EDUARDO MÁRCELES DACONTE: Aracataca has about five thousand people. I don’t know how many, but a lot of people there have read the novel. Well, reading is more emotional when a person can recognize things. Perhaps in another person it would be more intellectual. But I’m referring to the case of someone who recognizes the town, the place, and the people, isn’t that right? There’s a more emotional relationship, even a sentimental one, if you prefer . . . For the people from there many of the things are no surprise; in fact, for the people from the Coast. You know, we exaggerate a lot of things, and we say things, many things that, well . . . So I think things are taken more naturally.

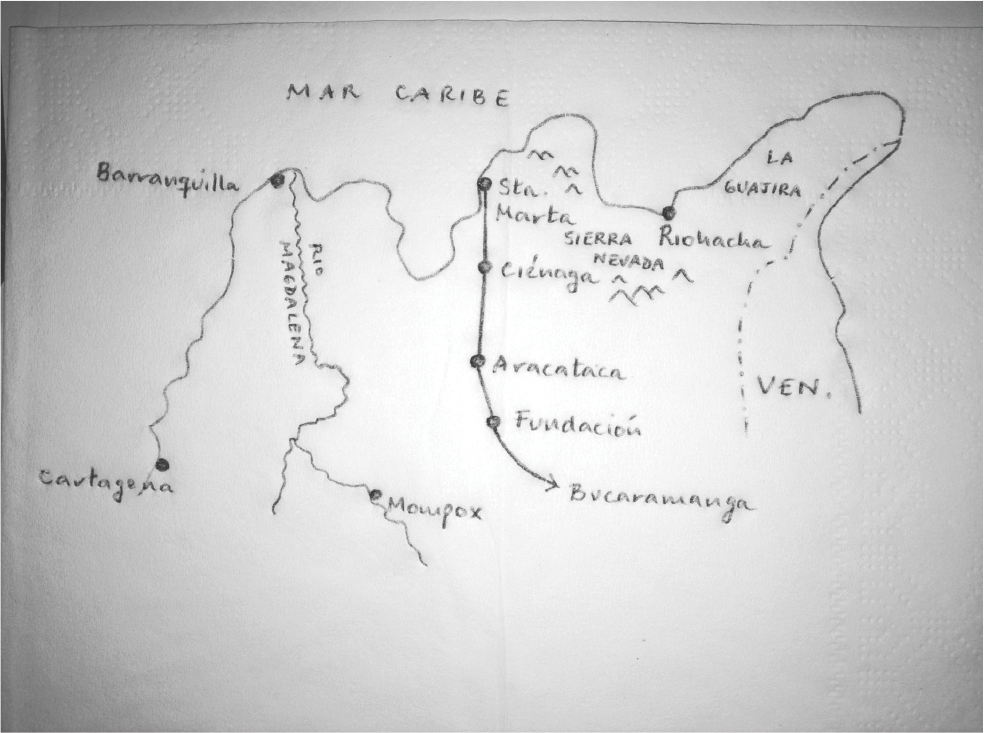

Let me draw it for you here on this napkin. This is the coast: here’s the Magdalena River, here’s Barranquilla. Santa Marta is here. All this is the Sierra Nevada. Then Aracataca is here. Fifty miles to the south is Aracataca. It’s on the spurs of the Sierra Nevada. The Magdalena River. Here’s Fundación and here’s the road to Bucaramanga and the interior of the country. Do you see? According to this, Mompox is more or less here, on the banks of the Magdalena River that comes through here. The departments of Atlántico and Bolívar are here. Riohacha is over here.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is from the river to here, from the Magdalena River to the east, the northeast of the coast. That is, everything that would become the region of Santa Marta, Ciénaga, the banana zone, and then from the Sierra Nevada to Riohacha, which is where the founders of Macondo come from. You know that Aureliano Buendía killed Prudencio Aguilar in La Guajira; then there’s a kind of exodus, and the ones who leave are the ones who found Macondo. He takes this from his grandfather’s story.

PATRICIA CASTAÑO: On the trip we made to retrace the journey of One Hundred Years of Solitude, his English biographer Gerald Martin and I went from Maicao to Barrancas, Guajira, which is an important town today because of the coal mines in El Cerrejón. It must have had something then as well because Colonel Márquez left Riohacha for Barrancas. I think it was an area of colonization, like an opening of the frontier. And it must have been a town rich in cattle, maybe. Then we go there looking for the history of the family, the arrival of Colonel Márquez in Barrancas. And Doña Tranquilina doesn’t arrive right away. That is, he goes first. Then when Doña Tranquilina comes and they move into the house, he’d already had a series of lovers (it seems he was dreadful). And one of those lovers seems to be Medardo’s mother, who was a lady of rather easy virtue.

Map of the region that was originally Macondo.

We interviewed a lot of people there who were either relatives or who knew the story. In other words, that history and its relationship to the town is very vivid. Here’s something very interesting. We met a little old man, very very old, who says he witnessed the death of Medardo. He says he was very little, a boy of seven or eight, and at that moment he was delivering something. He reached the corner just as Colonel Márquez fired his revolver and killed Medardo. But the marvelous thing about the oral tradition is that on the night we were there in Barrancas, on the street, on those benches that rock back and forth, and the granddaughter of one of the ladies, who must have been about twelve years old, showed up and said: “My grandfather told me the story of that death.” And then, standing in the middle of the street, she began to recount the story, and you can’t imagine how delicious it was.

I don’t know why I didn’t have a camera with me. Well, at that time cameras were very heavy: “And then Colonel Márquez was waiting for Medardo. He knew that because it was the day of the town’s patron virgin . . .” Medardo lived on a farm. “He would come with feed for the animals because he was going to stay there for a few days, for the fiestas. The colonel said to him: ‘I have to kill you, Medardo.’” And then Medardo said something about the bullet of honor, I don’t remember. But the girl told it as if it had happened yesterday. I think it’s in Gerry’s book, but what impressed me was the oral tradition. This little girl. It was as if she were narrating Euripides, as if she had learned it by heart in a book. That really impressed me because it happened in 1907 I think, and in this town, in 1993, the story was still alive.

EDUARDO MÁRCELES DACONTE: Even though Aracataca is hot, it’s a town that’s on the spurs of the Sierra Nevada. That’s why it has “a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs,” as he says in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Why? Because it’s a river that comes from the Cristóbal Colón and Simón Bolívar snow peaks. It’s the Frio river, the Fundación river. It’s hot, but at the same time, at night the weather’s cool because of the mountain and the rivers and streams that come down from the Sierra. The vegetation’s very dense. In other words, it’s really beautiful around there.

There’s a dry season and a rainy season, the typical climate along the coast. So if you go there in the dry season, you’ll see that it’s dusty. But it had to be rainy because bananas need a lot of moisture. When there are rainstorms, they’re tremendous downpours, like the ones in “Isabel Watching It Rain in Macondo,” which are interminable.

All of Aracataca is in the novel. There’s the river of crystalline water, the Aracataca River, a really beautiful river. Because it’s like this: it has little beaches. And almond trees. Almond trees all around the main square in Aracataca. There’s the heat. The afternoon siesta. There are all the people who travel through Aracataca, which is a travel center. It’s the place the Indians from the Sierra Nevada come to. Many people passing through. There’s the train. And, well, ideas. For instance, during the banana bonanza in Colombia, people danced the cumbia using bundles of bills as candles. That’s in the novel.

You realize that in Gabo’s narrative the environment has a great deal of influence. Superstition plays a great part. Things of those towns. Natural phenomena. The rain. The heat. They had to have that influence. And you know that the rainstorms there can last two or three days, when it seems that pellets were falling from the sky because they’re downpours, rivers, and that must have had a big influence on him. He begins to absorb all these things that happen around him while there are natural phenomena with tropical intensity. Aracataca didn’t have electricity until a short while ago. It had a small generator.

All of this area that goes from Ciénaga to Aracataca to Fundación, all of this is the banana zone. It’s very fertile land because it’s the alluvial deposit from the mountains that comes down to this little valley, a broad valley. Aracataca was an agricultural town. It was beginning to see the inroads of bananas. All the banana plantations were here in this region. At first the owners lived there, there were plantations.

My grandfather, Antonio Daconte, comes there from Italy, and he’s an impressive figure in the town. He opens a store that was called Antonio Daconte’s Store. He isn’t just anybody. My grandfather emigrated from Italy toward the end of the nineteenth century and came to Santa Marta. He was one of the first colonizers in Aracataca; he comes there and practically helps to found the town. When he arrived, and when the Turks arrived, and the Italians, Aracataca was barely a tiny hamlet.

IMPERIA DACONTE: Three young siblings arrived: Pedro Daconte Fama, María Daconte Fama, and Antonio Daconte Fama, who remained in Aracataca. Very young people when they arrived. Things went very well for him in Aracataca. Oh yes. He had three farms there. And most of the houses in Aracataca belonged to my father. He traveled to Europe, my father. The rest didn’t travel.

EDUARDO MÁRCELES DACONTE: He arrives, and I don’t know, either he brought money with him or made some deals that went very well, because from the time when he arrives he sets up a tremendous store and organizes the movie theater. He had one of the biggest houses on what they call Four Corners, which is, in a manner of speaking, the Times Square of Aracataca. It’s called Four Corners. It was an immense corner house. It took up a quarter of a block, I’d say, because in the courtyard is where he set up the theater. The movie theater. In the courtyard of his house. There were chairs, and he brought the machines, and then by train they sent him films from Santa Marta. He had his people who fetched and carried, and there was a projectionist and everything. He brought the movies and the jukebox. All the new things that were appearing, he brought them to Aracataca because he would travel to Santa Marta.

IMPERIA DACONTE: My father would take us to the farm very early so that we’d have the morning air. There were a lot of bananas and they would fall, then they would cover them up and I would pick from this bunch and then from another.

EDUARDO MÁRCELES DACONTE: Later on the United Fruit Company arrives, and it acquires many of the farms. Although all the original owners were kept on, United Fruit is practically turned into a banana monopoly there. They’re the ones who buy the bananas, process them, export them. They have their own ships.

RAMÓN ILLÁN BACCA: But of course moving up wasn’t so difficult at a given time because all the people came and set up a store and then bought land. The value of land increases again in ’47, after the Second World War. And people found themselves rich. That’s what they call the banana bonanza. My aunts, the Nogueras of Santa Marta, had been rich from before.

ELIGIO GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ: In order to protect top management, the United Fruit Company had built its encampments, far from town, in the middle of the plantations. The one in Aracataca was a kind of neighborhood called El Prado, wooden houses with burlap windows with wire gauze as a protection against the mosquitoes, and pools and tennis courts in the middle of an unbelievable lawn. And so, on one side, separated by the train tracks, in the middle of the coolness of the plantations, the citadel of the gringos, the “electrified chicken house” as García Márquez calls it, immune to heat and ugliness and poverty and foul smells. On the other side, the town. With wooden houses and tin roofs or simple cane and mud huts with straw roofs. The town where, attracted in a certain sense by the bonanza, the Márquez Iguarán family had come to live in August 1910.