Ratification in States Generally Opposed to the Constitution

THE Constitution having been ratified by the requisite nine states, these states could now proceed to organize the government of the United States. The five weakest of them had ratified by large margins, as had been expected. The four stronger ones which the Federalists had believed could also, with sufficient effort, be brought to ratify had likewise fulfilled expectations. There now remained four strong states in which obviously there were large numbers of persons who were satisfied with the way their problems were being met under the Articles of Confederation.

These states were Virginia, New York, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. In each of them it was expected that ratification, if it was achieved at all, would be attended by considerable difficulty. The Federalists had the upper hand now because they had a nine-state Union, but the possibility that one or even all of these remaining states might refuse to ratify was not at all remote. Their ratification was essential to the success of the Union, if only because their exclusion would divide the nation’s territory into three non-contiguous parts.

VIRGINIA’S ratification was almost as important to the Federalists as that of the first nine states. Without those nine states the Constitution could not be put into operation. Without Virginia, George Washington, the man whose unrivalled prestige made him the obvious choice for the office, could not be elected president. After a brilliant contest between powerful strategists Virginia ratified the Constitution on June 25, 1788. The victory of the Federalists was now all but complete.

Because of the refusal of George Mason and Edmund Randolph to sign the Constitution at the close of the Philadelphia Convention, even those who had little knowledge of the state’s internal affairs expected ratification in Virginia to be difficult. It was feared that a ratifying convention might not even be called. But this obstacle did not materialize. The Virginia legislature issued a call for a convention immediately after it convened in October, 1787, before the serious debate on the issue began. Despite the fact that of the members of the legislature who were later to serve as delegates to the convention, exactly half were to vote against ratification, the call for a convention was issued unanimously. There was some dispute over details. A bill originating in the House called for elections in March and the opening of the convention in May; the Senate proposed amendments providing that the election dates should coincide with the state’s traditional April elections, and that the meeting of the convention be advanced to June. These amendments the House accepted. The battle for ratification was now about to begin.1

A full seven months was occupied in campaigning for the elections to the convention. The opponents of the Constitution clearly had an edge in the published propaganda. Mason’s lengthy and solemn statement of his objections, Randolph’s letter to the legislature explaining why he had refused to sign the document, and Richard Henry Lee’s masterful letter to the governor and the arguments he presented in newspapers and pamphlets were widely spread. Neither the barrage of newspaper propaganda from the northward, the anonymous writings on behalf of ratification in the newspapers of Norfolk, Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Alexandria, nor even the classic Federalist Papers, imported from New York and circulated in Virginia in quantity, could match the influence of these open declarations of Mason, Randolph, and Lee.2

The printed word reached only a limited audience in the vast spaces of Virginia, however, and forty-six of the delegates to the convention were to come from counties west of the Blue Ridge, where there was almost no circulation of printed matter.3 More important were oral discussions, the focusing of campaigns on particular areas, and the careful selection of candidates, and in these matters the friends of ratification were perhaps shrewder than their opponents. One technique which they used with signal success was to induce retired military heroes, whom they assumed would be under the great Federalist influence of George Washington, to become candidates for seats that would otherwise be likely to go to men who were regularly elected to the legislature and who it was assumed would be under the influence of the great anti-Federalist Patrick Henry.4

When the vigorous campaign was over and election returns were in, the Federalists had apparently won a clear victory. A careful Federalist survey made shortly after the elections showed that eighty-five candidates, exactly half of the total, had been elected as Federalists. Sixty-six had been elected as anti-Federalists and three were considered “doubtful.” With respect to sixteen delegates, twelve from Kentucky and four from the Trans-Alleghany area, it was not known what instructions they had received nor what their attitudes were. The task of the ratificationists appeared to be simply to hold their own and win one of the sixteen westerners. By the time the convention met, their position was stronger and victory seemed assured, for Edmund Randolph, who had been counted as an opponent, had changed his mind and announced his support of ratification.5

No one in the Federalist camp was overconfident, however, for it was impossible to ignore the almost magical power of Patrick Henry. With his prestige, his inspiring oratory, and his genius for creating and capitalizing on a dramatic moment, Henry was a formidable opponent. He was supported by William Grayson, a lawyer of prestige who had great personal influence with the half dozen men in the convention who had served in his regiment during the war. Colonels Benjamin Temple and Robert Lawson, both heroes of the war, and Theodorick Bland, vice-president of the Virginia Society of the Cincinnati, were expected to help Grayson break the military phalanx in the Federalist ranks. Finally, there was George Mason, renowned as the framer of the Virginia Bill of Rights, a man with enormous personal prestige. The strongest assets of the anti-ratificationists were age, prestige, and Patrick Henry.

The Federalist leaders devised their strategy with painstaking thoroughness. Realizing that no one man was a match for Henry, they worked as a team. As his equal in prestige they could offer Edmund Pendleton, his foe since the celebrated legislative battles of the 1760’s, and George Wythe, beloved mentor of a half dozen lawyers in the convention. To deal with Henry’s logic they employed Madison and Marshall. When Henry shifted his ground and talked of Virginia affairs, they countered with George Nicholas. For the dirty work, the infighting, they employed one of the few men who dared battle Henry in that area, Edmund Randolph.

Despite the careful plans, the keen strategy, and the persuasive oratory of the Federalists, Henry and the other anti-ratificationists managed to convert three of the elected Federalists and enlist ten of the twelve Kentucky delegates. The conversion of the three Federalists Henry apparently achieved with one brilliant speech portraying the destruction of liberties that would ensue from ratification, a portrayal so vivid that one witness “involuntarily felt his wrists to assure himself that the fetters were not already pressing his flesh.” The support of the Kentuckians was won by a dramatic introduction of the question of the proposed Jay-Gardoqui Treaty, providing for the surrender of navigation of the Mississippi to Spain. The Federalists managed to enlist the four Trans-Alleghany delegates, one of the three “undecided” delegates, and two of the Kentucky delegates. When the final vote was taken on June 25, the Constitution was ratified by a slim margin, the vote being 89 votes to 79.6

It is evident even from a reading of the debates in the convention that there is no simple explanation of the movement for ratification in Virginia. To explain the votes in full would be to write the history of Virginia from 1758 to 1788. Much light can be shed on the question, however, by an analysis of the origins and development of the principal issues upon which Virginia’s vote turned.

These must be considered in the light of Virginians’ attitude toward their state. Virginia has been called the Prussia of the American Confederation. To Virginians it was even more than that. So strongly imbued were they with state consciousness and pride that many of them applied the term “my country” only to Virginia, using various other terms to signify the United States.7 This state particularism, of long standing, had been augmented after the war when the state, now free from the commercial and political shackles that had bound it under the crown, enjoyed an unprecedented wave of prosperity; everyone except the planters on the depleted tobacco lands of the tidewater was inspired with a confidence Virginians had never known before.8

The task of the advocates of ratification was to overcome this state particularism. The problem of their opponents was to preserve and augment it.

Seven basic sets of factors may be profitably examined as possible determinants of the votes in the convention: the backgrounds of the delegates, the war experiences of various sections of the state, personal influences, military connections, the effects of the treaty of peace, Robert Morris, and the Mississippi River question.

Several of the delegates were not native Virginians. Four of them had been born and had grown up abroad, a fifth came from Pennsylvania, and a sixth had been taken to England by his loyalist parents as a young man and had returned after the peace. None of these men had the passionate provincial feelings of the other delegates, and all six were unwavering friends of ratification.

A second factor was the lesson the war had taught respecting military defense. Those places that had suffered damages from the war at first hand were acutely conscious of their military vulnerability, and their provincialism withered in the face of the realization that only a strong union could provide military security. The greatest wartime losses had been suffered by the counties of York, James City, Warwick, Elizabeth City, and Gloucester, which had been the battlegrounds preceding and during Yorktown, and the borough of Norfolk, which had been the victim of naval warfare. Almost every plantation in these counties had been burned to the ground. These areas sent eleven delegates to the convention, ten of whom voted for ratification.9

A third factor was the personal influence of some of the delegates. A complex network of lesser influences pervaded the convention: Randolph, Madison, Nicholas, Pendleton, and Wythe on one side and Grayson, Benjamin Harrison, and Mason on the other had personal followings of varying sizes. In the main, however, the contest was one between the rival influences of two giants, George Washington and Patrick Henry. Throughout the continent as a whole Washington enjoyed a prestige with which no other man’s could compare. In Virginia, however, Henry’s influence, except among the military, was probably greater than Washington’s. At least two dozen of the delegates were men who had, over the past six years or more, consistently followed Henry’s lead on virtually every issue in the legislature, and Henry’s prestige extended his influence far beyond his immediate political following. Except among the few men with whom he regularly corresponded, Washington’s influence outside the military is difficult to measure.

Military service also played a role in the contest over ratification. The Federalists, as has been said, had selected as many military men as possible as candidates for the convention. Forty-six of the eighty-nine Federalist delegates had been officers in the Revolutionary armies, and twenty-three more had been militia officers, about half of whom had seen combat. Henry Lee summarized Federalist logic in the choice of military candidates in a speech attacking Henry’s appeal to provincialism. One would think, Lee said, “that the love of an American was in some degree criminal, as being incompatible with a proper degree of affection for a Virginian. The people of America, sir, are one people. I love the people of the North, not because they have adopted the Constitution, but because I fought with them as countrymen, and because I consider them as such.” 10

Despite the fact that three-fourths of the delegates who favored ratification had seen military service, however, it is possible to overestimate this factor. The anti-ratificationists countered with the influence of Grayson and other distinguished veterans, and with Henry’s eloquent championing of the superiority of the civil authority over that of the military. The presence of so many military men in the Federalist ranks actually frightened some delegates and made them receptive to Henry’s vivid prognostication of armed hordes marching under the banner of the new government to subvert Virginia liberties. As a result of these counter-influences, thirty-five men who had served as officers in the Revolutionary armies voted against ratification.11

The fifth set of factors, the issues relating to the treaty of peace, was the most complex of all. Two sections of the treaty, one providing for the evacuation of the British military outposts in the Northwest Territory and the other for the restoration of property to legitimate owners on both sides, were of immense significance to Virginia. These provisions affected Virginians for four reasons: 1) The Northwest posts were an obstacle to the westward migration of Virginians, and were therefore inimical to the interests of residents of the Valley and Trans-Alleghany regions, and to those of the land speculators who held titles to vast tracts in the Territory. 2) Virginia had lost some thirty thousand slaves, more than a tenth of the total number in the state, through confiscation by the British army. 3) Virginia had confiscated large quantities of British and loyalist property, principally the vast Fairfax estate in the Northern Neck, around Alexandria. 4) Virginia planters owed British merchants more than two million pounds sterling (nearly ten million dollars) for prewar purchases. The treaty affected Virginians favorably with respect to the first two matters, unfavorably with respect to the other two.12

During the 1780’s the treaty had been disregarded on all four matters. The British had refused to evacuate the posts and to restore or make restitution for the slaves, the Virginians had made no effort to restore the property they had confiscated and had passed legislation prohibiting the collection of the debts. During the war they had gone so far as to permit debtors to write off their obligations by paying nominally equivalent sums of depreciated paper money into the state treasury and twice, in 1784 and 1787, they had expressly refused to open their courts to suits by British creditors.

The Constitution promised an end to the treaty holiday. In theory, it made treaties the supreme law of the land; in practice, it established a government which could require the British to abide by the treaty and which would open its own courts to suits by British subjects seeking restoration of their property.13

One of these four issues, that concerning the Northwest posts, was a relatively simple one. Few of the delegates from the Valley and Trans-Alleghany regions were debtors to British merchants, and all of them resented the presence of the British across the Ohio River in the Northwest Territory. These areas sent twenty-eight delegates to the convention, twenty-seven of whom voted for ratification.14

The other issues arising from the treaty were extremely complex. The areas that had suffered most from British depredations were, in the main, the very same areas in which debts to British merchants were most heavily concentrated. The area that had the most to lose from a restoration of sequestered property, the Northern Neck, was the area where Washington lived and exerted his greatest influence. Attitudes with respect to the treaty varied with individual attitudes toward the British and the loyalists, which in turn were born of the amount of personal suffering endured at the hands of the British as well as a number of other factors.

In general, there were four shades of opinion regarding the treaty. One small group favored unconditional obedience to its terms on the part of the United States, either because they considered it a matter of national honor or, more often, because they were pro-British. A second group, which included a large number of the inhabitants of the western regions, favored making strong concessions to the British as a show of good faith, in the hope that the British would respond by abiding by the treaty themselves. A third and larger group would refuse to abide by the treaty until Britain made overtures indicating a clear intention to abide by all its terms. This group was subdivided into two factions: one wanted to work actively through Congress for British compliance and the other wanted merely to wait. The fourth group was unconditionally opposed to complying with the disputed parts of the treaty then or at any time in the future.15

While there existed these four shades of opinion and the lines separating them were not clearly drawn, in the ratifying convention the delegates could vote only one of two ways, yes or no. This being the case, it was obvious that the influence of the treaty in shaping attitudes toward ratification would depend largely upon the ability of partisan leaders to convince the delegates of the safety or insecurity of their interests. On the question of the property confiscated by Virginia, the Federalists, under the leadership of John Marshall—who was himself deeply interested financially in the sequestered Fairfax estate—obviously were the more convincing. All the delegates from the Northern Neck, with the lone exception of George Mason, voted for ratification.

The question of the British debts was not settled with such unanimity. Leaders on both sides had taken advantage of the wartime act to write off old debts by paying depreciated paper to the state. Federalists such as Pendleton, Lee, Fleming, Alexander White, Zachariah Johnston, Paul Carrington, Marshall, Thomas Walke, and Robert Breckenridge had made such payments, as had Harrison, Henry, and Joseph Jones of the opposition.16

During the 1780’s seven votes were taken in the House of Delegates on the various issues concerning the treaty. On only three of these was the issue clear-cut. On November 17, 1787, a proposal was made that all legal obstacles to the collection of the debts be removed, provided this could be done equitably and with some order. A comparison of the votes on this question with the vote on ratification seven months later is of considerable interest.17

The delegates who were later to vote for ratification opposed this proposal, twenty-two votes to six. The delegates who later voted against the Constitution voted, despite the opposition of both Henry and Mason, in favor of the resolution, sixteen votes to ten.

The counties east of the Blue Ridge which were to favor ratification cast fourteen votes in favor of the proposal and twenty-one against it. The counties east of the Blue Ridge which were to oppose the Constitution voted for the proposal, twenty-three to fourteen. From the four counties which were to be divided on ratification, three legislators later attended the convention, two of whom voted for the proposal. In the state as a whole, the counties that were to favor ratification opposed the proposal forty-four to twenty, and the counties that were to oppose ratification favored the proposal, twenty-eight to twenty-one.

On the same day, November 17, a vote was taken on a resolution that Virginia refuse to comply with the treaty until every other state passed a blanket law repealing all acts contrary to the treaty. This was virtually impossible of attainment, so in effect the proposal was to refuse to abide by the treaty at all, under any circumstances. The delegates who later voted for the Constitution supported this resolution, twenty-three to five, and the delegates who were to oppose ratification voted against the resolution, twenty to four. Later in the day the proto-Federalists voted, four to twenty-three, against a proposal that Virginia comply with the treaty if Britain indicated its intention of doing so. The anti-Federalist delegates-to-be supported this measure, twenty to six.

A great majority of the proto-Federalists, then, were opposed to the collection of the debts on any terms. On the other hand, sixteen of the twenty-six delegates who later opposed the Constitution favored collection of the debts without qualification, and four more favored collection if Britain could be induced to abide by the treaty.

It is clear, then, though it may be paradoxical, that if there was a debtors’ faction in Virginia politics, it was largely identical in personnel with the pro-ratificationist group.18

The sixth major element influencing the movement for ratification was the connection of the Virginia movement with Robert Morris of Philadelphia. That gentleman had been suspect in Virginia since his reign as superintendant of finance in 1781-1783, and Virginians were inclined to be hostile to any movement in which he had a part. Perhaps a more important cause of their antipathy was born of Morris’ contract with the corrupt French Farmers-General, giving him a monopoly of the French tobacco trade. Though shrewd Scotch-Virginian traders ultimately found ways to circumvent the monopoly and to trade on a large scale directly with France, Morris was temporarily able to force the price of tobacco in Virginia down from forty shillings to twenty-two shillings a hundredweight, and the experience won him the hostility of most Virginians. His signature on the Constitution did nothing to make the document more palatable to them.19

The seventh and final major element was the question of the navigation of the Mississippi, which has been previously mentioned and is discussed more fully on pages 366-367.20

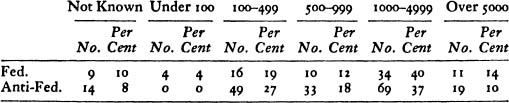

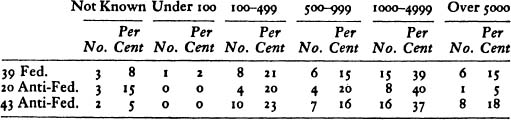

From the foregoing it would appear that only one economic consideration (navigation of the Mississippi) had a decisive influence on the final votes in the ratifying convention. The votes cut across all other economic issues in no meaningful pattern whatever; the decision did not turn on such questions. Furthermore, study of the occupations and property holdirigs of the members of the convention demonstrates that there was no line of division on the basis of individual property holdings. As the following tabulation shows, the property holdings of ratificationists and anti-ratificationists were virtually identical except that more small farmers from the interior supported ratification than opposed it.21

ECONOMIC INTERESTS OF DELEGATES VOTING FOR RATIFICATION

One delegate voting for ratification, Levin Powell (Loudon), was a merchant. The amount of his stock in trade was not ascertained, but one sloop belonging to him appears regularly in the manuscript Naval Officer Returns—that is, the customs office records of Virginia—for the period. He also owned 1,836 acres of land in five parcels, valued at £464. His personalty consisted of 22 slaves above the age of twelve, 18 horses, 24 cattle, and a two-wheeled chair (1787). He held $321 in continental securities.22

Seventeen were lawyers. Their property holdings were as follows.

John Blair (York), whose interests have previously been sketched in connection with his attendance at the Philadelphia Convention (page 74, above).

James Innes (Williamsburg), 200 acres valued at £92 10s. in York County (1786), no city property, 15 adult slaves (that is, slaves above the age of twelve) in Williamsburg, a cow, 3 horses, and a two-wheeled carriage (1786).

George Jackson (Harrison), amount of land unknown; 3 adult slaves, 8 horses. Jackson owned continental securities on which he received $59.40 interest payments in 1788.23

James Johnson (Isle of Wight), 300 acres valued at £88 15s.; 5 adult slaves, 4 horses.24

Gabriel Jones (Rockingham), 1,102 acres in Augusta County, 1,004 acres in Rockingham County, and 650 acres in Spotsylvania, having a total value of £996 17s. 10d.; 16 adult slaves, 6 horses, and a two-wheeled carriage. Jones owned $399.97 in continental securities.25

James Madison, Jr. (Orange), whose interests are described on pages 72–73.

Humphrey Marshall (Fayette), 4 slaves, 10 horses. The land books for Fayette County (Kentucky) are missing; in all likelihood Marshall’s total landholding was the 4,000-acre bounty he had been granted for war service.26

John Marshall (Henrico), no taxable personal property. The land books for his county are no longer extant, but Marshall owned 4,000 acres of Kentucky land that had been granted to him as a bounty for war service. He owned $6,205 in state securities.27

Andrew Moore (Rockbridge), 610 acres valued at £154; 5 adult slaves.28

George Nicholas (Albemarle), 3¼town lots with annual rentals totaling £90 and 1,122 acres valued at £282 3s.; 22 adult slaves, 15 horses.29

George Parker (Accomac), 470 acres valued at £137 19 S .; no slaves or other personalty.30

Edmund Pendleton (Caroline), 3,875 acres valued at £975 6s.; 44 adult slaves, 21 horses, one chariot; listed in 1787 as the owner of 105 head of cattle.

Edmund Randolph (Henrico), whose interests are listed on pages 74-75. Charles Simms (Fairfax), 11 acres valued at £ 11 11s.; no slaves, 2 horses. Simms owned $1,816 in state securities and was speculating in western lands, having acquired at least 16,000 acres in military bounties from various individuals.31

Archibald Stuart (Augusta), 440 acres valued at £82 5s.; one slave, 2 horses. Stuart owned continental securities on which he was paid $77.30 interest in 1788.32

Alexander White (Frederick), 664 acres valued at £597 12s.;9 adult slaves, 9 horses, a four-wheeled phaeton. White owned $1,619 in state securities.33

George Wythe (York), whose interests are sketched on pages 73-74.

Five were physicians:

William Fleming (Botetourt), 2,398 acres in Botetourt and 400 acres in Buckingham, with a total value of £386 19s.; 7 adult slaves, 11 horses.34

Walter Jones (Northumberland), 636 acres valued at £182 17s.; 25 adult slaves, 8 horses, a four-wheeled phaeton; $485 in continental securities.35

Miles King (Elizabeth City), half of a town lot with annual rent of £ 26 10s. and 604 acres in five parcels, having a total valuation of £356 18s .36

David Stuart (Fairfax), 1,665 acres valued at £723 13s.; 14 adult slaves, 4 horses; $2,024 in continental securities.37

James Taylor (Norfolk County), 165 acres valued at £120 6s.; 4 adult slaves, 3 horses; $1,443 in continental and state securities.38

Two were ministers:

Robert Andrews (James City), who owned neither land nor slaves in James City County, but who owned two town lots in Williamsburg with a yearly rent of £16 10s. He also owned $13,030 in various forms of securities, most of them state securities.39

Anthony Walke (Princess Anne), who owned 3,881½ acres in three parcels in Princess Anne and 50 acres in Norfolk County, having a total value of £1,689 15s ., and 12 town lots of unknown value; 48 adult slaves, 23 horses, a four-wheeled phaeton.40

Sixty-four were planters and lesser farmers:

John Allen (Surry), 2,000 acres in James City County and 200 acres in Surry, having a total value of £2,004 3s.; owned no slaves in his own name. In 1787 Allen had owned continental securities on which he received $554.70 interest, but by 1791 the total face value of his securities was only $105.41

Burdet Ashton (King George), 350 acres valued at £110 16s.; 34 adult slaves, 13 horses.

Burwell Bassett (Newkent), 5,880 acres in four parcels, having a total value of £3,729 9s.; 81 adult slaves, 23 horses, a coach, a phaeton, and a chair.

Benjamin Blount (Southampton), 1,450 acres valued at £ 1,026 13s.; 19 adult slaves, 12 horses, and a two-wheeled chair.42

Robert Breckenridge (Jefferson), whose landholdings consisted of the 3,110-acre bounty he had received for war service.43

Humphrey Brooke (Fauquier), 400 acres valued at £257 18s.; no slaves or other personalty.

Rice Bullock (Jefferson), whose land consisted of his 2,666-acre military bounty.44

Nathaniel Burwell (James City), 5,608 acres in Frederick County, 1,800 acres in York County, and 1,288 acres in James City County, having a total value of £7,886 3s ., and a 5400-acre tract in Kentucky received as a military bounty; 21 adult slaves and 19 horses on the Frederick County plantation and 34 slaves, 10 horses, a chariot, and a two-wheeled carriage on the James City County plantation; $307 in state securities.45

William Overton Callis (Louisa), 660 acres valued at £343 15s ., and a 4,000-acre tract in Kentucky received as a military bounty; 10 adult slaves, 3 horses.46

Paul Carrington (Charlotte), 1,815 acres valued at £1,817 17s.; 33 adult slaves, 21 horses, and a two-wheeled chariot; $891 in state securities.47

William Clayton (Newkent), 1,808 acres valued at £1,055 8s.; 23 adult slaves, 16 horses, one chair.

George Clindinnen (Greenbriar), five parcels totaling 3,140 acres, valued at £628 17s . (1789); 2 adult slaves, 9 horses.

John Hartwell Cocke (Surry), 1,377 acres valued at £987 18S .; 22 adult slaves, 6 horses, a four-wheeled chaise; two continental certificates, one having a face value of $454 and the other of $298. On the latter Cocke received $54 for three years’ back interest in 1786.48

Francis Corbin (Middlesex), 200 acres valued at £196 13s.; 14 adult slaves, 5 horses.

William Darke (Berkeley), 4 adult slaves, 15 horses. The records of land-holdings in his county are no longer extant, but it is known that Darke had received 8,660 acres in bounties for military service. He also owned $4,078 in state securities.49

Cole Digges (Warwick), 3,013 acres in Warwick and 560 acres in James City County, total value £1,837 18S., and 2,666 acres of Kentucky land received as a bounty for military service; 34 adult slaves, 20 horses, a two-wheeled chair.50

Littleton Eyre (Northampton), 1,504 acres valued at £752; 48 adult slaves, 23 horses.

Daniel Fisher (Greensville), 752 acres valued at £419 13s.; 43 adult slaves, 37 cattle, 14 horses, and a two-wheeled chair, all owned jointly with three other men; $442 in continental securities.51

William Fleet’ (King and Queen), 296¼ acres valued at £307 7s.; 7 adult slaves, 6 horses.

Thomas Gaskins (Northumberland), 700 acres valued at £575 8s . and 8,832 acres of Kentucky land received as a bounty for military service; 21 adult slaves, 9 horses, and a four-wheeled phaeton; $358 in continental securities, on which he received $60 for three years’ interest in 1787.52

James Gordon (Lancaster), 686 acres valued at £359 14s.; 35 adult slaves, 10 horses, a four-wheeled post chaise, and a chair.

James Gordon (Orange), 36 adult slaves, 14 horses; no land is listed in Gordon’s name in the Orange County Land Books. One of the two James Gordons owned continental securities on which he received $162 interest in 1787.53

Ralph Humphreys (Hampshire), landholdings unknown; no slaves, one stud valued at £1 5s . for a season’s coverage.

Zachariah Johnston (Augusta), 697 acres in Augusta valued at £211 15s. and 440 acres in Botetourt valued at £594; 3 adult slaves, 16 horses; continental securities on which he received $30 interest in 1787.54

Samuel Kello (Southampton), 700 acres valued at £317 18S.; 13 adult slaves, 6 horses, and a post chaise.

Henry Lee (Westmoreland), 955 acres in Fairfax and 1,645 acres in Westmoreland having a combined value of £ 1,161 13s ., one town lot with £5 yearly rent, and 8,239 acres in military bounty lands; 50 adult slaves, 6 horses, 50 cattle, and a four-wheeled chariot (1787).55

Thomas Lewis (Rockingham), 1,960 acres valued at £645; no slaves or other taxable personalty.

Warner Lewis (Gloucester), 3,024 acres valued at £3,729 (1787); 153 adult slaves, 45 horses, 224 cattle, one post chaise, and one chair; $4,672 in continental securities.56

William McClerry (Monongalia), one slave, one horse; the land books for his county are no longer extant.57

Martin McFerran (Botetourt), 319 acres valued at £526; no slaves or other taxable personalty; continental securities on which he was paid $41.50 interest in 1787.58

William McKee (Rockbridge), 134 acres valued at £ 5; 4 slaves, 6 horses,

William Mason (Greensville), 828 acres valued at £ 565; no slaves, 2 horses. Thomas Matthews (Norfolk Borough). No tax returns for the borough as distinct from the county exist for these early years, and Matthews’ name does not appear on the county listings. He owned $524 in continental securities.59

Wilson Cary Nicholas (Albemarle), no landholdings recorded; 41 adult slaves, 21 horses, and a phaeton.

David Patteson (Chesterfield), 810 acres valued at £435 7s . (1789), 28 town lots with a yearly rent of £ 58 14s.; 14 adult slaves (1789), 9 horses, a phaeton, and one stud horse; continental securities on which he received $20 interest in 1786. Patteson was opposed to ratification and he voted with the anti-Federalist minority for a proposal to ratify conditionally. This failing, he voted for ratification.60

William Peachey (Richmond), 500 acres valued at £631 5s.; 39 adult slaves, 8 horses, 42 cattle (1786); $805 in continental securities.61

Martin Pickett (Fauquier), 1,063 acres valued at £403 8s. ; 17 adult slaves, 13 horses.

John Prunty (Harrison), size of landholdings unknown; no slaves, 5 horses.

Willis Riddick (Nansemond), 500 acres valued at £395 16s . and 4,000 acres of western land received as a bounty for war service.62

Jacob Rinker (Shenandoah), 478 acres valued at £111 1OS.; no slaves, 34 cattle, 10 horses (1787).63

William Ronald (Powhatan), 3,074 acres in Powhatan and 1,370 acres in Goochland, total value £2,218 17s.; 48 adult slaves, 28 horses, a phaeton in Powhatan, and 2 slaves in Goochland.

Abel Seymour (Hardy), landholdings unknown; 2 adult slaves, 9 horses. Solomon Shepherd (Nansemond), 529 acres valued at £698 14s.; taxable personalty unknown; $1,017 in continental securities.64

Thomas Smith (Gloucester), 630 acres valued at £345; 31 adult slaves, 10 horses, and a phaeton; $268 in continental securities.65

Adam Stephen (Berkeley), data on landholdings unavailable; 29 adult slaves, 40 horses; continental securities on which he was paid $614 interest in 1787.66

John Stringer (Northampton), 400 acres valued at £200; 11 adult slaves, 5 horses; $704 in continental securities.67

John Stuart (Greenbriar), 2,100 acres valued at £300; 6 adult slaves, 16 horses; $16 in continental securities.68

James Taylor (Caroline), 2,070 acres valued at £2,105; 40 adult slaves, 12 horses, 48 cattle, and one phaeton (1787). An unidentified James Taylor funded $419 in continental securities. Whether it was this delegate, or Dr. James Taylor of Norfolk, or some other James Taylor cannot be ascertained.69

William Thornton (King George), 400 acres valued at £426 14s.; 15 adult slaves, 13 horses; $1,224 in continental securities.70

Walker Tomlin (Richmond), 274 acres valued at £124 8s •; 60 adult slaves, 7 horses, 80 cattle (1786); $499 in continental securities.71

Henry Towles (Lancaster), 485 acres in Lancaster and 1,230 acres in Culpeper, total value £396 7s.; 12 adult slaves, 5 horses, and a carriage.

Isaac Vanmeter (Hardy), landholdings unknown; 9 slaves and 10 horses co-owned with Jacob Vanmeter; $2,385 in continental securities.72

Thomas Walke (Princess Anne), 1,000 acres valued at £425; 18 adult slaves, 15 horses, a two-wheeled carriage, and a stud horse worth £1 10s . for seasonal covering. Walke’s slaves had been confiscated by Lord Carleton during the war, and he had paid off prewar debts by payments into the state treasury.73

Bushrod Washington (Westmoreland), land valued at £1,300; 19 adult slaves, 12 horses, a six-wheeled phaeton, a chair, and a stud horse worth 12 shillings for a season’s covering.

James Webb (Norfolk County), 878 acres valued at £256 1s. (1787); 21 adult slaves, 6 horses, and a two-wheeled carriage.

Worlich Westwood (Elizabeth City), 1¾ town lots with annual rental of £20 and 498 acres valued at £262 6s.; personal property unknown.

John Williams (Shenandoah), one town lot with a £5 yearly rental and 61 acres valued at £28 4s.; 5 adult slaves, 5 horses. Williams was the clerk of the Shenandoah County Court in 1788-1789.

Benjamin Wilson (Randolph), size of estate unknown.

John Wilson (Randolph), size of estate unknown.

John S. Woodcock (Frederick), 500 acres valued at £236 13s.; 7 adult slaves, 11 horses, and a four-wheeled stage coach.

Andrew Woodrow (Hampshire), landholdings unknown; 2 adult slaves, 4 horses; continental securities on which he received $416 interest in 1786.74

Archibald Woods (Ohio), 400 acres valued at £33 6S.; personalty unknown; $519 in state securities.75

ECONOMIC INTERESTS OF DELEGATES VOTING AGAINST RATIFICATION

Four of the anti-Federalist delegates were merchants:

Isaac Coles (Halifax), brother-in-law of Elbridge Gerry, having, like Gerry, married one of the daughters of the New York City merchant James Tompson. Coles owned, in addition to his mercantile property, 1,640 acres of land valued at £702 13s ., 13 adult slaves, and 13 horses.76

Stephen Pankey (Chesterfield), who owned, in Chesterfield, a store, a town lot with yearly rental of £ 160, 1,587 acres of land valued at £ 706 16s ., 6 adult slaves, and 3 horses, and in Powhatan 573 acres valued at £180 4s . Pankey also owned $111 in continental securities.77

Parke Goodall (Hanover), who owned a retail store, an unknown amount of land, 16 adult slaves, 8 horses, and $186 in continental securities.78

Henry Dickenson (Russell), who owned a country store, 150 acres valued at £ 26 17s ., one slave, and 7 horses.

Twelve were lawyers:

Cuthbert Bullitt (Prince William), 527 acres in Prince William and 2,200 acres in Botetourt, total value £398 9s.; 5 adult slaves, 5 horses, and a four-wheeled chair.79

John Dawson (Spotsylvania), 588 acres valued at £271 19s.; 23 adult slaves, 6 horses, and 10 cattle (1787). Dawson and anti-Federalist James Monroe shared a house in Fredericksburg which they rented from anti-Federalist Joseph Jones.

William Grayson (Prince William), 2 town lots, 685 acres valued at £475 4s ., and 7,592 acres of western land received as bounties for military service.80

Patrick Henry (Prince Edward), 8,534 acres in Henry County and 70 acres in Prince Edward County, total value £3,757 19s.; 40 adult slaves, 29 horses, and a two-wheeled coach.

Samuel Hopkins (Mecklenburg), 875 acres valued at £295 6s. and 7,833 acres of Kentucky land received as military bounties; 21 adult slaves, 16 horses, and a chair; $5,133 in continental securities.81

Joseph Jones (Dinwiddie), 2,503 acres valued at £2,189 14s.; 19 adult slaves, 19 horses, and a four-wheeled chariot; $32 in state securities.82

Henry Lee (Bourbon), whose holdings of land and slaves are not ascertainable.83

Stephens Thomson Mason (Loudon), 1,000 acres valued at £758 6s.; 71 slaves, 28 horses, 76 cattle, a four-wheeled chaise, and a stud valued at 18 shillings for a season’s covering (1787); continental securities on which he drew $32 interest in 1788.84

James Monroe (Spotsylvania), no listing of either land or slaves in the county other than the house he rented with Dawson. He owned 5,333 acres of Kentucky land which had been granted to him for military service.85

Abraham Trigg (Montgomery), 155 acres valued at £100; 5 adult slaves, 7 horses.86

John Tyler (Charles City), 569 acres valued at £344 6s. ; slaveholdings not ascertainable.87

Edmund Winston (Campbell), 500 acres valued at £220; 17 adult slaves, 15 horses.88

One of the anti-ratificationist delegates, Theodorick Bland (Prince George), was a physician. Bland owned 1,339 acres valued at £880 14s . and 6,666 acres of Kentucky land received as a bounty for military service; 19 adult slaves, 10 horses, and a four-wheeled carriage; more than $5,000 in state and continental securities.89

One of the anti-ratificationist delegates, Charles Clay (Bedford), was a minister.90

Sixty of the delegates who voted against ratification were planters and farmers:

Robert Alexander (Campbell), 1,742 acres valued at £545 13s.; 10 adult slaves, 21 cattle, and a two-wheeled carriage (1787).

Thomas Allen (Mercer), the size of whose estate is not ascertainable.

Thomas Arthurs (Franklin), 717 acres valued at £337 18s.; 6 adult slaves, 8 horses.

David Bell (Buckingham), 426 acres in Buckingham valued at £111 16s. and 501 acres in Lunenburg valued at £204 14s.; slaveholdings unknown. Edmund Booker (Amelia), 568 acres valued at £305; 16 adult slaves, 5 horses.

John H. Briggs (Sussex), 3,025 acres valued at £995; 4 adult slaves, 5 horses.

Andrew Buchanan (Stafford), one town lot with £50 annual rental, 364 acres in Stafford and 600 acres in Washington, having a total value of £298 19s.; 9 adult slaves, 6 horses, and a four-wheeled carriage.

Samuel Jordan Cabell (Amherst), 1,444 acres in Amherst and 4,400 acres in Buckingham having a total value of £1,597 13s . and 7,833 acres of Kentucky land received as a military bounty; 21 adult slaves, 11 horses, and a four-wheeled phaeton; $4,529 in continental securities.91

William Cabell (Amherst), 17,837 acres valued at £6,596 11s.; 54 adult slaves, 22 horses, a four-wheeled carriage, and two chairs; $209 in continental securities.92

George Carrington (Halifax), 1,974 acres valued at £1,077 6S.; 12 adult slaves, 7 horses; $2,837 in continental and $112 in state securities.93

Thomas Carter (Russell), 400 acres valued at £38 6s.; one slave, 11 horses.

Richard Cary (Warwick), 350 acres valued at £ 186 135.; 24 adult slaves, 12 horses, a two-wheeled chair, and one stud valued at £ 1 for a season’s covering.

Green Clay (Bedford), 690 acres valued at £ 311 5s.; 6 adult slaves, 6 horses.94

Thomas Cooper (Henry), 1,163 acres valued at £702 12s.; 7 adult slaves, 11 horses.

Walter Crockett (Montgomery), 478 acres valued at £140; 3 adult slaves, 9 horses.

Edmund Custis (Accomac), 534 acres valued at £255 18s.; 18 adult slaves, 11 horses; $1,837 in continental securities.95

Thomas H. Drew (Cumberland), 90 acres valued at £ 46 10s. and 4,000 acres of Kentucky land received as a bounty for military service; no slaves; $466 in continental securities.96

Joel Early (Culpeper), 881 acres valued at £474 1s. ; 31 adult slaves, 9 horses.

John Early (Franklin), 615 acres valued at £184 2s. ; 7 adult slaves, 3 horses; continental securities on which he received $45.80 interest in 1786.97

Samuel Edmiston (Washington), 400 acres valued at £98 6s. (1786); 17 adult slaves, 16 horses, and 36 cattle (1785).

Thomas Edmunds (Sussex), 3,804 acres valued at £1,541 8s . and 4,000 acres received as a bounty for military service; 34 adult slaves, 14 horses, and a four-wheeled carriage; $9,190 in state and $50 in continental securities.98

John Evans (Monongalia), landholdings unknown; 2 adult slaves, 6 horses; continental securities on which he received $371 interest in 1787.99

John Fowler (Fayette), landholdings unknown; 10 adult slaves, 2 horses, and 8 cattle (1787); $1,679 in state and $102 in continental securities.100

John Guerrant (Goochland), 636 acres valued at £334 2s. (1789); 15 adult slaves, 12 horses, and a two-wheeled carriage.

Joseph Haden (Fluvanna), 899 acres valued at £294 8s.; 7 adult slaves, 4 horses.

Benjamin Harrison (Charles City), size of estate not ascertained.

Binns Jones (Brunswick), 400 acres valued at £ 171 13s.; 27 adult slaves, 7 horses, and 22 cattle (1787).

John Jones (Brunswick), 901 acres valued at £412 9s.; 45 adult slaves, 18 horses, 44 cattle, a phaeton, and a chair (1787); $1,136 in continental securities.101

Richard Kennon (Mecklenburg), 1,094 acres valued at £1,120 7s . and 5416 acres received as a bounty for military service; 38 adult slaves, 20 horses, a four-wheeled phaeton, and one stud.102

Robert Lawson (Prince Edward), 894 acres valued at £283 2s. and 10,000 acres received as a military bounty; 11 adult slaves, 9 horses, and a coach.103

John Carter Littlepage (Hanover); landholdings not ascertained; 9 adult slaves, 13 horses; $10 in continental securities.104

John Logan (Lincoln), size of estate not ascertained.

John Marr (Henry), 1,034 acres valued at £458; 7 adult slaves, 16 horses, and a four-wheeled carriage.

George Mason (Stafford), whose enormous estate is described on page 72, above.

Joseph Michaux (Cumberland), 995 acres valued at £555 10s.; 26 adult slaves, 8 horses, and 35 cattle (1787).

John Miller (Madison), size of estate not ascertained.

James Montgomery (Washington), 400 acres valued at £98 6s. (1786); 3 adult slaves, 10 horses, and 16 cattle (1785).

Charles Patteson (Buckingham), 1,984 acres valued at £528 2s.; 31 slaves (1790).

Jonathan Patteson (Lunenburg), 300 acres valued at £138 14s.; 5 adult slaves, 4 horses.

Henry Pawling (Lincoln), size of estate not ascertained.

John Pride (Amelia), 440 acres valued at £236 10s.; 23 adult slaves, 10 horses.

Thomas Read (Charlotte), 2,143 acres valued at £1,581 4s.; 29 adult slaves, 16 horses, and a four-wheeled phaeton; $554 in continental securities.105

Samuel Richardson (Fluvanna), 963 acres in Fluvanna and 546½ acres in Goochland, total value £577; 13 adult slaves and 10 horses in Fluvanna and 9 adult slaves and 7 horses in Goochland; $2413 in continental and $435 in state securities.106

Holt Richeson (King William), 1,615 acres valued at £759 7s. (1785 tax return plus additions recorded in returns for 1786 and 1787) and 6,000 acres received as a bounty for military service; 23 adult slaves, 7 horses.107

Thomas Roane (King and Queen), 3,968½ acres in King and Queen and 516 acres in Middlesex, total value £3,676 4s.; 29 adult slaves, 13 horses, a six-wheeled phaeton and a chair.

Alexander Robertson (Mercer), size of estate not ascertained.

Christopher Robertson (Lunenburg), 600 acres valued at £487; 9 adult slaves, 3 horses, and a two-wheeled carriage.

Edmund Ruffin, Jr. (Prince George), 1,582 acres and 4 town lots, total value £1,541 17s.; 24 adult slaves, 14 horses.

William Sampson (Goochland), 375 acres valued at £137 12s.; 10 adult slaves, 6 horses.

Meriwether Smith (Essex), 2½ town lots with an annual rent of £18, 800 acres valued at £1,077 6s.; 61 adult slaves, 8 horses, 60 cattle, and a two-wheeled carriage (1786).

John Steel (Nelson), 3,055 acres awarded as a bounty for military service; $3,905 in continental securities.108

French Strother (Culpeper), 1,110 acres valued at £877 19s . (1789); 23 adult slaves, 18 horses (1790); $191 in continental securities.109

Benjamin Temple (King William), 2,285 acres valued at £1,434 (1785 tax return plus additions as recorded in 1787 tax returns) and 7,555 acres received as a bounty for military service; 36 adult slaves, 11 horses, a phaeton, and a chair.110

John Trigg (Bedford), 363 acres valued at £272; 8 adult slaves, 6 horses, and a two-wheeled carriage.

Thomas Turpin, Jr. (Powhatan), 866 acres valued at £342 15s.; 18 adult slaves, 15 horses, a four-wheeled chaise, and a chair; continental securities on which he received $429.30 interest payments in 1788.111

James Upshaw (Essex), 220 acres in Essex and 2,119 acres in Caroline County, total value £570 1s.; 21 adult slaves, 5 horses, and 20 cattle (1786); $128 in continental securities.112

Matthew Walton (Nelson), the size of whose estate was not ascertained.

Walton owned continental securities on which he received $213 interest payments in 1786.113

William Watkins (Dinwiddie), 1,929 acres valued at £1,063 19s.; 24 adult slaves, 8 horses, and a two-wheeled chair; continental securities on which he received $7 interest in 1786.114

William White (Louisa), 795 acres valued at £289 18s.; 7 adult slaves, 7 horses; $1,828 in state and $1,695 in continental securities.115

Robert Williams (Pittsylvania), 3,866 acres valued at £1,240 6s.; 36 adult slaves, 17 horses; continental securities on which he received $7.56 interest payments in 1786.116

John Wilson (Pittsylvania), 4,891 acres valued at £2,237 11s.; 27 adult slaves, 14 horses, and a four-wheeled stage wagon.

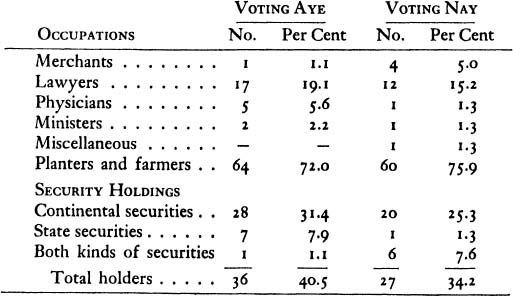

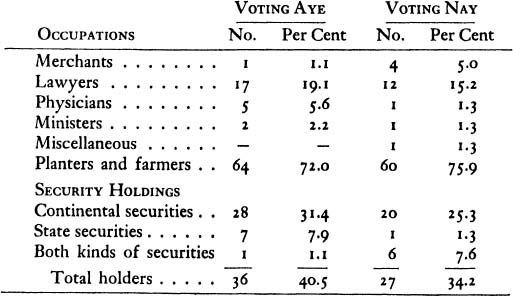

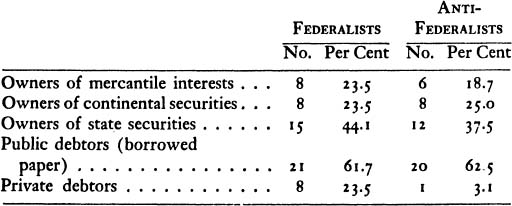

To bring all these sketches to a focus, the following general observations may be made. First, the occupations and security holdings of the delegates may be summarized as follows:

It is clear that with respect to occupations there were no important differences between the delegates who voted for ratification and those who voted against it. The group that favored ratification included a larger number of security holders, it is true, but the margin of difference is not significant.

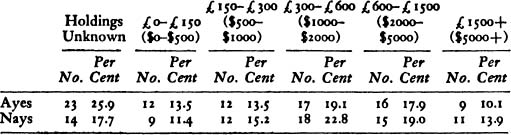

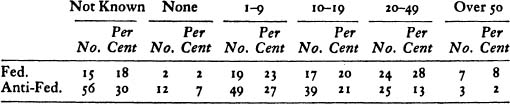

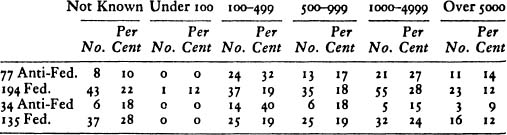

The foregoing sketches reveal that the forms of property most frequently held in significant quantities by delegates, irrespective of occupations or vote on ratification, were land and slaves. The figures for values of lands for tax purposes may or not represent their true value, but for comparative purposes they are valid, since they were arrived at by a uniform system. The values of the landholdings of the delegates voting for and against ratification may be summarized as follows:

It should be pointed out that the great majority of the delegates for whom data on property holdings are unavailable were from areas across the mountains, where land values were low. When this is taken into account, it appears that approximately the same proportions of delegates on the two sides held large and moderate amounts of land, but that the number of small landholders who supported ratification was considerably in excess of the number who opposed it.

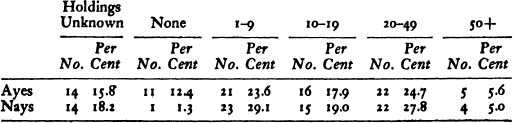

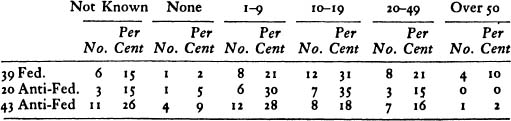

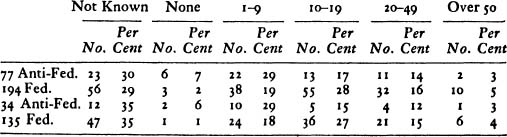

The slaveholdings of the delegates may be summarized as follows:

Significantly, most of the Federalists whose slaveholdings are unknown are those from areas west of the mountains, where slaveholdings were generally small, whereas most of the anti-Federalists whose slaveholdings are unknown were from areas of large plantations.

From the foregoing tables it would appear that planters who had large or moderately large slaveholdings were divided almost equally on the question of ratification, but that the great majority of the small farmers who owned no slaves or very few slaves voted for the Constitution.

Professor Beard interpreted the contest in Virginia on the basis of the geographical distribution of the votes. Largely disregarding the fact that more than a fourth of the delegates were frontier farmers from areas west of the Blue Ridge, he focused his attention primarily on the eastern part of the state. There he found that a substantial majority of the tidewater counties voted for ratification and a sizeable majority of the piedmont counties against it. He ascribed to these areas economic characteristics which close examination would have revealed they did not have, and concluded that most of the support for the Constitution came from wealthy planters and security holders, and most of the opposition from small, slaveless farmers and debtors.

The precise opposite is nearer the truth. Public security holders were almost equally divided and the majority of the small farmers supported ratification. The wealthy planters were almost equally divided on the question of ratification, but planter-debtors, and particularly the planters who had brought about the passage of laws preventing the collection of British debts, favored ratification by a substantial margin.

THE people of the state of New York were overwhelmingly opposed to the Constitution, and the delegates they elected to the state’s ratifying convention were anti-ratificationists by a majority of more than two to one. Only after the convention learned that New Hampshire and Virginia had ratified was their resistance broken. In the face of this news the anti-Federalist delegates decided, at a caucus held on the evening of July 25, 1788, that certain of their number should vote for the Constitution, and on July 26 the document was ratified by a vote of 30 to 27.

New York’s opposition, headed by Governor George Clinton, had begun long before the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 completed its labors. Its delegation to that body voted at the outset against the creation of a general government, and on July 7 they left the Convention. Before the end of July there was in wide circulation a report—originating with Clinton’s political enemy Hamilton but nonetheless valid—that Governor Clinton was busily organizing opposition to any product that might issue from the Convention. In September there began in the Clintonian press a series of attacks on some of the delegates, and repeated newspaper articles gratuitously defending Clinton’s right to oppose the Convention confirmed the talk of Clinton’s opposition.117

A series of articles in opposition to the Constitution was written by Clinton before it was in existence, and on September 27, concurrently with the publication of the document in New York, the first of them, published over the pseudonym “Cato,” made its appearance. A host of wordy arguments on both sides of the issue then began to appear in pamphlets and newspapers. The most celebrated were those appearing in the Independent Journal over the signature “Publius,” later republished as the Federalist Papers. Brilliant though they were, they were smothered by the deluge of anti-Federalist propaganda and were of virtually no influence in deciding votes except in the immediate vicinity of the City.118

New York anti-ratificationists organized powerful machinery not only to work against the Constitution in New York but also to unite anti-Federalists everywhere in a concentrated effort to prevent ratification. For the state campaign clubs named “Federal Republican” or sometimes simply “Republican” were organized in each county; committees of correspondence were appointed and regular meetings held. The central organization had headquarters at the customs house in New York City. It directed the state campaign, served as a clearinghouse for the writing of anti-ratificationist propaganda and for the selection and distribution of the best of it throughout the United States, and corresponded with such anti-Federalist leaders as Grayson, Mason, Richard Henry Lee, and Henry of Virginia, Atherton of New Hampshire, Samuel Chase of Maryland, Rawling Lowndes of South Carolina, Gerry of Massachusetts, Timothy Bloodworth of North Carolina, and others.119

Clinton ignored requests that he call a special session of the legislature in the fall of 1787, and by the time the New York legislature met and got around to calling a convention five states had already ratified. At the end of January, 1788, the House resolved to call a convention after defeating by two votes a proposal to attach to the resolution a preamble censuring the Philadelphia Convention for exceeding its powers. On the same day the Senate concurred in the resolution, also by a two-vote majority. The resolution provided that the convention be held in Poughkeepsie in June and the election of delegates in the third week of April. For these special elections all property qualifications were dropped, and all free adult male citizens were given the right to vote for delegates.120

The elections resulted in a smashing defeat for the Federalists. Anti-ratificationist candidates received more than 14,000 of the known votes as against only 6,500 for the Federalists. Federalists carried only the City and County of New York and three other counties with a total of nineteen delegates; their opponents carried nine counties with a total of forty-six delegates. The popular mandate was clear. It remained to be seen what the politicians would do with it.121

When the convention met on June 17 there was not much, for the moment, that the politicians could do. The Federalists unleashed a brilliant array of debaters, led by Hamilton, Robert R. Livingston, and John Jay. The Clintonians occasionally answered through Melancton Smith, Lansing, and Clinton himself, but more often they followed their customary parliamentary practice of sitting quietly, confident of their voting strength.122 On the present occasion, however, they were uneasy. They were hesitant to reject the Constitution outright, perhaps because they were mindful of the vituperation that had been heaped upon them when they killed the proposed congressional impost early in 1787. They preferred to wait and let some other state be the first to do so.

Eight states had ratified when the New York convention met. The New Hampshire and Virginia conventions were in session at the time, and it appeared likely that one or both of those states might reject the Constitution. When the news of New Hampshire’s ratification reached Poughkeepsie on June 24, the Clintonians were depressed, and when news of Virgina’s ratification came on July 2, their spirit was broken. As late as July 15, however, only five of their number had joined the Federalists.123

The convention approached a stalemate. The Clintonians were divided; one group wanted to reject the Constitution despite the approval of ten states, the other was ready to ratify conditionally, the condition being that New York would automatically retract its ratification unless a second federal convention, to revise the work of the first, were called within a stated period. Hamilton and his allies took advantage of this temporary indecision to employ perhaps the only device that could have succeeded. They solemnly declared that if the convention rejected the Constitution the City and County of New York would secede from the state and join the Union by itself. The announcement was not made on the convention floor, but in repeated private conversations with individual Clintonians. Whether the City would actually have carried out its threat is beside the point; what is important is that the Clintonians became convinced that it would do so. Rumors were printed in the City newspapers that the secession movement was already being organized, and Clintonian delegates were privately pressured at every opportunity.124

The secession rumor having taken effect, the Federalists clearly had the upper hand. The Clintonians made a last vain effort to secure a conditional ratification, but when the Federalists assured them that the new government would not accept such a ratification, they gave up. On July 25 they held the caucus mentioned earlier and decided that some of their number should vote for ratification.125 Apparently the plan was to make the decision rest on a one-vote margin, but one of the Clintonians failed to show up for the vote and Clinton himself, as president of the convention, abstained from voting, so that the final vote was 30 to 27.126

The steps by which both the opposition to and the support for ratification had developed in New York stand out distinctly in the history of the state during and after the Revolution. Before these steps can be traced, however, two sets of facts about the state’s war experience must be understood as the factors that conditioned the atmosphere in New York during the period.

The first is that New York City was occupied by the British from 1776 to 1783. During this long occupation the Whigs in New York came to hate the British and Loyalists with an intensity perhaps unmatched in any other state. The second conditioning factor stemmed from the first. Loyalists in New York were numerous and many of them were wealthy, and the Revolutionary government ordered the confiscation and sale of their estates. The quantity of these sales was enormous, amounting in the Southern District alone (the City and environs) to more than a half million pounds, New York currency ($1,250,000). The opportunities to purchase large parts of these estates for later resale in small tracts set off a wave of speculation that lasted well into the 1790’s. The speculative mania was intensified by an act of 1780 which gave holders of soldiers’ depreciation certificates special purchase rights and made other securities as well as specie legal tender as payment for the confiscated property. Large-scale speculations and manipulations in these securities as well as in land resulted. An atmosphere charged with speculative frenzy conditioned all economic and political activity during the decade following the peace.127

The first step in the development of attitudes toward the Constitution was the rise to power of George Clinton. The prewar struggle between the DeLancey family and allied clans and the Livingston family and its allies culminated with the Declaration of Independence and the framing of a state constitution by the triumphant Livingstonians in 1776-1777. By means of campaign maneuvers among the soldiers Clinton was elected first governor of the state in 1777 in a surprise victory over Philip Schuyler, a higher ranking member of the Whig faction of the colonial aristocracy. Clinton solidified his hold on the government, won the support of much of the aristocracy by his conservative administration, and was re-elected for a succession of three-year terms covering fifteen years. Until the Constitution was ratified Clinton held virtually unchallenged power in the politics of the state.128

At the beginning, and as long as New York City was occupied, Clinton and his followers were strongly pro-Union. The next steps in the shaping of attitudes on the issue of 1788 were those that led New York to a break with its sister states. The first and most important was the termination of the war; when the pressing military need for co-operation ended, New York’s devotion to the Union declined considerably.

The next clear steps were a series of events that engendered distrust and even disgust with the Confederation Congress. The first was the handling of the Vermont question. The Vermont area was claimed by both New York and New Hampshire, and after much wrangling the Congress indicated in mid-1783 that it was disposed to recognize the grants New Hampshire had made in Vermont but that apart from this it was unwilling to take any decisive action on either state’s claims.129

The second and third issues that bred hostility toward Congress were related to the treaty of peace. The Tory-hating, speculating New Yorkers considered that the treaty gave unnecessary benefits to Loyalists, and its ratification aroused in the minds of some New Yorkers the suspicion that Congress was soft on Tories. More important was the weakness shown by Congress in failing to force Britain to abide by the treaty with respect to garrisons inside the United States. Five of the frontier outposts which the British continued to occupy in violation of the treaty were inside the limits of New York. Not only was the maintenance of the posts an insult to New York, but it cut New Yorkers off from a share in the lucrative western fur trade.

In the face of this demonstration of the weakness of Congress, New Yorkers could do one of two things: they could seek a stronger union or they could decide to go it alone. A strong faction in the legislature, consisting almost exclusively of followers of Clinton, was ready by 1784 to pursue the latter course. The complaints with respect to the treaty came to a climax in March, 1784, when both houses resolved to lay an ultimatum before Congress. First declaring that New York was “disposed to preserve the Union” and that it had “an inviolable Respect for Congress,” the legislature gave Congress two months “after nine States shall be represented in Congress, subsequent to this State being represented there” in which to take decisive action regarding New York’s complaints. If Congress failed to respond, the resolution continued, “this State, with whatever deep Regret, will be compelled to consider herself as left to pursue her own Councils, destitute of the Protection of the United States.” 130

Clinton himself was not yet ready to adopt such extreme measures. He acted as an apologist for Congress and sought to discourage the adoption of the resolution. Seven months later, after Congress had resolved in June to do what it could about the British posts, Clinton urged the legislature to accept that as compliance with New York’s ultimatum.131 But when two more elements had entered the picture, Clinton was ready to join his political allies in moving toward a complete break with the Union.

At some time toward the end of 1785 or the beginning of 1786 Clinton began to realize the enormous potential New York had in her natural advantages: a central location, excellent soil, a thrifty and energetic people, a superb system of inland waterways, and a great natural port serving three states, among others. Somewhere along the line, as the City recovered from the war with almost incredible speed, as the entire state underwent an economic boom and tremendous expansion, and as the state collected handsome sums in the form of duties on imports for the tri-state area, George Clinton came to visualize clearly a plan for fulfilling New York’s destiny as the Empire State.

One more step was necessary. Despite his re-election in 1780 and 1783, Clinton was not sure of his political strength. His previous victories had been scored during the war, and the lower counties and the City had not yet had an opportunity to vote in a gubernatorial election. When, in the elections of April, 1786, no candidate could be found to run against him and the legislative candidates he was backing were elected by great majorities, assuring complete control of both houses, this last reservation vanished. The Clintonians were now prepared to “secede” from the Union.132

Two features of the Clintonian program, enacted in 1786-1788, were of primary importance in determining the state’s relations with the Union. One was the state’s rejection of the proposed amendment to the Articles of Confederation which would have given Congress power to levy import duties with which to fund its debts. New York approved the amendment only conditionally in 1786, after the other twelve states had ratified it; and when Congress declared that acceptance of this conditional ratification would invalidate the ratification of several other states, New York rejected the impost plan outright. This action has been described as the “death knell” of the Confederation Congress.133

Of equal importance was the state’s financial program of 1786. Since 1784 there had been agitation in some quarters for an issue of paper money, complaints being rife that the drainage of gold and silver in payment for British manufactures during the last months of the occupation had produced a shortage of specie. The House of Assembly had passed a paper-money measure in 1784 and another in 1785, both of which had been rejected in the Senate. In 1786 the Clinton organization backed the paper issue and combined special features with it to produce an ingenious fiscal scheme.

The plan, all incorporated into a single act, was extremely complex. For present purposes, however, its features may be simplified. Paper money amounting to £200,000, New York currency ($500,000), was to be issued. Of this sum,£150,000 was to be lent to individual borrowers, against mortgages on otherwise debt-free real or personal property amounting to two or three times the amount of the loan. The remainder was to be reserved for funding purposes. The entire state debt was funded and two portions of the national debt were assumed: the continental loan office certificates and the so-called Barber’s notes, certificates issued by the United States for supplies furnished the continental army. Holders of these continental securities were given the right to exchange them, on loan, for state securities of equal par amounts, bearing interest at the same rate. The remaining £50,000 of the paper-money issue was appropriated for immediate interest payments equal to one-fifth of the back interest due from the United States on these securities.134

Continental debts amounting to £557,000 (about $1,395,000) were assumed under this act. The state thus shouldered a heavy burden, but it was relieved of obligation to contribute to any further continental requisitions, for the annual interest now due the state government from Congress amounted to more than New York’s share of the interest on continental debts. The act also furthered the break with Congress in a more subtle way. The continental debt was considered by many in New York to be the strongest, if not indeed the sole remaining bond with the Union. The reason that loan office certificates and Barber’s notes had been chosen for assumption was not, as some charged, that the “honorable members” of the legislature owned only these kinds of debt, but that ownership of these securities was widely spread among at least five thousand holders, a large portion of the voting population. It was, indeed, as one critic charged, “a studied design to divide the interests of the public creditors,” to make their welfare contingent on the state’s welfare instead of the nation’s.135

The program met with opposition only in the City, and it was opposed there not primarily by creditors who feared the money would depreciate—the Pennsylvania paper issue was circulating at or near par, and the South Carolina issue and that of New York were to do likewise—but rather by two special groups for two special reasons.136 In the first place, its anti-Union implications ran counter to the hopes of the advocates of a stronger union, the great majority of whom were in the City. Secondly, the funding-assumption program affected adversely the interests of speculators in confiscated estates. Purchasers of such property had contracted to buy in the expectation that they would be able to pay their obligations in depreciated public securities. The sudden appreciation of security prices as a result of the funding scheme caught many “bears” in a “bull” market, forcing them to pay from thirty to fifty per cent more for their purchases than they had counted on paying. A little panic of 1786 ensued, causing commodity price gyrations and no small number of bankruptcies—an exact precursor of the larger panic of 1792.137

Except for the side effects of the appreciation of securities, however, the program was a complete success. The state government was able to meet its obligations until the United States Loan of 1790 was enacted, and thereafter it literally had more money, in the form of income from the securities it owned, than it knew what to do with. As the state retired its own obligations with the receipts from the sale of confiscated property and public lands and from its impost, more and more of the continental securities “loaned” to the state in 1786 came into its outright ownership. In March, 1790, the state returned the continental securities still outstanding to the original owners, yet Gerard Bancker, as treasurer of the state, was able to fund continental securities amounting to $1,424,041.71 under the Loan of 1790.138

The state was equally successful in other respects. Despite the setbacks caused by the panic of 1786, commercial recovery was rapid. By 1788 New York City, which at the end of the occupation in 1783 had been a broken port virtually without a vessel, was importing and exporting at least three times as much as it had in its best prewar years, and two-thirds of its trade was carried in New York bottoms. Despite the outbreak of Shays’ Rebellion in neighboring Massachusetts, no disorders occurred in New York. Despite the ravages of the Hessian fly, wheat production on New York farms was greater than it had ever been, and prices were at far higher levels than before the war. The Clintonian legislative and administrative program included something for virtually everyone; almost every economic interest and social group was the beneficiary of special legislation. In short, New York’s experiment in independence was eminently successful. The state had little reason to adopt any plan for a general government, for it was prosperous and contented with the government it had.139

The opposition to Clinton consisted of three major groups and an assortment of minor ones, the combined totals of which embraced only a small fraction of the population. One of the major opposition groups was a faction of the aristocracy that had opposed Clinton from the outset. The principal chieftain of these malcontents was Philip Schuyler, whom Clinton had defeated for the governorship in 1777. Schuyler, an otherwise brilliant man, had an almost irrational hatred of Clinton thereafter, and until the day he died he never ceased plotting to subvert his enemy. A man of great influence in the aristocracy, he worked constantly to unify it against Clinton. He never quite succeeded; the powerful Livingston and Van Cortlandt families were split, some supporting and some opposing the governor, and many of the families lower in the aristocracy were Clintonians. But Schuyler was able to weld together a powerful, albeit numerically small, coalition against Clinton.140

Immediately related to the group gathered around Schuyler for personal reasons was the second major group in the opposition. This was a nationalistic group headed by Schuyler’s son-in-law, Alexander Hamilton. By virtue of his marital connection, his persuasive manner, and his financial genius, Hamilton was able to ingratiate himself with various powerful New York merchants and bankers and to unify them in support of his nationalism. Employing his advantages artfully, he managed to split the mercantile clique which had headed the Sons of Liberty. He found ready support among the merchants who were hostile to the Clinton administration because of losses they had suffered as a result of the funding-paper act of 1786. Another group easily brought into the fold were the merchants who owed money to Loyalists, money they had hoped to avoid paying until the Clintonians decreed that such Loyalist credits were the property of the state and that Loyalist debts were obligations of the state. Many merchants and speculators, including John Lamb, Marinus Willett, Melancton Smith, Henry Wyckoff, and the Sands brothers, remained loyal to Clinton. More, however, like Isaac Roosevelt, the Beekmans, the Jays, the Alsops, and the Lows, either drifted into the nationalist camp or were persuaded to come into it by Schuyler or Hamilton.141

A third major element that opposed Clinton was the lesser citizenry of the City, parts of Long Island, and Westchester County. Many of these lesser folk had sided with the Tories during the war, from necessity as well as from inclination. As many more were Whigs who had been trapped behind the lines in 1777 and had no choice but to remain there during the occupation. Tories, Tory-sympathizers, and victims of circumstance were all treated alike in the wave of persecution of Loyalists which Clinton headed after the peace, and few of them were ever inclined to forget or to forgive him. Still another group among the lower ranks in and around the City were the former tenants of Loyalists. The former tenants of James De-Lancey, one of the richest of the Tory landlords, were in a particularly unfortunate situation. The leases of many of them had expired during the war, and in 1780 DeLancey had sold most of his holdings to them. After the war the state had refused to recognize these purchases and the hapless tenants had been forced either to purchase their property a second time or suffer ejection. Other tenants, scarcely more fortunate, were ejected or forced to pay high prices for the properties they occupied when speculators operating on a large scale purchased the confiscated property from the state.142

Hamilton, Schuyler, and their aristocratic and mercantile allies exploited the hostility of these lower classes toward Clinton, and with their backing organized the only important opposition to Clinton’s powerful faction. Only in the City and in Westchester, Richmond (Staten Island), and Kings counties did the anti-Clinton coalition achieve any consistent success, though Albany, Schuyler’s home county, occasionally sent anti-Clintonians to the legislature. Every other county in the state supported Clinton, his measures, and his legislative candidates with majorities ranging from substantial to overwhelming.143

The vote for delegates to the ratifying convention was cast along precisely the lines indicated above. That is, the City and the counties of Kings, Richmond, and Westchester sent Federalist delegates, and every other county anti-Federalist delegates. The majority asked, with Clinton, why should New York throw its great advantages into a common pot? The opposition to the Constitution was based almost entirely upon New Yorkers’ faith in Clinton and his concept of the Empire State.

There were, however, other elements in the City’s vote for ratification. Most, though not all, of the mechanics who had supported Clinton in the 1786 elections voted for ratification. One factor was the campaign appeals of the Federalists to this element. Another was the possibility that under the general government protective tariffs and other legislation designed to promote manufactures would be enacted which would expand the “protected” market for local manufactures from the existing three states to thirteen. This possibility had no appeal to the service industries and the manufacturers who needed no protection, but large numbers of those groups were already hostile to Clinton for the reasons mentioned earlier. Another factor in the vote was the fact that New York City was, for obvious reasons, sensitive about its military vulnerability. Still another was the City’s fear that it would be hazardous to remain outside the Union once a general government for the other states had been framed. The Federalists argued, with telling effect, that discriminatory legislation would be urged by New Jersey and Connecticut congressmen anxious to retaliate against New York for the duties which their states had been forced to pay into New York’s treasury during the 1780’s.