GUILLERMO ANGULO: [The then president] Belisario Betancur told him: “Make a list of your eleven closest friends so that they go with you to Sweden,” and he said: “No, then numbers twelve and up are going to hate me. So I won’t do that.” Then I said: “Mr. President, it is up to you to do it,” and he said: “I won’t do it either. You take care of it.” And I did. I chose the ones I thought were Gabo’s best friends and we took them, at the government’s expense.

GLORIA TRIANA: I was the one who coordinated the delegation of musicians who traveled to the celebration of the prize. The idea came from Gabo, though he surely said it not thinking they would do it but just as a way of expressing himself. “I don’t want to be in Stockholm by myself. I’d like to have cumbias and vallenatos with me,” was what he said. I went immediately to the director of Culture, what’s called the Ministry of Culture today, and I said to her: “If he says he wants this, then let’s organize it.” The boss, Consuelo Araujo Noguera, chooses the vallenatos and the rejection begins; our ambassador in Sweden thought it was terrible that we were going to do that. That was playing the fool, acting like an imbecile. There’s an article by a Colombian reporter, D’Artagnan, who’s dead now, called “An Act of Silly Tackiness.” He used the Bogotan popular slang, “hacer el oso,” which means to do something embarrassingly tacky, uncouth. So that was the attitude of people except for Daniel Samper, who defended the idea.

NEREO LÓPEZ: The director of Colcultura, Aura Lucía Mera (we called her la Mera) tells me to go as the photographer for the delegation. And so we went. And so we got there. Certainly very late. We left Colombia at about five. One hundred and fifty people in the delegation. Folkloric groups. La Negra Grande. Totó la Momposina. A group from Barranquilla. A group from Valledupar. Special guests went by another route. It was in December ’82 that we went.

RAFAEL ULLOA: The old man, Gabriel Eligio, Gabito’s father, loves to talk. In Cartagena he always went to the park to talk to people and there they congratulated him. But more than anything he was a simple man. He’s not like Gabito. Gabito threw a dimwitted party with that Nobel Prize thing, taking even vallenatos groups there with him. Well, they were extravagant with strange things.

QUIQUE SCOPELL: It was a few people. They suggested I go but I said: “No sir, I’m not spending all that money, what did you think!” Alfonso went. And Germán went.

JUANCHO JINETE: Álvaro had already died.

NEREO LÓPEZ: In any case we reached Stockholm at dawn. It was so cold!

QUIQUE SCOPELL: They brought along some vallenatos. The ones who wrote those songs about yellow butterflies, lying vallenatos, lies to sing there.

NEREO LÓPEZ: They told the vallenatos that Swedish women were very loose and so the men were ready to devour all the Swedish women they ran into, and on the third day one of the men says: “They haven’t called us yet.” So that night we went out. Seeing that the mountain didn’t come to us, we went to the mountain. To some damn striptease! Striptease for nuns. There was more covered up, a little bit of nipple uncovered, and that was it. Then the vallenatos said: “No more of this!” We were there for something like two weeks.

After two or three days the folkloric groups rebelled because they took us to eat in a typical Swedish restaurant. That is, food full of fat for the cold. Codfish. And these people used to yucca, plantains . . . they didn’t like it. So they rebelled. A real rebellion. So much so that they had to give in to them. “What do you want?” [they asked them]. They said: “No, we want the money for food.” So they gave them the money. Then they ate hamburgers . . . I was with them and we were living on a boat. It was nicely fixed up and cheaper, because the special guests were staying in a first-class hotel.

PLINIO APULEYO MENDOZA: I see the Grand Hotel, its huge façade with flags waving up high. I see corridors carpeted in purple: a suite as big as a royal chamber, its high windows looking out on the Nordic night. I see thin slices of smoked salmon and disks of lemon on a tray, bottles of champagne chilling in a metal bucket, and beautiful, large, fresh roses; yellow roses exploding on every table above porcelain vases. In the middle of the salon I see Gabo and Mercedes, calm, unconcerned, talking, completely removed from the coronation ceremony that’s approaching, as if they were still in Sucre or Magangué on a Saturday afternoon thirty years earlier, in the house of Aunt Petra or Aunt Juana.

GLORIA TRIANA: As an official I had an allowance for staying in the Grand Hotel, where everybody was, but I was responsible for sixty-two people. I had to pay attention to all those Colombians who had been against it and report on our foolishness.

NEREO LÓPEZ: They asked me where I wanted to stay and I was interested in being with the folkloric delegation. My roommate was the doctor. So the doctor told me that one night a girl from Barranquilla came up to him and says: “Listen, Doctor, now when we get to Barranquilla you’ll give me a laxative so I can get rid of all this junk I’ve eaten here.” And a man from the plains comes and says to me:

“Don Nereo, you up there . . . I don’t know. I want to go back.”

“Go back? Do you know where you are?”

“No, I’m going no matter what.”

“The plane took twenty-four hours to get here. Look. Remember that the plane left Bogotá at five in the afternoon and we arrived here at two in the morning. Look at how far we’ve traveled. And we got here at two in the morning. That means eight in the morning in Colombia. Why do you want to go?”

“No, it’s just that I have a problem. And I want you to resolve it for me and talk to Doña Aura Lucía.”

“And what’s the problem?”

“No, it’s a men’s problem. Well, I go out to urinate and I don’t find my willie.”

“Well, and where do you go to urinate?”

“No, I go to the deck.”

Of course, the deck with one or two inches of snow.

“Find the bathroom, that’s why it’s hiding from you,” I tell him. “And what’s the problem? That happens in the cold.”

“No, it’s that . . . How will I go back to my country if I have . . . three wives there. How do I respond to them?”

“No, man, for God’s sake, the very idea. No. Look, there’s a bathroom down here.”

“No, but I’ve taken off all those layers of clothing and I don’t know where they are.”

Then I had to take him to the bathroom. He wanted to go back! Another case I remember was in that restaurant. Just imagine, winter, heavy food. Suddenly the woman at the counter screams. A scream. Nobody understood. The only thing we understood was the scream. Well Rafael Escalona was going to take a glass of what apparently was fruit juice and it was what they put on salad. The dressing. In a glass. Escalona thought it was juice. First, the harm it could have done him, and then . . . he’d ruin the salad we were all going to eat! Then Escalona said: “What happened?” Somebody said to him: “Don’t you see that you’re drinking the salad dressing?” Aracataca came to the world! They were expecting the Nobel Prize winner but they weren’t expecting a show. The entire nation arrived. They didn’t know where to put the show.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: One of the two Nobel speeches wasn’t written by him but by Álvaro Mutis. He wrote the official speech, but the other one, which might be something about poetry—I can’t really remember—Mutis wrote because the moment arrived and there was no time. Gabo told him “You write it.” Yes. The man sat down and wrote it. Afterward he told the story. I knew that as a secret and I didn’t tell anybody until I saw that Gabo told it one day.

PLINIO APULEYO MENDOZA: In Suite 208 of the Grand Hotel there’s an atmosphere of great preparations . . . It’s three in the afternoon, but the cold night of the Swedish winter, peppered with the lights of the city, colors the windows black . . . A photographer has come exclusively to take the picture of Gabo with his friends. And it’s at that moment that Mercedes remembers the yellow flowers. When she begins to put them in our lapels. “Let’s see, compadre.”

I know the secret reason for that ritual. Gabo and Mercedes believe, as I do, in what is called pava, what I explained earlier . . . There are adornments, behaviors, individuals, articles of clothing that are not worn for this reason, kind of superstitious reasons. Tails, for example. That’s why Gabo decided to wear a liquiliqui at the ceremony, a traditional suit in Venezuela, and in another time, throughout the Caribbean . . .

And now Gabo’s friends, who came to Stockholm to have a photograph taken with him minutes before he receives the prize, have arranged ourselves, our backs to the high windows. Mercedes officiates at this rite too. “Alfonso and Germán beside Gabo,” she has said, referring to Alfonso Fuenmayor and Germán Vargas, her husband’s oldest friends.

GLORIA TRIANA: He was wearing a liquiliqui and not tails. He was the one who gave the most poetic and beautiful speech heard at the Nobel prizes: “The Solitude of Latin America.” He was the one who had a banquet party in the Royal Palace accompanied by all the musicians.

NEREO LÓPEZ: The banquet was where that presentation took place. The nice thing about the dance at the banquet is that with so many people, the chief of protocol was worried. Naturally permissions were required, but the guy who organized all of it dedicated himself to having a good time. He picked up a sailor somewhere. He enjoyed his sailor and forgot about the rest of the world. He didn’t look at my credentials. Then I had to disguise myself as a dancer to go up onstage. And the detectives saw. What kind of dancer is this who goes around with a camera hanging around his neck! The day of the banquet. The presentation of the prize was in the morning and the banquet was at night. The show we had prepared was two hours long. And then the guy said: “Come here, this isn’t on the program. You can’t do this.” Another one said: “You can’t place that cable. Because the King (they’re like gods), the King can’t see the cable.” The King can’t see . . . And on and on: the King and the Queen this, the King and the Queen that, like gods. And the spectacle can’t last more than fifteen minutes.

When they come down those steps with the drums thundering . . . What an emotional thing! But really emotional! The spectacle they had given fifteen minutes to lasted forty-five. Because these guys applauded like madmen, like madmen. Very emotional. Very emotional. So much so that the guy who had put pressure on us said: “This isn’t programmed either but the King has ordered us to invite you to lunch and have the palace cook hurry up and prepare lunch for one hundred and fifty people. So please excuse us.” They gave us a meal and these guys are begging our pardon. They gave us a lunch much better than anything we could dream, of course, but for them no, they were apologizing for its simplicity. But the King, the King had them attend to us. That was very emotional. Very emotional.

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: When they give him the Nobel I’m in my house. My son Diego is in their house with their son Rodrigo. They’re watching television, they’re seeing the Nobel. I’m in my house talking to them on the phone, my son Diego and his son Rodrigo and I are watching at home in Mexico City. I was crying like a hysteric.

GLORIA TRIANA: The next day the most important paper in Sweden had a four-column headline: GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ’S FRIENDS SHOW US HOW TO CELEBRATE A NOBEL.

NEREO LÓPEZ: Rafa [Escalona] was with us. Gabito couldn’t get out of the celebration. He was a prisoner of the moment. He went to all the dance presentations the delegation was doing but they were part of his organized agenda. When we were having a short party, he joined in for a while. We couldn’t really party with him. I bumped into him, for example, in the cumbia. “What happened? What’s up?” and he took me by the chin. “This goatee? How long have you had a goatee?” I haven’t seen him since.

GLORIA TRIANA: The next day all of the international press went to the ship except the Colombians. D’Artagnan, who had been so critical, did a very noble thing. He wrote an editorial saying it was a success, that it had to be acknowledged that it had been a success and we had moved the icy inhabitants of Sweden.

RAFAEL ULLOA: They were really proud. You can say whatever you want, but even when Gabito isn’t part of your family like in my case, he has roots in your family, everybody knows that Gabito is a cool dude. That imagination of his . . . not just anybody has that. Suddenly I believe what the old man there says: that he has two brains . . . So when they gave him the Nobel Prize I wrote an article with the information I had. I sent it to El Espectador. They published it on October 10, 1982, and the next day El Heraldo published it. Someone faxed it to Gabito. And he said to me: “Send me something else.” I like to tell stories about towns. There’s a lady who was a secretary where I work. She knows I’m related to García Márquez and told me: “You inherited that thing from Gabito because those stories are Gabito’s.”

GLORIA TRIANA: That year the Nobel was thirty-one years old, and nothing like our ceremony has happened since, and I’m still tracking it down. There have been African writers, writers from the Caribbean, a Chinese writer, and nothing like the way we did it has happened again.

HÉCTOR ROJAS HERAZO: When he won the Nobel, we were in Spain. The ambassador, who was a novelist too, invited us. The Colombian ambassador invited us in order to greet him. Gabo, who’s smiling a lot, laughed at everything. Then I arrive, very happy, and we gave each other a big hug.

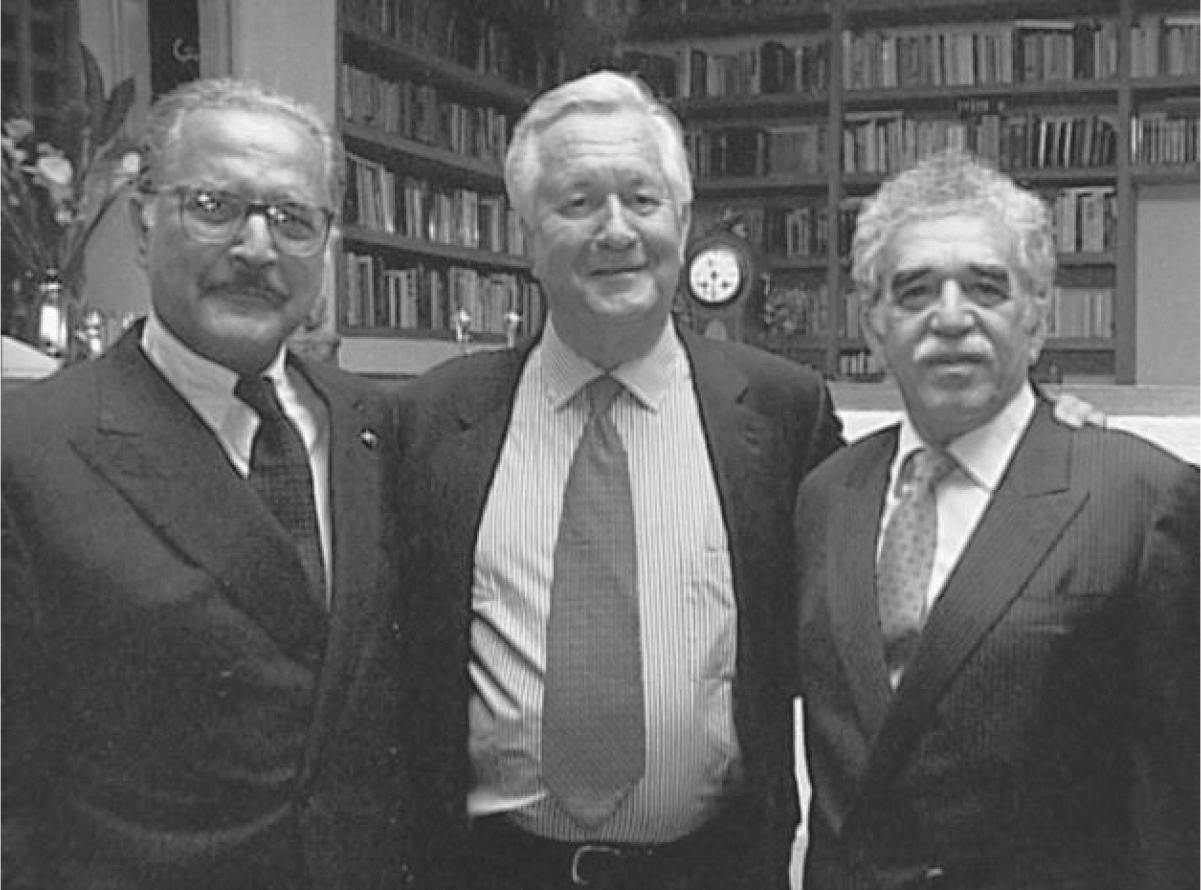

Carlos Fuentes, William Styron, and García Márquez in the US.