Bangkok’s history as a town began in the 16th century when a short canal was dug across a loop of the Chao Phraya river to cut the distance between the sea and the Siamese capital at Ayutthaya. Over the years, monsoon floods scoured the banks of the canal until it widened to become the main course of the river. On its banks rose two towns – originally trading posts along the river route to Ayutthaya, 85km (55 miles) north – Thonburi on the west and, on the east, Bangkok. At the time, Bangkok was little more than a village (bang) in an orchard of wild plum trees (kok). Hence, the town’s name, Bangkok, which translates as “village of the wild plum”.

Mural of the Grand Palace in Bangkok.

Marcus Wilson Smith/Apa Publications

The Longest Place Name Ever

In 1782, King Rama I decided the name Bangkok was insufficiently noble for a royal city so he renamed it Krungthep mahanakhon amonrattanakosin mahintra ayutthaya mahadilok popnopparat ratchathani burirom udomratchaniwet mahasathan amonpiman avatansathit sakkathattiya visnukamprasit. In English this means: “Great City of Angels, City of Immortals, Magnificent Jewelled City of the God Indra, Seat of the King of Ayutthaya, City of Gleaming Temples, City of the King’s Most Excellent Palace and Dominions, Home of Vishnu and All the Gods”. Most Thais, however, refer to Bangkok by just two syllables, Krung Thep, or “City of Angels”, in everyday speech.

Ayutthaya prospered as the capital of Siam (the name of old Thailand) for more than four centuries, but in 1767 it was captured by the Burmese after a 14-month siege. The Burmese killed, looted and set fire to the whole city, plundering Ayutthaya’s many rich temples and melting down all the gold from images of the Buddha. Members of the royal family, along with some 90,000 captives and the accumulated booty, were removed to Burma.

European impression of 17th-century Ayutthaya.

Luca Invernizzi Tettoni

Despite their overwhelming victory, the Burmese didn’t retain control of Siam for long. A young general named Phya Taksin gathered a small band of followers during the final Burmese siege of the Thai capital. He and his comrades broke through the Burmese encirclement and escaped to the southeast coast. There, Taksin assembled an army and a navy. Only seven months after the fall of Ayutthaya, Taksin’s forces returned to the capital and expelled the Burmese occupiers.

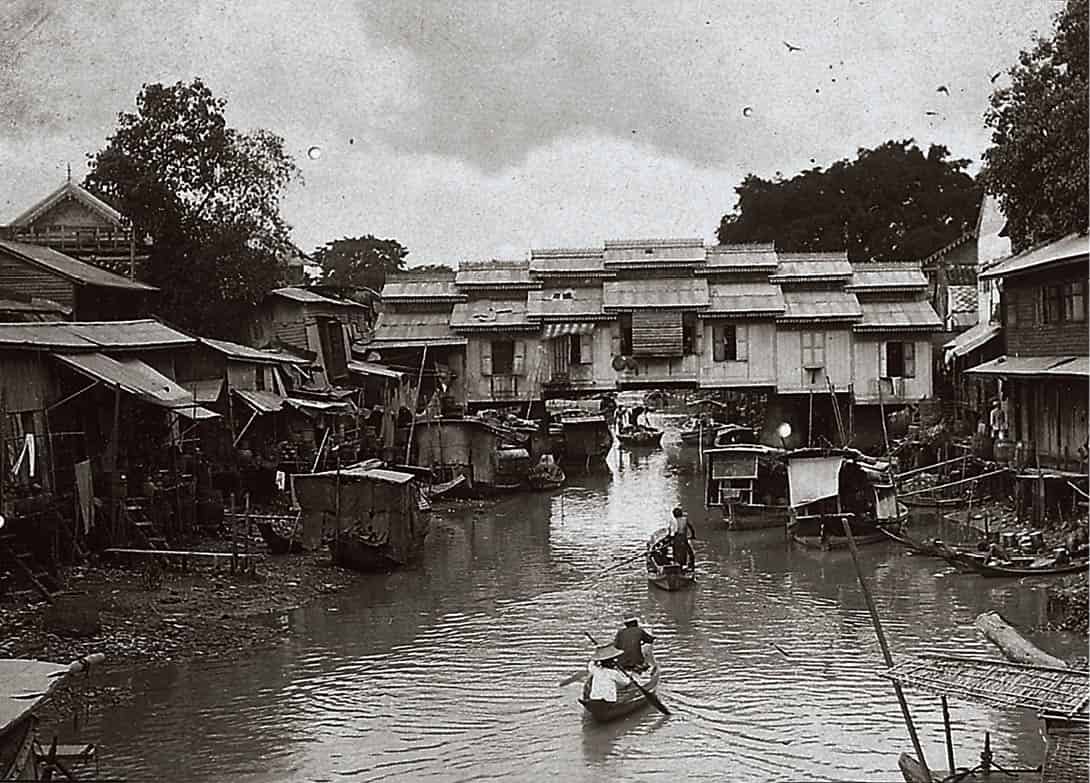

Bangkok canal in the late 19th century.

Public domain

Move to Thonburi

Taksin had barely spent a night at Ayutthaya when he decided to transfer the site of his capital to Thonburi. Here he ruled until 1782. In the last years of his reign, he relied heavily on two trusted generals, the brothers Chao Phya Chakri and Chao Phya Surasi, who were given absolute command in their military campaigns. Meanwhile at Thonburi, Taksin’s personality underwent a slow metamorphosis, from strong and just to cruel and unpredictable. When a revolt broke out in 1782, Taksin abdicated and entered a monastery, but was executed shortly thereafter.

Early map of Bangkok’s waterways.

Public domain

Start of the Chakri dynasty

The official who engineered the revolt offered the throne to Chao Phya Chakri on his return from Cambodia. General Chakri assumed the kingship on 6 April – a date still commemorated as Chakri Day – thereby establishing the still reigning Chakri dynasty. On assuming the throne, Chakri took the name of Ramathibodi. Later known as Rama I, he ruled from 1782 until 1809. His first action as king was to transfer his capital from Thonburi to Bangkok.

After his abdication Taksin was executed in the traditional royal manner – with a blow to the neck by a sandalwood club concealed within a velvet bag.

French Jesuit ambassadors arriving in the Kingdom of Siam in the 17th century.

CCI/REX/Shutterstock

Rama I was an ambitious man eager to re-establish the Thai kingdom as a dominant civilisation. He ordered the digging of a canal across a neck of land on the Bangkok side, creating an island and an inner city. Rama I envisioned this artificial island as the core of his new capital. Within its rim, he would concentrate the principal components of the Thai nation: religion, monarchy and administration. To underscore his recognition of the power of the country’s principal Buddha image, he called this island Rattanakosin) or the “Resting Place of the Emerald Buddha”.

Artist’s impression of King Mongkut (Rama IV).

Getty Images

To dedicate the area solely to statecraft and religion, he formally requested that the Chinese living there move to an area to the southeast. This new district, Sampeng, soon sprouted thriving shops and busy streets, becoming the commercial heart of the city in what is now known as Chinatown.

Rama I then turned his attention to constructing the royal island’s principal buildings. First was a home for the Emerald Buddha, the most sacred image in the realm, which, until then, had been resting in a temple in Thonburi. Two years later, in 1784, Wat Phra Kaew was completed. A palace was next on his agenda; the Grand Palace was more than a home, it contained buildings for receiving royal visitors and debating matters of state. The last building to be constructed, the Chakri Maha Prasat, was not erected until late in the 19th century. Until 1946, the Grand Palace was home to Thailand’s kings. The palace grounds also contain Wat Pho, the National Museum, prestigious Thammasat University, the National Theatre, and various government offices.

King Mongkut (Rama IV) and his wife.

Corbis

Rama II and Rama III

Rama I’s successors, Rama II and Rama III, completed both the consolidation of the Siamese kingdom and the revival of Ayutthaya’s arts and culture. If Rama I laid the foundations of Bangkok, it was Rama II who instilled it with the spirit of the past. Best remembered as an artist, Rama II (ruled 1809–24), the second ruler of the Chakri dynasty, was responsible for building numerous Bangkok temples and repairing others, most famously Wat Arun, the Temple of Dawn, which was later enlarged to its present height by Rama IV. He is also said to have carved the great doors of Wat Suthat, throwing away the chisels so his work could never be replicated.

Rama II reopened relations with the West, which had been suspended since the time of former King Narai, and allowed the Portuguese to open the first Western embassy in Bangkok.

Rama III (ruled 1824–51) continued to open Siam’s doors to foreigners. A pious Buddhist, Rama III was considered to be “austere and reactionary” by some Europeans. But he encouraged American missionaries to introduce Western medicine, such as smallpox vaccinations, to Siam.

Chulalongkorn (Rama V) poses with the Crown Prince and other young students.

Corbis

Mongkut (Rama IV)

With the help of Hollywood, Rama IV (ruled 1851–68) became the most famous king of Siam. More commonly known as King Mongkut, he was portrayed by Yul Brynner in The King and I as a frivolous, bald-headed despot – but nothing could have been further from the truth. He was the first Thai king to understand Western culture and technology, and his reign has been described as the bridge spanning the new and the old.

Bangkok’s Pig Shrine

Close by Wat Ratchabophit in downtown Bangkok is an unusual shrine in the likeness of a golden pig. It is dedicated to the chief consort of King Chulalongkorn, Queen Saowapha (1864–1919), who was born in the Chinese zodiacal Year of the Pig. The “pig shrine” is also an early monument to the women’s movement in Thailand. In 1897, Queen Saowapha founded a college of midwifery in Bangkok. She also founded the Thai Red Cross Society, and built schools for girls in Bangkok and in the provinces. Her court was recognised as a centre for fine arts; young girls attached to the Siamese court attained the equivalent of a university education.

The younger brother of Rama III, King Mongkut spent 27 years as a Buddhist monk prior to his accession to the throne. This gave him a unique opportunity to roam as a commoner among the populace. He learned to read Buddhist scriptures in the Pali language; missionaries taught him Latin and English. As a monk, Mongkut delved into many subjects: history, geography and the sciences, but he had a particular passion for astronomy. Mongkut instituted a policy of modernisation, and England was the first European country to benefit from this, when an 1855 treaty granted extraterritorial privileges, a duty of only 3 percent on imports, and permission to import Indian opium duty-free. Other Western nations followed suit with similar treaties. When Mongkut lifted the state monopoly on rice, it rapidly became Siam’s leading export.

Chulalongkorn with his son Vajiravudh

Getty Images

King Chulalongkorn, who was just 15 when he ascended the throne, went on to abolish slavery and completely modernise Thailand’s institutions, improving both education and health care.

In 1863, Mongkut built Bangkok’s first paved road – Thanon Charoen Krung (Prosperous City) or, as it was known to foreigners, New Road. This 6km (4-mile) -long street, running from the Grand Palace southeast along the river, was lined with shops and houses. He also introduced new technology to encourage commerce. The foreign community moved into the areas opened by the construction of New Road. They built their homes in the area where the Mandarin Oriental Hotel now stands, and along Thanon Silom and Thanon Sathorn, both rural retreats at the time.

Procession of royal barges along the Chao Phraya River at Prajadhipok’s (Rama VII) 1925 coronation.

M.C. Piya Rangsit

Chulalongkorn (Rama V)

Mongkut’s son, Chulalongkorn (Rama V), was only 15 when he ascended the throne in 1868. The farsighted king immediately revolutionised his court by ending the ancient custom of prostration, and by allowing officials to sit on chairs during royal audiences. Chulalongkorn’s reign was truly revolutionary. When he assumed power, Siam had an under-equipped military force, few roads, and no schools, railways or hospitals. He brought in foreign advisors and sent his sons and other young men to be educated abroad. He also founded a palace school for children of the aristocracy, following this with other schools and vocational centres. During his reign, Chulalongkorn abolished the last vestiges of slavery and, in 1884, introduced electric lighting. He hired Danish engineers to build an electric tram system 10 years before the one in Copenhagen was completed, and encouraged the import of automobiles about the same time they began appearing on American streets.

Chulalongkorn changed the face of Bangkok. By 1900, the city was growing rapidly eastward. In the Dusit area, he built a palace, the Vimanmek Mansion and constructed roads to link it with the Grand Palace. Other noble families followed, building elegant mansions. In the same area, he constructed Wat Benjamabophit, the last major Buddhist temple built in Bangkok.

In the area of foreign relations, however, Chulalongkorn had to compromise and give up parts of his kingdom in order to protect Siam from foreign colonisation. When France conquered Annam in 1883 and Britain annexed Upper Burma in 1886, Siam found itself sandwiched between two rival expansionist powers. Siam was forced to surrender to France its claims to Laos and western Cambodia. Similarly, certain Malay Peninsula territories were ceded to Britain in exchange for renunciation of British extraterritorial rights in Siam. By the end of Chulalongkorn’s reign, Siam had given up sizeable tracts of fringe territory. But that was a small price for maintaining the country’s peace and independence. Unlike its neighbours, Siam has never been under colonial rule.

1947 coronation of King Bhumibol Adulyadej.

Public domain

Vajiravudh (Rama VI)

King Chulalongkorn’s successor, his son Vajiravudh, started his reign (1910–25) with a lavish coronation. He was educated at Oxford and was thoroughly anglicised, and his Western-inspired reforms aimed at modernising Siam had a profound effect on modern Thai society.

One of the first changes that Vajiravudh instituted was a 1913 edict which demanded that his subjects adopt surnames. In the absence of a clan or caste system, genealogy was virtually unheard of in Siam at that time. Previously, Thais had used first names, a practice that the king considered uncivilised. The law generated much initial bewilderment, especially in rural areas, and Vajiravudh personally coined patronymics for hundreds of families. To simplify his forebears’ lengthy titles, he invented the Chakri dynastic name, Rama, to be followed by the proper reign number. He started with himself, as Rama VI.

From Siam to Thailand

The man partly responsible for the end of Thailand’s centuries-old absolute monarchy, Luang Phibulsongkhram, or Pibul, tried to instil a sense of mass nationalism in the Thais when he was elected PM in 1938. With tight control over the media and a creative propaganda department, Pibul whipped up sentiment against the Chinese. Chinese immigration was restricted, Chinese workers were barred from certain jobs, and state enterprises were set up to compete in Chinese-dominated industries. By changing the country’s name from Siam to Thailand in 1939, Pibul intended to emphasise that it belonged to Thai ethnic groups and not to the Chinese.

To bring Thai ideals of femininity into line with Western fashions, women were encouraged to grow their hair long instead of having it close-cropped, and to replace their dhoti, or wide-legged Thai trousers, with the panung, a Thai-style sarong. Primary education was made compulsory throughout the kingdom; Chulalongkorn University, the first in Siam, was founded, and schools for both sexes flourished during Vajiravudh’s reign.

Vajiravudh (Rama VI).

Public domain

Vajiravudh preferred individual ministerial consultations to summoning his appointed cabinet. His regime was therefore criticised as autocratic and lacking in coordination. His extravagance soon emptied the funds built up by Chulalongkorn; near the end of Vajiravudh’s reign, the national treasury had to meet the deficits caused by his personal expenses.

The king married late. His only daughter was born one day before he died in 1925. He was succeeded by his youngest brother, Prajadhipok, who inherited the problems created by the brilliant but controversial former ruler.

Thai school children in the late 1940s.

Corbis

Prajadhipok (Rama VII)

Prajadhipok’s prudent economic policies, combined with the increased revenue from foreign trade, amply paid off for the kingdom. In the early years of his reign, communications were improved by the advent of a wireless service, and Don Muang Airport began to operate as an international air centre. It was also during the course of his reign that Siam saw the establishment of the Fine Arts Department, the National Library and the National Museum, institutions that continue today as important preservers of Thai culture.

The worldwide economic crisis of 1931 affected Siam’s rice export and the government was forced to cut the salaries of junior personnel, and retrench officers in the armed services. Discontent brewed among army officials and bureaucrats. In 1932, a coup d’état ended absolute rule by Thai monarchs. The coup was staged by the People’s Party, a military and civilian group masterminded by foreign-educated Thais. The chief ideologist was Pridi Banomyong, a young lawyer trained in France, who is now often cited as “The Father of Thai Democracy”. On the military side, Capt. Luang Phibulsongkhram (Pibul) was responsible for gaining the support of important army colonels.

With only a few tanks, the 70 conspirators sparked off the “revolution” by occupying strategic areas and holding the senior princes hostage. Other army officers stood by as the public watched. At the time, Prajadhipok was in Hua Hin, a royal retreat to the south. Perceiving he had little choice and to avoid bloodshed, he agreed to accept a provisional constitution by which he continued to reign.

The power of Pibul and the army was further strengthened in October 1933 by the decisive defeat of a rebellion led by Prince Boworadet, who had been the war minister under King Prajadhipok. The king had no part in the rebellion, but had become increasingly dismayed by quarrels within the new government. He moved to England in 1934 and abdicated in 1935. Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII), a 10-year-old half-nephew, agreed to take the throne, but remained in Switzerland to complete his schooling.

After a series of crises and an election in 1938, Pibul became prime minister. His rule, however, grew more authoritarian. While some Thai officers favoured the model of the Japanese military regime, Pibul admired – and sought to emulate – Hitler and Mussolini. Borrowing many ideas from European fascism, he attempted to instil a sense of mass nationalism in the Thais (see box).

King Prajadhipok in 1926.

Corbis

Post World War II

On 7 December 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and launched invasions throughout Southeast Asia. Thailand was invaded at nine points. Despite a decade of military build-up, resistance lasted less than a day. Pibul acceded to Japan’s request for “passage rights”, signed a treaty with Japan and declared war on the Allies. Thailand’s ambassador in the US, MR Seni Pramoj, famously collaborated with the Americans, who refused to accept the declaration of war. Seni formed a Free Thai movement. In Bangkok, Pridi Banomyong, who had been marginalised by Pibul due to his attempted reforms, which were perceived as Communist, established a local resistance movement, the Seri Thai.

By 1944, Thailand’s initial enthusiasm for its Japanese partners had evaporated. The country faced runaway inflation, food shortages, rationing and black markets. The assembly forced Pibul out of office.

Prajadhipok visits Berlin in 1934.

Corbis

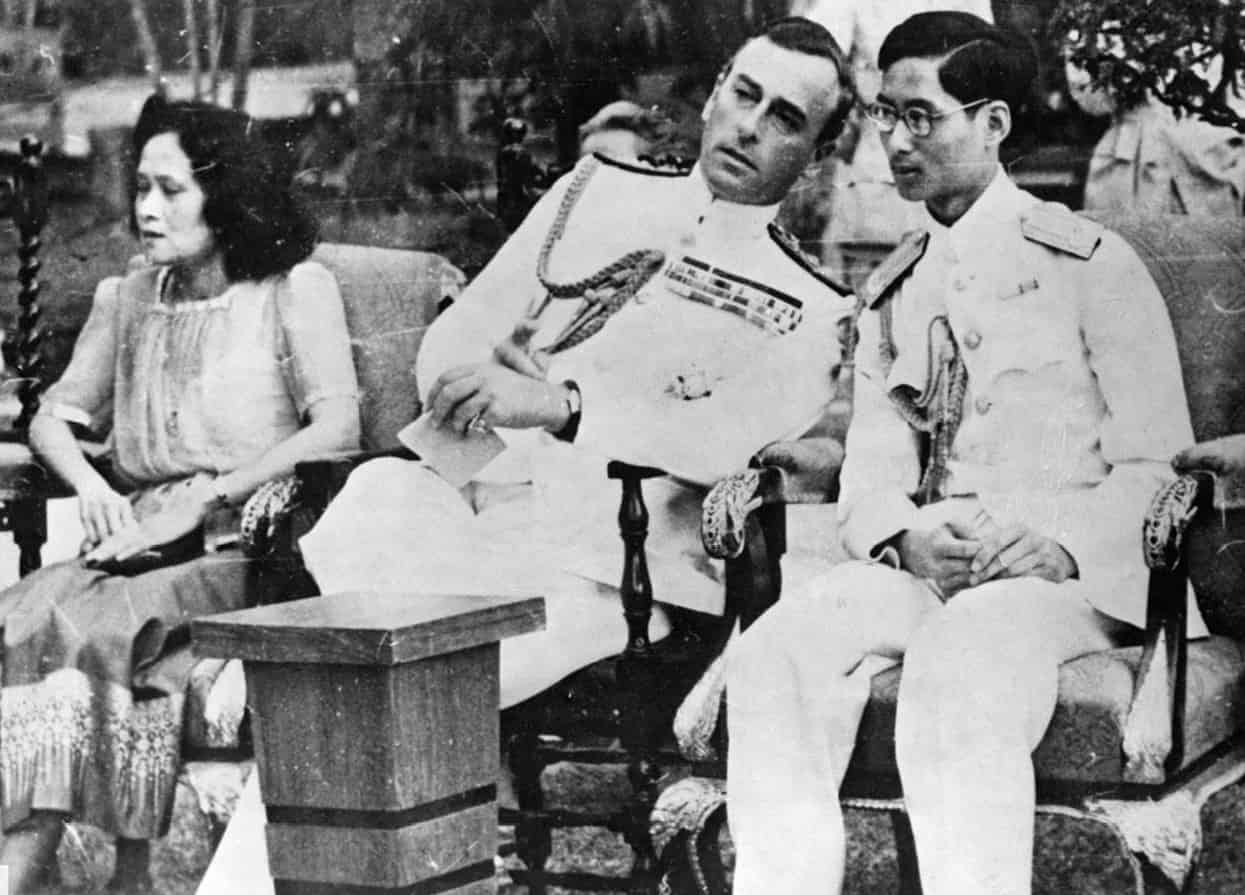

King Ananda Mahibol (Rama VIII) and Louis Mountbatten, the Allied Supreme Commander in South East Asia.

Corbis

When Thailand, then an ally of Japan, declared war on the US in 1942, the Americans refused to accept it, and a Thai resistance movement, the Seri Thai, was formed.

Pridi Banomyong’s struggle for power with Pibul and later Seni Pramoj lasted several years, and he became prime minister in 1946. In the same year, while on a visit to Thailand from school in Europe, the now adult King Ananda was found shot dead in his palace bedroom. Of the many rumours and conspiracy theories surrounding this incident, one of the most significant claimed that Pridi was involved. He resigned and the following year fled to Singapore after his house was attacked during a military coup. After a failed armed rebellion against the Pibul government in 1949, Pridi left for China, and never returned. The protracted murder trial of King Ananda’s alleged killers finally convicted and sentenced to death three palace aides for conspiracy, although a gunman was never formally identified. The circumstances of the king’s death have still not been satisfactorily explained; the incident is still discussed and most people have their own theories.

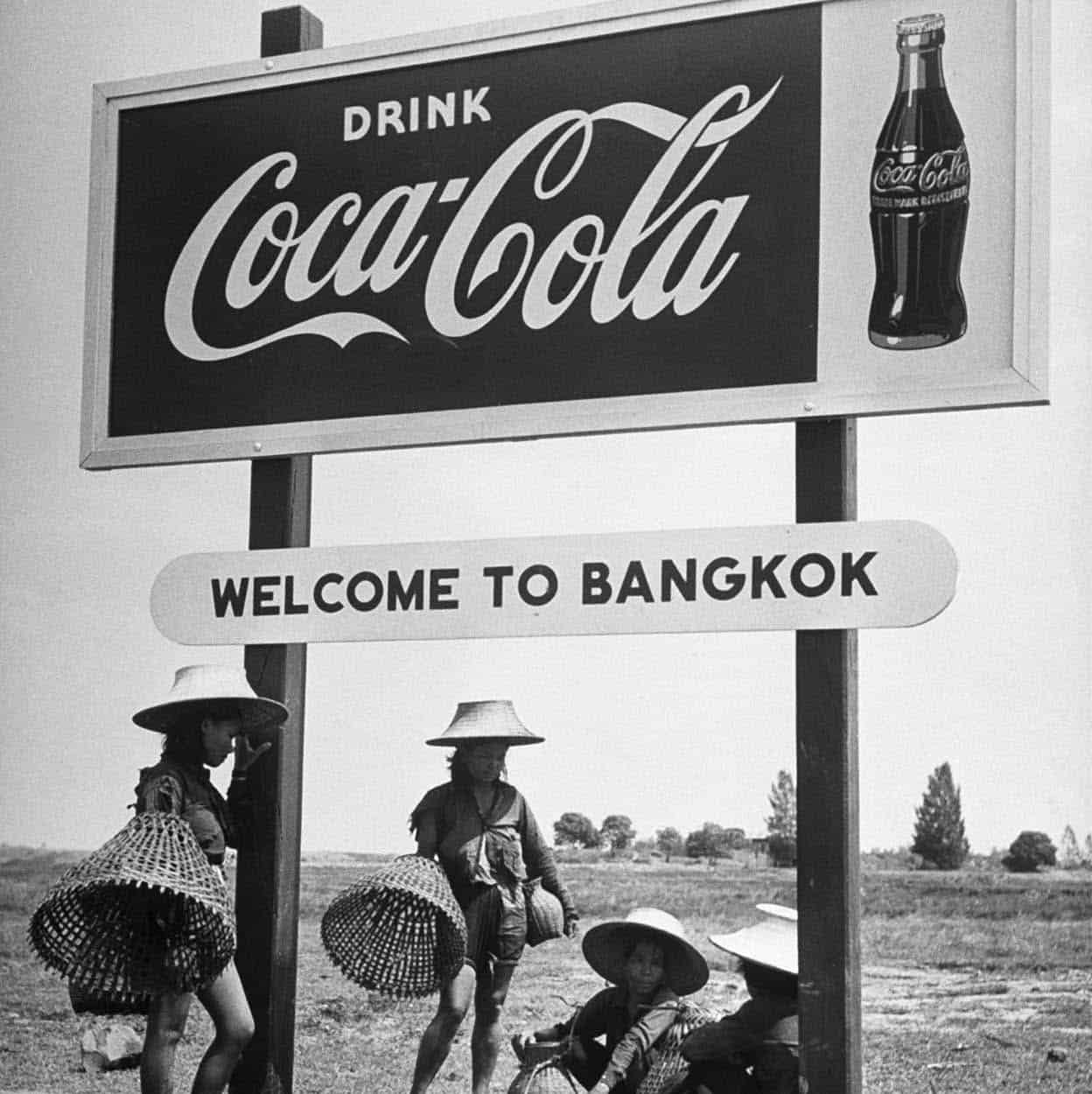

Billboard, c.1950.

Getty Images

Traffic Woes

The 1980s and ’90s saw the vertical growth of Bangkok. Its skyline changed dramatically but along with it came congested roads and notorious traffic jams. In the early 1980s, various government officials suggested solutions to ease Bangkok’s traffic problem. Eventually the ideas evaporated, mired in corruption or woefully poor cooperation between competing agencies – only to be recycled a year or two later. Thankfully, the situation has improved vastly with the construction of a complex network of elevated expressways. To ease traffic further, in 1999, Bangkok’s first mass transit system, the Skytrain, started operations, and in 2004 a metro line opened.

King Ananda was succeeded by his younger brother, Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX), (for more information, click here), who returned to Switzerland to complete law studies. He did not, however, take up active duties until the 1950s. By then, Thailand had been without a resident king for 20 years.

In 1957, a clique of his one-time protégés overthrew Pibul. Their leader, General Sarit Thanarat, and two cohort generals, Thanom Kittikachorn and Prapas Charusathien, ran the government until 1973, employing martial law. The military, which had steadily been gaining power, reached its peak of influence during these years. The generals’ ascendancy coincided with America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Large infusions of money flowed from the US to Thailand, America’s staunchest ally, resulting in a burgeoning economy. Health standards improved; the business sector expanded; construction boomed; the population swelled in response to new jobs; and a middle class began to emerge. And the generals, now called “The Three Tyrants”, used their power to amass huge personal fortunes. But the socio-economic changes also brought new aspirations to the population.

Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn at a news conference in 1971.

Corbis

The October 1973 uprising

Following the arrest of student leaders for distributing anti-government leaflets, protests broke out around the country, including 400,000 people at Bangkok’s Democracy Monument. Clashes on 14 October 1973 between troops and students left many students dead (the official figure was 77, press estimated 400). Under pressure from several influential factions, The Three Tyrants fled to the US.

Two subsequent elections produced civilian governments, but the fledgling democracy was hampered by the diverse interests of new political parties, labour unions and farming organisations. The middle class, originally strongly supportive of the student revolution, along with some of the upper class, came to fear that total chaos or a Communist takeover would emerge.

Soldier occupying Thammasat University during the 1976 student protests.

Corbis

The 1976 return of General Thanom, ostensibly to become a monk, sparked more student protests. After two were garrotted, allegedly by police, students occupied Thammasat University. On 6 October, police, troops and paramilitary organisations stormed the grounds, raping and killing many people. Within hours the army had seized power in a coup. Self-government had lasted but three years. Ironically, the civilian judge appointed to be prime minister, Thanin Kraivichien, turned out to be more brutal than any of his uniformed predecessors. Yet another military coup ousted Thanin in October 1977. For the next decade there was relatively moderate military rule, and under General Prem Tinsulanond the foundations were laid for new elections, which ushered in a civilian government.

Protesters march through the streets during the “Bloody May” crisis of 1992.

Corbis

Another military coup

After a bloodless military coup in 1991, spearheaded by General Suchinda Kraprayoon, the junta installed a businessman and ex-diplomat, Anand Panyacharun, as a caretaker premier until elections planned the following year. Anand earned plaudits for running the cleanest government in memory and is still a highly respected figure in Thai politics.

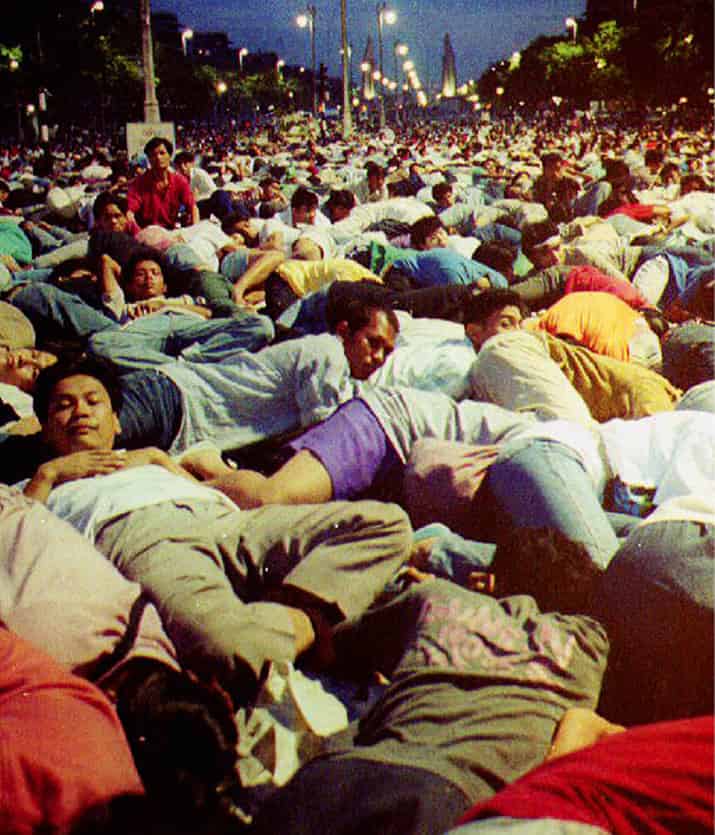

A political party newly formed by the junta won the most seats at the election, but General Suchinda unseated the intended prime minister and installed himself as leader. The middle classes protested, gathering at rallies, inspired by former Bangkok Governor Chamlong Srimuang, a figure who would have great impact on Thai politics into the new millennium. More than 70,000 people alone met at Sanam Luang on 17 May 1992. Late in the evening, soldiers fired on unarmed demonstrators. Killings, beatings, riots and arson attacks continued sporadically for the next three days. The Thai broadcast media, controlled by the government, were obliged to impose a news blackout, but owners of satellite dishes, along with viewers around the world, watched the coverage of “Bloody May”. The crisis ended when King Bhumibol intervened. A little later, the unrepentant Suchinda bowed out and left the country. The Democrat Party and other prominent Suchinda critics prevailed in the September 1992 re-elections.

Protesters are forced to the ground when government troops open fire during the “Bloody May” crisis of 1992.

Getty Images

Democracy prevails

Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai, considered honest but ineffectual, persisted for almost three years from 1992 to 1995, a record for a civilian government. Setting another record, he was not toppled by a coup. But by the end, Chuan had lost much of the goodwill of the pro-democracy groups that had lifted him to power.

Chuan battled constantly to keep his coalition working together. It finally disintegrated when some members of Chuan’s own party were implicated in a land-reform scandal. Elections in July 1995 brought an old-style politician, Banharn Silpa-archa, to the premiership. As the Thai press phrased it at the time, both Banharn and his party, Chart Thai, had a strong “reputation” for corruption.

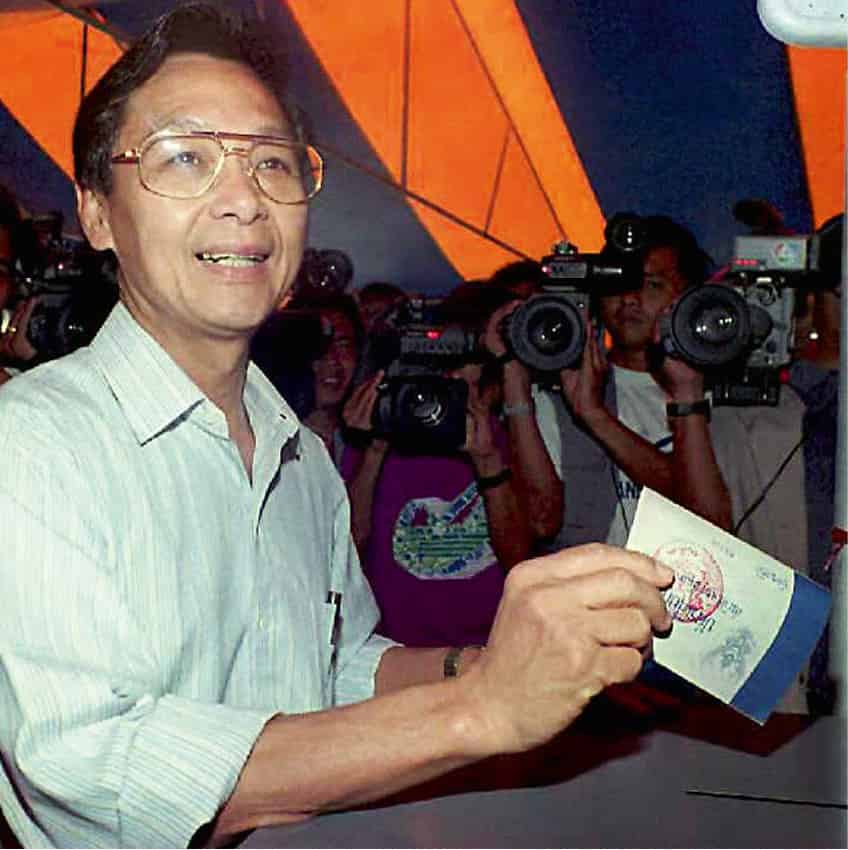

Leader of the New Aspiration Party, Chavalit Yongchaiyudh, who became Prime Minister in 1996.

Getty Images

Economic crisis

The Thai economy, which registered phenomenal annual growth rates for over a decade to emerge as one of the famous “Tiger” economies of Southeast Asia, suddenly saw the good times come to an end. By late 1996, inflationary pressures, a widening current account deficit and slower economic growth led to a censure motion against the 14-month-old government led by Banharn Silpa-archa. Elections held in November 1996 saw a coalition headed by the New Aspiration Party come to power. NAP leader Chavalit Yongchaiyudh became Thailand’s 22nd prime minister, but many of his partners in government were the same as in the previous administration and little was done to stem the economic rot that had set in.

By February 1997, ratings agency Moody’s had downgraded Thailand’s credit rating. A few months later, the government ordered the closure of 16 finance companies that were in the red. The final straw came shortly afterwards, on 2 July, when the Chavalit administration decided to drop the traditional currency peg in favour of a “managed float”. This had the disastrous double effect of sending the currency down in a devaluation spiral and making the foreign debts of local corporations skyrocket.

The pressure to float the baht was partly caused by aggressive attacks by foreign hedge funds; enormous sums from the country’s foreign exchange reserves were spent in its defence. In the end, the government was forced to ask the IMF for US$17 billion to help keep the country afloat. The crisis saw businesses go bankrupt and many thousands lose their jobs, due to closures or downsizing.

Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai casts his vote in the 1995 elections.

Getty Images

Amid all this, changes to Thailand’s constitution were promulgated on 11 October 1997 by the Chavalit government. It set up positive new measures for Thai democracy, including a bicameral legislature and independent bodies to monitor the government. The new document, however, was not enough to save the government, and Chavalit stepped down under intense public pressure in September 1998 as the country’s economic gloom deepened.

This brought in a Democrat government headed by Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai. After over a year of hard work, the economy, which had bottomed out, began showing gradual signs of recovery. The process was helped along by a banking reform package in August 1998 that helped boost confidence in the country among foreign investors. The government also pushed forward business laws to help speed up corporate debt restructuring.

The Thaksin administration

In 2001, general elections installed the populist billionaire entrepreneur Thaksin Shinawatra and his newly formed Thai Rak Thai (Thai Love Thai) party.

Thaksin’s governance proved almost immediately controversial. He faced, and successfully defended, charges of corruption; he was widely condemned after hundreds were killed in his “War on Drugs”; and he was slammed for suppressing the media. But his leadership was a breath of air to many. His “populist” approach saw loans and cheap health care for the poor, and he brought a swagger and confidence to Thailand’s self-perception on the world stage, famously dismissing international criticism on one occasion by declaring: “The UN is not my father”. However, as he became wildly popular in poorer rural areas, particularly in the north and northeast, his “CEO style” of government was increasingly annoying traditional powers in the country, centred in Bangkok.

Street celebrations in honour of King Bhumibol’s 80th birthday in 2008.

Getty Images

In 2005, an alliance of opposition interests formed, led by Chamlong Srimuang and former Thaksin supporter Sondhi Limthongkul. They united under the name the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), and began anti-Thaksin street demonstrations. They adopted the colour yellow to show allegiance to the monarchy. The movement intensified after Thaksin, already the richest man in Thailand, sold his telecommunications company to an arm of the Singapore government for US$1.9 billion and paid no tax.

Yet another coup

In response, Thaksin announced a snap election in April 2006. Opposition parties boycotted the process, and although Thaksin won again, he resigned as prime minister in the face of mass protests, appointing his deputy, Chidchai Wannasathit, as the new caretaker premier. Thaksin was plagued by claims of rigged bids for the new Suvarnabhumi Airport, lèse majesté against the beloved King Bhumibol, alleged vote-buying and a worsening Muslim insurgency in the south, which by then had claimed over 2,000 lives.

Following months of protests, the army staged a bloodless coup on 19 September 2006, when Thaksin was in New York attending a United Nations summit. Following up on charges of election irregularities, the new authorities banned 111 Thai Rak Thai officials from politics, including Thaksin, and froze his bank accounts in the country. As Thaksin lived in exile in London, his followers, calling themselves the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD), and wearing red shirts, launched protests against the military government. A Thaksin proxy, the People Power Party (PPP), won the next general election in December 2007, and Thaksin returned the following year, only to later skip bail on corruption charges and flee once again to London.

Anti-government “red shirt“ protesters in Bangkok’s main shopping district, April 2010.

Corbis

Red Shirt, Yellow Shirt

Meanwhile, the yellow shirt PAD demonstrations resumed. During late 2008, they occupied Government House, sometimes clashing violently with Thaksin supporters, and finally seized the airport, bringing the country to a standstill. In December that year, the courts disbanded the ruling party, and, in a deal largely seen as being brokered by the army, some key Thaksin allies jumped ship. The Democrat Party took office with Abhisit Vejjajiva as prime minister.

As befits a telecoms tycoon, Thaksin mobilised his followers with a series of satellite phone-ins and video links, launched internet sites, and began twittering on a daily basis. In April 2009, Red Shirt protests intensified. They disrupted the ASEAN Summit in Pattaya, causing several heads of state to be airlifted to safety, and Songkran riots erupted in Bangkok. In the same month, PAD leader Sondhi Limthongkul was shot, but survived the assassination attempt.

In a provocative twist, and revealing his links with regional powers were still significant, Thaksin was appointed as financial advisor to the Cambodian government late in the year. Tensions between Thailand and Cambodia were already high over the disputed lands around the Preah Vihear Temple on the Cambodian border. Troop numbers were increased and ambassadors recalled by both countries.

As the New Year approached, commentators were increasingly debating the possibility of civil war breaking out at some level, particularly as factions either within the army, or with strong army connections, began to reveal themselves as Thaksin supporters.

In February 2010, outstanding corruption charges against Thaksin were finally heard. The courts found him guilty of abuse of power and confiscated assets of B46 billion. Still immensely rich, Thaksin vowed to fight on.

Post-Thaksin life

In 2014, after successive Thaksin-backed governments win elections, under the new banner of the Puea Thai Party, led by his sister Yingluk, the opposition Yellow Shirts (and affiliated groups) stage mass demonstrations. Thaksin’s influence in politics wanes. Led by Suthep Thaugsuban, the opposition is successful in bringing enough chaos to the streets to allow for the army to stage another coup, ostensibly to bring calm to a precarious social and economic situation that has been volatile since 2006. General Prayut Chanocah is sworn in as the new leader of a military government with promises for elections within two years. Machinations and problems in the constitution writing process delay the initial timetable and elections are delayed until 2017. The new constitution is eventually passed via a nationwide referendum which leaves the possibility of an unelected prime minister being appointed after fresh elections.

As a result of this period of political instability, Thailand sees a decline in foreign investment and enters a period of economic downturn.

King Bhumibol’s passing

After a long illness, King Bhumibol passes away on 13th October 2016. The country starts a year-long period of mourning. The authorities ask for entertainment venues to tone down as a mark of respect and people are encouraged to wear black or dark clothing. Bhumibol’s son, Maha Vajiralongkorn, is crowned king 50 days after his father’s death.

The Monarchy

Thailand is officially a constitutional monarchy, but the king’s importance in the nation’s life is apparent everywhere, from official buildings to people’s homes.

Although an army-led bloodless coup in 1932 removed the absolute powers of Thailand’s King Prajadhipok (Rama VII), the monarchy remains one of the most influential institutions in the land, and is omnipresent.

The monarchy is represented by the blue bar of the Thai tricolour (red stands for the nation, white is religion), while photographs of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej adorn government buildings and public spaces, and legal regard is enshrined in lèse majesté laws, which carry a maximum penalty of seven years imprisonment for anyone convicted of insulting the royal family.

King Bhumibol ascended the throne in 1946, following the death, in mysterious circumstances, of his brother King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII), and was, until his death in 2016, the world’s longest-reigning monarch. Respect for King Bhumibol was enhanced by a sense of his morality and representation of traditional Thai values in the face of corrupt governments. He was seen as the ameliorating figure in the turbulent conflicts of 1973, 1976 and 1992, when the army and police killed many civilians. He endured pockets of unprecedented criticism from some supporters of Thaksin Shinawatra, who believe the king and other elements of the traditional elite were involved in the overthrow of the fugitive ex-prime minister. The lèse majesté laws have been used more widely than usual during recent years.

Books and films about King Mongkut based on the memoirs of Anna Leonowens, titled The English Governess at the Siamese Court, are all banned in Thailand. These include the Hollywood favourite The King and I, starring Yul Brynner. Leonowens was a tutor of the royal children, but is regarded as having misrepresented both her role and life in the palace.

Radio and TV stations play the national, or King’s anthem, regularly, as do cinemas and railway and bus stations, when people will stand respectfully for the duration. Indeed, his subjects had a famed love of the king and would generally take offence at anyone speaking ill of the monarchy. Photographs of the late King Bhumibol are widespread in shops and homes, along with those of his predecessors, particularly King Mongkut and King Chulalongkorn, who were the modernisers of Thailand in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

King Bhumibol was seen as a man of the people, particularly through his work in the King’s Project, which is concerned with the development of small agricultural communities. His subjects were also genuinely proud of his achievements in the field of jazz (for more information, click here); the king penned many tunes, including the humorously named “HM Blues”. The nation’s monarchist fervour saw crowds turn out in huge numbers for the king’s birthday celebrations in Sanam Luang in December.

On 13th October 2016 the king passed away after a long illness. His heir apparent, the Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, succeeded him on the throne on 1st December 2016.

Thailand’s new king, Maha Vajiralongkorn, or Rama X.

STR/AP/REX/Shutterstock