Six

DADDY-O DAYS

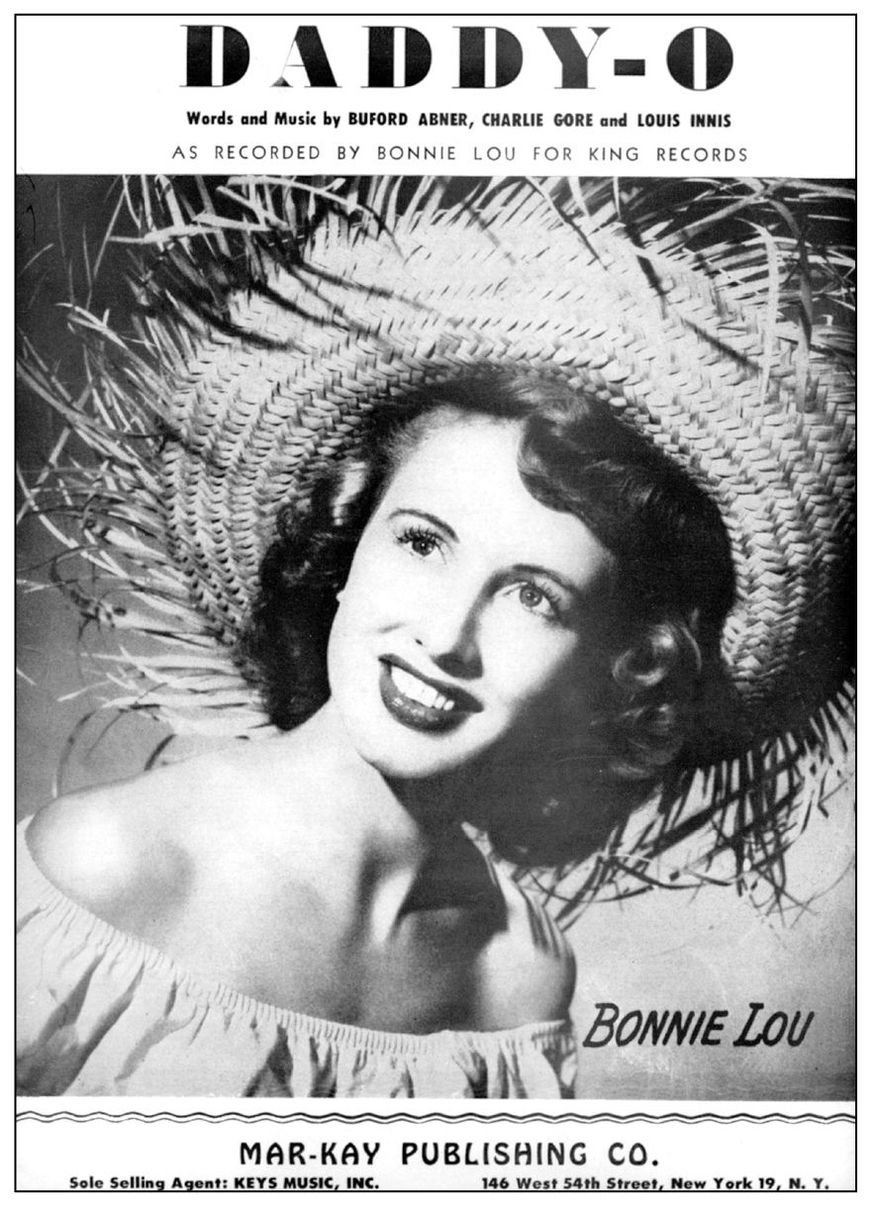

By 1955, Bonnie Lou needed another hit. So King Records experimented. Louis Innis, King Records’ A and R man from Indiana, wrote a song called “Daddy-O” with singer Charlie Gore and musician Buford Abner. It was cutting-edge rockabilly—teenage fare. And it hit big. (Author’s collection.)

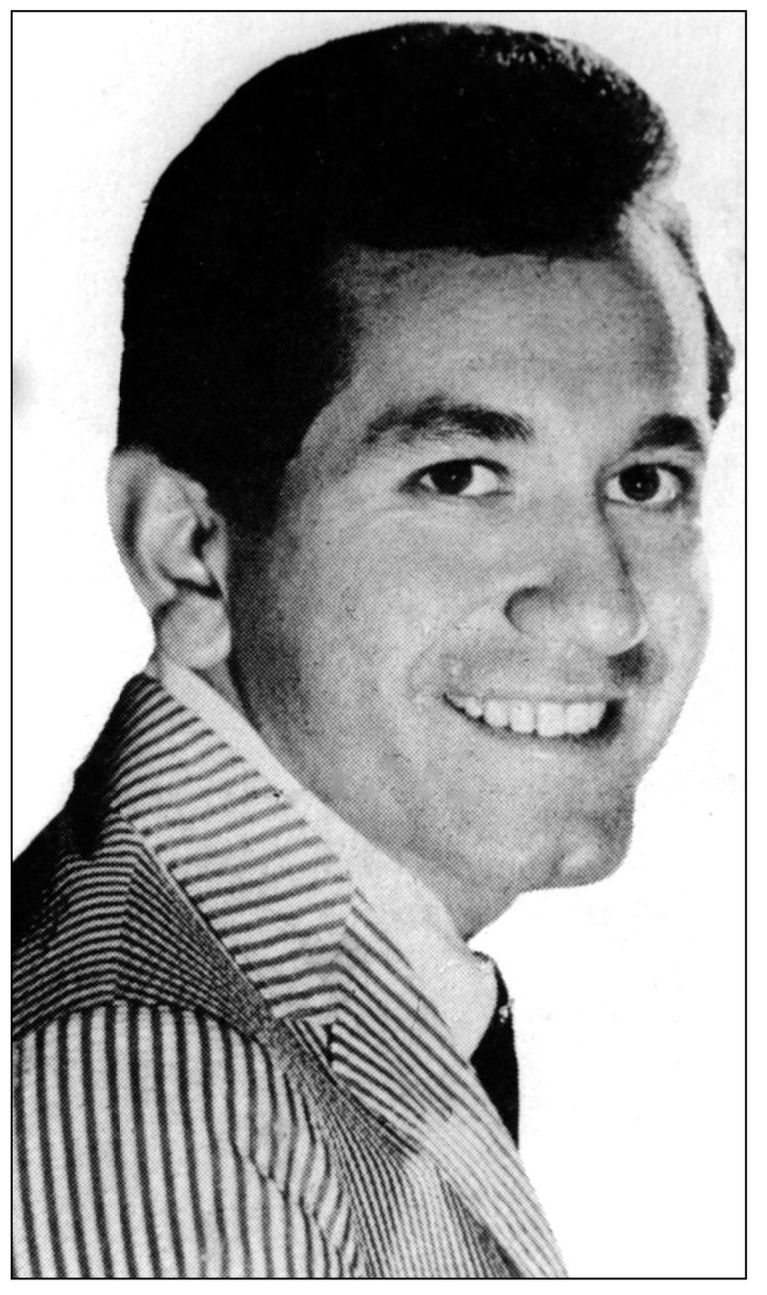

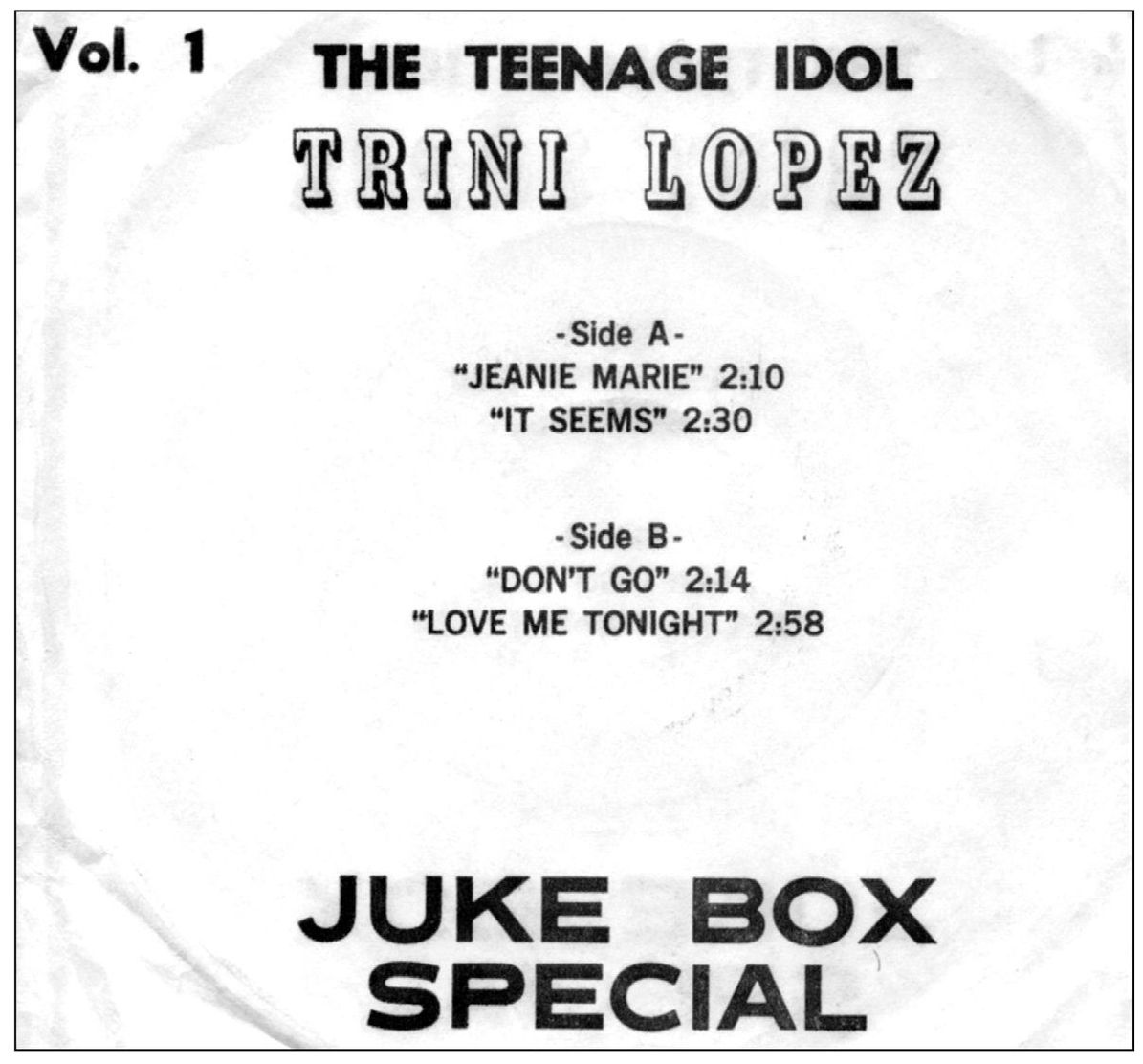

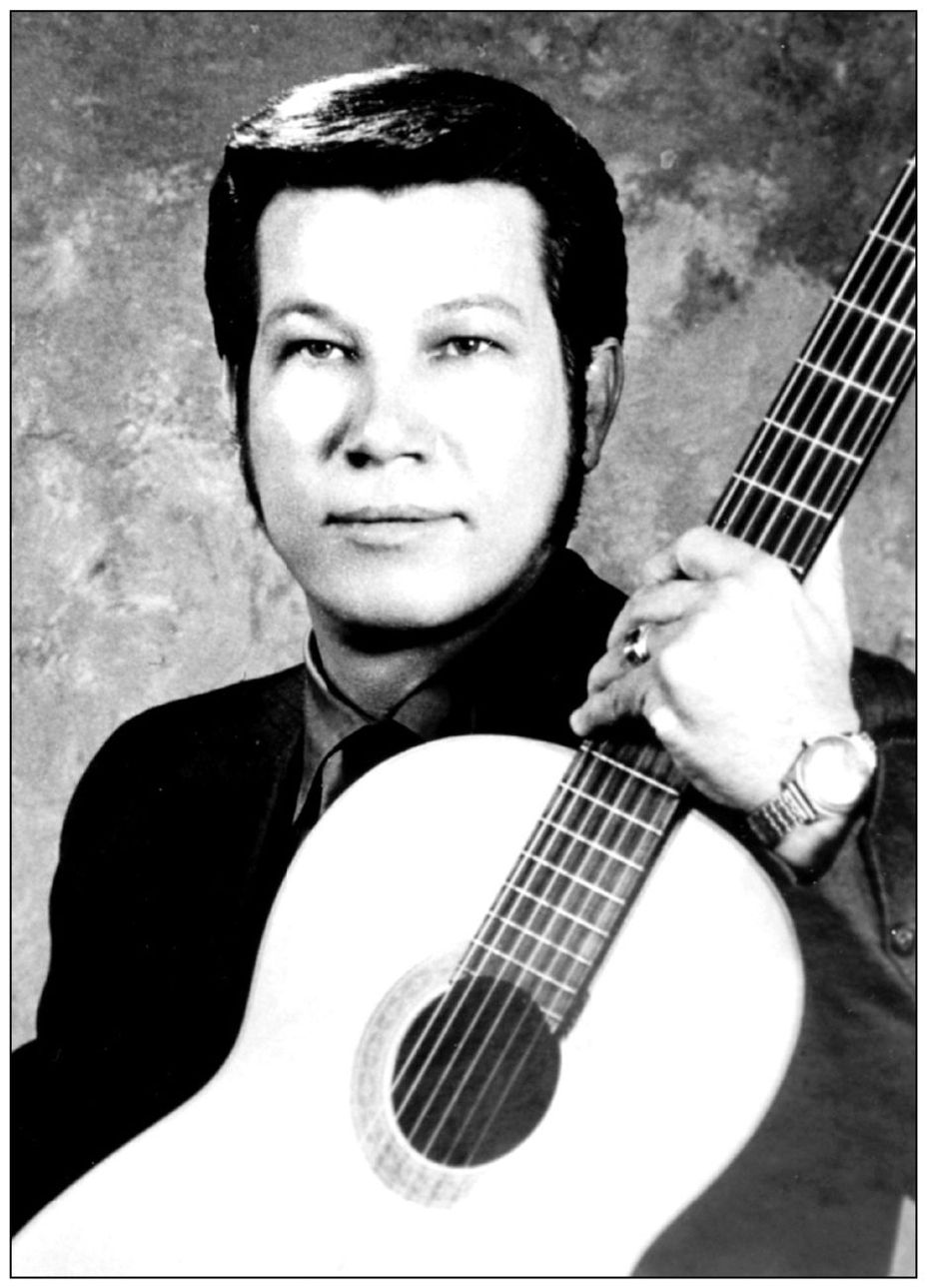

King Records signed Texan Trini Lopez in 1957, hoping to make him the Hispanic Elvis—or at least another Carl Perkins. In Dallas in 1958, Lopez recorded a couple of singles, but they did not sell nationally. This was still a year before another young Hispanic, Ritchie Valens, arrived on the national charts with Del-Fi Records of California. (Author’s collection.)

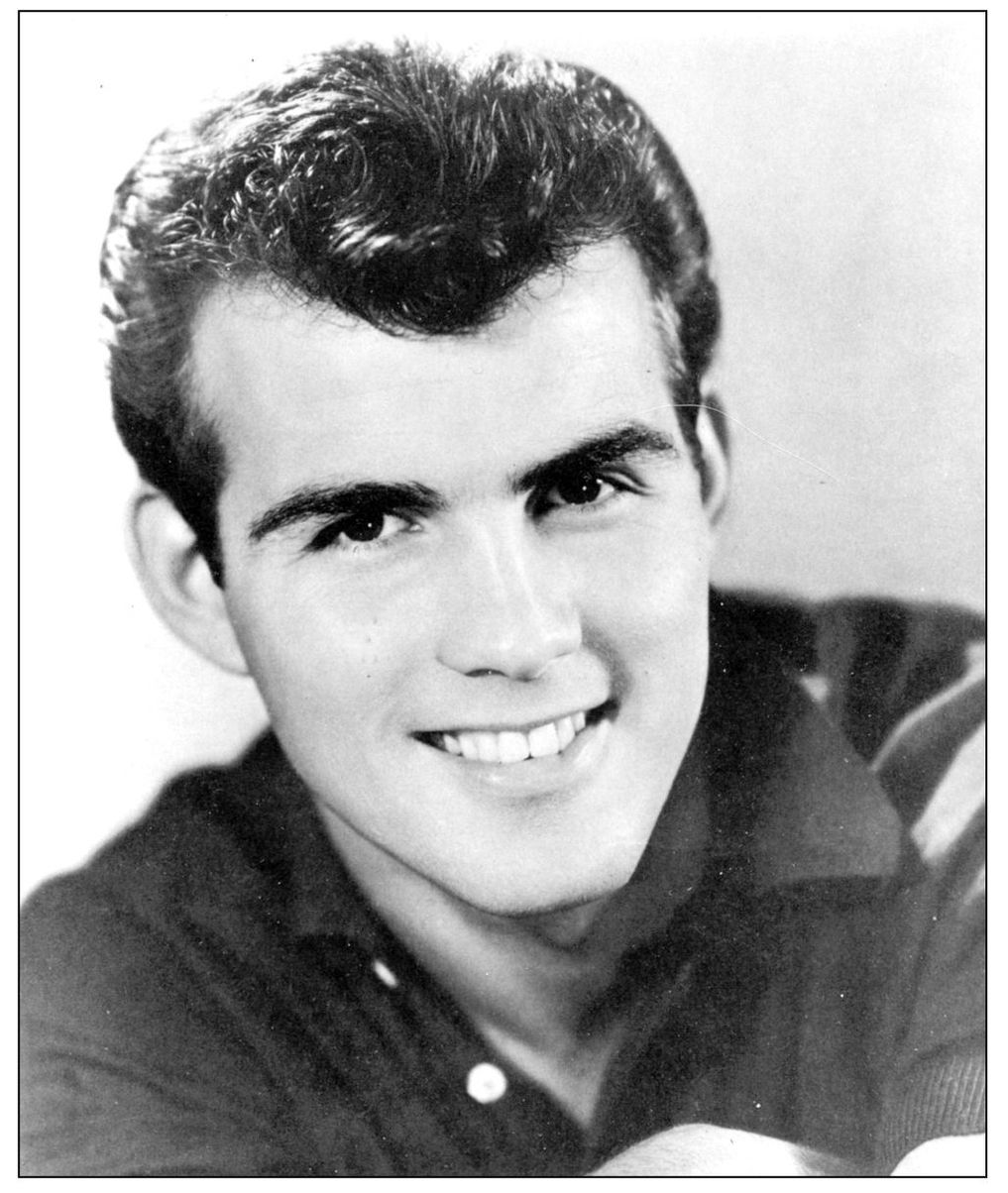

In early 1959, Lopez came to King’s Cincinnati studio to record “Rock On” and three other songs. Although the company tried hard to promote them, the timing was not yet right. Lopez would have to modify his musical style and wait until 1963 to start a five-year run on the singles charts that began with “If I Had a Hammer” on Reprise Records. (Author’s collection.)

Billy “Crash” Craddock, a North Carolina rockabilly and country singer, came to King Records in 1964. In the Cincinnati studio he recorded “Teardrops on Your Letter” and other singles but with little success. In 1969, he found his first elusive hit with “Knock Three Times” on Nashville’s Cartwheel Records. He earned his nickname by crashing through opposing football teams’ lines in high school. (Author’s collection.)

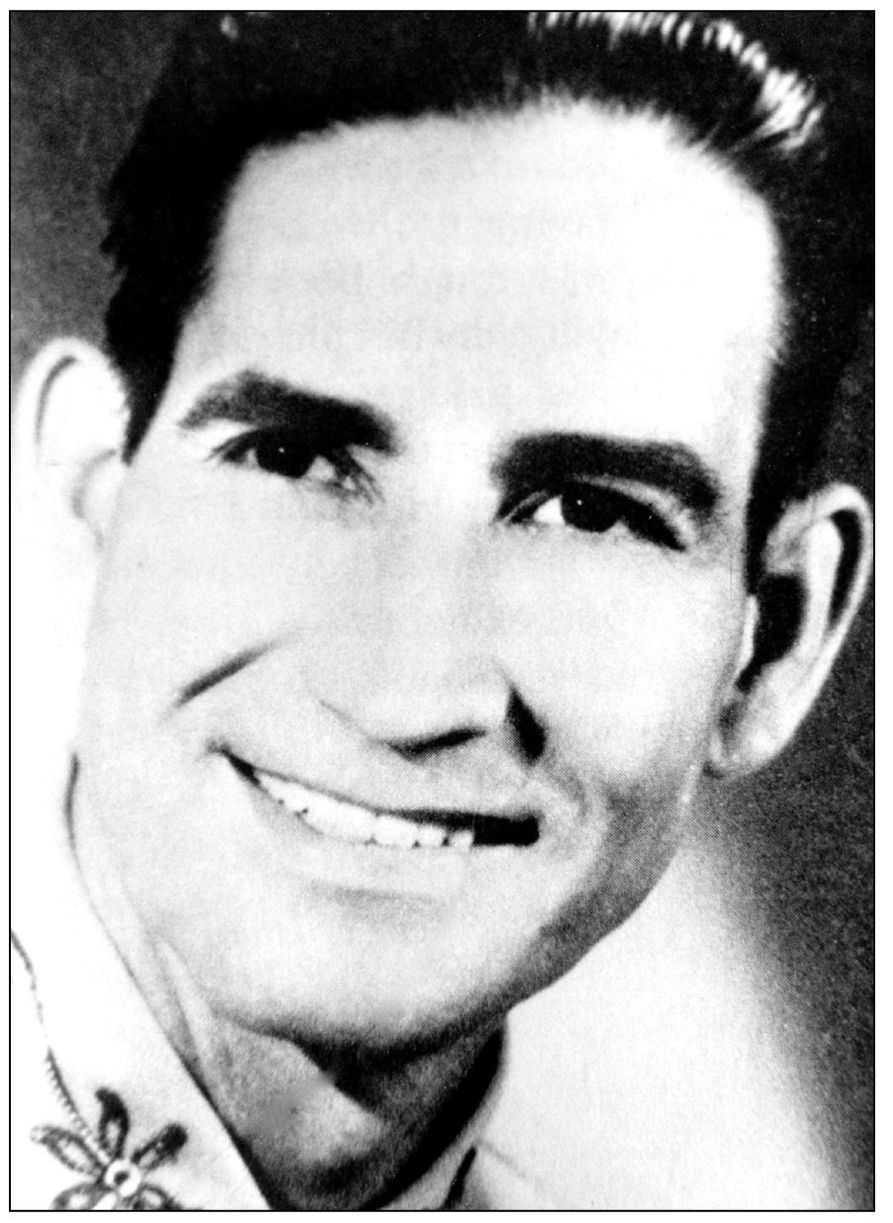

Lattie Moore of Indianapolis was a country singer when he recorded for King Records, but in the late 1950s he was recording some rockabilly-tinged songs for independent labels. In 1963, he came to Cincinnati to record “Honky Tonk Heaven” backed with “Just About Then.” He kept this photograph in a drawer for years without looking at it. (Author’s collection.)

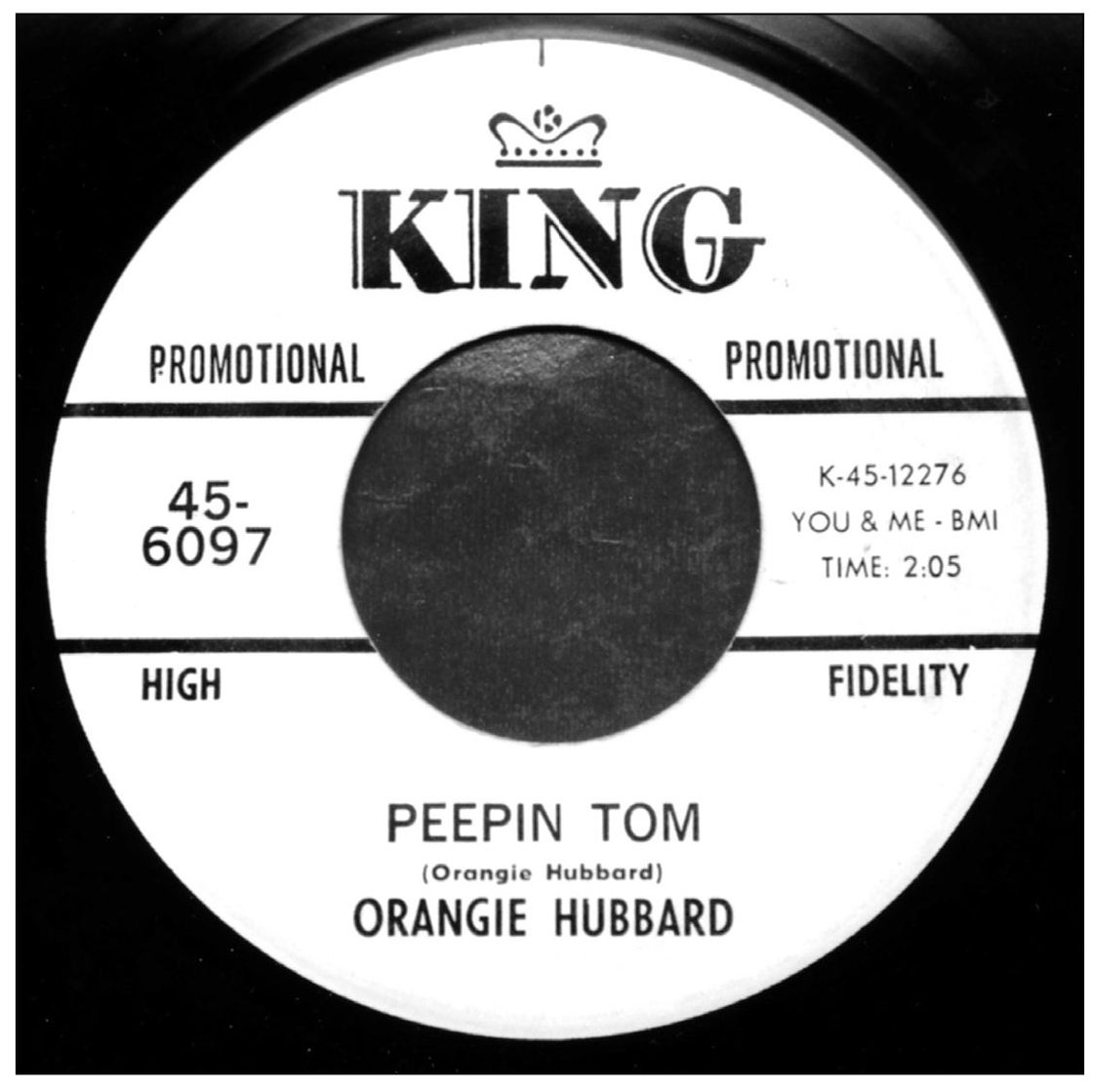

Kentucky native Ray “Orangie” Hubbard worked in a Cincinnati automobile factory by day and played music by night. In the 1950s, the singer-songwriter recorded hot rockabilly for El Rader’s Lucky Records and other small Cincinnati labels, and by the mid-1960s he was recording for King Records. (Courtesy of Ray Hubbard.)

The company issued singles such as “Peepin’ Tom,” and Hubbard was hopeful. “But then Syd Nathan died,” he said. “That left me in limbo.” He continued to perform in nightclubs around town and gained a reputation as a country and rockabilly original. “When I joined King,” he remembered, “Mr. Nathan said, ‘Look, boy, you ain’t the best damn singer I ever heard, but you’re not the worst. Here’s a contract. Make up your mind.’ ” (Courtesy of Ray Hubbard.)

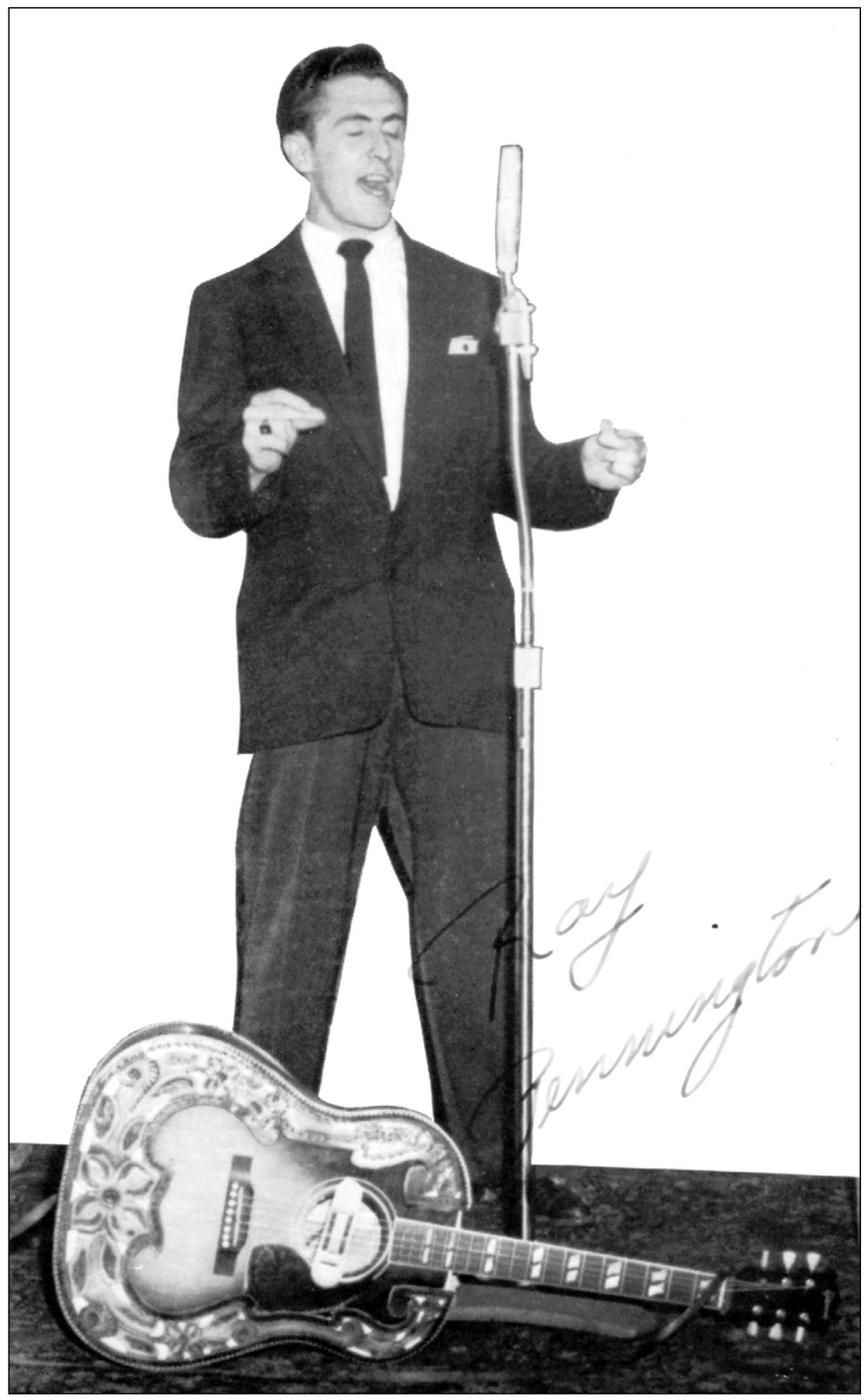

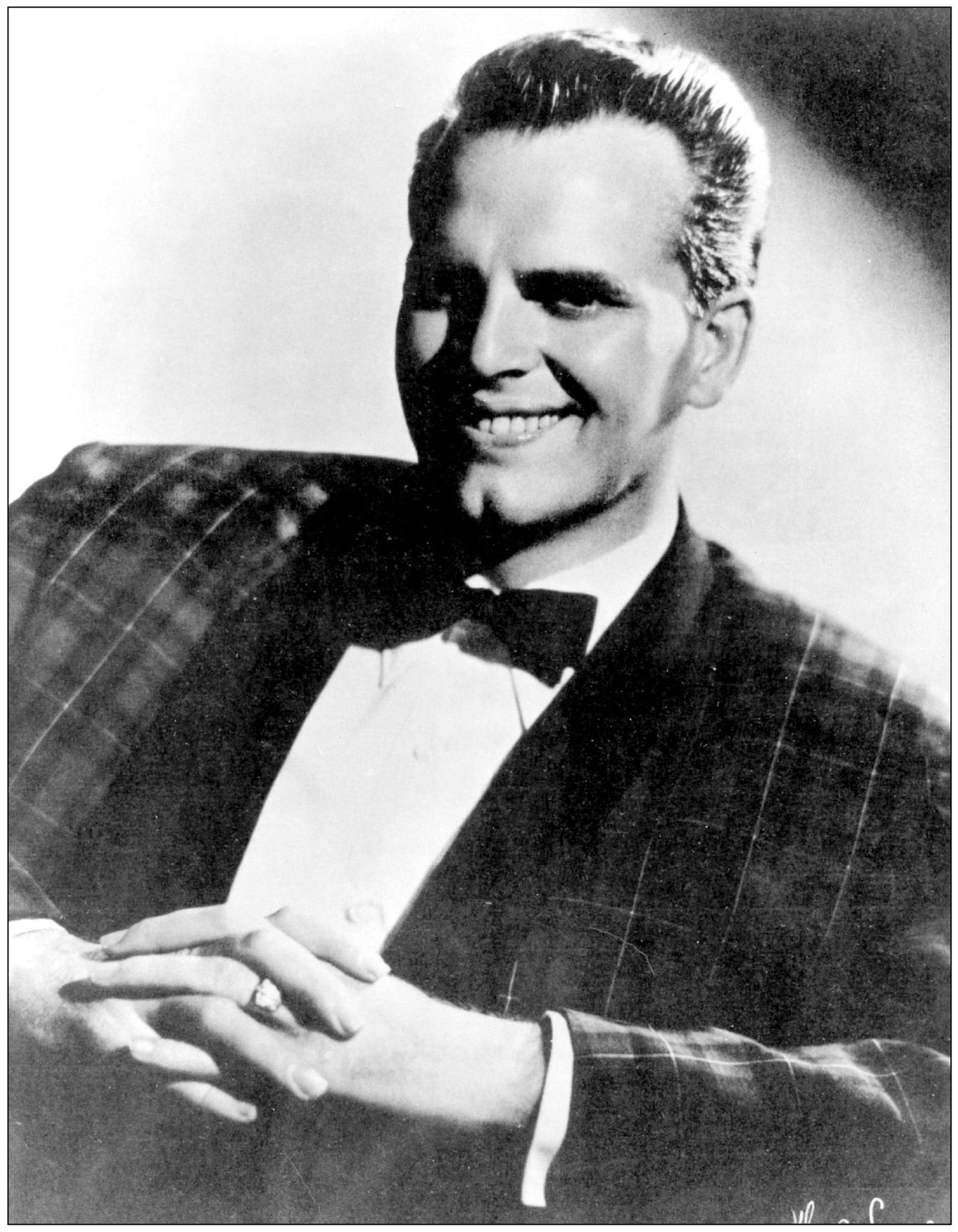

Ray Pennington performed in Cincinnati-area clubs with his large country band. By 1961, he started working as a clerk at King Records, and soon he was promoted to A and R man. His own releases were under Ray Pennington or the pseudonym Ray Starr. He said he tried to record country as Ray Pennington and rock ’n’ roll as Ray Starr, but the styles were interchangeable. His band backed other King Records acts on sessions, including Swanee Caldwell. Pennington also produced the Stanley Brothers and Hawkshaw Hawkins’s 1963 comeback hit “Lonesome 7-7203.” He said, “We’ll never see another record company like King again. Syd Nathan was a genius. If he couldn’t find the singer he wanted, he’d buy somebody’s [old] masters. That’s how he got Patsy Cline, I believe.” (Author’s collection.)

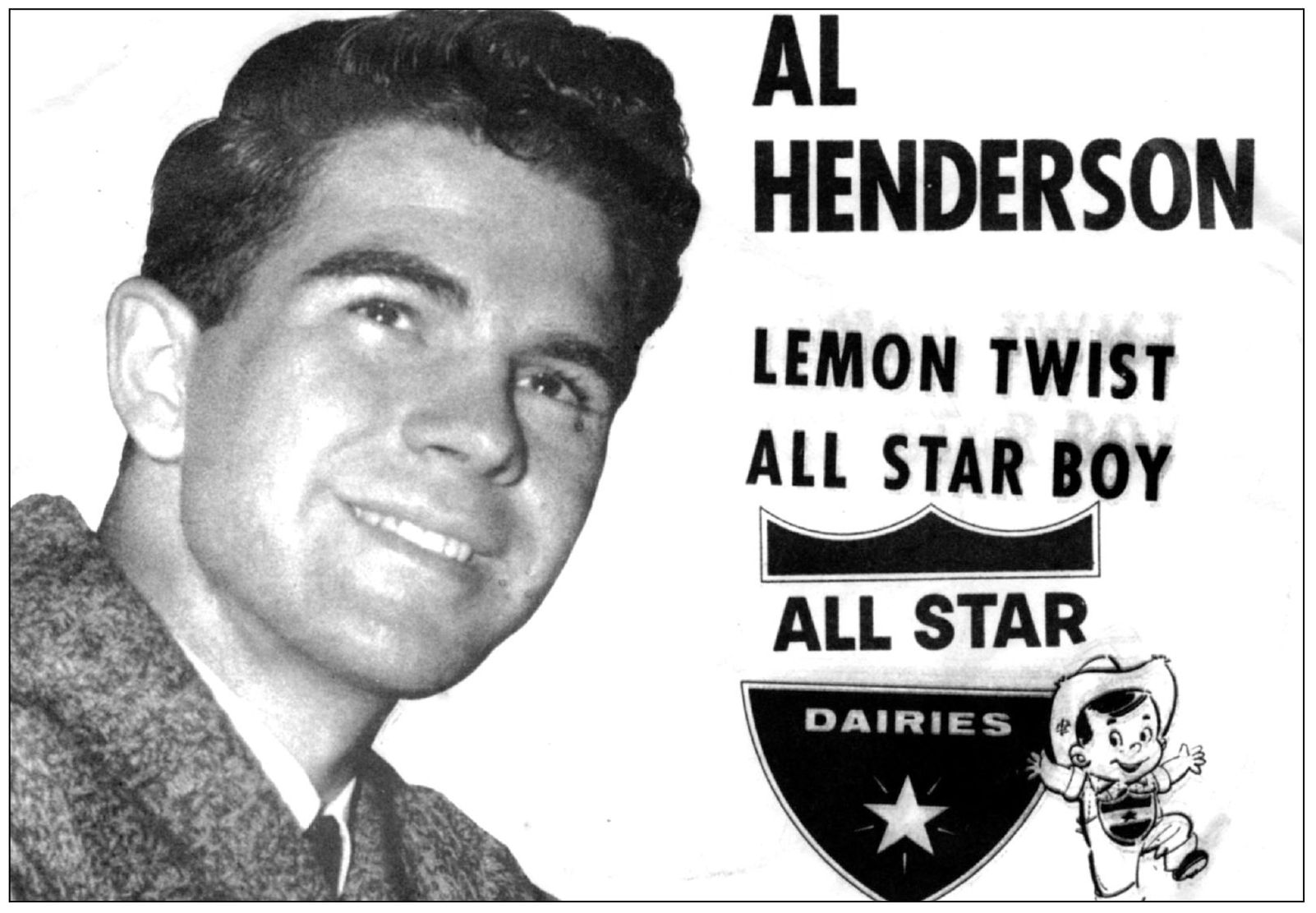

Al Henderson once performed with King Records’ rockabilly band Boyd Bennett and His Rockets. In 1962, he recorded a solo single that was more company promotion than commercial record. “Lemon Twist” was another variation of the popular twist and a type of ice cream from All Star Dairies. Unlike most King Records releases, the single was orange and labeled first edition. (Author’s collection.)

Dale Wright, a Middletown native who recorded in the King Records studio for Fraternity Records, once said this photograph shows his old band, the Rock-Its, rehearsing in the King Recording Studio for a session around 1956. There Wright recorded “She’s Neat” for Fraternity Records. His later group was Dale Wright and the Wright Guys. (Courtesy of Dale Wright.)

Charlie Ryan’s rockabilly songs “Hot Rod Lincoln” and “Side Car Saddle” arrived on the country and pop charts in 1960. They were released on the independent 4 Star Records of California, but King Records distributed the label. King issued Ryan’s subsequent LP, which came at the end of the rockabilly craze. “It was nice while it lasted,” Ryan said. (Author’s collection.)

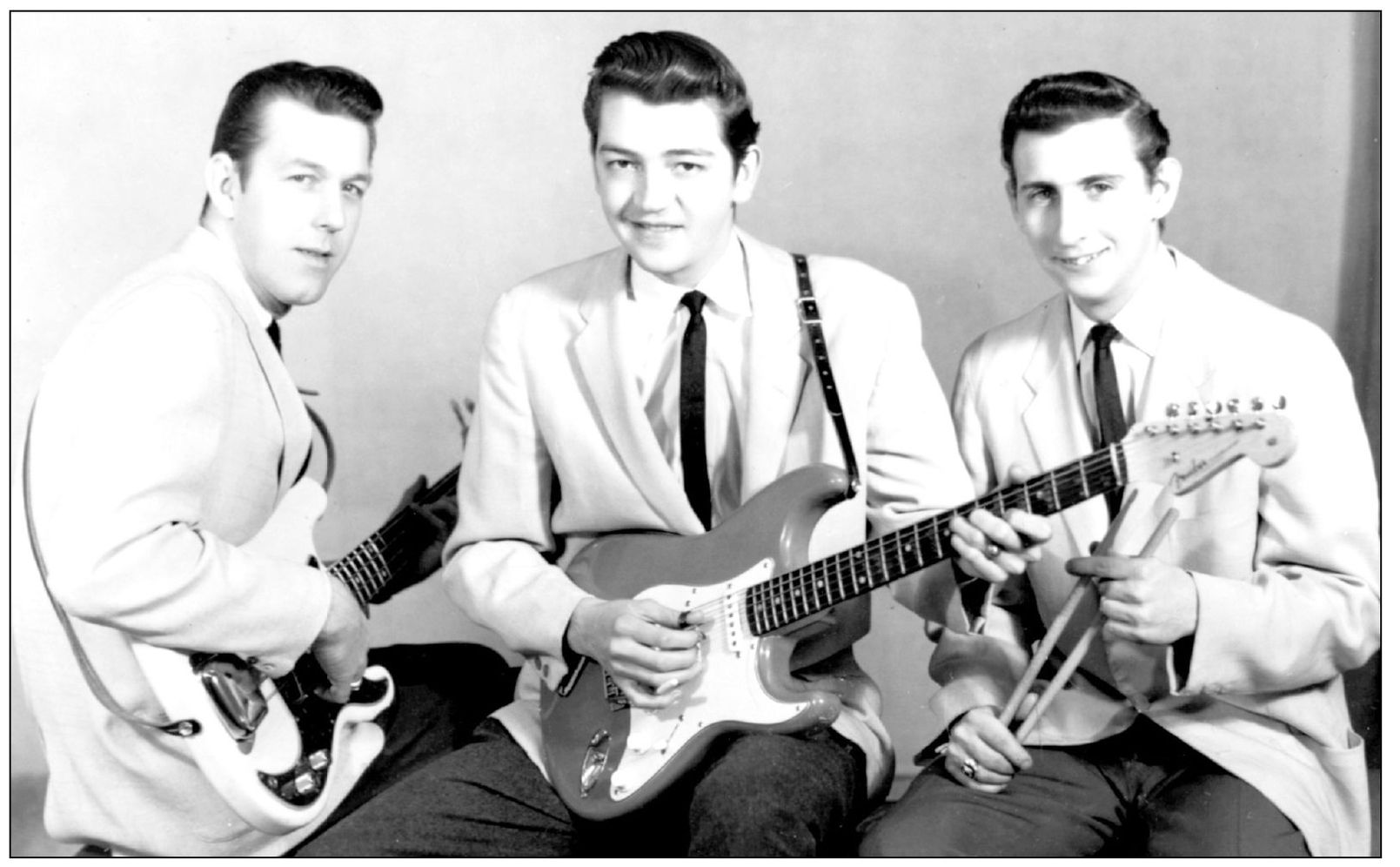

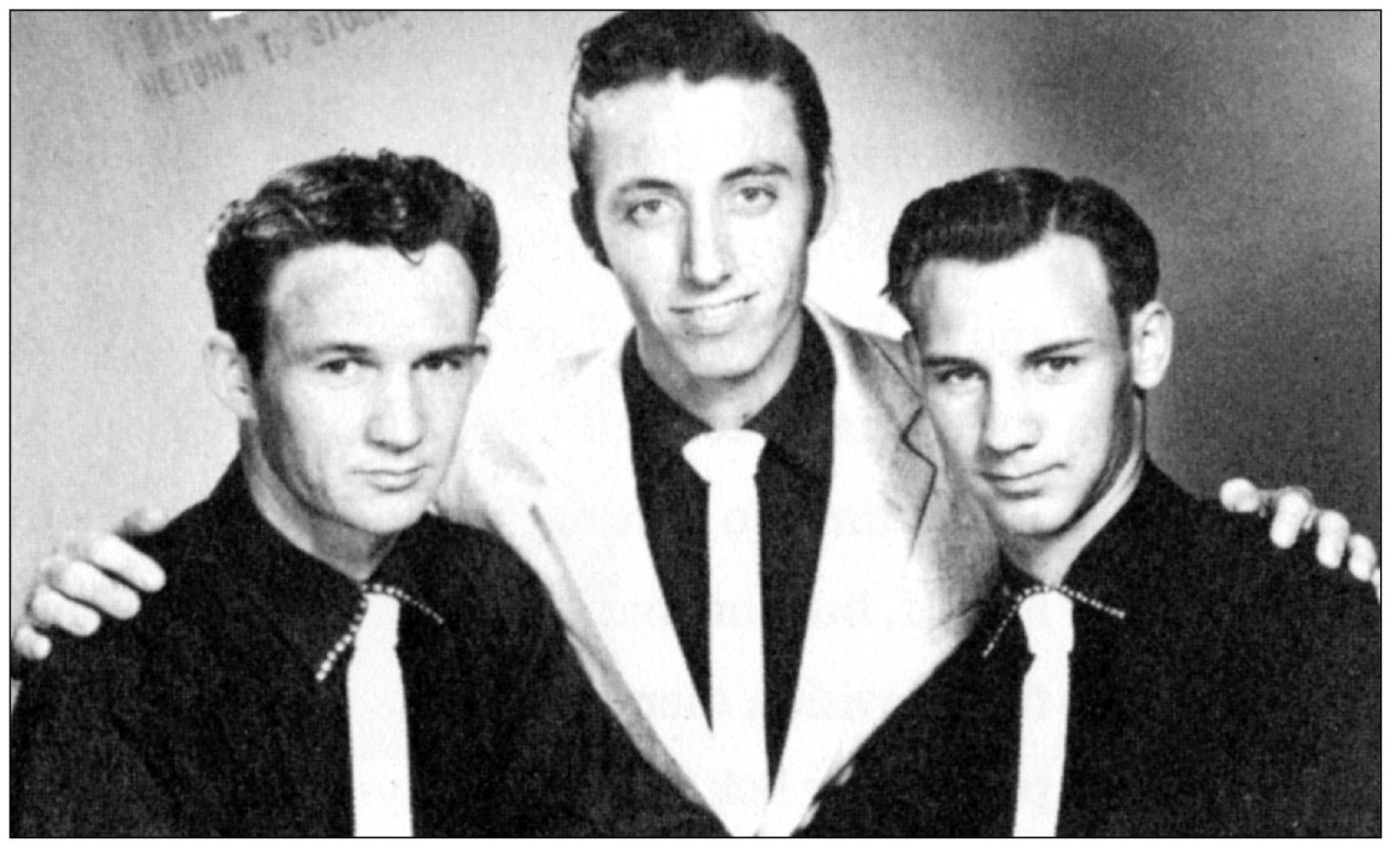

This photograph shows Rusty York (center) with guitarist Hap Arnold (left) and drummer Rick Sticks (right). “A guy from King called me and said, ‘Can you sing like Buddy Holly?’ I said, ‘Oh, sure.’ But I had no idea.” As a result, York covered “Peggy Sue” for King in 1957. In 1961, he cut more King Records rockabilly in “Tore Up Over You” and “Love Struck.” (Courtesy of Rusty York.)

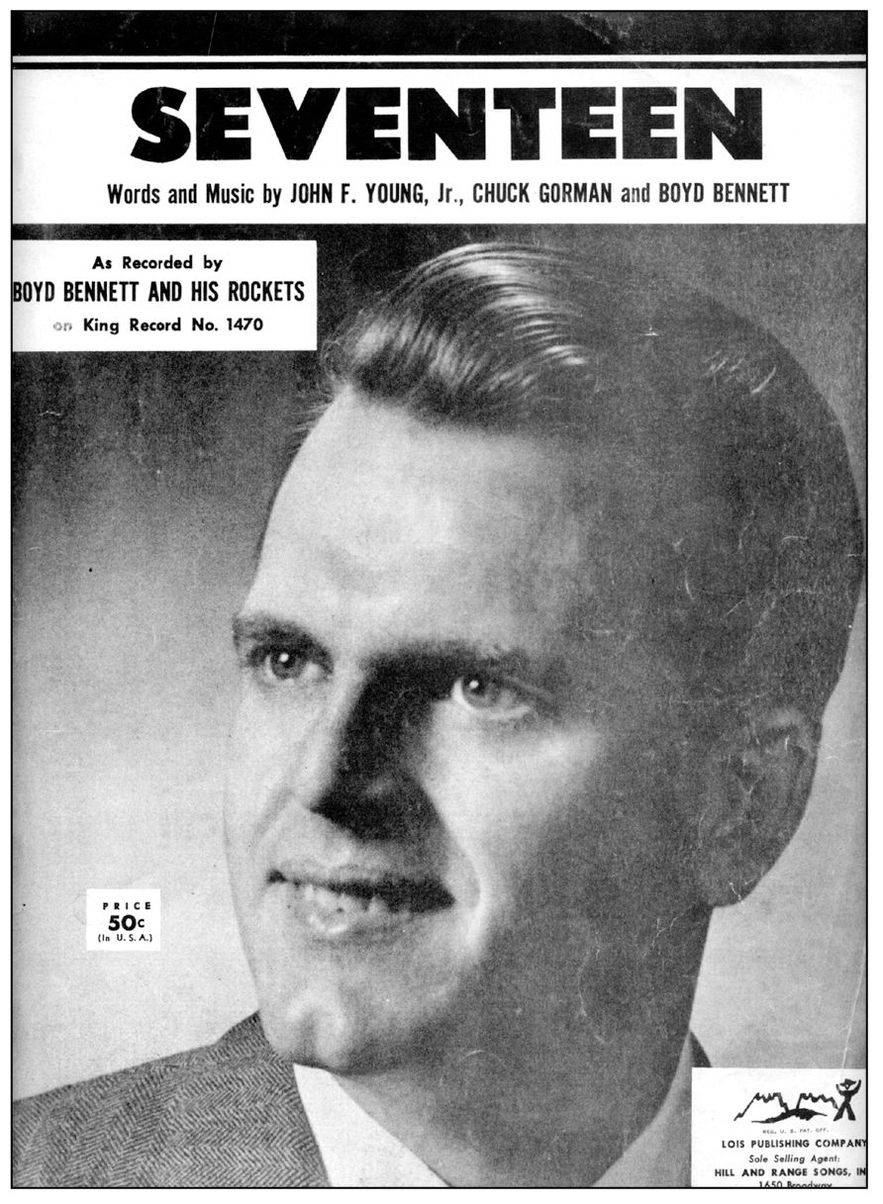

Boyd Bennett and His Rockets exploded with the rockabilly hit “Seventeen” in 1955. He cowrote the song after a colleague at a Louisville television station talked about his 17-year-old daughter. Through 1956, King also issued two other less successful hits by the group, “My Boy—Flat Top” and “Blue Suede Shoes.” But King failed to adapt to the sounds of a fast-changing rock ’n’ roll scene. (Author’s collection.)

Although “Daddy-O” was a national rockabilly hit in 1955, there was a problem—Bonnie was not happy. She considered herself country and so did her audience on WLW-T. Then the station rejected her request for time off to tour and her follow-up singles—some cut in New York—flopped. From July to November 1955, though, King Records rocked the airwaves with “Daddy-O” and “Seventeen.” (Author’s collection.)

Although Bennett’s “Seventeen” sounds hopelessly old fashioned today, in 1955 it was hip, young music. Bennett, a native of Muscle Shoals, Alabama, remained with King Records for a few years before moving on to Mercury Records in 1959, where he had a small chart record called “Boogie Bear.” But even then, rock music had started grooming smoother singers such as Frankie Avalon. In only four years, the evolving rock ’n’ roll sound had grown far beyond Bennett’s upright bass and country feel. Compared with the new rock acts (no more rockabilly for them), Bennett already seemed a musical dinosaur. His King Records single “Hit That Jive, Jack” sounded like music from another world. Bennett’s band recorded most of its music in King’s Cincinnati studio, which limited the Rockets’ exposure to the burgeoning rock scene in New York. Because King’s strength was in country and blues, company executives did not foresee the rapid changes that were coming in rock ’n’ roll. Consequently, Bennett failed to adapt. (Author’s collection.)

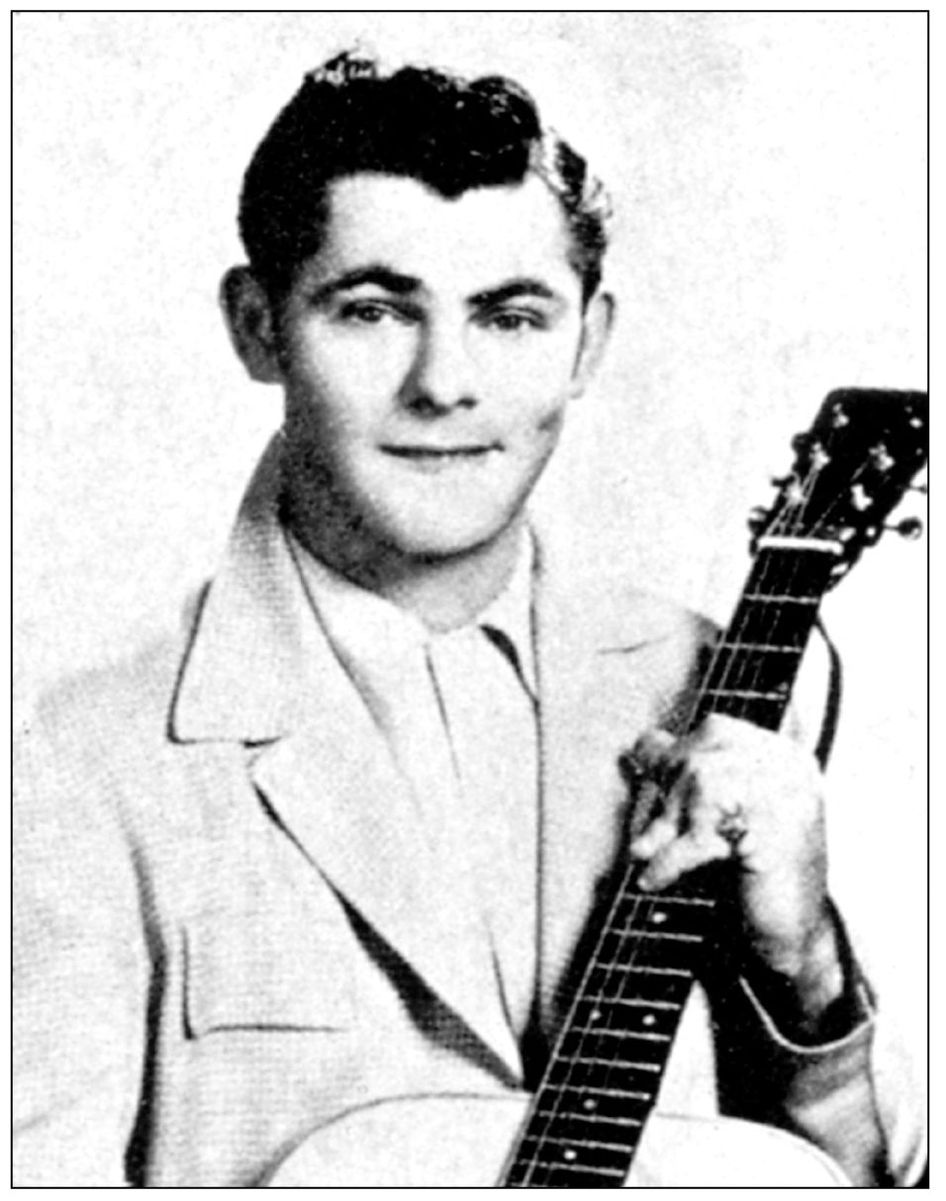

In 1954, Charlie Feathers started recording for Sun Records in Memphis. But King Records wanted him to help fill out a small but expanding rockabilly roster that was inspired by the success of Elvis Presley. Feathers did not make any hits for King Records, but he did record some now highly collectable singles including “Bottle to the Baby.” (Courtesy of Charlie Feathers.)

King Records signed Wesley Erwin “Mac” Curtis (center) while he was in high school. A principal actually came to his classroom to tell him personally that a King Records producer wanted him to record that night in Dallas. “They thought I could be their Elvis,” he said. Mac performed with Alan Freed’s rock shows in New York in 1956. Later he went country and worked in radio. (Courtesy of Mac Curtis.)