ROSE STYRON: He’s a wonderful storyteller and talks about how his grandmother was the great storyteller in his family, and he learned from her. He lived with her when he was a boy. And he said that his mother became a storyteller as she aged but wasn’t one earlier. It was having lived with his grandmother. He also says that knowing how to tell stories is something congenital and hereditary. That is, that it’s natural that many of us think our grandmothers are the ones who told us stories and turned us into the storytellers we are.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: He told me one day: “Do you know what it means to be a good writer?” I said no. “A writer is someone who writes a line and makes the reader want to read the one that follows.” Because Gabo, even in the bad things he has, has that thing of controlling the prose so that you say: “How marvelous! How did he say that?”

ELIGIO “YIYO” GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ: My mother says that Gabito turned out so intelligent because when she was pregnant with Gabito, she took a lot of Scott’s Emulsion. It was the only one of her twelve pregnancies when she took that cod-liver oil. And Gabito came out so intelligent because of the pure cod-liver oil. She says that he was born smelling of Scott’s Emulsion.

RAFAEL ULLOA: I really believe what the old man Gabriel Eligio says. That Gabo is bicephalic. That he has two brains.

ROSE STYRON: I don’t know whether it was true for the rest of the world or not. But the fact is that Macondo was so real for me that it influenced my vision of Latin America. But of course I had another Latin American political experience, I mean, I could see it from the outside, perhaps because of my experience in Argentina, Chile, or Uruguay. The fact that I had been a human rights activist allowed me to see it from the outside, from another perspective, in the same way I saw Central America. So then I wouldn’t say that Macondo turned into all of Latin America for me, but it certainly did for those who had not been in Latin America. But when Bill and I were in Cartagena, during the film festival, to my surprise and delight, I walked along the streets and realized that I already knew them through Gabo’s books . . . even the jars filled with sweets in the market. It’s all so detailed. He had depicted it as a reality. It was a reality. It wasn’t a surprise.

I’m from Baltimore. Not so far south. I mean, southern intensity and lightness are there. I can see that Gabo had read Faulkner. It’s interesting, but for me, Gabo’s town, his city, is much more vivid than the one Faulkner had created.

PATRICIA CASTAÑO: There’s something very interesting that has to be looked at. Do you remember that there’s a story by Gabo when he was writing in El Espectador? He says there, speaking of the magic that surrounds him, that one day he was with a Catalan writer or editor who came to visit him in Cartagena. He recounts everything that happened in those two days, and that the gentleman said to him: “No, well, excuse me, but you don’t even have an imagination. What one experiences in these countries is madness.” Then he narrates everything that happened to that gentleman. But the most impressive thing is that they were having lunch one Sunday in his mother’s house in Cartagena, and suddenly a lady in a Guajiran tunic rang the doorbell. She comes in and says she’s cousin so-and-so and that she came to die. She dreamed she was going to die, and so she came to say goodbye.

ROSE STYRON: When you read Gabo it’s like reading all of Latin America. Or, suddenly you understand it all. Or you think you understand it.

EDMUNDO PAZ SOLDÁN: When you talk about García Márquez, he’s the one who has narrated the continent for us. This is Latin America. And I didn’t feel it was the Latin America where I grew up. My world has been very urban, for better and for worse. So I always saw the world of the tropics from a distance. That wasn’t the Latin America where I grew up.

ILAN STAVANS: Our generation has had to define itself in opposition to García Márquez.

ALBERTO FUGUET: I’ve been in literary workshops and all my classmates, except me, were infected by the García Márquez virus. I mean, it’s not only admiration, but they cling to the story. So I feel that reading García Márquez at a certain age can do you a lot of harm. In other words, I’d prohibit it. As a Latin American. It can affect you very badly and you’re damaged forever.

The other day, in a talk in Lima, Ignacio Padilla wrote a story by García Márquez. I mean, a page. Before coming up onstage, he went to the last seat and wrote for ten minutes, read it aloud, and it was incredible. It was like . . . The captain, his name like Evaristo So-and-so, and it went on and on and on. And you said: “But . . . it was magical realism.” And it totally was. It’s almost like a software you install and it takes off.

ILAN STAVANS: There’s a formula. But also poor García Márquez. It’s not his fault. It’s been pinned on him. Earlier it was Kafka and Sinclair Lewis as magical realists. It comes from Carpentier. I believe García Márquez changed Latin American culture, totally. He changed how Latin America is viewed in the rest of the world. I believe not always beneficially. Like the number of tourists who go to Latin America looking for butterflies, prostitutes. But it isn’t his fault.

ALBERTO FUGUET: I read García Márquez years before I wanted to be a writer. I read him because—and this always annoyed me a little—because it was official reading. And I felt a little more rebellious. It was what we had to read in secondary school. It was literature that was already official, that came from the Ministry of Education. For me it was associated with the establishment. For me, García Márquez was always establishment. Soon afterward he won the Nobel. It was a little adolescent of me, but it was how I felt.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: There’s something very important about Gabo, and it must be said because it’s useful to everybody. Gabo has something that doesn’t exist in Colombia: discipline. Fernando Botero has it, too. Rogelio Salmona has it, the man who designed these buildings. And Gabo has it. There must be more people, but I know only these three. And I can give you in more graphic form what Gabo’s discipline is, which is incredible in a Latin American. Before he was married, I had an unlucky night. I was with two women. It’s the worst thing that can happen to you. You can’t do anything. So then I said: “No, my solution is Gabo. Two men and two women, now that’s another kettle of fish.” I went to Gabo: “Brother, this is my situation.” This is a nice story. He says to me: “I have to correct the third chapter of In Evil Hour.” “And do you have a contract or what?” “I gave myself the assignment that I would correct that third chapter tonight.” There was no way. No way. It would have been the easiest thing in the world to say: “I’ll do it tomorrow. I’ll do it later.” There was no way.

JOSÉ SALGAR: I remember that with Autumn of the Patriarch, Gabo would start to work from five in the morning until not very late because he would always stop writing and start to drink with his friends and talk, but they were very intense and productive working days.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: And he has his life divided with his friends. Work in the morning. In the afternoon he’s with his friends. But in the morning he doesn’t talk to anybody. He’s just working. He’s in his element.

JUANCHO JINETE: When he wrote that thing about Bolívar . . . What’s it called? [The General in His Labyrinth.] So one day Alfonso says to me: “I need to take a trip to Soledad, maestro. I know you have connections in that town.” So then we went there and he said to me: “I have to do this and that and the other. Take me to the city hall, I understand that Simón Bolívar slept there.” I have entrance privileges at the city hall because I helped out when I was manager of the Banco Popular in Soledad. I gave them a few gifts to the guards there. So then they let me go in. Listen to this story. So then I say to him, “Maestro, what do you want to find out?” “You’ll see.” Finally I got to the city hall and I said: “This is Maestro Fuenmayor. Look, I need to know which is the room where Bolívar slept.” So then I swear, the guy says: “Here they say it was this one, this one, this one.” We went up there. “Aha, and what is it that you want, Alfonso?” He says to me: “No, I need to see if when Bolívar would hang his hammock here he could see the square, the square that’s in front of that church there.”

We made two trips like that. Finally I told him: “Well, what is it, what do we come here for?” “No, hombre, it’s just that Gabo’s writing.”

Gabito relied on Alfonso, and Alfonso was the one who corrected all those things for him. What you say is true: in his novels, the things that appear can’t be contradicted. It’s true that Alvaro got down to Soledad and that he looked out from the room so that Gabito could say that Bolívar thought who knows what. Whew! All that was missing was our hanging up his hammock!

JOSÉ SALGAR: He calls and asks me: “Don’t you remember? Where can I get that thing?” So then he gets people to go to the library, to go and get this, and see where that negative is. And he has to have it perfect. Things like the colors, the atmosphere, the music, it has to be exact. If he says: “There was a murmur of Vivaldi,” it was Vivaldi. So my conclusion has always been—and I’ve said this—that it was a human privilege to have successfully beautified journalistic reality, which is so harsh, every day; beautify it with those devices of literature, of music and poetry.

EDUARDO MÁRCELES DACONTE: There’s an example he gives that I think is the best one to illustrate this for us. He says that when he was little, the cook in the house, the maid, once disappeared. Somebody asked: “And what happened to So-and-so?” “Imagine, she was hanging the sheets there outside.” It occurred to someone to say that to mislead him. Do you understand me? “And then . . . uuuhhh . . . she went flying away.” That image was etched in his mind.

RAFAEL ULLOA: Gabo has some marvelous things that leave me surprised. Not long ago he was talking with some friends and we were remembering that thing about the mourners, the old women they hire to cry over the dead. The weepers. And so Pachita Pérez came up, the champion weeper, and he says that old woman was so good at crying that she was capable of synthesizing the entire history of the dead person in a single howl. His words captured the idea of the weeps perfectly. Brilliant. So I like these things.

EDUARDO MÁRCELES DACONTE: That’s true, definitely, García Márquez’s memory is incredible. Because I’ll tell you something: do you remember the stories they told you when you were eight years old? He’s been working on them in his mind for his whole life. This isn’t a question of something coming out just like that . . . It’s an entire process.

JOSÉ SALGAR: Life magazine, when it was still in circulation . . . When Pope John Paul II had just been elected . . . Gabo was in Cuba and they gave him the assignment of going to talk to the Pope so he’d go there to free some prisoners in Cuba. So he couldn’t arrange the visit with the Pope and some very strange tricks were devised. A Polish countess in Rome appeared and called him and said: “Be ready, at any moment I’ll call you to come to Rome, and I’ll arrange your visit with the Pope.” To make a very long story short, the countess calls Gabo at five in the morning when Gabo is in Paris and says: “Come immediately, I have an appointment for you with the Pope at seven in the morning.” And so the man left Paris for Rome and the first thing that occurred to him was to get some decent clothes, a blazer. So he went to a friend who lent him one, but it was too small. Well, the key moment finally came and he arrives there and . . . Brother, let me tell you. The Pope, in white, up there, and the man didn’t know what to do except motion like this with his right hand. The Pope, up there, motions like this and Gabo motioned back. They make a connection, but the Pope didn’t know all the secrets. He came in, and there was a very shiny wooden floor there, and in the middle a table. They both went in. The Pope closed the door and they were alone. Gabo says that at that moment, he thinks: “What would my mother say if she could see me now?” And the story begins and they talk. What’s true is that he managed to raise the question of the men with the Pope, and he left the interview. That night, Mercedes asks him: “Well, how was it?” “The thing with the Pope was perfect. It went very well.” “Nothing strange happened?” “Wait. Since I had to go to something else, I don’t remember, but wait . . . Of course, the button!” “What about the button?” “Wait, because I went in with the blazer I had bought, and we both went in, and at the moment we went in I went up in the air and bam! The button fell off the blazer and went clattering under the table in the middle. Then the only thing I saw was that the Pope went ahead of me, kneeled down, and I saw his slipper. The Pope stood up, took the button, and gave it to me.” And then another few details like, for example, that when they went out, the Pope didn’t know how to open the door or call the Swiss Guards, so the two of them were locked in and couldn’t get out. But at that moment he couldn’t remember all the details. It turned into a very long story because now he remembered all about the countess and everything. So, on the basis of something that passes in the moment, the man turns it into another Hundred Years of Solitude.

ROSE STYRON: His characters are extremely romantic, and even when you end up in an excavation, in a convent, or in something like News of a Kidnapping, there’s still that purely romantic part that remains. In other words, he’s a man who loves people. Who loves life!

JOSÉ SALGAR: I think there aren’t people these days who spend so much money on the telephone, because he doesn’t care how much the phone call costs. Wherever he was, in all those times, he would call. He says so himself. When he had some special thing to tell, he would call Guillermo Cano* or me for any reason. And it was a long conversation. He doesn’t measure the time. But he has a way of paying for the phone. He doesn’t pay the bill, but surely Mercedes must pay it, or that old woman, his agent. So then he says: “Listen, we didn’t realize we were talking for a long time.” From Europe it must be a fortune. He realizes about the time but isn’t happy until he gets to the bottom of the last detail about that button.

ROSE STYRON: I remember that he says it’s his job to be a magician for his readers, but that magicians always begin with reality and return to reality. Though as a novelist he might fly between them and be as magical, as surreal, as he likes, as long as he writes well enough and with enough magic to convince the reader.

SANTIAGO MUTIS: Gabo has a background of alchemical knowledge. And alchemy is what they call magical realism. When the boy goes into the kitchen and says to his mother: “That pot’s going to fall.” The pot’s firmly placed on the table but it slips and breaks when it falls. Colombia has a lot of that, it’s a country where the people believe in that. When you go to a party at a fair or market in Villa de Leyva, the people sprinkle holy water on the bus so it doesn’t drive out of control on the road. That’s how he was. There’s a huge religious background. That is, it’s a religious culture . . . In Gabo it’s the culture. Before that, it was religion.

IMPERIA DACONTE: In Aracataca they say that one night they saw him driving around town in a car with some friends. But he says he hasn’t gone back there.

SANTIAGO MUTIS: I think this happens with Gabo: the country had its oral tradition. I mean, literature didn’t occupy an important place and the oral tradition begins to be pushed back a little. Cities begin to have great importance, things begin to appear that come from a totally different place, and as popular culture begins to rust, to feel threatened, to stop being oral, Gabo takes it in. And it begins to turn into literature.

RAMÓN ILLÁN BACCA: With García Márquez the world has come to know things that everybody knew here. What happened is that they were internationalized. Everybody handled them. The story about the capon . . . that’s something that’s always belonged to us.

RAFAEL ULLOA: What I think is that his greatness is in his imagination. Without that imagination, he would throw a few topics out into the world that would seem unbelievable. But the way he says them . . . Like when he says: “A metal grasshopper leaping from town to town along the banks of the Magdalena,” to describe those anvils. And he calls them metal grasshoppers. That is, things that connect technical things and crickets. The simpler the better.

RAMÓN ILLÁN BACCA: In the story about the curlews, García Márquez puts in Terry and the Pirates and everybody says: “Look, that’s an invention of García Márquez.” No, it isn’t. That’s a lie. Terry and the Pirates was the comic strip that came out in the Sunday papers. The first Sunday papers in color were printed in Barranquilla, in 1929, and they were the Sunday papers that practically everybody bought on Saturday for five cents. I remember that I bought them. There was Little Orphan Annie. Winnie Winkle. Tarzan. He puts Terry and the Pirates into a story.

JOSÉ SALGAR: The story of the Beautiful Remedios* in One Hundred Years of Solitude: an image, a symbol he gave to an ordinary girl which must have been like what happened with the Virgin Mary at first. He made her sublime through literature. It’s not exactly the Beautiful Remedios ascending to heaven, but it’s an image he created that, in the concept of the characters in the novel, had that meaning. It’s a way of beautifying the story. Of telling the story well when the facts fall short. Same thing in Love in the Time of Cholera . . . He knew the characters directly. Basically, it’s the story of Gabo’s father and mother, but it’s the story he heard from his grandfather. And he begins to remember and to assimilate, and then he starts to put it together. Things his grandfather never thought about again or anything, but he reconstructs it, like the Pope’s button. So then, the real genius of the man lies in having a prodigious memory and in confirming the facts responsibly so he won’t stray too far from reality. And in the beauty of his language. Because the man has mastery. First he devoted himself to the classics in order to write well. And to realism. And to poetry. And to music. Gabo is also fanatical about music. So with music and poetry in his head, a nice story comes to him and he knows how to tell it. And he tells the story without straying too far because there’s also his journalistic responsibility. You can’t start creating fantasies. You have to say exactly what’s there.

ROSE STYRON: It’s fantastic, because having begun as a reporter, I think he always takes that into account. He sees journalism as a literary genre. Just like fiction. The way he writes, everything seems like a news item, even when people go flying away.

RAMÓN ILLÁN BACCA: Magical realism makes up only half of his work. Perhaps scholars study that aspect of magical realism in García Márquez a great deal. The only thing I can tell you about magical realism is that here on the coast, one hears so many things that really are magical realism and that grow very well around here. For example, I’m going to tell you the story of Professor Darío Hernández, in Santa Marta. I tell it in Deborah Kruel and I’ve told it to everybody. Professor Darío Hernández was in Brussels, as is proper for all decent people from Santa Marta. He wasn’t very rich, but there he was, in Brussels. He studied piano. He played for Queen Astrid. He comes back because in ’31, ’32, I don’t really know how, in what year, there’s agitation because of the stock market crash in New York, that whole story. So then a lot of people had to come running back because banana shipments fell, all those things that made up the Great Depression. So then Darío came, he returns to Santa Marta. Naturally, in the recently opened Santa Marta Club, they say: “Play something, Darío.” So then he comes and plays Moonlight Sonata by Beethoven. “Aha, Darío, play something else.” Chopin’s Polonaise. Liszt’s Liebestraum. “Listen, is that what you went there to learn? You don’t know how to play the cumbia Puya Puyarás, for example?” Then Darío, indignant, slammed down the piano lid and said: “This town is never going to see me play a single note again.” Darío lived to the age of ninety. When this happened, he was thirty. So then he lived sixty more years. He was conductor of the municipal band. Then he was the director of Fine Arts, and pianists like Carol Bermúdez and Andrés Lineros came out of there, and they’re very popular pianists. And nobody ever heard him play another note. And those who passed his house, which was an old house where he lived with two mummified aunts, older than he was, said he had put cotton between the piano strings; that is, people heard nothing but a clap clap clan clan when he practiced every morning. If that isn’t a story of magical realism, I don’t know what is. And it was Darío, and we saw him every day.

MARGARITA DE LA VEGA: I used to give paperback editions of One Hundred Years of Solitude with an awful cover as gifts. Later on it was the naked couple in the flowers. It was also very gaudy. I bought five or six copies, and when I was invited to dinner, instead of bringing a bottle of wine, some cookies, whatever, I would bring One Hundred Years of Solitude. I remember that one lady I had given it to called and invited me to lunch. She presented it to me with fifteen annotated pages, such and such a page, such and such a line, detailing all the things in One Hundred Years of Solitude that couldn’t exist for scientific reasons, like the duration of the rains. And the first Aureliano, the one who founds Macondo with Úrsula, lives a very long time. And besides that, he survives tied to a papaya tree in the courtyard. But I knew people who tied up idiots in the courtyard.

And the fact is that the word “marvelous” and the word “magical” are not the same. Carpentier talks about marvelous realism with a very clear explanation, because Carpentier, who is a great writer and does that kind of thing, is also a theoretician. He had studied. He was an ethnomusicologist. And he, one of his things, is that marvelous realism is produced because in Latin America— to use the term that’s, well, popular today—what happens is that not only several climates, several civilizations, but also several periods all meet at the same time, in the same situation, and in the same era. So that feudalism is right beside modernism.

The airplane is beside the burro. There’s the chain saw and the Uzi machine gun and arrows, too. All at the same time. So then, there’s this interweaving that many people, especially Cuban theoreticians like Fernando Ortiz, have worked on: he does so in his book Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar, where he explains transculturation, a term he coined that comes about when you mix the three cultures: the indigenous, the Spanish, and the African. And just like this lady made me the list of what didn’t work, I remember that I sat down and said: “I should have told her point by point everything that is true, but then how boring. The magic is reading it and entering that world and not questioning this side or the other.”

RAMÓN ILLÁN BACCA: Generally on Tuesday I would go to have lunch with Germán [Vargas]—some coffee, some cheese, whatever—and we’d talk a long time about literature. But whenever Gabo came to Colombia, Germán became nervous that day. One day he said to me: “You can’t come for lunch today because today I’m going to eat with Guillo Marín.” On that day he was more nervous than ever. His wife Susy was nervous. Tita Cepeda arrived in her big car and sounded her horn—in their agreed way. Paparapapá! I already knew that Guillo Marín was Gabo, and I disappeared. Well, so then something like nine years went by. Then he says to me once: “But, haven’t you met Gabriel García Márquez?” I tell him: “But you’ve introduced him to every gringo professor who’s passed through here and you haven’t wanted to introduce him to me.” So then he says: “No, now when we go to Cartagena I have to introduce you to him. The two of you would get along.”

And then Germán and I happen to be in Cartagena at the same time, because I was at the premiere of My Macondo, a film some Englishmen made, and García Márquez appeared in it. And I had a small speaking part. And so on and so forth. So then I was with Guillermo Henríquez, who hates García Márquez now, and Julio Roca. We were there when the Englishmen say to us: “Well, then, let’s go to the birthday party, it’s a vallenato party.” So then, for the whole day, all the papers in Cartagena had been dedicated to saying let’s hope there are no party crashers, no party crashers accepted, and I don’t know what about party crashers. Then Guillermo says: “No, Ramón and I aren’t going. We don’t like vallenato parties.” And then, not to be left behind, I said: “We don’t like vallenato parties.” And when I go back Germán says to me: “Faggot, why didn’t you go? It would have been perfect. Well, some other time.” And wham! Germán died. I couldn’t meet him.

MIGUEL FALQUEZ-CERTAIN: He’s already met him, but the time he was put on display was when Tita Cepeda gave a party in her house when García Márquez returned to Barranquilla. That was in the eighties, and so she had a party with a waiter and everything. And when Ramón came to the door, the porter stopped him and said he couldn’t go up. “But what do you mean? I’ve been invited.” “No, sir.” He got sick that day. Oof! He almost cried. He left with his tail between his legs. I imagine that it was very exclusive to have García Márquez in your party then because he had just returned to Colombia. It was like: only intimate, intimate, intimate friends. So from that time on it was a joke: “Poor me, I’m the only person left in Barranquilla who doesn’t know García Márquez.” Every lizard, everybody gave a party and invited him. He was the only one left to meet him.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: Look, I can tell you my part and it’s tremendously disheartening. I haven’t found anything based on me in all of Gabo’s work, except for one thing he said in an article. It turns out I had a friend who was building a water tank in Aracataca. He told me: “The heat was so bad we had to work at night and pick up the metal sheets wearing gloves because they were still too hot to touch.” [Gabo] recounted that in an article.

EDUARDO MÁRCELES DACONTE: Once there was a writers’ conference in Sincelejo. I’m talking about ’84, ’85, somewhere in there. And García Márquez was living in Cartagena at that time, and I was in Barranquilla, and I was going to Sincelejo. And when I passed through Cartagena, I stopped and called him on the phone. I say: “Gabo, I’m here.” He says: “Come for lunch.” Okay, so I go for lunch. At that time he usually stayed in his sister’s house, in Bocagrande, because he had barely settled in. And I went to have lunch with him and he says: “Eduardo, what’s the news? What’s happening in Aracataca?” And I say: “Well, no, about Aracataca no, but what I can tell you is that my uncle Galileo Daconte . . .” My uncle Galileo Daconte had just died. “Ay, damn it!” And he was his best friend in my family; when they were little he and that uncle of mine had been the same age. And then he dies. I ask him what he was writing and he tells me a little of what he was writing, which was Love in the Time of Cholera. So then, what happens? When I’m reading Love sometime afterward . . . One of the characters is named Galileo Daconte. He’s, what do you call it? The coachman of that character, the doctor who falls and kills himself. The coachman’s name is Galileo Daconte. So then I imagine that since he was writing that part at the time I visited him . . . and since I told him he had died, bam! He put him in. And even more in The Trail of Your Blood in the Snow, where the character is named Nena Daconte, who’s my mother’s sister who was always called the Nena, Nena Daconte.

When we told her: “Look, aunt, Gabo . . .” and she: “Ah yes, that Gabito . . . Look. That Gabito has a memory . . .” No. She really doesn’t resemble the character. She’s simply the name and idea of what she could be.

MARGARITA DE LA VEGA: He writes Love between ’82 and ’85. García Márquez presents a person from the old families of Cartagena who leaves the country to study and returns. Gabo takes the experience of my father, who left Cartagena to study in Paris and returned, and how he survived. He’s Juvenal Urbino. Now, the love story has nothing to do with my father. It’s the part about being a person from Cartagena from a traditional family, insofar as the families of Cartagena were traditional, because when I look at the families of my friends and others, there was always a little bit of everything. When I saw him, I said: “No, but that character from Love in the Time of Cholera isn’t my father.” Then he said to me: “No, Florentino is my father. We won’t take that away from him.” Then he said to me: “I was interested in somehow transforming the love story of my father and mother.” And I think that’s the time when his father’s sick. Florentino Ariza is his father and the lady he places as the doctor’s wife is his mother, Fermina Daza. Juvenal, my father, marries Fermina, his mother. My mother doesn’t go out for the afternoon promenade. He transformed all that with the love story and that comes from nineteenth-century stories. That’s why I say that I see my father’s influence more in the style of the novel, which is a nineteenth-century novel with lots of characters, written in the style of Balzac. It has a huge number of characters. It’s the portrait of an age. The love story is important, but it isn’t fundamental. It was his source of inspiration. He always wanted to write something new and different.

My father didn’t die like Dr. Urbino because of a parrot, but he absolutely would have risked his life for an animal, because people gave him parrots and parakeets and whatever as presents. We had a macaw that wandered through the house and was named Gonzalo; he danced and everything.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: Somewhere his literary agent tells me that the photograph in Innocent Eréndira is of me, but no . . . I mean, the only thing is that I’m a photographer and he was a photographer, but there’s nothing I said, or told him, no. So the elaboration has to exist, but it’s so complex that, as I’ve said, you can’t follow it.

CARMELO MARTÍNEZ: I appear as Cristo, a friend of Cayetano’s, but Gabito doesn’t describe him in the novel, he leaves some doubt. He could have been me or a cousin of Cayetano’s who died of brain cancer.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: You have to be very careful when you think: “I inspired the work.” You have to discount all that because I think his great inspiration was his grandmother and his mother and his family. I remember the things he would tell me, that the family talked about, that are written by Gabo. Of course, Gabo is telling them to you. About how a female relative of his was combing her hair and the grandmother said: “Don’t comb your hair at night because ships get lost when you do . . .” The colonel’s in his family. It’s an entire family fortune that he accumulates and keeps spending for his whole life.

I haven’t found anything directly having to do with his friends, and I think I know them very well, all of them very well. He’s stolen ideas from them, but openly. I mean, Mutis began to write The General in His Labyrinth. He took one thing and then he said: “No, you’re not going to do anything with that. I’m going to steal it from you.” But that’s all. I mean, it’s circumstantial because the other man also talks about Bolívar when he’s going to die, is going toward death, but you can read both things, the two things coexist, and you can’t say: “Look, Gabo, you copied this.” The elaboration is so complex that it’s no longer an elaboration.

RAFAEL ULLOA: That guy he presents there, that Gypsy who arrives and changes, that guy resembles his father, who did all those things. Or that other madman he presents in the story about Blacamán. I’m telling you it was Jorgito, from there in Sincé, who would have a snake bite him. And there’s one in “Blacamán, Seller of Miracles,” who has something of Jorgito. Because Jorgito, as I say, would smear himself with pomade . . . “And now you’ll see that a fer-delance . . .” Of course, the serpent’s fangs had been removed.

JOSÉ SALGAR: One Hundred Years isn’t a newspaper story but it has a newspaper background, which is the tragedy of La Guajira, which is the life of coastal people, which is the imagination of the people, because all the characters are real. Because the Gypsy sold things there. Úrsula. All the characters have a real background that makes them newspaper characters. And it ends with the tragedy of the banana plantations, and basically, many of the characters of One Hundred Years must have died on the banana plantations. Then too, he puts in many people from La Cueva and uses their real names. He gathers together. It’s a kind of compilation of the most beautiful memories of his youth.

EMMANUEL CARBALLO: I thought it was something . . . I knew it was how they talked in Barranquilla, but he had invented a way of putting words together and making a style different from the different styles at that time. And he brought in a new fashion with that language. And not only that language: that ability to imagine! A power of creation. For me it was invention. For me there was no Colombian word or Mexican word; there were words that sounded good and said important things.

ROSE STYRON: I think he’s a man of great, great profundity, that he’s a creative man. I’ve heard him say that to explain the mystery of creation, he would do anything. And so he sits down to talk with a film student or whoever. He says you never get to the heart of the mystery of creation, but that he’s always ready to rummage around and go deeper into it.

JOSÉ SALGAR: He’s a tape recorder, but a magnificent one. Everything stays with the man. A subject emerges and he turns it around. He has a certain cadence, a very pleasant something for telling stories. He’s listening and suddenly he asks you a question. There’s always an exchange. He goes back to the central facts in the life of the person who is his interlocutor, I believe. He asks you: “Aha, do you remember Sánchez?” (A photographer.) “Where did he come from? Who gave him the name Dog? Why is he the Dog?” And he begins to find out about his life. I don’t know if he does it unconsciously, but he’s creating the novel of the el Perro Sánchez. He’s a tremendous presence.

SANTIAGO MUTIS: The Gabo of today is a Gabo who works things out. He tells his story. Which is literary. It doesn’t mean it isn’t true. It’s literary.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: He’s a character in search of an author. And he found him.

GERALD MARTIN: The first time I saw him was in Havana in the year 1990. In his house in Havana. I felt I had lived for that moment. It was out of this world how well we got along. We talked for four straight hours. When he wants to be, he’s marvelous. A delicious conversationalist. At the end of the day he said: “And what time will you be here tomorrow?” Imagine! I left there flying with happiness. The next day I returned and found a different person. When I sat down he said: “Do you know something? I couldn’t sleep last night, I was traveling through the labyrinth of Latin American literature.” I realized right away, and was very frightened, that he was talking about my book Journeys Through the Labyrinth that had been published the year before, and that some friend (in English we’d say, ironically, a well-wisher) must have lent it to him; in it I criticize Autumn of the Patriarch. “I’m the patriarch,” he said to me. “It’s my self-portrait. If you don’t understand that and if you don’t like the patriarch, how will you be my biographer?” Gabo had realized that night that it’s difficult to be friends with your biographer, but even so we continued to get along well, but we were no longer soul brothers. We never again had the relationship we’d had at that first meeting; but we never forgot it either, it was always there.

SANTIAGO MUTIS: Yes, Gabo has had really lovely people. Generous and beautiful, and that’s why Gabo is a person filled with gratitude. Because he has people to be grateful to. And being grateful isn’t anything different from being humane, but a torrent of humaneness. And Gabo, I believe, is humane. And his books are humane.

CARMEN BALCELLS: When he brought me a copy of the manuscript for Of Love and Other Demons in the year ’94, it was a little difficult for me to understand that he had dedicated the book to me. And the dedication said: “To Carmen bathed in tears.” That dedication was the one he had put in my copy of Autumn of the Patriarch because of the story of the publication of that book, which was a disaster. He put that dedication in the presentation copy of the first edition, which was falling apart. When I saw that text I didn’t understand completely, or with the speed that would have been necessary, that he was dedicating the book to me. To Carmen Balcells. And it was so special a moment that today I still remember physically the details of his presence, of the manuscript, of everything just as it happened, and the truth is I don’t know whether I was capable of expressing or translating the emotion I felt. I don’t think so. And I didn’t. I didn’t express it well.

GUSTAVO GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ: I said at the start that Gabito and I have a rivalry as to who has the better memory. For example, he doesn’t remember when, in Cartagena, around 1951, a representative of Losada Publishers came looking for writers and he asked Gabito if he had a novel. So then Gabito said to me: “Listen, help me out here,” and he took out the originals of Leaf Storm to read them. We were in the middle of reading them when Gabito stopped and said: “This is good, but I’m going to write something that people will read more than the Quijote.”

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: Here in this photograph I’m with Gabriel and Diego. He’s my son. In Gabo’s house. A very amusing day. He was writing and he had us come in; something very unusual for him. I don’t know which novel he was writing at that moment. He says to me: “I’ve written the whole book on this thing, this machine.” It was a computer. And he says: “But, just in case, look.” He opens a drawer and he had it all typed out.

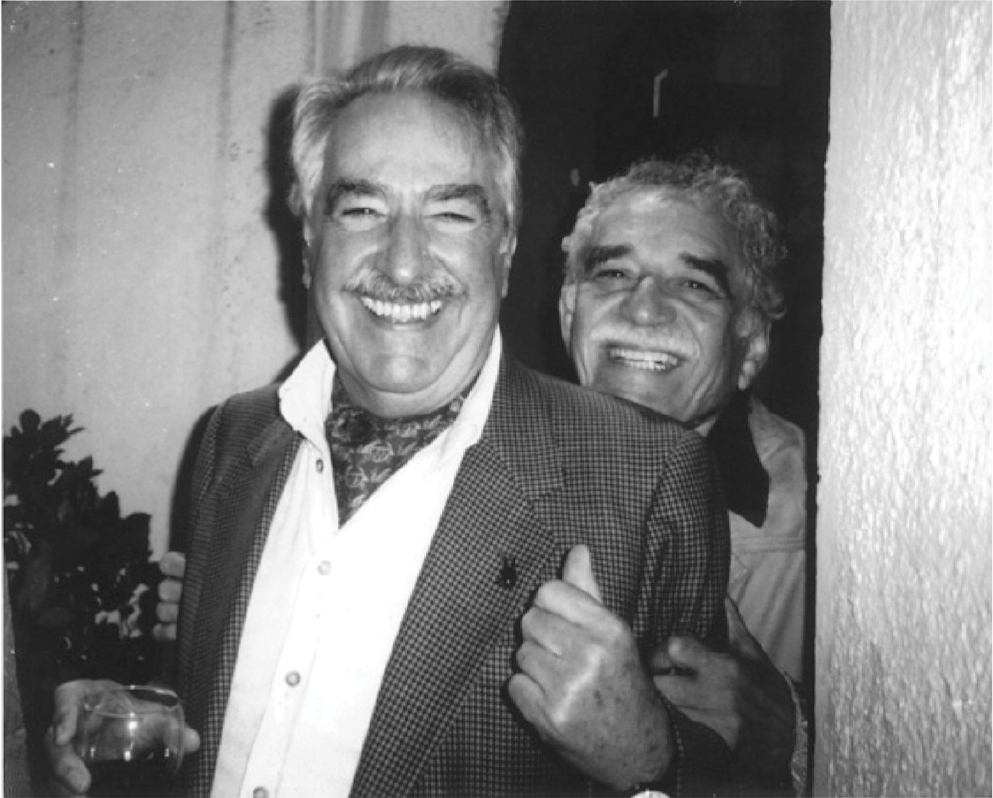

Álvaro Mutis and García Márquez.

* Guillermo Cano, son of Fidel Cano Gutiérrez, founder of El Espectador. When García Márquez started working there as a reporter, he was twenty-seven at the most and the paper’s editor. When Guillermo Cano was murdered in 1986 by two hit men linked to drug cartels in reprisal for denouncing the ties between traffickers and politicians, García Márquez wrote a heartfelt and hyperbolic column describing how young Cano had a visceral sense of what made news. He recalls the time Cano made them cover a three-hour-long rainfall; his insistence that he interview the sailor that ended up giving García Márquez his first scoop and is now News of a Shipwreck, part of the canon. It was under Cano that the paper started doing film reviews, many written by García Márquez, who was then seriously considering becoming a filmmaker.

** Beautiful Remedios, or Remedios la bella, is one of the most iconic characters of One Hundred Years of Solitude. The innocent girl-woman, unaware that she is the most beautiful woman in the world, leaves behind a trail of men who die after trying to seduce her. Remedio’s story of ascension to the heavens while laying out bedsheets to be dried is one of the most studied cases of García Márquez magical realism. He claims that image has been in his head because that’s how the women around him explained the disappearance of a young woman who eloped.