It’s a delightful challenge to include people in our paintings. If not literally the human form, then sometimes the marks of our presence is enough—a discarded fishing lure, an old bridge or a heart with initials carved into a tree, as lovers used to do.

Including the human in one way or another can make nature more accessible, less primal or austere. (Of course, that can be good or bad, depending on your viewpoint.) It can also offer a sense of scale—you’d never know how big some natural objects are without the human form to measure them against.

It’s funny how often fishermen lose their lures, snagging them on unseen obstructions. I’ve found all kinds.

Evidence of human use dating back 10,000 years has been found in Missouri’s Graham Cave, near Interstate 70. It may have provided shelter for an entire village who found the nearby Loutre River a rich source of food—the small human figure gives an idea of scale. I created this sketch with sepia ink.

It took me a full day to notice this heart, carved long ago in the tree by our campsite. Since it was our first camping trip together, I found it rather romantic.

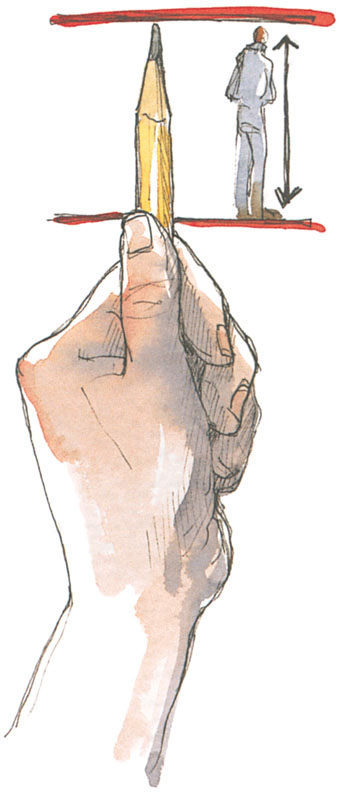

If you have trouble judging the relative size or proportion of the human you want to include in your landscape, take its measure.

Keep it simple! Use any handy tool, like a pencil. Align the tip with your subject’s head, then move your thumb down so it’s on a line with the feet.

Now compare that measurement with others in the scene you’re drawing, still using your thumb and the pencil. How much smaller is the human figure than that rock, tree or whatever? Transfer those proportions to your art.

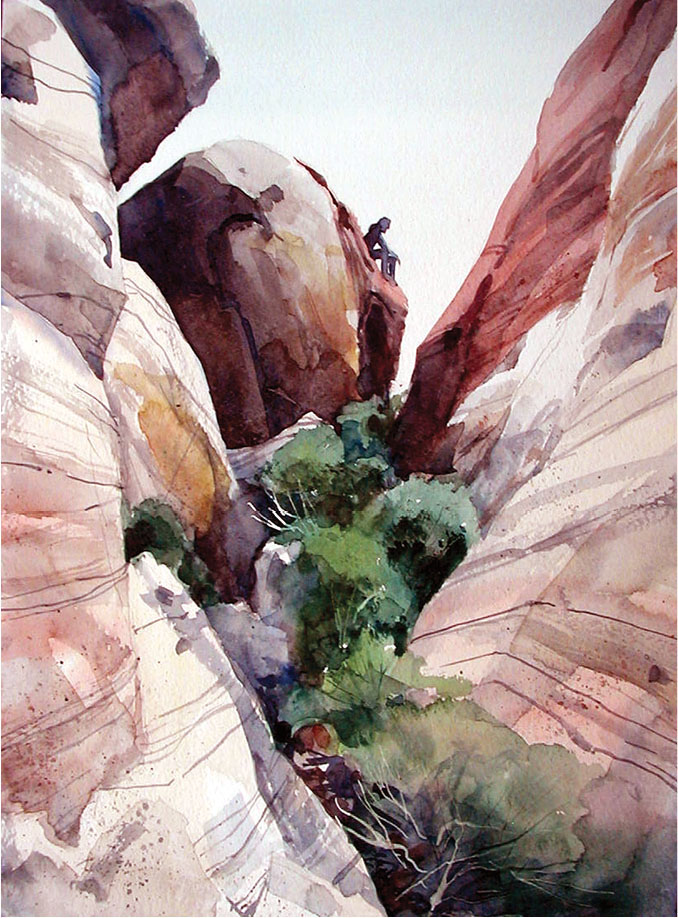

ASCENT

Watercolor on Fabriano cold-pressed watercolor paper

14" × 11" (36cm × 28cm)

Would you realize how huge these boulders are if not for the climber perched high on the distant rocks?