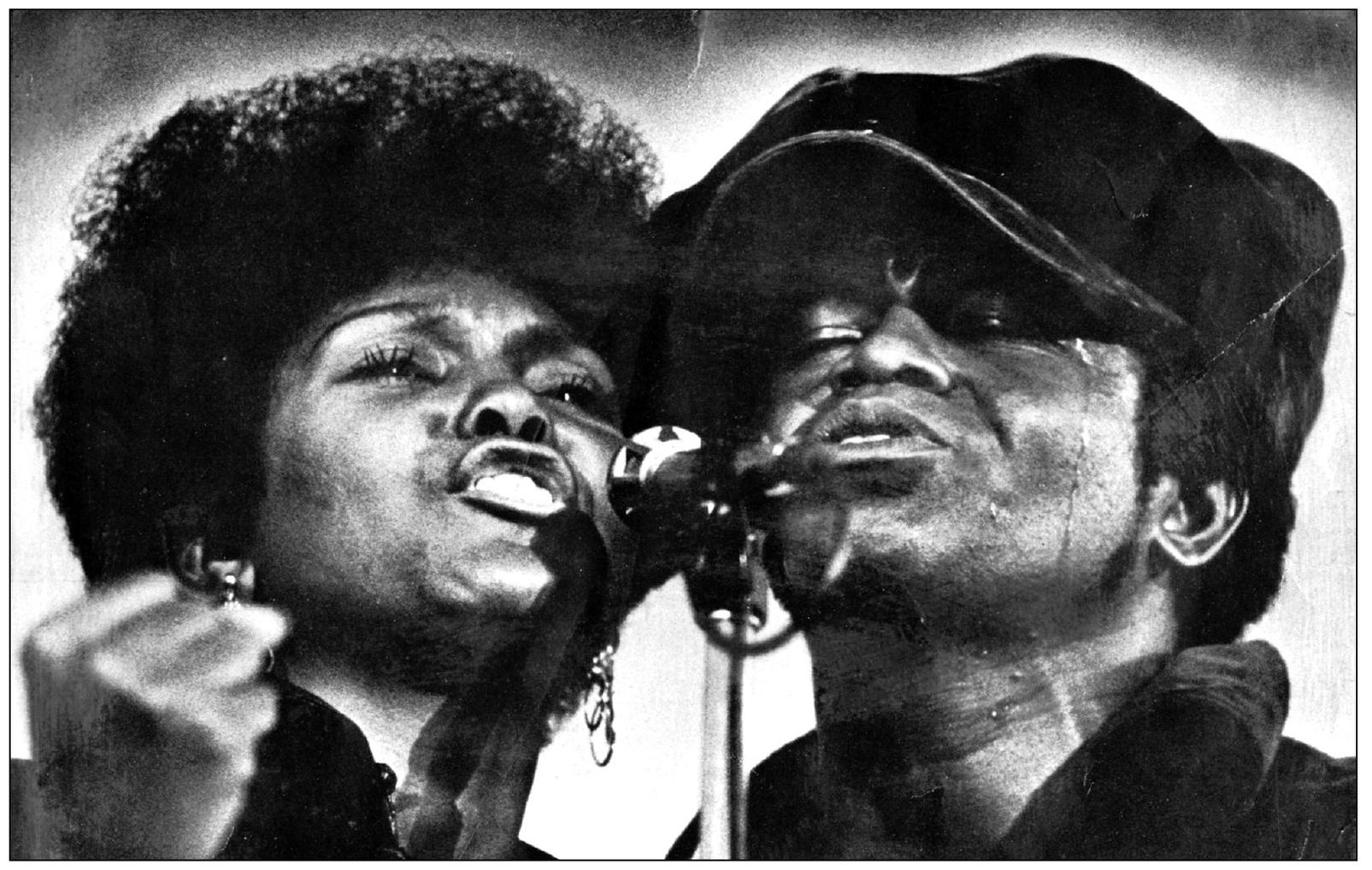

By the late 1960s, James Brown was operating his own labels, including People Records, out of the King Records plant in Evanston, and recording his own artists as an independent producer. One of them was Vickie Anderson, with whom he did some recording. King Records A and R man Charles Spurling remembers her as being exceptionally talented. (Courtesy of Charles Spurling.)

James Brown Productions became an independent group within the King Records organization. This is one reason why Brown signed a new contract in 1966. Where else could he have received such a sweet deal? Brown ran his operation his way. He had his own A and R, promotional, and production people. He even put his picture on other acts’ records. (Author’s collection.)

In this c. 1967 photograph, Brown looks bewildered as he stands with a crown on head. The other people in the crowd are unidentified. The crown is fitting, however, for by that time his sales power was the force driving King Records. (Courtesy of Steven D. Halper.)

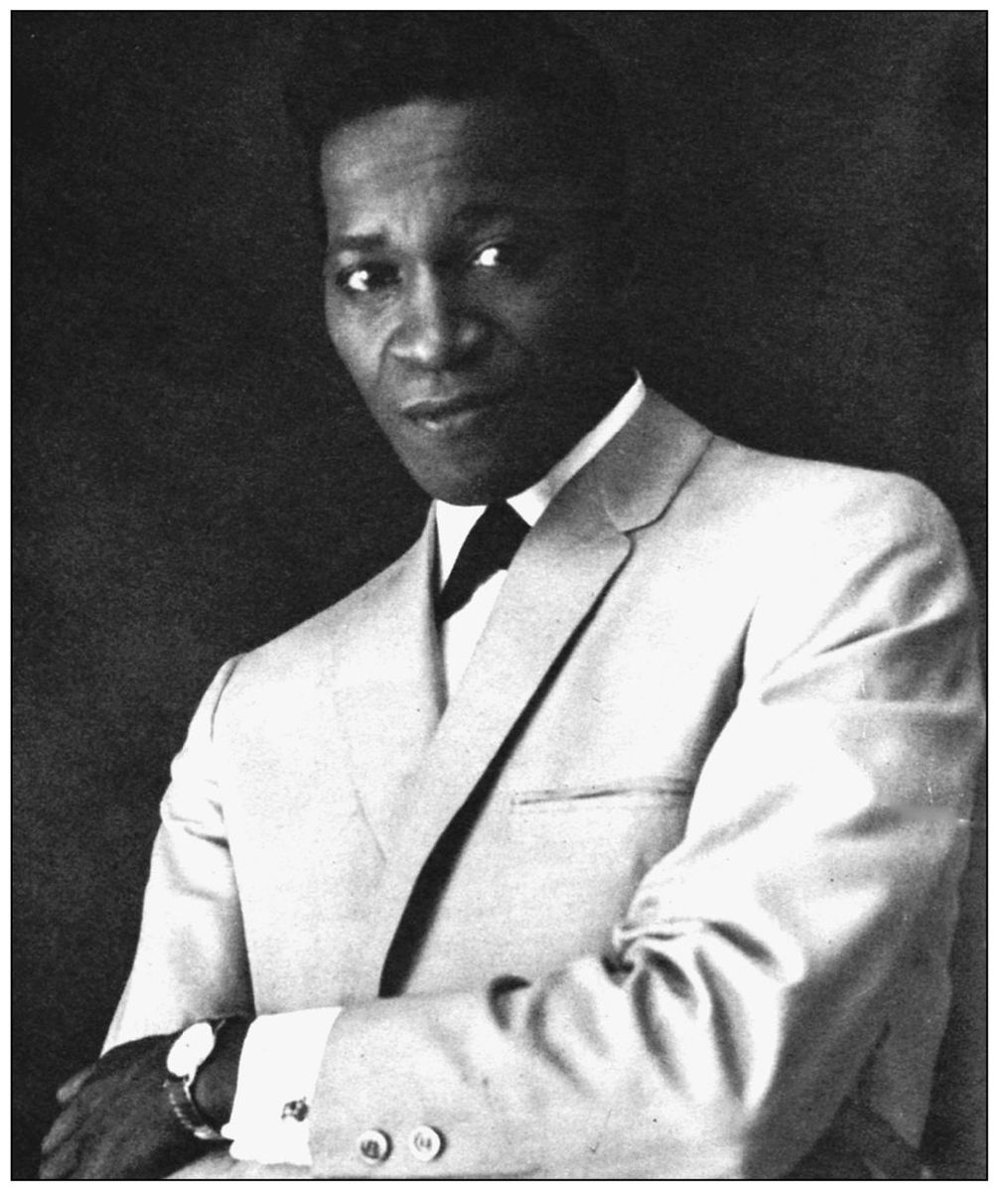

Detroit vocalist William Edgar “Little Willie” John—not to be confused with Federal Records’ Little Willie Littlefield—became a solo R&B star for King Records in 1955 when he hit with “All Around the World.” Other big hits included “Fever” and “Talk to Me, Talk to Me.” While serving a prison sentence for manslaughter in 1966, he died of a heart attack. (Author’s collection.)

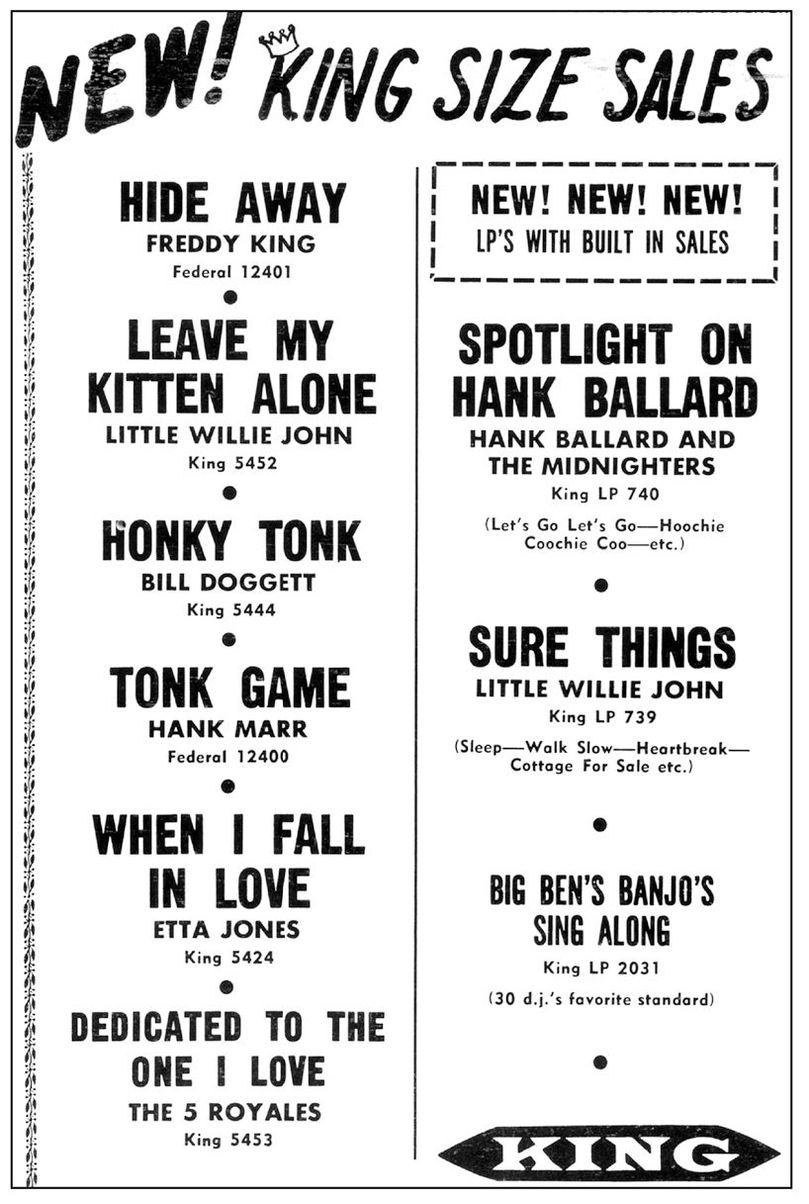

This advertisement announces King Records’ new singles and albums in early 1961. Organist Bill Doggett’s often-recorded “Honky Tonk” is back, along with “Tonk Game” by his would-be successor, Hank Marr. Of course, fan favorite Little Willie John returns. (Author’s collection.)

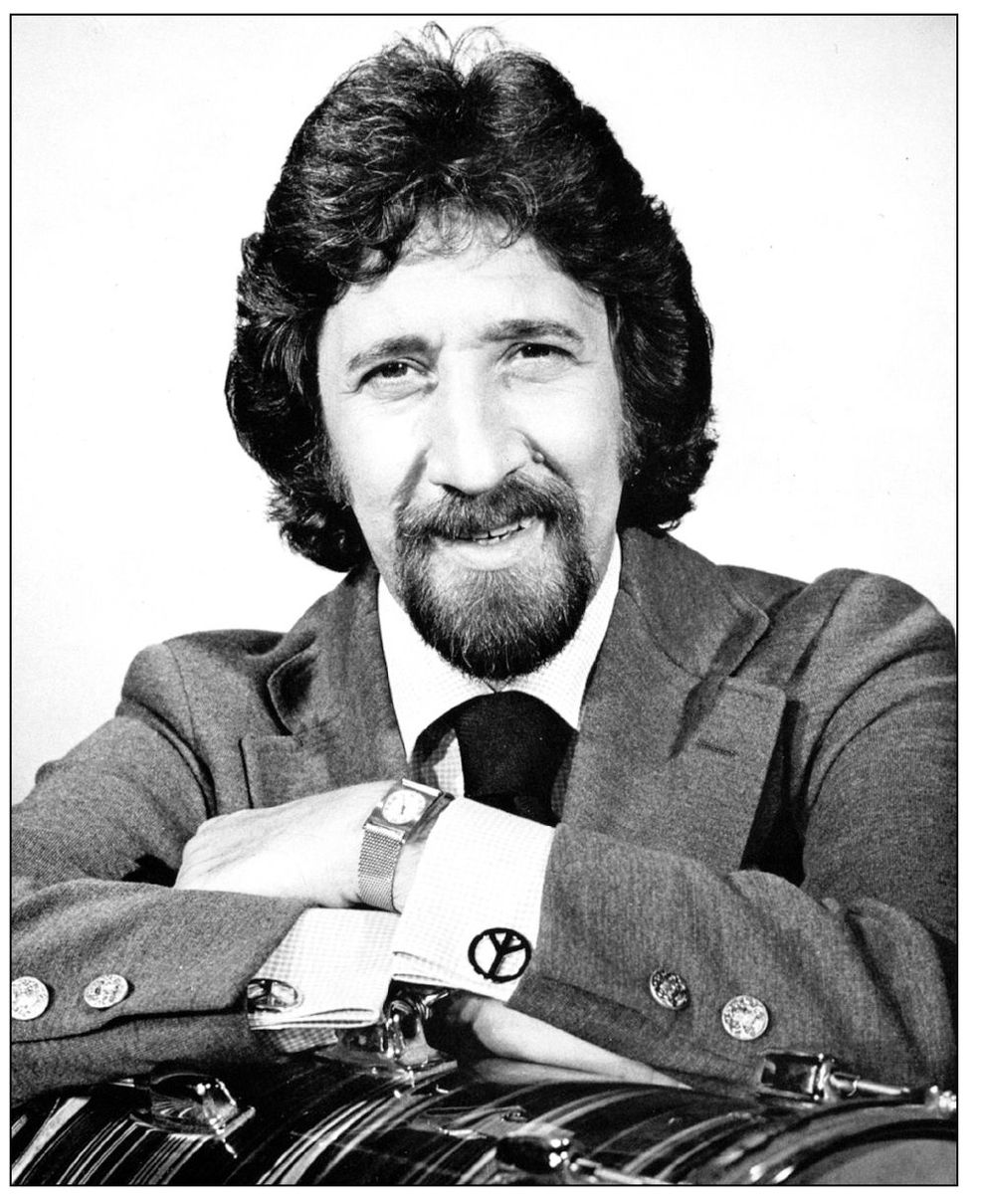

Talented Cincinnati jazz drummer Dee Felice—born Emidio DeFelice—played on sessions at King Records and recorded for the label’s subsidiaries, often under the guidance of James Brown. One Felice album was called In Heat. In this c. 1968 photograph, Felice sports peace symbol cuff links—a symbol of the era. (Courtesy of Shelly Nelson.)