neither one thing nor the other

Through a narrow crack in the curtains, I could see the morning coming to life. It was after eight but the sky was still dim, and paled by a haze of snow. From outside I could hear the squeal of metal on tarmac as ploughs roamed the streets, carving smooth trails through the night’s fall. I drew the covers close around me and lay there in bed, listening, until I felt ready for the day.

I rose and showered, then reached into my bag for clothes. I pulled on two T-shirts, two pairs of socks, a pair of thermal long-johns, jeans and a thick, woollen jumper, then my jacket, scarf, hat and gloves. It was a ritual I undertook with anticipatory pleasure, because I like the cold. Not the blustery, biting chill of Shetland, but the calm, still degrees just below zero; the cold that fully fills the air, and necessitates the wearing of ‘sensible clothes’. There is a cleanness to it, and a satisfaction that comes with the knowledge that it can be held at bay. The slap of frozen air against the face; the sharp gasp, deep in the lungs; the sting of pleasure that puckers the skin. It is as sensual and reviving as the thickest of tropical heats, and though I felt well-padded and well-prepared, I was looking forward to that first gulp of frost.

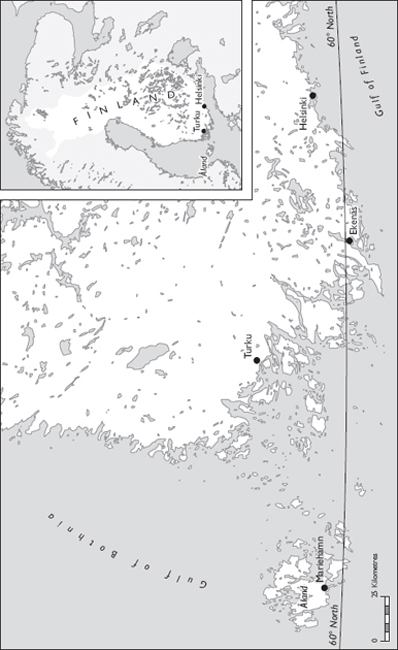

The town of Ekenäs lies at the very tip of Finland, southwest of Helsinki, where the body of the country peters out in a splutter of islets and skerries. In summer it is a tourist resort, offering access to the national park that sprawls across 5,000 hectares of the region’s archipelago. Campers, kayakers, walkers and anglers can all find their fun around these shores. But in winter things are different. In winter it feels like a town waiting for something to happen. At half past nine, as I left the hotel, the light was still tentative, and though the flurries of early morning had ceased, an iron sky was glowering above. After the frantic rush of St Petersburg, Ekenäs was a haven of quiet. The snow muffled and dampened all noise. It gathered and enclosed, covered and concealed. It swaddled the town like the scarves and jackets that swaddled its red-faced pedestrians. Such weather insists on movement, on the necessity of keeping warm by activity, but thick clothing and icy pavements insist otherwise, and make moving difficult. So with heads bowed, the town’s walkers hurried, slowly, in their various directions, breath billowing in the morning air.

As I trudged through the town, there were white piles of clean snow on the verges and brown piles of dirty snow along the kerbs. Winter turns orderly Nordic streets into messy thoroughfares. The pavements were slippery and uneven. Trees, in parks and in gardens, looked ghostly in their white coats. Conifers slouched beneath the frozen burden of their branches.

From somewhere nearby I could hear the ploughs still working their way through the town, mounding up the snow, as they did day after day. It is a Sisyphean task, this constant clearing of the streets. The snow falls and is shifted out of the way. More falls and that is shifted, too. Time and money are swallowed just pushing snow around, from one place to another. The Finns talk of sisu, a kind of stoic perseverance in the face of adversity. It is a stubbornness and a refusal to give in that is considered a personal quality as well as something of a national trait. And perhaps this might be an example of sisu right here: the men in their ploughs each morning and the families clearing drives and pathways with broad-mouthed shovels, then doing it all over again tomorrow. Over and over again tomorrow. Despite its practical necessity, this heroic repetition still feels faintly absurd and overwhelming. But perhaps, as Albert Camus concluded, ‘One must imagine Sisyphus happy’.

Although there has most likely been a settlement in this area since at least the thirteenth century, the town of Ekenäs was officially born in the winter of 1546, by royal decree. At that time, as for much of its history, Finland was under the control of its neighbour to the west, and when the Swedish king, Gustav Vasa, decided to create a new town to compete for trade with Tallinn (then called Reval), Ekenäs was chosen to be that town. Money, materials and men were sent to the region to make the development as swift and effective as possible. And so it grew. But Gustav was not a patient man, and when Ekenäs failed after five years to live up to his expectations, he founded Helsinki a little further north, and concentrated his efforts there instead. Many of this town’s early residents were ordered to relocate to the new settlement, and were not allowed to return until after Gustav’s death.

For centuries, fishing was the main industry here, alongside the export of cattle, timber and animal hides. Craftsmen too began to congregate in the area – tailors, weavers, tanners, cobblers – and in the higgledy-piggledy lanes of the old town, streets still carry the names of the professions they once housed. There is Hattmakaregatan (hat-makers’ street), Smedsgatan (smiths’ street), Linvävaregatan (linen-weavers’ street), Handskmakaregatan (glove-makers’ street). The buildings too are named after the fish and animals that once would have driven the local economy: the eel house, the goat house, the bream, the roach and the herring.

Some mornings, Ekenäs felt stripped out, almost absent from itself, as though in winter the town didn’t fully exist at all. I enjoyed exploring at those times, walking back and forth through the hushed streets, past the same shop windows and the same houses. Sometimes I walked out to the edge of town, where the trees took over, then turned back. I crossed the bridge to the little island of Kråkholmen, then turned again and headed to the Town Hall Square, where the sweet tang of antifreeze rose like cheap perfume from the parked cars.

At night things were quieter still. Parents and grandparents dragged young children on sleds through the town centre, the snow lit like lemon ice beneath the streetlamps’ glow. A few walkers, dog walkers, youths, couples and me: it was peaceful, and pleasant to be out. Only later on was the stillness broken, when boy racers practised handbrake turns at the icy junction outside my hotel, their cars spinning and sliding from one side of the road to the other.

Quietest of all, though, were the narrow streets and lanes of the old town, where footsteps creaked like leather on the trampled snow. Along Linvävaregatan, the oldest section, many of the houses were painted that earthy, Swedish red, with white window panels and features, while on nearby streets the boards were pastel blue, peach, olive and butterscotch. In the garden of one of these houses, a male bullfinch, bright ochre-breasted, seemed almost aware of how perfectly he fitted in this colourful corner. The brightness of the town was completed by strings of Christmas lights slung over windows and trees. Though it was already mid-January, Yule wreaths were displayed on front doors, and electric candle bridges were arched behind glass. In Britain we rush to remove our seasonal decorations, to maintain an arbitrary tradition. Here, though, lights and candles are kept in place. They feel like a natural response to the cold and darkness, not just for Christmas but for the whole winter.

In a narrow lane in the old town, I stood one evening outside the small, square windows of a house. On the vertical weatherboards, the red paint was flaking away, leaving scars of age on the warped wood. Inside, there was no light, but I thought that I could make out two pictures hanging on the far wall: one a painting of a sailing ship, the other of a snowbound landscape. I could see only a few details of the room, but not the room itself. It looked abandoned, as though no one had been in there for years. It was an empty house that held a piece of the past intact. I am not sure what prompted me to want to take a photograph of this window. Perhaps it was the incompleteness of it, and the suggestion that, somehow, what lay beyond the glass was not entirely of the present. I wondered, maybe, if the lens might capture what I could not see, if it might illuminate the fragments and make them whole. But as I lifted the camera from my bag there was a movement inside, a shadow that crossed the space between me and those paintings. It looked like a person shuffling past in the darkness. I jumped back, as though I’d been caught doing something terrible, then turned and walked on, feeling guilty and unsettled. As the moments passed I found myself uncertain about what exactly I’d seen. Had there been a person there or had I only imagined it? I still can’t say for certain.

![]()

Until the twentieth century, Finland had never existed as a nation, only as a culturally distinct region under the control of one or other of its powerful neighbours. Sweden occupied the territory from the mid-twelfth century up until the beginning of the nineteenth, but after the Napoleonic wars it was ceded to Russia, and became a semi-autonomous ‘grand duchy’. In the century that followed, a cultural and political nationalism began to grow in the population. Although the Finnish parliament opened its doors in 1905 (and was the first in Europe to offer universal suffrage), it was not until more than a decade later that the country truly became a country. In the wake of the Russian revolution, Finland declared independence in December 1917, and despite the violence it had suffered at Russian hands in the past, it did not, in the end, have to fight for that independence. Lenin, who had spent time in hiding here from the tsarist authorities back in St Petersburg, was a supporter of Finnish nationalism, and one of his earliest acts as leader was to let the grand duchy go. Had his own history been a little different, the history of this country might also have been so. Though a short, bloody civil war ensued, between those who wished to emulate the new Russian socialism and those in favour of a monarchy, the country ultimately settled on neither, becoming instead an independent democratic republic.

Finland is often described as a strange place, one of the most culturally alien of European states, and in a sense that fact is remarkable. For despite being dominated from outside until just a century ago, this country always maintained an identity that was very much its own. That identity, and that very real sense of difference, was founded first of all upon linguistics. Contrary to a common misrepresentation, Finland is not a Scandinavian country, and its language is entirely unrelated either to those of its Nordic neighbours or to Russian. In fact, Finnish is not an Indo-European language at all. It is Uralic, and related therefore to Estonian and, more distantly, to Hungarian and Sami. However, this cultural odd-one-outness is complicated by the fact that, in parts of Finland, Swedish still predominates, with around five per cent of the population using it as their first language. This southwest region is one of those parts. Ekenäs is a Swedish town, and its Finnish name – Tammisaari – is far less commonly used by its residents. In cafés here, both languages rise from the tables, and nearly every sign, label and menu is printed both in Finnish and Swedish. This biculturalism is different from that of Greenland. For though they once would have been, these are no longer the dual languages of coloniser and colonised. These are two cultures existing side by side, complementary rather than competing. And the difference between the two is not one of national allegiance, either. Swedish speakers in Ekenäs do not consider themselves to be Swedes living in Finland but, rather, Swedish-speaking Finns. To me this seems a refreshing contrast to the simplistic vision of a national identity that is ethnically and culturally defined. It is an acknowledgement that identity – even linguistic identity – is always complicated. But of course, not everyone agrees.

In the centre of town, a row of boards displayed campaign posters for each of the eight presidential candidates in the forthcoming elections. These candidates included a representative of the Swedish People’s Party, which fights to protect the interests of Swedish speakers, and also a candidate from the True Finns, a nationalist group hostile both to immigrants and to the Swedish minority. Supporters of the True Finns resent the continuing use of Swedish as an official second language, and its compulsory teaching in schools. They thrive on a lingering bitterness over the country’s historical mistreatment by its neighbour. On a Friday night during my stay, in an act of quiet political sabotage, one of the True Finns’ posters was removed from its board, and the face of their leader, Timo Soini, was torn from the other, leaving a blank hole that drew laughs of approval from shoppers the following morning. Though replacement posters had been put up by Saturday evening, those did not make it through the night unscathed either. Once again Soini’s face was removed from one, while on the other a neat Hitler moustache was added. In a place as clean and graffiti-free as this, such vandalism was notable. Ekenäs clearly was not natural territory for the party.

In most nations, urban, literate culture has traditionally been valued more highly than rural or peasant culture, and Finland was once no different. But here, up until the nineteenth century, the culture of the town was Swedish, while the culture of the countryside was not. Finns were largely excluded from urban, economic life, and theirs for the most part was an oral culture, a culture of the home, the fields and the forest. After the annexation by Russia in 1809, however, things began to change. For the first time there was a sense that this rural culture could become a national one, and since they were keen to minimise Swedish influence in the territory, the Russians did nothing to discourage this new nationalism. And so, gradually, it grew.

Key to the rise of a rural, national, Finnish culture was the publication in the middle of the nineteenth century of a work of epic poetry called The Kalevala. This huge book, consisting of almost 23,000 lines, was based on the oral verse of the Karelia region, and was collected, collated and expanded by Elias Lönnrot, a doctor, who began his schooling in Ekenäs in 1814. Lönnrot brought together creation myths and heroic tales in a work of folklore and of literature. It was a deliberate attempt to set down a national narrative, comparable to the Icelandic sagas and Homeric epics. And though The Kalevala is less famous internationally than those predecessors, there is no doubt that within his own country Lönnrot succeeded. The book had an extraordinary influence, politically and culturally, and continues to do so even now. A national day of celebration, Kalevala Day, is held each 28th of February.

The oral poetry of Finland persisted into the nineteenth century not despite the fact that it was a suppressed language but because of it. The verses Lönnrot gathered were a kind of treasure that had been kept safe from harm in homes and villages across the region. And likewise, the survival of Finnish as a language and as a culture was possible precisely because its rural heartland was separate from the urban heartland of Swedish. The result of this geographical divergence was that, as a national culture came to be imagined and created, it was the countryside that was at its core. It was the landscape of Finland – the forests, lakes and islands – that shaped the nation’s art, its music and its literature.

Though his first language was Swedish, Jean Sibelius was a fervent Finnish nationalist, and throughout his career he produced work directly inspired by The Kalevala. But it was nature that provided the energy and imagery that moved him most of all. It was that ‘coming to life’, he wrote, ‘whose essence shall pervade everything I compose’. While working on his Fifth Symphony – the last movement of which was the only music to be heard in Glenn Gould’s The Idea of North – Sibelius wrote that its adagio would be that of ‘earth, worms and heartache’. And seeing swans fly overhead one day he found the key to that symphony’s finale: ‘Their call the same woodwind type as that of cranes, but without tremolo,’ he wrote. ‘The swan-call closer to trumpet … A low refrain reminiscent of a small child crying. Nature’s Mysticism and Life’s Angst! … Legato in the trumpets!’ Gould, hearing this music in his native Canada, recognised something distinctively northern about it, something that chimed with the themes he wished to explore. It was, he said, ‘the ideal backdrop for the transcendental regularity of isolation’.

![]()

On the broad pier down at the north harbour, summer restaurants stood abandoned, their outside tables, chairs and umbrellas deformed beneath six inches of snow. On one side of the pier, behind a tall metal gate, was a jetty that housed two public saunas, one for men and one for women. To the right of the jetty were the saunas themselves, and to the left was a square of sea enclosed between three platforms. Half of this square was covered by ice, like the rest of the harbour (the Baltic’s low salinity means that it freezes more easily than most seas). But a patch beside the boardwalk was kept clear by a strong pump bubbling from below. Those few metres of ice-free water were the swimming pool.

I have swum in the sea in Shetland on many occasions, though mostly when I was young and stupid. That was cold. It was always cold, even on the warmest day. The Gulf Stream may keep the North Atlantic milder than it might otherwise be, but knee-deep in the waves, goose-pimpled and shivering, you would be hard-pressed to notice. But the difference between that cold and the cold of Ekenäs harbour was probably several degrees. And though I’d come to experience the sauna for myself, the idea of plunging into that ice-edged water, either before or after the heat, did not fill me with excitement. It was an experience that could surely be pleasurable only in hindsight: as something I had done, not as something I was about to do. And certainly not something I was in the process of doing.

The swimming, I’d been told, was optional, which was a relief. But beyond that, I really didn’t know what I was supposed to do. There must be rules and protocols for a sauna, I thought. There are always rules and protocols for such culturally significant activities. I had assumed there would be other people whose lead I could follow, to avoid any serious lapses in social etiquette. But the only other guest was just leaving the changing room as I arrived, and so I was on my own. I’d read somewhere that most saunas do not permit the wearing of trunks, and so I’d not brought any. In fact, trunks had been pretty low on my list of things to pack for Finland in January, so I had none to wear even if I’d wanted to. Public nakedness is not something I have engaged in often, but in this case I was willing to do as is done, and so I stripped, opened the door to the shower room, and then went in to the sauna.

The room itself was just two metres deep and about the same wide, with wood panelling all over, and three slatted steps rising up from the entranceway. There were two windows on one side, and a metal heater was in the corner beside the door. On the top step, where I gingerly sat down, was a pail with an inch or two of water and a wooden ladle inside. I scooped a spoonful out and flung it onto the hot rocks. The stove screamed in protest. The temperature rose quickly in response, and steam curdled the air. An unfamiliar smell, sweet and tangy, filled the room: the smell of hot wood oils.

I sat back against the wall and looked out of the windows at the ice-covered sea. I was sweating from every pore, and my breath felt laboured on account of the steam. It was relaxing, but not entirely. One could rest, but not sleep. Again I wished for guidance: how long was I supposed to stay in the sauna? Was there something else I ought to be doing, other than just sitting? Was now the moment I should be throwing myself into the sea? I could hear people next door, in the women’s sauna – there was laughter, and even the occasional shriek – but I could hardly pop in to ask for their advice. So instead I compromised and took a cold shower. It seemed suitable and not too cowardly an option. Open-mouthed and shaking hard, I stood beneath the flow of water for a moment that felt like an hour, my whole body trying to resist the ache of it. Then I rushed back into the sauna again, sweat bristling on my wet skin.

This ritual of intense heat and intense cold is considered a bringer of health, good for both mind and body. It has been part of the culture of this region for over a thousand years, and its importance is perhaps reflected in the fact that sauna is the only Finnish word to have found its way into common English usage. Today most Finns have one in their home, and many enjoy them at their workplace too. People socialise here; they have business meetings; and sometimes they just come to sit alone.

A sauna is an ideal place in which to be omissa oloissaan, or undisturbed in one’s thoughts. Quiet contemplation is something of a national pastime here, instilled from childhood. ‘One has to discover everything for oneself,’ says Too-ticky, in Tove Jansson’s Moominland Midwinter, ‘and get over it all alone.’ Silence and introspection are not just socially acceptable in Finland, they are considered positive and healthy. They are traits often misinterpreted by those from more talkative cultures as shyness or even bad manners.

Saunas mimic the Nordic climate – the heat of summer contrasted with the cold of winter – and when enjoyed at this time of year they hint at a kind of defiance or protest. To step into a little wooden room at eighty degrees celsius is to declare that even now, in darkest winter, we can be not just warm but roasting hot. We can make the sweat drip from our brows, then leap like maniacs into icy water. It is both an embrace of the season and a fist shaken in its face. It is a celebration of the north and an escape from its realities. The actress and writer Lady Constance Malleson went further. For her the sauna was ‘an apotheosis of all experience: Purgatory and paradise; earth and fire; fire and water; sin and forgiveness.’ It is also a great leveller, and appeals therefore to the spirit of Nordic egalitarianism. ‘All men are created equal,’ goes an old saying. ‘But nowhere more so than in the sauna.’

After repeating this dash from cold shower to hot room twice more, I decided that I’d had enough. It was strangely exhausting, and I felt the need, then, to lie down. As I stood drying and dressing in the changing room, two men came in. They were in their sixties – one perhaps a little older. Both stripped down to trunks quickly, opened the door without a hesitation and went outside. I heard them splash into the sea, and a moment later they returned, dripping but not shivering, took their trunks off and went past me into the steam and heat next door. For a moment I considered turning round and joining them, as though I could shed my awkwardness by sharing others’ ease. But I decided not to intrude on the silence of friends, and so I headed back out into the cold.

![]()

From the centre of town I trudged ankle-deep down the tree-lined streets until, at the end of Östra Strandgatan, the trees took over. A woman and her little dog went ahead of me into the forest and I followed, treading carefully down the path. When she stopped to allow a procession of school-children to pet the dog I overtook and continued beneath the branches, their giggles and chatter rippling into silence behind me. This was the first of the town’s nature parks – Hagen – with the islands of Ramsholmen and Högholmen, accessible by footbridge, lying beyond. The forest was mostly deciduous, so bare of leaves, but a map in my pocket identified some of the species: oak, wych elm, common hazel, horse chestnut, small-leaved lime, black alder, common ash, rowan, bird cherry. Away from the old town, with its colourful buildings, this place seemed altogether monochrome. Dark trunks against the white ground, beneath a bruised, grey sky. Even the birds – magpies, hooded crows and a flock of noisy jackdaws – added no colour.

I walked along the trail, through Hagen, then Ramsholmen, without purpose or hurry. The path was well maintained and trodden, though I could neither see nor hear anyone else around me. As I moved further from the town, the only sounds remaining were the patter and thud of snow clumps falling from branches to the ground, and the occasional bluster of birds somewhere above. Despite the absence of leaves, the canopy was dense enough to make it hard to see much at all, just now and then a flash of frozen sea emerging to my right. When I crossed the second footbridge, to Högholmen, the path faded, but still the snow was compacted by the footprints of previous walkers, and I continued to the island’s end, where I could look out across the grey ice to the archipelago beyond.

In Finland, familiarity with nature is not just approved of, it is positively encouraged, and the state itself takes an active role in this encouragement. The path on which I had walked was well tended, despite the season, and street-lights had continued for much of the way, so even darkness couldn’t interfere with a stroll in the forest. There were bird boxes everywhere, and benches, too, where one could stop and think and rest. The right to roam is enshrined in law in this country, as it is in the other Nordic nations. It is called, here, ‘Everyman’s right’, and gives permission for any person to walk, ski, cycle, swim or camp on private land, no matter who owns it. Food such as berries and mushrooms can be gathered on that land, and boating and fishing are also allowed. The restriction of these rights by landowners is strictly prohibited. Indeed, the legal emphasis is not on the public to respect the sanctity of ownership, but on those with land to respect other people’s right to use it. This means that, while land can still be bought and sold, it is a limited and non-exclusive kind of possession. The public, always, maintains a sense of ownership and of connection to places around them.

The emphasis on access and on the importance of the countryside in Finnish culture harks back to the rural nationalism of the nineteenth century. But it has become, in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, a deep attachment to nature that finds its most notable expression in the profusion of summer-houses dotted around this country. Around a quarter of Finnish families own a second home or a cottage outside the town, and most have regular access to one. Often these are located on an island or beside a lake, and while many have no electricity or running water, nearly all are equipped with a sauna. This region alone has about five thousand of these cottages.

There is an old stereotype that says Finnish people, given the choice, will live as far apart from one another as possible, and perhaps there is a grain of truth in that. Perhaps the desire to remain close to nature necessitates a certain geographical distance from one’s neighbours. But there seems to me something extraordinarily healthy in the attachment to place that is so prevalent here. There seems, moreover, something quite remarkable in this longing not for what is elsewhere but for what is nearby. It is an uncommon kind of placefulness that is surely the opposite of isolation.

On my way back towards town I stopped on the bridge between Högholmen and Ramsholmen. I took ham and rolls out of my bag and put together some crude sandwiches. I stamped my feet on the wooden planks to try and compensate for my gloveless state. As I stood eating, an old man in a bright green coat appeared from behind me. He must have been close by during my walk around Högholmen, though I never saw nor heard him once.

The man stopped beside me and gazed out over the frozen water. His face was soft and wrinkled, and a little sad, topped by grey, sagging eyebrows. His dark-rimmed spectacles seemed to hang precariously at the end of his nose, and yet, at the same time, they pinched his nostrils so tightly that his breathing must have been restricted.

‘I’ve been looking for an eagle,’ he said.

‘A sea eagle?’ I asked.

‘Yes, a big one.’ He extended his arms and flapped slowly, in demonstration of what a big sea eagle might look like in flight.

‘I didn’t see it today,’ he explained, solemnly. ‘But some days it is here.’

We stood together in silence for a moment, both looking in the same direction.

‘Well,’ he said, glancing up at the sky, ‘it is fine now. But for how long?’

I smiled and nodded, recognising both subject and sentiment.

‘What is coming tomorrow?’ he added, turning away to go, then paused a second longer and shook his head, sadly. ‘I don’t know.’

Returning to Shetland from Prague in my mid-twenties was not the joyous homecoming I might quietly have hoped that it would be. It was difficult and tentative, and for a short time I questioned whether my decision had been sound at all. By then, my mother had moved away from Lerwick and away from the house in which I’d spent my teenage years, the house overlooking the harbour. Much had changed since then, and much was new to me. I had returned to Shetland because, finally, it had come to feel like home, but in those first few months a great deal again was unfamiliar.

Not long after coming back I got a job as a reporter for The Shetland Times, and a little flat in Lerwick, a few lanes away from where I’d been brought up. I settled in to a life that I felt I had chosen, and, as I walked through the town again, those buildings and those streets, those lines and those spaces, seemed as though they were etched inside of me.

In the months that followed I began to write every day, more than I had ever written before. I started work on what I thought was a novel: the story of a man’s return to the islands after many years away. In that story, the man – I never chose a name for the character, he was simply ‘the man’ – reconnected himself with his home by walking, obsessively, the places he once knew. The steps he took not only rejoined him to the place, physically, they also drew him back, through his own history and into the history of the islands themselves. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that, through his physical connection, he drew the past upwards into the present. To fuel this work, I read books about Shetland history. I read novels and poetry. I visited the archives and the museum, and I learned much that I had never before been interested in learning. Through that anonymous character, I strove to relate myself to a place from which, previously, I had always maintained a distance.

It was then, in that time of research and writing, that I realised something which now seems obvious: that this history in which I was immersing myself was not separate from me. These islands’ history could be my own. Though I had no connection by blood to Shetland, though my ancestors so far as I know had nothing whatsoever to do with the place, none of that truly mattered. The ancestors of whom I am aware lived in Norfolk and Cornwall and Ireland, places I know hardly at all. My connection to those places, carried in fragments of DNA, has little real meaning. Certainly it means nothing when compared to the connections I have made in my own lifetime. For culture and history are not carried in the blood. Nor is identity. These things are not inherited, they exist only through acquaintance and familiarity. They exist in attachment.

As I came to understand that fact, a sense of relief washed over me like a slow sigh, and I began to imagine that a matter had been settled and that something broken was on its way towards repair. By day, as a reporter, I wrote about Shetland’s present; by night I read and wrote about its past. As familiarity and acquaintance grew, attachment brimmed within me.

![]()

In Turku, the country’s second city, I boarded one of the enormous ferries that ply back and forth between Finland, Sweden and the Åland Islands. In the terminal, crowds had gathered in advance of departure time, laughing, talking cheerfully to each other, and once on board they filed into cafés, restaurants and – most popular of all – the duty-free shop. Soon, the ship was full of people, most of them weighed down by bags of alcohol and cigarettes.

Åland is separated from mainland Finland by a stretch of the Baltic that never fully unleashes itself from the land. From Turku we passed densely forested islands with bright summer houses at the shore. And though, as the morning progressed, the islands thinned out and decreased in size until an almost open sea stretched out around us, here still were holms and islets, some as smooth and subtle as whales’ backs, just breaking the surface. From the boat, these islands looked as though they had just risen up from beneath the water – which in fact many have. The land here is rising at fifty centimetres per century, so new islands are emerging all the time. And when they do so, it doesn’t take long before they are occupied by trees. Even the smallest of skerries, it seemed, had at least one rising from it. Coming from a place where such extravagant vegetation needs to be coaxed and coddled from the ground, it was amazing to see this profusion. In the Baltic, trees won’t take no for an answer.

The sixtieth parallel runs through the south of the Åland archipelago, not far from the capital, Mariehamn, where we docked around lunchtime. Disembarking, with rucksack slung over my shoulder, I was surprised to see most of my fellow passengers walk out from the ferry and then straight back on to another one heading in the opposite direction. For the majority, it turns out, the journey is simply the first half of a full day’s cruise to Åland and back, with good food and tax-free shopping more important than the destination. I stepped out into the town’s grey winter light and headed for my hotel.

If there is ambiguity in the relationship between Swedish Finns and the state in which they live, in Åland the situation is rather different. Here, there is less ambiguity and more complexity. These islands belong, officially, to Finland, but they are culturally Swedish and politically autonomous. The residents are highly independent-minded. The archipelago has its own parliament, its own bank, its own flag and its own unique system of government. Despite a population of fewer than 30,000, spread over 65 inhabited islands, Åland has the power to legislate on areas such as education, health care, the environment, policing, transport and communications. It is, to all extents and purposes, a tiny state operating within a larger one, and its separation from that larger state is fiercely maintained. Finnish is not an official language in these islands, and the army of Finland is not welcome on its shores.

This strange situation did not come about because of a long-held sense of nationhood here (unlike, say, in the Faroe Islands). Instead, it was the result of a peculiar and, in hindsight, rather enlightened decision by the League of Nations. For centuries these islands had been a de facto part of Sweden, but in 1809 they were annexed together with Finland. Åland became, then, part of the grand duchy that survived until the revolution of 1917. At that time, as Finland prepared to announce its own independence, Ålanders demanded that the islands should be returned to Sweden, both for reasons of cultural continuity and to be brought under the protection of an established and stable state. But given the history of this region, the request was not a simple one to grant, and when the three sides failed to agree, the matter was referred instead to the League of Nations. In attempting to come up with a solution that would please everyone, the League settled on a compromise. Rather than staying with one state or joining another, Åland would instead become autonomous and demilitarised. It would function within the state of Finland, but its Swedishness would be enshrined in law. It would be, in other words, neither one thing nor the other. Such a precarious compromise could easily have been a disaster, but in this case it was not. In fact, it turned out remarkably well. Today islanders are proud of their autonomy and what they have done with it. They maintain strong links with both neighbours, but have fostered and cultivated a sense of distinctiveness and independence that is now, almost a century later, firmly embedded.

Mariehamn sits on a long peninsula, with a deep harbour on one side where the ferries come in and a shallow one on the other, for pleasure craft. In the smaller harbour, expensive boats were hidden beneath plastic wrappers, while the wharf was chock-a-block with empty spaces, to be filled by summer visitors.

I strolled across the bridge to Lilla Holmen, a snowy, wooded park that was more or less empty of people. An aviary stood among the trees there, teeming with zebra finches, budgerigars, parrots and love birds, and there was even a tortoise, lying still in the corner. Outside in the park were giant rabbits in hutches, and three peacocks that approached me, then raised and shook their fans as though in protest.

There is an unmistakable air of self-confidence to Mariehamn. The town feels like what it almost is: the capital of a tiny Nordic nation. The wide linden-lined boulevards; the grand clapboard villas; the lively, pedestrianised streets: Mariehamn pulses with a kind of energy that belies its scale. Just 11,000 people live in this town, and yet it seems many times bigger. It feels creative and vibrant and prosperous. In the summer this place would be full of visitors – Finns and Scandinavians, mostly – but in January there were few of us around. Yet unlike in Ekenäs, that didn’t feel like a loss. There was no sense of limbo, or of absence. Tourists bring money to the islands, but they don’t bring purpose. Åland’s focus is upon itself and its own concerns. After all, how many other communities of 28,000 can boast two daily newspapers, two commercial radio stations and one public service broadcaster?

I couldn’t help comparing this place with home, and with Shetland’s own capital, Lerwick. As I wandered Mariehamn’s rather grand streets I thought of the streets in which I grew up. In the time I’ve known it, my home town has changed significantly, and despite the islands’ wealth it has begun to look a little run down. An enormous supermarket on the edge of town has sucked much of the life from its centre. Once home to a host of independent businesses, the town’s main shopping street is now a place of hairdressers and charity shops, and Lerwick’s museum and its recently-built arts centre are outstanding in part because of what they are set against.

I wondered then, as I have often wondered, whether more autonomy could have brought some of the benefits to Shetland that Åland has seen, and I think perhaps it could. But Åland’s success has been bolstered by two factors that are not on Shetland’s side: geography and climate. These islands are not just beautiful, they are also sunny and warm in summer, and therefore very popular with tourists. Åland is also fortunate to lie halfway between two wealthy countries, and a tax agreement means that Finns and Swedes can take day cruises here and come home with bags full of cheap booze. Åland is politically autonomous, but it is still financially reliant on its neighbours. In the 1930s, the largest fleet of sailing ships in the world was owned by the Åland businessman Gustaf Erikson, and the economy is still very much dependent on the sea. The ferries which today carry around a million passengers each year back and forth across the Gulf of Bothnia are, by a considerable margin, these islands’ biggest industry.

![]()

Wandering on a half-faded afternoon, I stepped on impulse in to the Åland Emigrants Institute, which occupies an unassuming building set back from Norre Esplanadgaten, one of the main streets in the centre of town. I’d read somewhere that there was an exhibition inside, but the institute is not a promising looking place and it wasn’t clear if visitors were actually welcome. Inside there was little to indicate whether I was in the right place at all, just a narrow hallway and corridor with an office at the far end, its door open. I turned to go again, disappointed, but was stopped as I did so by a woman beckoning me back. ‘It’s not really an exhibition,’ she said, in answer to my question. ‘It’s just a few things. But do come in anyway.’

The office was cramped. Inside were two large desks facing each other, with books and files and folders stacked everywhere around the room. The exhibition, as warned, consisted of a few odds and ends – some old photographs, crockery and medals – but I wasn’t really shown any of it. Instead I was sat down, offered a cup of tea, then bombarded with questions.

The woman who had shown me in was Eva Meyer, the director of the institute, and her colleague at the other desk was Maria Jarlsdotter Enckell, a researcher. Eva was middle-aged, quiet and attentive; Maria was in her seventies, with well-tended white hair, and a pair of glasses clutched in her hands. As I sipped at my tea, the two women asked about my travels. Where was I from? Where had I been? Where was I going next? Why was I doing it? We spoke about the sixtieth parallel, and about the countries through which it passed. They liked the idea of my journey, they told me; they liked the connections that it made. Eva took a globe from the corner of the room and returned to her desk, turning it slowly as we spoke, her finger following the line. Both women had been to Alaska recently, they said, to attend a conference about Russian America. I told them about my own time there, and about the village of Ninilchik, with its little Orthodox church. Eva and Maria looked at each other, their eyes widening. ‘Ninilchik? Really?’ they asked. I nodded and waited for an explanation.

I had arrived at the institute at 3.30 p.m., half an hour before it was supposed to close. But at four o’clock Maria and Eva were only just beginning their story. The place of Finns in Russian history, they told me, had been vastly underestimated, particularly in terms of its colonial expansion. After all, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Russia was still struggling to man its overseas developments. St Petersburg was only a hundred years old, and the country simply didn’t have enough trained and experienced seamen. Residents of the grand duchy, with its longer maritime history, were extremely useful and often were willing recruits. The Russian American Company offered Finns the security of a seven-year contract in Alaska, with as much salmon as they could eat, as well as an annual salary and accommodation. By signing on as mariners, or with other trades and skills, the men would have a chance to climb in society, working their way up from cabin boy to skipper.

Maria told me the story of one such recruit, Jacob Johan Knagg, who was born at Fagervik, close to Ekenäs, in 1796. By the time he came of age, Finland was under Russian control, and with his mother dead and his father remarried, Knagg decided to go abroad. He left Finland first for Estonia, on a trading ship owned by the local ironworks, but at some stage – probably around the end of the 1820s – he must have joined the Russian American Company.

In 1842, Knagg was working on a cattle farm on Kodiak Island along with his wife, whom he probably met in Alaska. Six years later he applied for colonial citizenship – an application that was ultimately successful. By that time, he was reaching retirement age, and as was customary he was discharged with enough food to last for a year, plus the equipment and supplies he would need to build a home. The Knagg family were then sent to the newest Russian settlement in Alaska. Which is where, in the summer of 1851, Jacob Johan Knagg died, leaving behind his wife and seven children. That settlement was Ninilchik.

Every so often, Eva or Maria would search for something to help illustrate the story. They brought out files, lists of names and family trees. According to Maria, as many as a third of ‘Russians’ in Alaska were not Russian at all; they were Finns, Estonians, Latvians, Danes and Poles. There was a deliberate attempt, she said, to minimise and even deny this fact, because it didn’t fit with Russia’s official, patriotic story. Historians in North America too were reluctant to accept her research, Maria explained. They had, she told me, been ‘blinded by politics’. Much of her work now was an attempt to prove what she already believed: that a significant number of Finnish migrants arrived in Alaska decades before the great waves of European migration swept westward across the Atlantic. Together with their descendants still living in the state, she was tracing the stories of men and women such as the Knaggs, and drawing new lines in the process, between here and there, between now and then.

At half-past six, when the talk had come to a natural pause, the pair insisted we should eat. ‘We will be having … stuff,’ Eva said. ‘Picnic style.’ She put her coat on and headed for the door. ‘We have lots of things to eat, but I will just go out and get some dessert.’

Half an hour later, we sat down together at a little table in the hallway, strewn with food. We ate chicken legs, salad, fruit and bread rolls, and drank cranberry juice to wash it down. Then we returned to the office and to the conversation.

In that room, filled with fragments of the past, time seemed to tighten and turn back on itself. The space was crammed with stories of those who had left their homes, reluctantly or by choice, for a life elsewhere. It was crammed, too, with the stories of those, here and around the world, who were trying to learn something of their family’s past. Eva and Maria took great pleasure in bringing those pasts back to people, telling them who their ancestors had been, where they had gone and how they had lived.

At half past nine, six hours after I had arrived, Eva and Maria sent me back out into the evening, wishing me well on my travels. In my hands I clutched the twin tokens of their generosity: a bag of files and papers in one, a bag of bananas in the other.