JOSÉ SALGAR: Of course Gabo was good, but at that time I also had magnificent reporters, more brilliant and more skillful in reporting. The editorial board of the newspaper would meet to deal with the day’s topics, and say: “Today you go there and cover this,” and give some instructions. But there’s also personal initiative by which it occurs to the reporter: “I’m going to write on this subject,” he proposes it, and you tell him to do it or not to do it. He? Initiative? Not much. Not much. Gabo had initiative for his novels and for the worm of magical realism and literature, but at the newspaper as a journalist he had to march in time with everybody else . . .

At that moment he resisted, but afterward, almost as soon as he started reporting, he grew fond of it. And he grew even fonder when he started writing. It was certainly fast. The paper had to get out, and often I would pull the text out of his typewriter, pass it along to a copy editor for fast correction, and it went out, though a little rough. One of Gabo’s characteristics is not turning in originals with errors. If he has something he has to correct, he tears it up and begins again. His wastebasket was always full of crumpled drafts. He’d repeat the process until he had an original as perfect as possible. Except for some things. Somewhere I have an original that he declared finished but only because he was in a hurry.

MARGARITA DE LA VEGA: He wrote movie reviews. You can look at the articles. Film was a part of the culture. Film clubs were a very important element in the cultural life of the entire country, and that was an inheritance from the French. My father, who studied medicine in Paris and married a Frenchwoman, started the first film club in Cartagena with Eduardo Lemaitre. There were also poetry get-togethers where, for example, Meira del Mar, the Barranquillan poet who died a little while ago, got her start. People met to recite poetry. In Bogotá too, but the idea that Bogotá was Athens and we were idiots is a lie.

JOSÉ SALGAR: Gabo loved articles about film and had written them at El Heraldo. Then he came to El Espectador. What he liked best was writing, and what ended up being a mission for him were the “From Day to Day” notes and movie reviews. Then he discovered something different. It was giving his opinion about something in the arts through his movie reviews. And he also wrote book reviews. He emulated very famous writers like Eduardo Zalamea, Abelardo Forero Benavides, very distinguished men, and at that time those “From Day to Day” notes had considerable importance and allowed him to make a little literature and write well.

I knew what he was doing: I had read his stories and thought he was an excellent writer. The only concrete thing, the impression I always had of him at that time, was that he turned in the best originals I’ve ever received.

First, immensely neat, very hardworking, because he tossed everything he didn’t like into the wastebasket until he came up with a perfect original. I thought that was terrific, but that he needed to apply himself more to the reality of journalism . . . The fact is he had two totally distinct faces. One was his obsession with literature. He was discovering literature; he discovered it with his literature teachers at the secondary school in Zipaquirá. He turned to them for his memoirs. They were obsessed with literature and he was discovering Joyce, all the great writers of the time. Then, at night, he would think of literature as fiction and as beautiful language. He was writing stories.

JUANCHO JINETE: “The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World” was Álvaro Cepeda’s and Álvaro says I was the one who told the story to Gabito. “Sonuvabitch, why did you tell him that?” And I say: “Come on, he got it out first.”

Man, that happened in Santa Marta. Do you know the Santa Marta Bay? In Tasajera, it’s fishermen. The guys there, they go out to fish. Then this guy went out to fish and didn’t come back the next day. On the third day they went out to look for him. Then they began to get together for the wake, and you know you have a wake with rum. Then after five days . . . You know that in those houses the courtyard is right next to the swamp, and out of the swamp, ay, comes the handsomest drowned man in the world. They told it to us there, and then one day Álvaro says: “Aha, Gabo, that’s a great story about the drowned man.” And he says: “Which one is that?” I tell it to him, and wham! he brought it out first. Afterward Álvaro wrote it, but in another form.

Then there’s the story “The Night of the Curlews.” So there in the brothel of Black Eufemia we woke up one morning: Álvaro, Gabito, Alfonso, and I. And since it was like our house because Alfonso’s father was the owner and rented it out, they treated us well. At night they turned the curlews loose.

QUIQUE SCOPELL: It’s a bird like a heron that sings a lot at dawn. Then Black Eufemia, since she ran the brothel, had her twenty women in their rooms. And at night, at two or three in the morning, when the women were going to bed, she would bring out the curlews . . .

JUANCHO JINETE: Into the garden.

QUIQUE SCOPELL: Black Eufemia died. And one of her clients put the whores to work in his factory . . . and this guy, who was a client, said to the twenty whores: “You don’t have to work at this business, you can have a decent life. I’ll take you to my factory to work. You can all be working in my factory.” And he took them. He had a paper bag factory. The man was one of those Christians, full of charity. He had the most altruistic idea in the world. He took them to work and the whores, after twenty days, said: “No, this is as far as we go.”

JOSÉ SALGAR: But in the daytime, when he came and the paper hired him to be a reporter, he had to put all that aside, tell the truth exactly, and have some journalistic parameters that he didn’t have. First, to tell things the right way. Second, to turn things in on time. And devote all his efforts to the paper that was paying his salary. Then I ran into a problem. He would come in with his hair uncombed and bags under his eyes, and then I said to him: “We just can’t work this way, no . . .” The story is that as head of the editorial staff I demanded that he walk the line and come in early, and Gabo said that he came in late because he was writing something or other. “You’re dedicated to something else,” I said to him. “Why don’t you wring the neck of the swan and dedicate yourself to writing journalism? Journalism lets you use literature as a tool.” Then this is what happened. He said: “Well, then I’ll give up literature.” He meant that he heard me and was dedicating himself to journalism. And he began to write very good journalism, but in time I realized he wasn’t.

Here it is, this was in ’55: “For the great José Salgar, let’s see if I wring the neck of the swan. With my friendship, Gabo.” First edition of Leaf Storm, which was a little clandestine.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: I was working in Mexico. I was a photographer. One day Gabo published something very false about me, but very beautiful, saying: “Colombian makes neorealist films in Mexico.” I wasn’t making films. I took some photos of a popular Holy Week, like the one they do here; it was in Reyes, in Ixtapalapa. And he liked it very much. He published a commentary in El Espectador. And I wrote to him, thanking him: “I’d like to meet you.” I was returning to the country, I don’t know, it must have been in ’55. He said: “Yes, I’m at El Espectador.”

JOSÉ SALGAR: Gabo was sent to cover the Vuelta a Colombia, the bicycle tour, and to talk to Cochise Rodríguez, who was the champion but still quite dull. “Talk about the life of Cochise Rodríguez.” Any reporter would say, “What a boring assignment to send me to interview Cochise Rodríguez.” Gabo did it. Damn! He sharpened his pencil and went. As soon as he was given a topic, the man warmed up, would start finding the details and then began to verify things. And once he was writing he remembered more things . . . The thing was very well done even if it was a boring thing like a bicycle tour.

He specialized in writing newspaper series. There’s also that very long story about the department of El Choco. When Rojas Pinilla, president at the time, announced he was going to dissolve it, our reporter there sends a story about a huge protest. But when Gabo arrives, he realizes that the guy had made it up. Gabo actually had to make it happen. The news existed, but no one wanted to talk about it and tell the story about the poverty that existed in that region. He did that.

QUIQUE SCOPELL: Gabo was a normal guy. I think he has a great virtue, which is tenacity. The man is tenacious, tenacious, and for his whole life he wanted to be what he was. A journalist. He’s a great journalist. No, I don’t think I thought so before. But he is.

JOSÉ SALGAR: We sent Gabo with General Rojas Pinilla to cover something in Melgar. When he arrived at the Melgar airport he saw that another plane was flying somewhere else and he said: “Where’s it going?” They told him: “They discovered guerrillas in Villa Rica, in El Tolima.” So he went to Villa Rica and not to Melgar. And he arrived with the photographer and there was nothing there. But suddenly somebody told him: “The guerrillas are there.” And he went and he found the thing and saw that the guerrillas had killed four soldiers. And they were present at the thing. And surely, they brought down the soldiers, but the government, which was Rojas, completely denied it. He couldn’t publish anything. We lived with censorship at the time. Then he was left with the four dead men covered up, and now, fifty years afterward, he’s reliving all that but in detail for his memoirs. He called to ask me facts about it . . . With him, it has to be perfect. A month ago he called me from Mexico to ask me the name of the photographer who had gone with him to something. And on the basis of that we talked about other similar news items. We talked for an hour and a quarter.

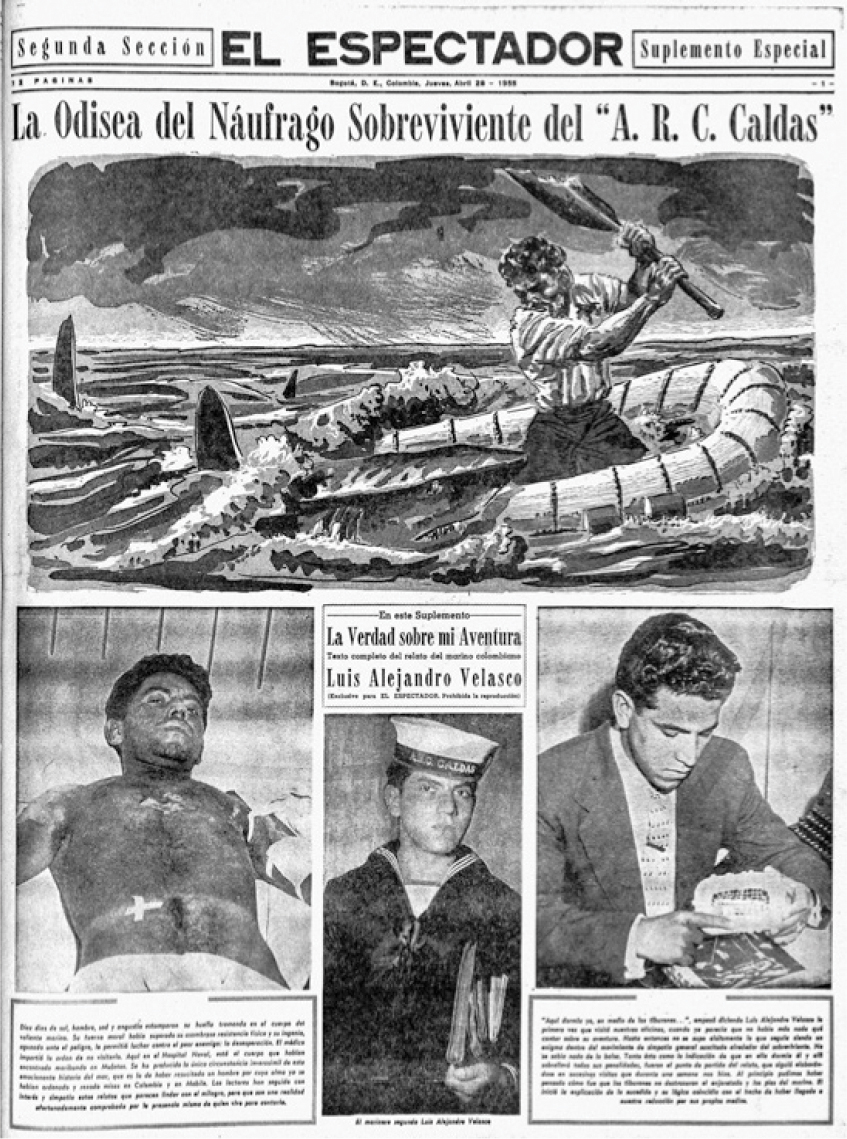

JUANCHO JINETE: He stood out because of that time he reported on the sailors they threw into the water at the naval base. That’s when . . .

JOSÉ SALGAR: There’s the Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor. That was an ordinary, run-of-the-mill piece of news. Big and all that, but the news item was already dead. And the anecdote is very curious. Gabo and Velasco, the shipwrecked sailor, met, and Velasco had already told everything to other journalists, but they met because we told Gabo that it was a question of getting a few things out of him. They met in a café and the guy began to tell him his story and become excited: he suddenly realizes what he’s saying . . . That was the spark that gave rise to the story. That happened with Gabo’s things. But what is it? It’s meticulousness. The journalistic responsibility to find out.

JUANCHO JINETE: There was a shipwreck but no one had figured out that the navy ship was carrying contraband, refrigerators and things like that, and they threw a boy overboard, one of the sailors . . . And that was his scoop. He wrote a feature article and nobody here dared to write a feature about that. Well, first because it had to do with the navy. That boy’s calamity and how he was saved.

JOSÉ SALGAR: The famous Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor . . . He never realized the importance it finally had. It was one of the reasons for the fall of Rojas Pinilla. Because he was writing under press censorship when he went to see the hero, who said some things about his ship tilting when it came in. But Gabo finds out that it wasn’t a storm but the weight of the contraband refrigerators it was carrying. The sailor said it naively, Gabo confirmed it, and published it with the title The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor Who Spent Ten Days Adrift on a Raft with Nothing to Eat or Drink Who Was Proclaimed a Hero of the Nation, Kissed by Beauty Queens and Made Rich by Publicity, and Then Abandoned by the Government and Forgotten Forever.

RAFAEL ULLOA: The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor made him famous. Rojas Pinilla was going to have him arrested.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: The fact is there’s nothing like dictatorship. Look, Rojas Pinilla called Fernando Gómez Agudelo because Fernando’s father was a great jurist. They called him “Toad Gómez” and he was the one who resolved Rojas Pinilla’s legal problems. Then, as a gift, they allowed his boy, who was twenty-two, twenty-three years old, to introduce television in Colombia. Rojas said to him: “You’re going to set up television, but it has to be ready within a year, when it’s the anniversary of my government.” Then he went to the United States and told them about the problem of television in Colombia. They told him: “That’s impossible, in a place with so many mountains, you can’t have television.” Then he went to Germany. In Germany they told him yes, but it was very expensive. “You have to have booster antennas on each mountain and you can bring television wherever you like as long as you have money for booster antennas.” And he said: “Let’s go.”

There were just a few days to go and the sets arrived, the last ones they needed, from Germany on a KLM plane. And the director of Civil Aeronautics said: “That plane can’t land.” “Why?” “Because we don’t have an aviation agreement with Holland.” Then they call Fernando and tell him: “No, the plane is going back.” And he says: “Just a moment. Tell the plane to fly around and I’ll settle this in ten minutes.” He calls Rojas Pinilla and Rojas Pinilla tells him: “Listen, I am too busy to deal with this. You call the director of Civil Aeronautics. Tell him that if that plane isn’t on land in five minutes, he’s fired and you’ll become the director of Civil Aeronautics and you settle this.” And that’s what happened. There really isn’t anything like dictatorship.

HÉCTOR ROJAS HERAZO: And then came his desire to leave for Europe. El Espectador sends him.

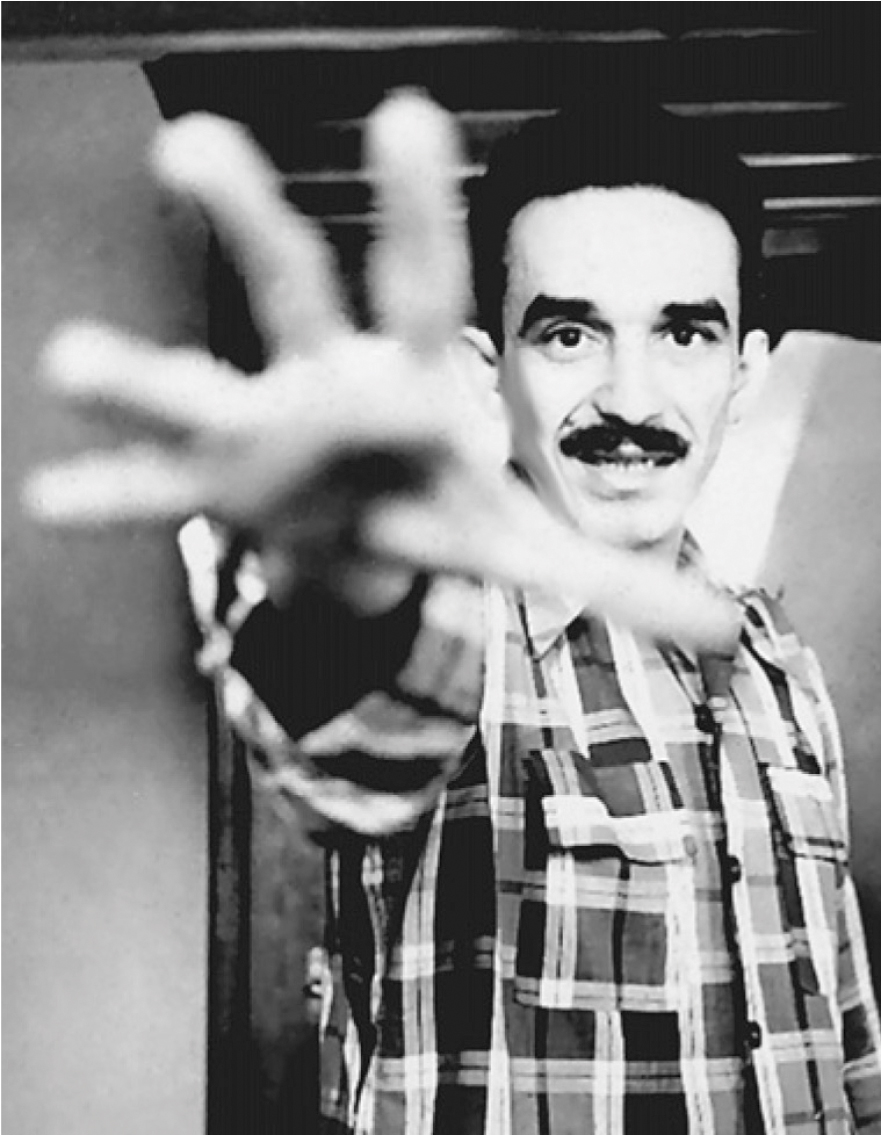

In Paris with an open hand, taken in 1954.