GUILLERMO ANGULO: Gabo invited Fernando Gómez Agudelo and me to a party, and we went from Bogotá to Mexico City via New York. We were in a cab in New York when they announced that the Nobel Prize in Literature had gone to Gabriel García Márquez. We didn’t hear it clearly, did we? We didn’t believe . . . That wasn’t in the range of the possible. Then we changed the station and they confirmed it.

FERNANDO RESTREPO: Do you know the story about Alejandro Obregón, when he went to restore a painting of his in Gabo’s house in Mexico City? Well, in Gabo’s house we saw the famous painting, which is by Blas de Lezo, the Stubborn Man*. The story is that one day he goes to Alejandro’s house in Cartagena, and after a few rums, I don’t know why, at a certain moment (I heard this personally from Gabo when he showed us the painting in his house in Mexico City) he takes out the rolled-up canvas and it’s of Blas de Lezo, “Cool Dude,” with a hole from a bullet that he [Alejandro] shot in his eye. And he says that it was because his children began to fight over the painting, disputing who owned the canvas, and in a fury he shot out the good eye in the painting. I believe Alejandro had a certain obsession with blindness; I think his father had a vision problem. At a certain moment he says to him: “I don’t want that damn painting. It’s for you.” And he raises his hand, like this, “For Gabo,” and he gives it to him. Gabo leaves very happily with his painting. And he has it the whole time. Obregón promised to restore it for him, but he never did. And one fine day Alejandro goes to Mexico City.

JUANCHO JINETE: There’s a good story. I don’t know whether you’ve heard it. When Maestro Obregón was at the filming of the picture Quemada in Cartagena, this man who was Marlon Brando wasn’t going around with anybody. You know those guys are strange, and he saw Maestro Obregón in some scenes. He came out on a horse. He was a nobleman with his sideburns. Then he met the maestro and they became friends. Afterward Marlon Brando would go every day to the maestro’s house to drink white rum. What was the name of that rum? Tres Esquinas.

The filming continued in Morocco, and when he was on his way back, Gabito told him to stop in Mexico City. He was coming by way of London, and he made all the connections and arrived in Mexico City. So the address he had for the house where he lived, where the rich people lived, the movie stars in Mexico City . . . Well, long story short, a house he had. So the maestro took a taxi, arrived there, and saw the terrace of the house filled with flowers and things. He arrived and said: “Damn, he died.” Those flowers were the ones used for tributes. That’s a good story. And when he arrived here in Barranquilla, that was the first thing he told me: “Juancho, listen to what happened to me. When I’m ready to get out I see all these flowers and think he died. ‘Shit, he died.’” It was the day they had given him the Nobel Prize.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: When we arrived, well, the party was in full swing, and we wondered (Gabo always denied it) whether he had known earlier. Yes, he invited us to a party, but his insistence was far bigger than an invitation to a regular party. It did seem as if he had known.

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: I find out because friends call me from Spain saying they had heard the news. They call me from Spain at about four in the morning here. Then I put on pants and a sweater and I rush out to his house. When I get there Mercedes has all the phones off the hook; she’s talking. “Here comes the woman One Hundred Years of Solitude is dedicated to. Talk to her.” She’s holding the telephone so that we can hear what they’re saying. On a big sign on the door of their house, here in Pedregal, they had written in yellow: CONGRATULATIONS, GABO. His eyes were shining.

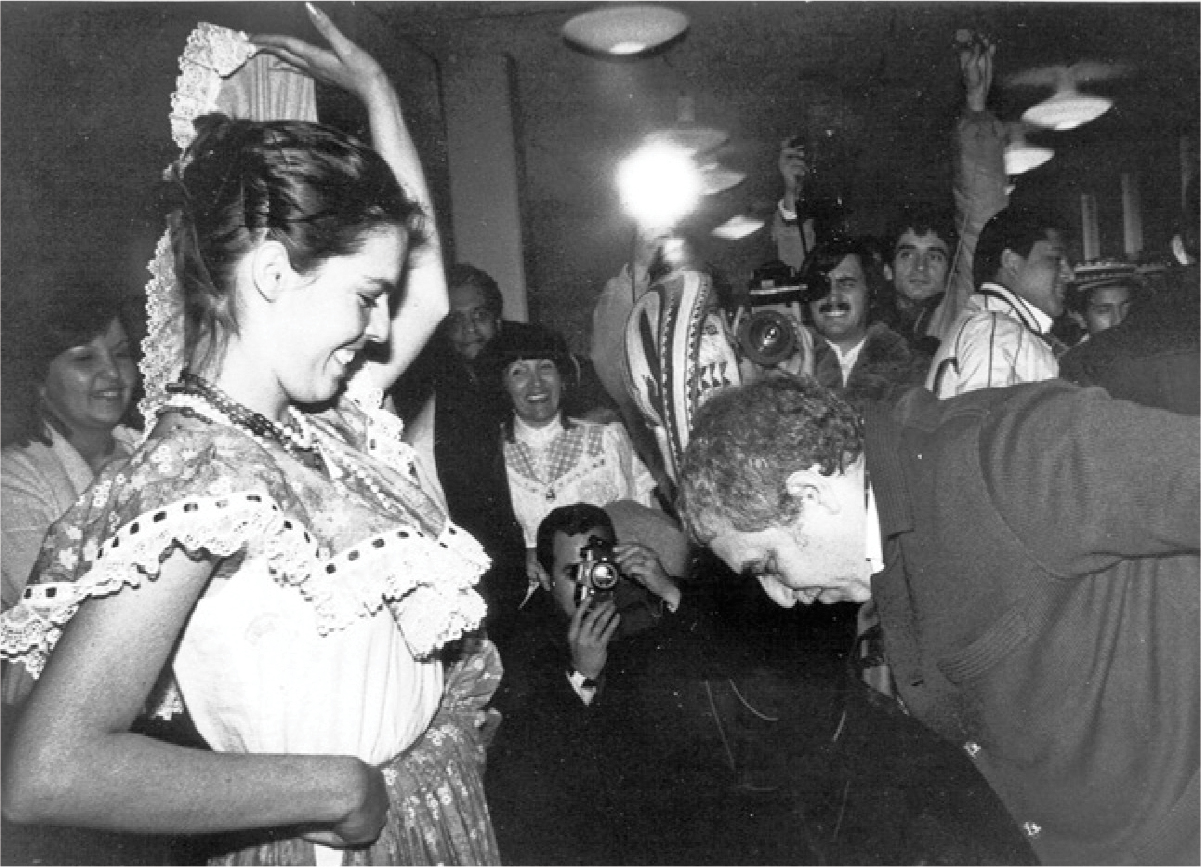

García Márquez greeting a cumbia dancer in Stockholm.

* Blas de Lezo, the “Cool Dude,” is a folk figure in the Caribbean Coast. A Spanish admiral during colonial days, he is known for his victory in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias in 1741 when Colombia was part of the Spanish Viceroy and for all his missing body parts. He arrived in Cartagena having already lost his left eye, his left leg, and use of his right arm and is known as Half-Man. Alejandro Obregón loved Blas de Lezo’s heroism and loved to exaggerate when recounting his version of the one-eyed admiral’s resistance to the siege commanded by British admiral Edward Vernon. “Because of him,” a Colombian saying goes, “we don’t speak English.” When Obregón painted his portrait, he wrote in the left-hand bottom corner: “Blas, the cool dude of Lezo, half a gaze and half a hug, seven balls and seven seas bringing victories and gangrene. A bullet hole for history and a silence made of copper for Blas de Lezo.”