Zero in on the details that define a particular habitat. Field sketches, nature journals, botanical paintings and even wildlife art focus more on the particular than the general. The larger landscape or seascape may or may not play a part in the finished work, in these cases.

Your field sketches can be little more than quick gesture sketches. Lay in a bit of color or not, as you choose. You may prefer to settle in and do a complete painting of the plants or flowers in the vicinity on a white background. You’ll develop a unique relationship with each place.

Perhaps you’ve never noticed the flowers on a weeping willow. When you slow down and pay attention, you discover all kinds of small, perfect details.

Jewelweed pods are fun. When they are fully ripe, they literally explode when you touch them, throwing their seeds in all directions to assure the widest possible distribution. No wonder this plant’s other common name is touch-me-not. A quick, simple sketch like this one, in ink and watercolor, helps capture the sense of motion.

In moist areas, you often see a variety of wildflowers and plants you don’t normally find elsewhere. There may be rich strands of horsetail or equisetum or a bank of colorful jewelweed (illustrated above). Take the time to paint and explore the unique properties of these plants.

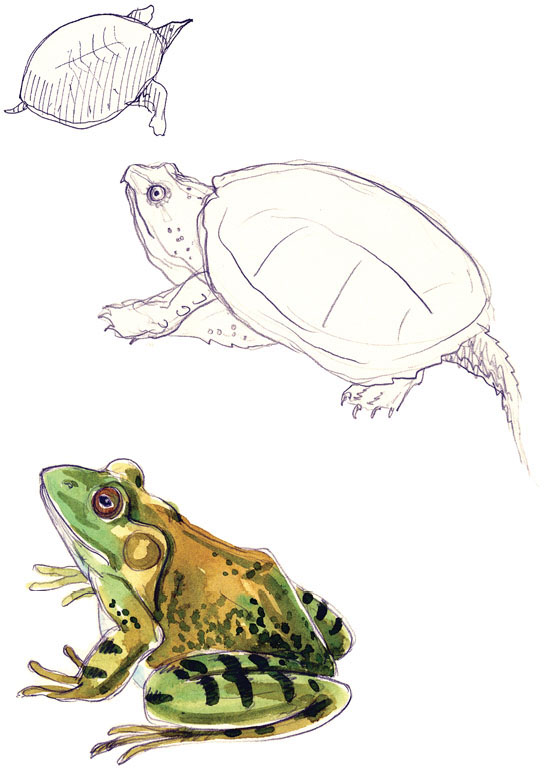

Don’t let a great subject get away because you don’t have “the proper tools.” You can always refine your sketches later. Or, with the help of field guides or photos, you can develop them into more finished works with correct markings and details.

This frog was a lightning-quick sketch in black, wax-based colored pencil, with watercolor washes added later. The turtle at top is a simple ink sketch, and the snapping turtle in the middle is a very quick pencil sketch.

Birds tend to move frequently, so a pencil sketch may be all you have time for. Remember their markings and add them later, or look them up in a book. Don’t feel as though you have to do an illustration worthy of a field guide—you don’t have to paint every feather. Getting their essence down with energy and life is at least as important, if not more so.

I used colored pencils on this red-winged blackbird as well as on the duck. I added watercolor later to suggest their markings.

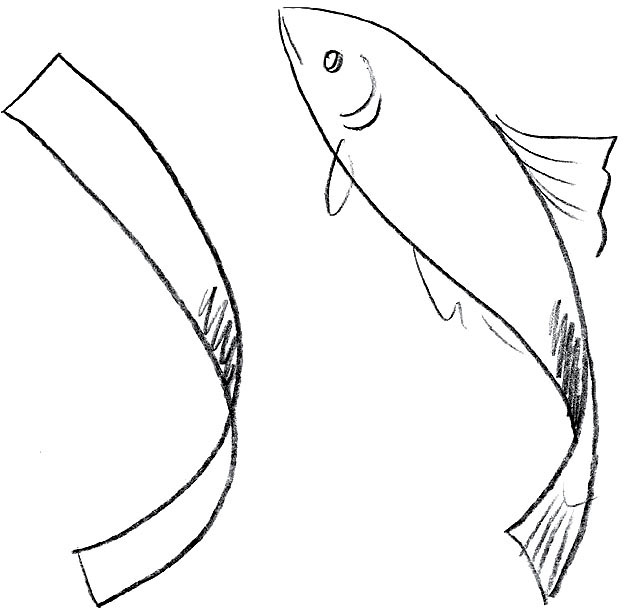

A simple rule of thumb when sketching or painting fish is that they are usually rather flat. That is, they are longer and deeper than they are thick (think of a ribbon shape and flesh it out a bit). The backbone that runs close to the top of the fish defines the motion.

Fish are often very difficult to spot. Usually, you’ll only see the rings in the water where they are rising to feed, or perhaps you’ll spot one as it leaps out of the water. If they are feeding or spawning near the shore where the water is clear, you may get a better look.