SEAWARDS THE SUN was burning off the mist, but as yet it still clung to the high plateau of the heath. The thick bush-heather was sodden with moisture and scoured Cator’s stout boots as he stumbled through it. It was August, and the heather was flowering, but in the mist it was dark and drab: more colourful were the yellow tabs of the gorse, which grew in low, scanty islands.

The heath was silent. It had little bird-life. Cator had rarely seen a snake or a lizard. Between the continents of ling and bell heather ran trackways of stones and growthless grey sand. The slanted plane of the heath was fretted with valleys and frequent ridges and hollows. Towards the sea it cut off sharply in precipitous falls, bushed and pathless.

Cator reached the mouth of one of the valleys which drove upwards to the summit of the heath. Its sides were shaggy with shoulder-high bracken in which tints of russet had begun to show. To his left, above a hard skyline, a pale disc of sun swam in the vapour; for brief seconds it warmed the valley with a surge of colour, then chilled and faded in fresh wrack.

Cator plodded on. Up the valley ran a track, but it was narrow and impeded by the wiry heather. Once, where it crossed a burn of sand, he checked his stride, seeing there the print of a horse’s hoof. A recent print . . . ? Cator couldn’t be certain. Not many riders ventured this way. He planted his boot on the half-moon, leaving in its place a pattern of nails.

Now he was half-way up the valley and approaching its solitary landmark. This was a ragged thicket of hawthorn and bramble, drooping down the right-hand slope. Nearing it, Cator paused again. He had noticed an object at the foot of the hawthorns. Dark and still, it resembled a small heap of wet, discarded clothing. Somebody lying there? That seemed unlikely, in the early-morning mist. Cator’s breath came faster. He began to lope forward, careless of the heather that soaked his ankles. He reached the hawthorns. He saw death. Cator wasn’t afraid of death. A farm-worker, he was familiar with the stiffened carrion of dead animals. The animal here was a man-animal, but Cator saw it without shock: he stood staring, breathing through his teeth, trying to understand what he saw.

The body was male; it was wet; it was stiff; it had received damage. It lay on its back with one arm thrown up and the other evidently fractured, and the hand crushed. One leg also was apparently fractured and the chest had a curious, sunken appearance. The features were partly pulped and they retained a semicircular impression in the broken flesh. Around the body were signs of disorder. Cator noticed scuff-marks in the sand. An area of heather-bush had been churned up and several of the embedded flints were kicked out.

Though he’d never met such a thing before, Cator could guess what he was looking at: this man had been savaged by a horse. It had left its signature in his face.

Cator felt horror. He took some steps backwards, when suddenly the sun broke through behind him. It lit the dank side of the valley and coloured the mist still heaped above it. And on the mist, printed high and clear, was the rainbow shadow of a gigantic horseman, sitting motionless, his horse still, his face turned, watching Cator. It was the illusion of a moment; then the mist closed again. The rasp of Cator’s breathing had been the only sound to accompany the phantasm.

Cator ran. He dashed up the valley, his legs pumping like machines, boots squeaking in the heather, arms thrashing the moist air.

On a ridge behind him sat the horseman whose presence had occasioned the phenomenon.

He was dressed in black, and rode a black horse.

He chuckled, watching Cator run.

‘Does the name Lachlan Stogumber mean anything to you?’ the Assistant Commissioner (Crime) asked Gently.

Gently considered it, making at the same time a swift mental review of the morning papers.

‘Is he a pop singer?’ he ventured.

‘Not a pop singer,’ said the A.C.

‘Does he play for Spurs?’

‘He isn’t a footballer. At least, I wouldn’t think it likely.’

‘Well . . . a Black Power leader?’

The A.C. grinned. ‘Admit it,’ he said. ‘You don’t know him. The man Stogumber has made no mark in your nasty, criminous little sub-world.’

Gently rocked his shoulders. ‘My loss,’ he said. ‘So who is Stogumber – among the elect?’

‘The elect,’ the A.C. said, ‘being the pot-smoking stratum and presumably the editor of the New Statesman. He’s a poet.’

‘Stogumber is a poet?’

‘According to the authorities quoted. He’s the young Byron of the jazz idiom. Allow me to make an introduction.’

The A.C. picked a copy of the New Statesman from his in-tray and folded it back at a marked page. Gently accepted it without enthusiasm; a culture session was not among his priorities. The Assistant Commissioner, it was as well to know, had himself published verse when at Cambridge: he had been a near-contemporary of Auden and Spender, and rather viewed himself as leaguing with them. The politic didn’t lightly enter upon these topics with the A.C.

‘Read it,’ the A.C. said. ‘Give me an opinion.’

Gently fidgeted. ‘This isn’t my century. I’m a little Après-Keats-le-déluge.’

‘So try reading Stogumber,’ the A.C. said.

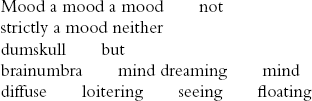

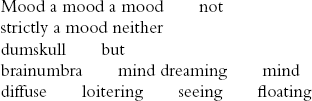

Gently sighed, and tried reading Stogumber. Stogumber was less enigmatic than Gently had feared. His title, A Mood A, was not explicit, but the words that followed had a wistful coherence.

Gently cleared his throat. ‘Interesting,’ he said. ‘It could be a code, but probably isn’t.’

‘There you go,’ the A.C. said. ‘I think Stogumber has passion. I’m not sure that I’m sympathetic with his excursions into punctuation, but I like his energy, and the shrewd picture of a creator stuck for a subject. Brainumbra – rather fine.’

‘Yes,’ Gently said. ‘But what’s he to us?’

‘I’m coming to it,’ the A.C. said. ‘Briefly, Lachlan Stogumber had a brother-in-law called Charles Berney – a brewer.’

‘A brewer,’ Gently said. ‘Berney’s Fine Ales and Stout?’

‘They’re the people. They were taken over by Watney’s in a reshuffle a few months back. Berney was given a seat on the new board and the usual office and pseudo-job, very pleasant. It left him free to pursue what was apparently the hobby of a lifetime.’

‘But Berney is dead?’

The A.C. nodded. ‘He died on Tuesday. He was trampled by a horse.’

‘So what is our interest?’

‘Just that. The Mid-Northshire Police are uneasy.’

Gently stared blankly. ‘But it’s an Act of God – being trampled by a horse!’

The A.C. nodded sympathetically. ‘And a ruling you would expect to appeal to constabularies in the remoter provinces. Brewer stricken by Act of God. Divine judgement on Berney’s Fine Ales. It must be all this box-culture that’s destroying the simple faith.’ He rubbed his chin. ‘Berney was a womanizer. That was the hobby I mentioned. He appears to have been keeping an assignation when he got mixed up with the horse.’

‘What’s the woman’s story?’

‘She hasn’t been identified.’

‘Who owns the horse?’

‘They haven’t found it.’

‘So,’ Gently said. ‘No horse. No woman. Just a brewer dead from injuries. Why couldn’t he have been knocked down by a bus?’

‘Because it happened on a heath,’ the A.C. said.

The A.C. graciously ordered coffee, which was fetched by a policewoman of elegant statistics. The A.C. drank his coffee waspishly, like a man remembering cigarettes.

‘Of course, Mid-Northshire may have made a cock-up and offended some people round there. Berney could have been savaged by a stray. You wouldn’t expect the owner to come forward. Then the local Keystones move in demanding alibis and insinuating adultery. Last resort: call the Yard, try to make it look real.’

‘Is that how you read it?’ Gently asked.

‘Smoke if you damn well have to,’ the A.C. said. He licked his lips and put down his cup. ‘It gives me that impression,’ he admitted. ‘Berney was a womanizer – fact: but they have no evidence of a current affair. And against that he remarried only three months ago. You’d think he’d still be resting on his laurels.’

‘Perhaps his carefree past caught up with him,’ Gently suggested.

‘Blackmail?’

‘Berney would have money.’

‘Why kill him then?’

Gently shrugged. He began to fill his pipe with Erinmore.

‘Berney was forty-five,’ the A.C. said. ‘He gave a birthday party on Monday. Acting normally, you’d say, showing no signs of strain. But next morning he told his wife he had to attend a directors’ meeting in London, which involved staying overnight. And that was a lie. There wasn’t a meeting.’

‘The classic storyline,’ Gently said.

‘Yes, well,’ the A.C. said. ‘But what he actually did was to drive to Starmouth and book a single room in the name of Timson. Note, a single room. No suggestion of a Mrs Timson to follow.’

‘Perhaps she was already there.’

‘Then Berney would still be alive.’

Gently puffed. The A.C. made an impulsive fanning motion.

‘And that’s it – we lose sight of him after he booked at the Britannic at Starmouth. He left in his car at around ten a.m. and some time after that drove to High Hale heath. His stomach contents say he ate a picnic lunch, and there was an empty Thermos flask in the car. He died around four p.m., about a mile from the car, on a remote part of the heath. He wasn’t expected home, so no alarm. A farm-worker found him on Wednesday morning.’

‘And a horse did it – and that’s all they have?’

‘There isn’t much else,’ the A.C. said. ‘They have a witness who saw a horseman on the heath Tuesday afternoon, but too far off for identification. Apparently there’s a riding school three miles away, and they occasionally take riders to High Hale heath. But nothing on Tuesday. The only horse on the spot belongs to a farmer, and that’s accounted for.’

Gently puffed. ‘Then was it a horse?’

The A.C. hesitated. ‘They seemed pretty sure of it.’

‘You could run a man down, dump him on a heath, plant a few horseshoe marks around him.’

The A.C. stared a moment, then shook his head. ‘I don’t think you could get away with that trick. Vehicle-collision injuries are too distinctive. It would need more than faked hoofmarks to pull it off. And don’t forget the horseman.’

‘I wasn’t forgetting him. Somebody saw him a great way off.’

‘He was there,’ the A.C. said. ‘That’s the point. If his presence was innocent, you’d have thought he’d have come forward.’

‘Huh,’ Gently said. He brooded a little. ‘Where did Berney live?’ he asked.

‘At High Hale Lodge.’

‘Is that near the heath?’

‘I don’t have that information,’ the A.C. said.

Gently blew a lop-sided smoke-ring. ‘So Berney takes a day off,’ he said. ‘He’s expecting it to be a night off, too, and he books a room, name of Timson. His wife thinks he’s gone to London, but as far as we know he didn’t leave the district. It reads as though he drove straight back to High Hale, parked, then waited to keep an afternoon rendezvous. Was the car concealed?’

‘Yes,’ the A.C. said. ‘It was driven on the heath and parked out of sight.’

‘Just making points,’ Gently said. ‘But why did Berney wait about there so long?’

The A.C. frowned. ‘We don’t know that he did. There’s no evidence that he drove straight back.’

‘There’s the picnic lunch.’

‘Perhaps he thought he was safest there. Driving about, he might have been spotted.’

Gently nodded reluctantly. ‘We’ll pass that for the present. Berney eats his sandwiches, drinks his coffee. Now, the theory is, he sets off across the heath to a spot a mile distant, to meet a woman. Why so far?’

‘Perhaps handy for her.’

‘Couldn’t he have parked somewhere closer?’

The A.C. gestured with his hand. ‘This is all academic! No doubt it’ll be plain enough when you’ve seen the layout.’

‘What keeps striking me,’ Gently said, ‘is that Berney went to these lengths just to meet a woman. We aren’t dealing with calf-love. Berney was forty-five with, we are told, a long history of philandering. Would this be his style? Wouldn’t you rather have expected him to have made that room at Starmouth a double?’

‘It seems more his mark,’ the A.C. agreed. ‘But we don’t know the circumstances. What are you suggesting?’

Gently shrugged. ‘Points,’ he said. ‘Checking to see if the theory fits.’

He put another match to his pipe, kindly puffing the smoke aside. The A.C. twitched a little but refrained from stronger reaction.

‘Berney meets his woman, then, and while they’re dallying they’re being watched by the aggrieved husband. The husband is mounted; is, we assume, the horseman seen by the witness. The woman departs. Berney heads for his car. The husband follows Berney and rides him down. Husband rides home, stables horse, declares an alibi. Wife supports him.’

‘Well?’ the A.C. asked sourly.

‘It’s half-way credible,’ Gently admitted. ‘The wife would be scared of the husband and would probably feel she was responsible. But the locals haven’t come up with a woman and they haven’t come up with a horse.’

‘Which,’ the A.C. said, ‘is where we came in. Go down there and find them for them, Gently.’

Gently sighed and rose.

‘Any message for Lachlan Stogumber?’ he asked.

‘Tell him to use aspirin,’ the A.C. said. He was reaching for an aerosol as Gently left.

There was mist again on the heath, lying low and smoky in valleys and hollows. The western sky held a tender pink afterglow banded by still, heliotrope clouds. The cool plain of the sea below took a tinge of the pink in its slaty flood. Overhead a few stars prickled. No scent came from the dank heather.

A man was seated on one of the ridges and he had binoculars slung round his neck. He sat as still as the stunted thorn-bushes that grew in a screen about him. He watched and listened. Suddenly, quietly, he raised the binoculars to his eyes. For a long while he remained staring through them, motionless, forearms supported on his knees. Then he lowered them, but continued to sit there, the damp twilight thickening round him. At last he heard a sound, a long way off: the sound of a car engine being started.

Then the man rose, getting up stiffly in a way that showed he was no longer young. But he was tall and strongly framed; very silent in all his movements.