In recent years the political modernism that emerged following the events of May 1968 has come under review within the academies of Europe and North America. The critical revisitation of political modernist thought and practice has raised reflection upon the theory-practice frameworks and approaches for developing critical and politically interventionist praxis. The political modernist discourse in film was not unified or monolithic; its intellectual trajectory spanned Marxism and psychoanalysis, bound with a common concern – the relation of film to ideology (Rodowick 1994: ix). The principle criticism of political modernism has been its simplification of the theory-practice interface in terms of the idealised and simplistic binarisms pertaining to code/ deconstruction, transparency/reflexivity, and illusionism or idealism/materialism. According to D. N. Rodowick the dualisms of political modernism were portrayed as a ‘dialectic’ that ‘obscured the importance of theory in the study and critique of ideology by excluding all but formal relations.’ (1994: xvi). Paul Willemen adds to this by pointing out that the counter-cinema theorists such as Peter Wollen and Claire Johnston had never posited that:

the strategies and characteristics of counter-cinema should be canonised and frozen into a prescriptive aesthetics. They pointed to the importance of cinematic strategies designed to explore what dominant regimes of signification were unable to deal with. Theirs was a politics of deconstruction, not an aesthetics of deconstruction. (Pines & Willemen 1994: 07)

Noel Burch, a key figure in the political modernist discourse, has himself attended the problematics of political modernism and its aesthetic strategies arguing that in the contemporary late-capitalist and post-modernist context, a confusion has been rendered between market, culture and political struggle. Strategies deployed in developing a theoretically informed interventionist praxis in the 1970s have been abstracted from their ideological discourse and usurped by mass media. He succinctly summarises his concern thus:

… particularly because of the way America is, always has been, having no tradition of struggle really, at least one which has completely been perverted for so long, that it has become fundamentally confused with indeed this objective illusion of capitalism and capitalist societies toward basically everything becoming market and the culture itself simply becoming a market value. The confusion is such that it is almost impossible to extricate the one from the other and this is what has broken down I think any kind of serious cultural or political resistance… (Myer 2004: 73)

In the critical revisitation of the political modernist discourse, which was articulated equally through film scholarship as through cinema practices ranging from the literary to the painterly avant-garde, one shortcoming that has surfaced is the cultural opacity of film theory and the avant-garde generally. This sentiment is most clearly articulated by Robert Stam who states that the discipline of film has for long; ‘sustained a remarkable silence on the subject’ of race and ethnicity’ (2002: 663). While scholarly interests in issues of cultural difference have increased in recent years particularly with the ascendance of fields such as cultural studies and postcolonialism, Stam problematises the common modality of text analysis focussing on racial and ethnic stereotyping, particularly within mainstream cinema, such as Hollywood. According to Stam the stereotype approach necessarily formulates into pre-occupation with positive and negative images leading to a kind of ‘essentialism’ and ‘ahistoricism’, ‘… as less subtle critics reduce a complex variety of portrayals to a limited set of reified formulae’ (2002: 663).

Filmmaking practices from the ‘third world’ such as South American guerrilla and social cause-espousing documentaries from South and South-east Asia are constantly gaining exposure and interest in the Western academies and festival circuits. They offer to the Western academic and viewer the possibility of an interventionist praxis standing in for political struggle. While the ascendance of interest in third and subaltern cinemas, practices and issues of representing ethnic and cultural difference, alongside a closer meditation on post-colonial frameworks and discourses widen the scope of film scholarship and confront the universalism underpinning modernism generally; the sorts of cultural and ethnic issues as well as the strategies for attending those that have developed thus far are fraught with certain risks. Third-world Marxist scholars have consistently alerted that there is a ‘certain urgency in the task of the third world inside the first’, but they emphasise that it is imperative a third worldist mentality does not get perpetuated by this process (Kapur 2000: 281). Art historian Geeta Kapur asserts that the representations of radical issues in the third world should not inadvertently get overdetermined by the first world (2000: 281). Further, any gesture towards cultural, ethnic or racial subjects in Euro-American liberal contexts need to be disentangled from the wider public discourses of cultural diversity that overlook cultural specificity and social historicity in their celebratorily inclusive modes. Lastly, and most importantly in the study of cinemas outside Europe and North America it is pertinent to work with theoretical criteria with extreme caution so that concepts developed in one cultural context do not get summarily deployed in reading texts from distinct cultural contexts. This does not mean that theories and discussions developed in Euro-American academies cannot be applied in studying third and subaltern cinemas. What is necessitated is the careful application of different theoretical criteria with an understanding of their limits and strengths while in application in differing contexts.

In this chapter, I aim to examine the documentary oeuvres of two prominent filmmakers working in the Indian subcontinent to unpack the theory– practice interface in their works in order to highlight how cultural specificity and socio-historical disparities impact the interrogations and strategies practitioners develop. Avant-garde artist Kumar Shahani and acclaimed ethnographic filmmaker David MacDougall, through a complex oeuvre bring forth for us the possibility of a phenomenological engagement in documentary that serves in contextualising and problematising post-coloniality generally and its impacts on the body specifically. The documentaries of Shahani and MacDougall present us with a complex matrix of considerations and practices that facilitate working through the issues and concerns pertaining to a radical and interventionist practice that have arisen in light of the critique of political modernism.

The key question pertaining to the theory–practice interface in film education spans issues of how students critically engage with their creative impulses, the histories and philosophies linked to the media they work with and the wider exhibition and distribution networks they explore and within which they situate their practice. These are not merely pragmatic or practical concerns. In inhabiting these questions, it is aimed a student, prospective film practitioner, can critique and contextualise his/her work as an intervention in thought. Shahani and MacDougall work within very distinct disciplines—the former a radical and independent avant-garde filmmaker from the subcontinent who has questioned the terms of reference for an interventionist practice both within and outside the Indian subcontinent developing practice that boldly inaugurates the interface of Indian classical, folk and philosophical traditions with documentary. MacDougall is an ethnographic filmmaker whose films in India make for students and aspiring documentarists a rich resource of deeply thought discursive and aesthetic modalities pertaining to observational cinema. The discussion in this chapter is divided into three sections. In the first, I contextualise Shahani’s documentaries surrounding Indian arts and cultural practices, to explicate how his films first formulate as a radical critique of mainstream Indian nationalist ideology, and second, how his aesthetics, particularly the use of the long-shot extend conventional film theory discussions. In the second section, I examine MacDougall’s school films in India to exposit how they attend the shaping of the body in a postcolonial context. Alongside this critical perspective, I share MacDougall’s development of a phenomenologically-informed haptic visual regime that links with early cinema modes of representation to argue how his documentaries stress viewership into perceptually complex realms. The conclusion to this chapter summarises how the specific strategies of both filmmakers emphasise the formulating discourse between filmmaker and subjects and how that is articulated subjectively and expressively into a historically critical and aesthetically complex formulation that presents to the student of film the convergence of socio-cultural and historical imperatives on the body – of both subject and filmmaker, thus lending sociality and historicity to issues and techniques such as self-reflexivity in practice. This is a necessary move for student-practitioners so that the techniques they work with get contextualised socio-historically rather than deployed as essentially laden with specific meanings only, extracted and abstracted from their historical contexts.

CLAIMING CLASSICISM

Within the context of the Indian subcontinent, documentary film tends, in a summarily reductionist gesture, to often get posited as antithetical to the mainstream fiction film emerging from industries such as from Mumbai or Chennai. As against Bollywood, which is perceived as selling dreams, fantasies and escapist entertainment, documentaries are considered as more serious and ‘real’. While not totally invalid in the stated context, the terms of reference for such a polarisation have stressed documentary practice into a largely social-realist modality, identified with a largely mass-communication determined informational and educational function. This perception of documentary reflects an understanding of moving image technologies as a media for recording ‘reality’, in a sense that lacks the deliberation upon the scope and efficacy of the cinematographic apparatus that has occupied film theory since its inception. The sole identification of documentary’s claim with a will to preservation has overdetermined image and sound as largely evidential and socially functional components. This reduction of the scope of documentary to issues of social cause and argumentation based on the equation of film components with truth and veracity has had its critics and has festered a generation of practitioners seeking more innovative and creative approaches to practice.

After India’s independence in 1947, the Films Division – a public agency geared towards promoting documentary film production – was set up in 1948. In its first two decades the Films Division extensively supported documentary projects. Implicated closely in the euphoria and celebratory discourses surrounding a newly formed ‘nation’ documentary practice got linked to goals of information, education and propaganda. Though the division supported masters such as Satyajit Ray and Sukhdev, within successive years a scourge of bureaucracy overruled it and documentary film form got institutionalised. Experimentation and innovation at the level of form were undermined as documentary got increasingly burdened with social realist investments of a peculiarly reductive, functionalist modality bearing closest proximity to television and broadcast documentary films that are made under particular time and budgetary constraints that affect both content and form. Critic Amrit Gangar vociferously and succinctly summarises the impact of the Film’s Division on documentary filmmaking in India thus:

The Films Division’s virtual stranglehold has another fall-out besides a definite “distaste” for documentaries that it has been able to create among the minds of people. The more serious fall-out is that the FD has also eventually muffed up the voice of documentary – the voice largely in the sense of stylistic expression, its various possibilities and alternatives. This government outfit makes its films largely by risking aesthetic issues, notwithstanding the fact that it has on its shelf some “award-winning” or really significant films by filmmakers such as Sukhdev, Satyajit Ray and Mani Kaul… (Chanana 1987: 36)

The institutionalised practices of the division came under criticism from filmmakers for jeopardising the scope for an ideologically critical and formally experimental documentary practice. This critique was the foundation for independent documentary filmmaking in India and fashioned the discourse underpinning it. The independents developed a critical posture against the hierarchical and hegemonic, institutionalised discourses of the nation. This led to documentaries determined by the investigative and interpretive modalities – documentaries assuming an activist posture for espousing socio-cultural causes alongside historical issues. While such an activist agenda deservingly bears a function within the wider rubric of a democratic and developing society, in terms of filmmaking it tends to overplay content in documentary with an un-reflexive and under-theorised posture towards the implication of film form in practice.

A minority of avant-garde documentary work, steadily getting obscured from the pages of film history in the subcontinent, has however resisted the definition of documentary as content-oriented and a solely activist practice. This small body of practice shares with wider independent documentarists the critical stance against the nation and the institutionalised discourses and practices of documentary filmmaking as perpetuated by public agencies such as the Films Division. Kumar Shahani’s cinema including fiction and documentary is grounded in a critique of the nation in terms of the reductionist, affirmative and institutionalised worldview mobilised in the nation-building process. However his critique is enmeshed within a wider project of innovation with film form and experimentation with alternatives of narrative derived from the epic and folk forms from the subcontinent. Kumar Shahani’s cinema is characterised by a particular posture in which film form is crucially implicated in the critique of the nationalist discourse, i.e. for Kumar it is not enough to articulate a critical posture explicitly through film content as with the mass communication informed pervasive modes of independent documentary filmmaking in the subcontinent. He, like his esteemed teacher, Ritwik Ghatak, and other master predecessors including Satyajit Ray, has pursued the interrogation of documentary’s claims of objectivity, truth and ventriloquist activism through a reflexive and aesthetically variegated register of techniques. Shahani’s documentaries make for a body of work that challenges the dominant documentary discourses in the Indian subcontinent and cut into some critical theoretical debate and discourse internationally.

Shahani trained under Ritwik Ghatak at the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune. Ghatak was a contemporary of Satyajit Ray and the two filmmakers emulate pronouncedly disparate ideological postures. Both Ray and Ghatak were deeply influenced by the discourse of the modern Indian poet, litterateur, artist and thinker, nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore. Central to the Tagorean discourse is the denunciation of the nation as a ‘rapacious and illegitimate category’ (Nandy 1994: 2). The cinema of Ray and Ghatak emulates a critical posture against the nation through very distinct visual discourses and strategies. Ray derived hugely from neo-realism and formulated it, given his liberal and upwardly mobile background, into an ‘orientalist naturalism’ through which he mapped the aching transition of a society from rural feudalism towards progressivist modernity. This is best exemplified through the internationally acclaimed Apu trilogy (1955–60). Ray’s nostalgic take for the rural past being lost at the altar of modernity was the mode and extent of his critique of the post-independence nationalist discourse emphasising modernity in affirmative terms (Kapur 2000: 201–32). Ghatak, on the other hand, was hugely influenced by Sergei Eisenstein. He used Eisenstein’s montage principles to critique Bengali Hindu conservatism, particularly its take on gender. This critical posture is rooted in Ghatak’s sense of exile having migrated from East Pakistan during the birth of the independent Indian and Pakistani nations. The exilic discourse led to psychologically expressive cinematography and use of critical montage juxtaposition to disassemble the category of Indian traditions being mobilised in a nascent nationalist rhetorical jargon and imagination (Dunne & Quigley 2004).

Shahani derives from Ghatak but extends his approach towards the cultural and aesthetic traditions of India. His approach is more experimental and innovative towards film form. He attempts to claim Indian aesthetic and philosophical discourses but in a historicised and contextualised gesture far distinct from the celebratory, affirmative and reductive assertions of India’s past in the wider, more institutionalised and rhetorical discourses of nationhood. In this way Kumar’s cinema formulates as a truly independent practice – one that is not determined by, or solely in opposition to the hegemonic national-statist institutions and apparatuses. His cinema is at once critical and poetic – constantly exploring, configuring and reinventing its own terms of construction and aesthetics. His approach is holistic with film form and content being tightly intermeshed.

Shahani’s documentaries on the arts in India focus on the idioms of dance and music – both classical and folk. Bhavantarana (1991) is a grand documentary of epic scale, an hour-long rendition spanning the life and work of the Odissi dance maestro Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra. Besides Bhavantarana, which is internationally acclaimed as one of his finest efforts, Birah Bharyo Ghar Aangan Kone (The Bamboo Flute, 2000) and As the Crow Flies (2004), are other documentaries surrounding the arts in India. The former is a documentary rendition of the flute using as its impulse the Indian spiritual and philosophical discourses surrounding the instrument wherein it is metaphorically equated with all organic life. The latter is an evocation of the painter Akbar P. Adamsee’s work.

Bhavantarana is structured around the thinly linked interplay of dance sequences and dramatic reconstructions of key instances from Guru Kelucharan’s life. The dance sequences include solo performances by Guru Kelucharan and his dance classes where we see him training dancers. Kumar’s selection of Odissi, as indeed the Indian arts generally as the subjects for his documentaries constitutes as a radical political gesture. As indicated above, in its early decades the Films Division had emphasised informational, educational and propaganda films emphasising the cultural heritage of India. A series of travelogues, mapping geographical landscape, aesthetic and cultural practices had been developed to mobilise, among audiences across India, a sense of coherent and cohesive history and unity. Under the aegis of the Films Division such representations had tended to be quite celebratory underpinned by a near rhetoric emphasising the diversity in Indian society as the foundational ethos of a new nation. As filmmakers became critical of the Films Division’s propagandist posture, and alert to its usage in masking the nation’s normative discourses grounded in the mechanisms of displaying, patronising and excluding ethnic and cultural minorities it became, and continues to be quite problematic for independent filmmakers to engage with any aspect pertaining to India’s cultural heritage – the risk always being the appropriation of such representation into a mainstream discourse celebrating nationhood. For many filmmakers this has meant completely deserting India’s arts, aesthetic practices and cultural heritage discourses, thus further grounding the understanding of documentary in socially functionalist terms. In this light Kumar’s documentaries assume significance for their boldness in claiming and bringing into the cinema India’s aesthetic, philosophical and cultural discourses without slipping into ahistoricised or reductive essentialism.

Kumar Shahani’s Bhavantarana (1991)

Kumar’s documentaries are acclaimed for their elegant choreography of performers and the camera. Bhavantarana is structured around two parallel narratives. At an immediate level the narrative pertains to the life of Guru Kelucharan, suggested through minimal dramatisations of key instances from his life such as his decision to pursue Odissi, marriage and dance training. These sequences are interlaced with sequential renditions of the master’s body as dancer/ performer. These sequences of dance catapult the film away from a chronological documentation of Guru Kelucharan’s life towards an experiential realm. In documentary terms, these sequences formulate as an observation of the dancer’s body in performance. This is historically extremely valuable as a visual record and archive of the master’s works, given that India’s defence budget and aggressive economic growth rates leave little by way of any funding for the arts or cultural heritage preservation and dialogue. In the dance sequences Guru Kelucharan performs a spread of mythical and epic episodes from India’s ancient classics. Besides the intricacy and finesse of his expression, one cannot but marvel at the refined and highly perceptive performance that reveals his depth command over the dance. In the highly evolved idiom of Indian classical forms, Kelucharan’s performance reflects a unique mix of individual expression melded with a tightly structured dance tradition.

Kelucharan was in his late seventies when Bhavantarana was developed. Shahani had researched the project for nearly a decade. The dance sequences in the film bring to life the splendour and grandeur of Kelucharan’s body in performance. In ethnographic terms, the camera serves as an observer-participant – a position that favours observation over participation in the processes being documented. This results in a very specific and contained cinematographic design. The camera maintains enough distance from the performer through which his body is largely seen in full, without being fragmented or objectified. Shahani uses long shots that fully accommodate the dancer’s body and more importantly, situate it in context, i.e. the natural landscape in which the Odissi dance form is rooted and from which it derives its vocabulary. Bhavantarana is shot in the exteriors of rural Orissa, amidst either a thick, lush green backdrop or on the sea-coast. These images are reminiscent of the opening shot from Maya Deren’s Choreography for the Camera (1945) wherein the dancers’ bodies are seen in an exterior location, amidst thick foliage. A fine usage of depth-of-field links the performer and landscape and through this the cinematographic apparatus emulates the ecological worldview informing the dance. In the classical forms, the performer and performance are considered as co-extensive of temporal and spatial coordinates. This understanding is at the heart of the principle of embodiment in performance and derives from the aesthetic discourses of Indian art that bear an ecological approach i.e. art is the instance whereby the artist, the object of perception and the perceiver meld and share in unity.

Landscape is thus not merely a location backdrop in the classical practices, instead artistic expression is tightly linked to and derives from it. The long shot melds the dancer’s body with the backdrop and this specificity in terms of site, here involving a regional definition pertaining to India’s eastern coast, bears ethnographic relevance in terms of contextualising the dancer as embedded in a culturally inscribed landscape. This coupled with the short dramatisations of Guru Kelucharan’s life through which we gather a sense of the meagre resources at his disposal to pursue dance historicise his practice and body as a socialised composite in a post-national context. These devices are crucial as they resist appropriation of the dancer’s body within a wider nationalist or propagandist representation that tends to valorise the dancer’s body by abstracting it from space thus propelling an ahistorical and essentialist projection. A liberal democratic sentiment in the Indian context is marked by a celebratorily inclusive gesture whereby disparate cultural traditions and practices are all posited as mingling as in a mixed salad. The regional, aesthetic and historical disparities, and also the contemporary conditions surrounding the various arts of India are evaded, and this ossifies these practices, foreclosing the possibility to understand and interrogate them as living traditions. By consistently bringing in the contemporary context in which Guru Kelucharan performed and taught Odissi dance, Shahani provides us with a historicised and ethnographically precise understanding of the dancer’s body and this prevents Bhavantarana from slipping into what at first might seem like a purely exoticist representation given the film’s occupation with a visually clearly oriental subject.

While we see Kelucharan performing through long shots, through single-point, diagonal lighting we experience a sense of nearness with his body whereby the most minute and intricate gestures and movements: facial, hands, feet and even those of the muscles are clearly registered. Camera movement in these sequences is measured and sustained—becoming a kind of responsive choreography. The camera is never hand-held and that complements the flow of fully embodied, conscious and sustained movements performed by Guru Kelucharan in dance. While the camera observes the dancer’s body and the will to preservation cannot be separated from the film, the film text extends beyond that imperative to create a newness in which the dance experience is altered through the input of camerawork and editing.

Douglas Rosenberg, founder of the Dziga Vertov Performance Group in the USA in 1991, asserts that: ‘There are numerous approaches to the practice of creating dance for the camera’, however there are similarities in that all approaches ‘place the choreography within the frame of the camera and offer the makers the opportunity to deconstruct the dance and to alter its form and linearity in post-production’ (2000: 04). Close examination of Bhavantarana’s structuring principle reveals a constant use of stark juxtapositions of block frames with continuous action. Sharply juxtaposed locations lead to visual variations in the middle of intense performance sequences. The juxtapositions of landscape have a more stark effect on viewer perception given that the dancer’s movements in the foreground maintain a narrative continuity. This is again reminiscent of Deren’s Choreography for the Camera, where a dancer begins a movement in one shot with a clearly defined background (filmed at a specific camera magnification) and the movement is completed in another shot with a starkly varying background and magnification. Through this continuity of action but juxtaposition in location, the dance performance deconstructs the organisational principles of the dance. This does not destabilise the organic unity of the dance form however the camera’s intervention including editing does alter the perceptual experience of the dance. This is a very crucial move as the camera’s subtle restructuring of the dance makes the documentary exceed the functions of record and preservation, and in the national context, this interplay with form becomes a critical gesture. An organic dynamic emerges between the dancer and the filmmaker. This stresses the film beyond ‘re-presentation’ of dance, towards a new creative unity embedded in the eliciting discourse between filmmaker and dancer actualised through form. In ethnographic terms this is a modernist take at cultural documentation grounded in poly-vocality if we include voice in the structuring principles of the film text.

With respect to the discussion surrounding the theory–practice nexus in film education, Shahani’s corpus – including films such as Bhavantarana – presents us with a few interventions that enable in thinking about film praxis as a medium for critiquing dominant and hegemonic ideological systems, without necessarily reducing the question of the critique of ideology to an aesthetic issue or one exclusively surrounding film form at the cost of film content. Shahani’s use of the long shot and depth-of-field, discussed above in the stated context is a strategy that counters the appropriation of culture through a summarily reductionist, ahistorical and propagandist gesture on behalf of the institutionalised-statist apparatus. The long shot contextualises as in Bhavantarana, the Odissi dance within a regional, cultural landscape. Film theory, as it has developed in the Western academies has consistently critiqued dominant ideology as exemplified through cinematic conventions of mainstream industries such as Hollywood. Critical practice was thus posited as including ‘deconstruction’ of mainstream cinematic conventions.

In film theory, the long shot and depth-of-field have been conventionally equated with cinematic realism as theorised by André Bazin, who is often, simplistically projected at odds with the modernist theorists and practitioners – namely Sergei Eisenstein and Rudolf Arnheim. Shahani’s use of the long shot and depth-of-field serve as critical tools that ethnographically contextualise and historicise the subjects of his films. As argued above this contextualisation serves as a mechanism for countering the hegemonic and institutionalised discourses of the nation state, which in the context of a visual discourse propel ahistoricised and essentialised representations of India’s cultural practices. More internationally, Kumar’s aesthetics intervene in complicating the neat binarisms upon which the categories of realist and modernist cinema have been founded.

After training with Ghatak, Shahani worked under Robert Bresson in France in the late 1960s. In 1968 he was introduced to Jean-Luc Godard who had invited Shahani to join the Dziga Vertov Group. Kumar engaged with Godard over the question of developing an ideologically critical cinema practice. He, however, disagreed with the equation of ideological critique through cinema as a question of deconstructing dominant codes of representation only. For Kumar it was limiting to think of a radical praxis in terms of reversing codes and conventions associated with the mainstream and dominant cinemas. Shahani summarises his concern thus:

The theory that there exists a Cartesian polarity between arbitrary (aesthetic) signs and total realism necessarily led to quantitative conclusions and meaningless oppositions: the proliferation of detail against metaphysical truth (where quality cannot be seized), the fluidity of mise-en-scene as against the metre of montage, the existential tension of suspense (Hitchock) as against the tragic release from pity and fear. The terms of reference were purely idealist: the human being unsocialised and nature untransformed. Or when socialised or transformed, superficially so. This attitude necessarily tended either to exclude syntax progressively (realism) or to impose it as totally arbitrary structures. (1986: 72)

Shahani’s criticism of the ‘realism-modernism’ polarity perpetuated by film theory raises issue with the equation of the discourses of realism and modernism with cinematic code i.e. depth-of-field equates with realism and montage with modernism. This, according to Shahani is limiting as it ossifies cinematic codes and techniques as embedded with only one set of meanings, supporting one form of discourse or worldview only. His own work has revealed that while a critical practice cannot be separated from the deconstruction and reworking of dominant cinematic conventions, it calls for the reconfiguration of form and content in terms of context—that within which a filmmaker works and that of the subject he/she documents. This implies the filmmaker and subject as both socialised and historicised bodies. Shahani’s emphasis on the subject as a ‘socialised’ category is not simply in terms of historico-cultural definition, instead it involves interrogation of the terms at which the body, be it the filmmaker or the subject, is represented and appropriated in varied discourses including the normative national. This has led to in his case a departure from one of the key philosophical discourses within India – the advaita (the philosophy of the non-dual self).

According to Shahani social contradiction and spirituality are not oppositional or antithetical categories as some of the key philosophical schools such as the advaita in the subcontinent as also sections of Marxist thinking in the subcontinent and the west have made them out to be. For Shahani the spiritual imperative underpinning art cannot be abstracted from art’s role as a mode of politico-ideological critique. Neither, according to him, does attending social or political conflict through art amount to a reductive commitment to material reality as against the immaterial and contemplative pursuit. He states:

In our own little environment here for instance, most of the people who speak in the philosophical tradition of Advaita make what I think is a very big mistake. It’s as if social contradiction doesn’t have anything to do with the spiritual—that the two are divorced, polar opposites. They want to exclude social contradiction from spiritualism. These exclusions are really evasions. Those who have taken this or the other position are evasive. They deny that the very being who is stating or taking a position is a material being always seeking spiritual freedom. Within pre-religious thought or paganism, spiritual freedom is recognised as an aspiration. In our own context this is clearly the pursuit of mukti or moksha. The body is not denied. Society is not denied. Contradiction is not denied. Mahabharata and Krishna’s discourse of the Srimad Bhagvad Gita is based on this—how the material conflict is entwined with the spiritual quest. See any of our epics, or for that matter Homer. The first Sanskrit dramas always acknowledge social contradiction and spiritual pursuit. I always hope that Marxists would recognise this, because Marx himself did – the fundamental contradiction of capitalism that it will end up paying the one who binds the book more than the poet. Marx said this so clearly and indisputably. To me there is no contradiction between the spiritual and the political. Art is obviously spiritual. And its impulse you can barely name or say it is out there. It is not an objective thing. The objective thing is perhaps only the lens. But what it is that makes art cannot be instrumentalised. Any instrumentalised art or mass communication object will eventually boomerang. (Sharma 2007: 206)

Within the context of the theory-practice interface in film education Kumar Shahani’s culturally grounded documentaries extend the understanding of radical film practice beyond a socially-functional, ventriloquist agenda as in the context of the Indian subcontinent and the ‘third world’ generally. More internationally his films present to us an alternative whose occupation for radicalism extends beyond the deconstruction of cinematic codes and conventions. Kumar Shahani’s films constitute a critical discourse within the context of institutionalised worldviews and practices in India. Their aesthetic arises from Shahani’s consistent engagement and focus upon the eliciting discourse between the subjects of his films and himself representing the wider cinematic apparatus in ideological terms. Shahani’s filmic discourse emphasising sociocultural specificity is the basis for the critical posture he develops through his practice. Through this he constantly raises questions of historicity in documentary practice. If Shahani’s cinema is deployed for encouraging students to think about filmmaking as a mode of ideological critique, then through him we are extending the terms of reference for what constitutes as radical film practice beyond an occupation with cinema onotologically in terms of cinema codes and the worldviews they represent. This is merited on two grounds. One, the terms of reference for thinking about cinema vary in disparate sociocultural and historical contexts – an aspect that the political modernist discourse and how it influenced film education in the Western academies has completely evaded. Two, Shahani’s emphasis on cultural specificity enables in a more nuanced and politically sophisticated gesture to understand and reconstitute what constitutes as radical in historically and socio-culturally variegated contexts. Therefore radical practice cannot be determined by one set of objectives alone. Shahani’s cinema arises from a position critiquing the dominant national and state apparatus. In doing this, his documentaries do not only attend questions of history and culture, but makes central to the filmmaking the question of how the eliciting discourse between filmmaker and subject effects documentary aesthetics.

OBSERVATIONAL DOCUMENTARY

David MacDougall’s ethnographic films and theorisation surrounding them constitute a complex project on the scope and dynamics of observational cinema. His sustained study of post-colonial formations and conditions in India, presents to us not only a richly textured view of the social, cultural and class formations in India, but also furnishes for the student of documentary an intricately fashioned body of work shaped principally through the discourse between subject and filmmaker/ documentarist as observer in phenomenological terms. Conventionally ethnographic research methods are divided into two categories – the participant-observer and observer-participant modalities (Seale 1998: 222). As ethnography has critiqued its positivist credentials and reconfigured its scope as a modernist practice, the former has come to be emphasised as a more subjective, indeterminate and reflexive practice. Participant-observation is a conjunctural practice developing the documentarist as participant’s experiences as the basis for documentation. However, the two positions of the participant-observer and observer-participant are not necessarily antithetical, or in any hierarchical equation, as the emphasis on participant-observation has inadvertently made them out to be. Both modalities suit variegated field research and filmmaking contexts as critical and creative tools for documentation, and the observer-participant modality itself raises modernist possibilities for subjective, expressive and critical documentation as MacDougall’s cinema shows to us. MacDougall’s observational documentaries are decisively experiential and dialogic, privileging the sense of being through emphasis on touch and texture in documentation entwined with critical argument and historicisation around the subjects that he focuses upon.

MacDougall’s films are grounded in the relationships forged between ethnographers and the subjects they examine. This is at once reflexive because film content is clearly derived from the interactions—verbal and corporeal in the ethnographic instance between the documentarist and the subject. Observational cinema arose around the time that the ‘cinéma vérité’ practice of filmmakers such as Jean Rouch was taking shape. Though related to ‘cinéma vérité’, observational documentary is a distinct practice in that it does not include reconstructions or fictionalisations—approaches seen particularly in Jean Rouch’s ethnographic films. MacDougall trained at the UCLA Ethnographic Film programme, and his work springs from an interrogation of ethnographic documentary as an objective practice. This understanding at once chimes with modernist and avant-garde film practice and theory wherein the individual shot is broadly understood as ‘latently ambiguous’, available for meaning through interaction with other shots, as say in Eisenstein’s theories (Becker & Hollis 2004: 11). However, unlike the modernists for whom the indeterminacy of the moving image led to a formal occupation with issues of montage and deconstruction, observational cinema being an ethnographic practice privileges human inter-subjectivity in documentary prior to any formal occupations.

To pretend that the camera is somehow invisible and detached from the situation implies that the filmmaker’s presence doesn’t become part of the event and that the film records the action from the outside with an objective and omniscient eye. But objectivity is a fabrication. (Sherman 1998: 50–1)

Placing human inter-subjectivity at the centre, MacDougall’s observational documentaries hold the image as both a record and as partial, subjective and expressive. This has implications for understanding self-reflexivity in practice. Critiquing realism’s ‘seamless verisimilitude’, modernist cinema, be it the early avant-garde (1920s–1930s) or later, political modernism, developed an occupation with self-reflexivity (Hayward 2000: 232–8). In doing this, it tended to reduce the approaches and scope of self-reflexivity into a question of form and film code. The laying bare of cinematic devices somehow within the image through a suggestion of apparatus or through the processes of editing got and continues to be considered as the established mechanisms to reflect and imply that the film is constructed. While relevant, it is imperative that for the student of documentary the understanding of the apparatus be expanded and widened including the filmmaker as a socialised and historicised subject.

MacDougall’s approach emphasises that self-reflexivity in cinema does not comprise a finite inventory of formal codes or techniques. In keeping with the ethnographic position, for MacDougall the ‘self’ is a contested body implicated in socio-cultural and historical fashionings that are fluidly and contingently evoked in the filmmaking process. Political modernism’s emphasis on self-reflexivity through form overlooked this. The body of the filmmaker remained unsocialised if not fully ahistoricised and abstracted from the filmmaking context. MacDougall’s emphasis on the self as socialised does not amount to a radical negation of the apparatus. A broad survey of his study of prominent schools in India reflects a steadily evolving practice that makes as its basis the inter-subjective, eliciting discourse between filmmaker and subjects, developed through an expressive visual vocabulary at far remove from mainstream and dominant documentary conventions.

MacDougall’s films in India clearly evoke a cross-cultural register. They are not in the order of cultural description or interpretation on behalf of an outsider, but deploy socio-cultural disparities between filmmaker and subject as a mechanism to raise wider historical questions. Most recently MacDougall has examined two philosophically very disparate schools in India - the first is the Doon school, a prestigious boys boarding institution in Dehradun, north India, and the second, the Rishi Valley school founded by the contemplative philosopher and thinker, J Krishnamurthy. Exploring the foundational ethos of both schools becomes for MacDougall the basis for unpacking wider issues of post-coloniality.

Founded in the early decades of the twentieth century the Doon school is tightly implicated in the founding ideology and vision for a developing nation. MacDougall’s very selection of a boys’ boarding school cuts straight into questions of gender, specifically the male body within a post-colonial framework. MacDougall’s approach to the body is clearly social-constructionist and in a broad sense, the films in the Doon School series unpack how the male body gets fashioned affirmatively in relation to the post-colonial nation state. The films are structured around the observation of key events in the school calendar, everyday routines, the school’s myths and folklore, the textures of its environs and activities, all intermixed with conversations of varied modalities – some structured interactions between filmmaker, staff and students, others including classroom discussions and spontaneously conjured exchanges among students. In this way the Doon School films are clearly polyphonic – including a tapestry of variegated experiences and worldviews. The varied voices in the films are not tantamount to a celebratory or ventriloquist gesture of inclusiveness. The complexities, textures and nuances of verbal exchange between subjects reveal wider socio-cultural discourses and facilitate in accessing the underpinning and performative worldviews of each subject we encounter, thus making the films critical historical texts.

MacDougall’s conversations with student subjects in the school films do not elicit information or descriptive experiences. They are more of exchanges sharing close experiences, thoughts and interests. These conversations reveal his subtle equations with the interviewees and their mode serves more to question the efficacy and authority of the spoken word than utilise it as the sole and authoritative source of information. This approach complicates our understanding of the goals and techniques for interviews as data gathering devices. It presents an alternative for questioning how the testimonial of a subject can be interrogated and developed to unpack that which lies further than but informs words. Avant-garde filmmaker Satyajit Ray, in an early writing, had raised this problematic surrounding interviews in documentary thus:

How can we ever be sure that an interviewee is making honest statements and not merely saying what he believes is the right thing to say? To me the really significant things that emerge from spot interviews are the details of people’s behaviour and speech under scrutiny of the camera and the microphone. (Jacobs 1979: 382)

MacDougall’s films and writing also raise this problematic and he responds, stating:

Interviews in films not only convey spoken information but also unspoken information about the contexts in which they occur. They allow their speakers to describe their subjective experiences of past events, while simultaneously we interpret the emotions and constraints of the moment. (in Devereaux & Hillman 1995: 245)

The conversations MacDougall conjures in the school films situate the interview as a fluid, impetuous and contingent instance. This exceeds the conventions of interviews as data collection devices and becomes the basis through which a critical dimension for documentation is opened that in MacDougall’s work serves in critiquing the dominant Indian state apparatus and the ideological postures it perpetuates. The school films bring forth worldviews mobilised in a post-colonial framework that are inescapably linked to the national category and the individual subject’s situation within it. This is achieved through a very subtle cinematographic and editing design of the films.

MacDougall’s sustained observation of the students’ bodies complements the verbal discourses in the film and serves in a radical unpacking of social history and its transactions with individual subjectivity. The subjects consistently reference the camera and the whole gamut of their gestures and movements reveals how their bodies and its vocabularies are all intimately tied to and shaped by the spaces they occupy and that are socio-historically constructed. In some senses the ground for the school films had already been laid through David and Judith MacDougall’s Photo Wallahs (1992) a film that through a bricolage of voices explores experiences, memories and desires linked to photography as a practice introduced during the colonial era in the hill town, Mussoorie in north India. The varied voices and experiences in this film introduce the viewer to a vast spectrum of postcolonial class and subject positions ranging from the English-speaking elite on to the lower middle classes.

This project on class takes a distinct, more decisive and in-depth turn in the Doon School Chronicles (2000) that clearly gesture towards class contradictions and divides festered in a post-colonial context. The films reveal how the school envisioned and maintained a visionary zeal in the context of nation-building aims to develop an ideal male consciousness through which the imagined aspirations of a developing nation can be performed and realised. MacDougall maps a range of processes including the shaping of the male body through physical exercise, social etiquette and discipline, through to the enculturation and cultivation of a mind adept in the specifics of the nation’s history and commanding a mobility across cultures and ideas to serve progressively in the development of the nation.

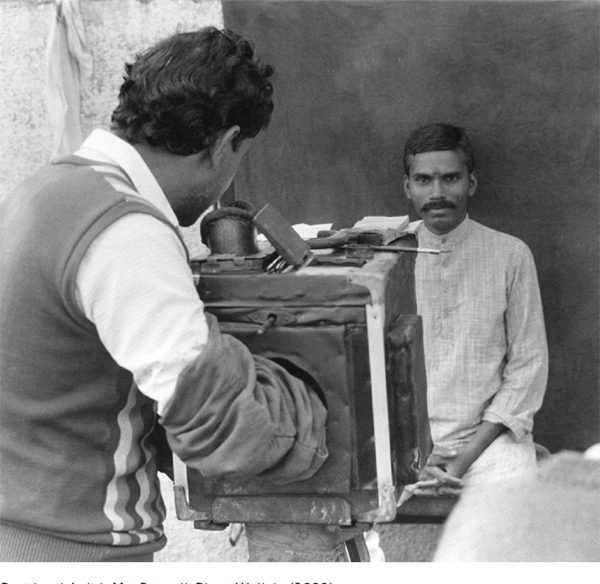

David and Judith MacDougall Photo Wallahs (1992)

The Doon School films clearly raise for us the contradictions pertaining to the oft-repeated post-colonial binarism between the categories of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’, and here ‘tradition’ does not just reference the precolonial medieval or ancient mythic and folkloric, but those traditions that are selectively extracted and encumbered by the ruling elites in the euphoria surrounding new nationhood and the norms deployed in fabricating its definition. The textures of the students’ everyday activities, body gestures and fashionings – classroom organisation, the learning processes in and outside class, food eating habits, the hierarchies of organisation and the dynamics in interpersonal contact and relationships, spatial dynamics, students’ extracurricular interests and hobbies, their deeper aspirations, all point to the conflict between the school’s ideals linked to a Victorian past emphasising the ‘nation’ in progressivist and affirmative terms and a contemporary popular culture, selectively ‘global’ and in which the nation is a problematical, if not a fully subdued category. Principally, the films, in the context of India as a social democracy reference how a feudal and colonial past constantly co-mingles first with the residue of institutionalised socialism and the more recent, aggressive capitalism heralded by the economic liberalisation of 1991. This introduces to us a particular identity dynamic whose logic is formulated through the pulls between social-functionalism and consumerist-individualism. Mapping the convergence of these competing socio-cultural imperatives on the bodies of the students serves as a historical commentary and catapults the films from a wilfully preservationist recording towards a more critical and discursive stance in which our engagement pertains to how dominant and ruling ideology shapes and informs subject world-views.

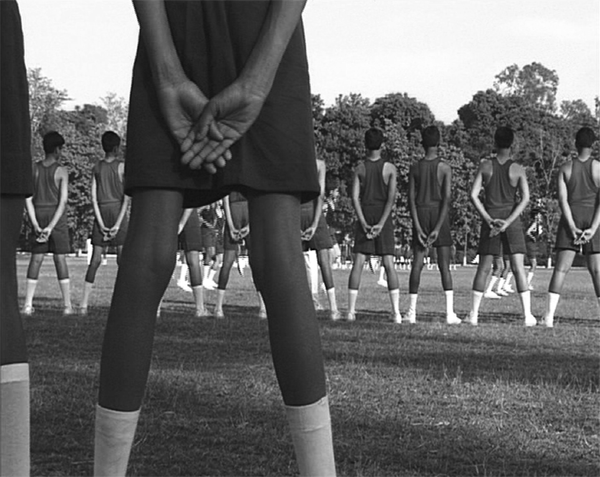

David MacDougall, Doon School Chronicles (2000)

The nationalist project and the implication of youth bodies in it has been a subject of the parallel Indian cinema starting with figures such as Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. MacDougall is touching upon similar issues as the Indian avant-garde but his observational approach is distinct in that it does not in any way tap into India’s aesthetic discourses. MacDougall’s is a phenomenological approach emphasising the sense of being evoked in relation to space as socio historical category. Space is not merely location but is a more ecological and interactive complex. In his words:

… the appearance of a people and their surroundings, their technology and physical way of life; their ritual activities and what beliefs they signify; the quality of interpersonal communication, and what it tells of their relationships; the psychology and personalities of individuals in the society; the relation of people to their environment—their knowledge of it, use of it, and movement within it; the means by which the culture is passed on from one generation to another; the rhythms of the society, and its sense of geography and time; the values of the people; their political and social organisation; their contacts with other cultures; and the overall quality of their worldview.’ (Nichols 1976: 146)

Tapping into the institutionalised aspects of youth culture, the Doon School films enable us to access and contextualise the factors and symptoms linked to the rising apathy among the Indian middle class – a characteristic that has sharply risen since India’s economic liberalisation. Pavan Varma links the Indian middle-class attitudes in a post-liberalisation consumerist context to a ‘devaluing of idealism, as an aspect of leadership and as a factor in society’, coupled with the ‘erosion of the legitimacy of the State as an effective economic factor’ and the ‘legitimisation of corruption as an accepted and even inevitable part of society’ (Varma 1998: 82). These trends have, according to him, contributed to a decline in concern towards wider socio-political and economic issues such as poverty and inequality. The Doon school films are dotted with instances and conversations through which we access the conflicts and frustrations that result when such a middle-class background encounters the school’s ideals that have not necessarily been revisioned in keeping with the socio-cultural changes percolating Indian society. This is succinctly evident when for example one student suggests how the boarding school is so abstracted from the socio-economic complexities and contours of the ‘real’ world beyond its boundaries. He suggests, in a rather incoherent manner, how such an abstracted context impedes an individual’s relations and interactions with one’s environment. The conflicts in student mindsets are furnished more fully when we repeatedly observe them learning, which is clearly an exercise in rote and its incumbent attitudes.

The male body in a postcolonial context is historicised and problematised in terms of the confliction between and the co-mingling of liberal-consumerist attitudes with the Victorian. Art historian Geeta Kapur, who has deliberated on the distinction in the conception of the body through documentary in India, argues that the ‘contemporary body’ is tightly imbricated with the urban cityscapes and topographies as fashioned by India’s economic liberalisation. She substitutes, for ‘polemical effect’, the phraseology of ‘body-language’ instead of the ‘body’ to draw the disparity between the socio-historical and cultural determination of the body on the one hand, and its conception in more poetic terms. She states that while one alludes to ‘material metonymies that map desire – the fragments ingested, disgorged, relayed to the receptor as a series of signs’, the other bears ‘the pleasure in beholding repossessed bodies, in decoding allegories that spell mortality’ (2005: 107). According to her, ‘The mode of cross-referencing [between body and city] is indexical: the body positioned in contiguous relationship with the city, so that we look for mutual trace and imprint in the body-city interface’ (ibid.). If we combine this proposition with the deliberation on changing cityscapes of India after economic liberalisation, as discussed by Pavan Varma, we are better positioned to appreciate MacDougall’s specific take on the male body that locates in it an urbane and quite aggressive consumerist investment. The intermixing of the Doon school’s zealous vision imbued with nationalist vigour – itself a residue of the colonial era, with a contemporary youth culture implicated in globalisation, define a clearly upper-class and elitist overture that is at far remove from India’s little, folk, and classical traditions as nativist alternatives.

David MacDougall, Doon School Chronicles (2000

Since his early films in India, including Photo Wallahs, the duration of the shot in MacDougall’s films has steadily increased. This is a crucial and critical strategy that facilitates observation – the viewer’s relationship to the image is open-ended as the camera deliberates upon and maintains distance from subjects. MacDougall’s cinematography is not indexical, instead it invites the viewer to scan the field of vision and engage with his ruminations. His essayistic style privileges putting subjects and their actions in the context of space as a historical and sensorial construct. The viewer is allowed to engage with aspects of human subjectivity that are not readily or tangibly available through performed and spoken discourse but only suggested through body gestures, postures, conduct and codes of dress. In this process the authorial imperative is not fully determined or authoritarian and neither is it effaced. Schoolscapes (2007), the film surrounding J. Krishnamurthy’s Rishi Valley school is edited as a compilation of single shot scenarios – entire scenes performed in a single shot. Here MacDougall takes us back to early cinema and reinvigorating the primitive mode of representation as discussed by Noel Burch (1981). The early cinema aesthetic is evoked at two levels in Schoolscapes. The single shot scenario is an explicit reference to single shot early films, prior to the use of editing and intercutting that emerged around 1904. In his lecture accompanying the screening of Schoolscapes at the Royal Anthropological Institute’s Ethnographic Film Festival 2007, MacDougall had stated that Schoolscapes is inspired by early cinema techniques particularly the Lumières’ single-shot films. MacDougall’s single-shot scenarios in Schoolscapes are however distinct from early cinema’s tightly structured narratives. They do not contain any explicit or causal narrative – they are principally observational and evocative of spatial constructs and textures and how those link with the bodies. Due to this the viewing experience is of a different order as narrative is thinly constructed and so engagement is largely at the level of discourse.

David MacDougall, Schoolscapes (2007)

The sustained shots with sparse camera movement reflect a highly evolved rapport between ethnographer and his subjects. The films are dotted with rich instances where a relationship between MacDougall and different subjects is forged and performed through the film process – a relationship that extends towards a more humane and expressive dimension. Through this MacDougall references key elements of Krishnamurthy’s philosophical discourse emphasising relationship as the structuring principle of human experience and contemplation. A more critical and complex approach to documentary emerges that exceeds social-functionalism, which dominates documentary practice in the subcontinent. The element of relationality in MacDougall’s work makes documentary as an evocative and creative practice bearing a phenomenological dimension that serves to decentralising the source of meaning and emphasis. This is not only useful in the context of problematising documentary in a post-colonial framework, but more broadly for interrogating the truth and scientific claims underpinning documentary as a discipline. With regard to this, Bill Nichols observes:

It may be no coincidence that both David MacDougall and Alison Jablonko envision an experiential or perhaps gnosiological, repetitive, poetic form of filmic organisation that would foster ‘haptic learning, learning by bodily identification’, or would replace subject-centered and linear models with ones ‘employing repetition, associative editing and non-narrative structures’ … Efforts such as these would move away from attempts to speak from mind to mind, in the discourse of scientific sobriety, and toward a politics and epistemology of experience spoken from body to body. Hierarchical structures designed for the extraction of knowledge (the interview, the informant, the case study) might yield to more fully personal, participatory encounter that makes an expansion or diffusion of the personal into the social and political inevitable… (1994: 82)

At a further level, MacDougall develops a highly evolved haptic visual regimen, which is also characteristic of early cinema. Sustained images from competing angles disassemble a centralised humanist perspective. The sense of touch and texture emerges as the principle register for visual engagement. MacDougall’s films reveal a proximity to Vertov’s kino-eye with its extensive range of camera angulations. Dramatic foregrounds, with carefully deployed close-ups and depth-of-field enable us a viewing position in which the subject within the frame, animate or inanimate, assumes a corporeal and embodied presence. It is pertinent to qualify here that MacDougall’s use of depth-of-field and close-ups exceeds the conventional understandings of these as discussed in film theory – the former contributing to the realism effect in keeping with Bazinian realism and the latter contributing in detail or emotion. For MacDougall the sense of vision is not physical or objective serving a corroboratory or informational function only. It is as he points succinctly in the introduction to The Corporeal Image, co-extensive with the experience of being. He says:

Our consciousness of our own being is not primarily an image, it is a feeling. But our consciousness of the being, the autonomous existence, of nearly everything else in the world involves vision. We assume that the things we see have the properties of being, but our grasp of this depends upon extending our own feeling of being into our seeing. In the process, something quintessential of what we are becomes generalised in the world. Seeing not only makes us alive to the appearance of things but to being itself. (2006: 1)

MacDougall’s images serve a sensorial function for the viewer extending the experience of film viewing into experiential realms exceeding visually verifiable narrative or information. Consequently while MacDougall’s documentaries deploy the camera’s capacity to record, his approach is more complex in that it facilitates in extending engagement with subjects to the realms that exceed words and physical or objective actions. Film viewing is extended into a corporeal direction wherein vision and viewing do not purely serve an evidential function. Instead the haptic visual regime is principally evocative. Here evocation is not of the order of bias, but a sense of nearness and touch both as a tactile encounter as well as a humane gesture that defamiliarises commonsense reality:

For MacDougall, this evocative potential seemed linked to a potential shift in epistemology, or at least a radical reconceptualisation of the terms and conditions of ethnographic film so that it would no longer be seen simply as a colourful adjunct to written ethnography but offer a distinct way of seeing, and knowing of its own. But MacDougall does not insist on this rupture. There is the lingering sense that the texture of life contributes to an economy and logic that are still fundamentally referential and realist. MacDougall also evokes a generic oneness (‘the overall quality of their worldview’) which leaves the position, affiliation, and affective dimension of the filmamker’s own engagement to the periphery. Performative documentary seeks to evoke not the quality of a people’s worldview but the specific qualities that surround particular people, discrete events, social subjectivities, and historically situated encounters between filmmakers and their subjects. The classic anthropological urge to typify on the basis of a cultural identity receives severe modification. (MacDougall’s own films exhibit these performative qualities, to a greater extent than this quote, and may attempt to persuade traditional ethnographers to give greater attention to film but in a way that leaves traditional assumptions essentially intact.) (Nichols 1994: 101)

The presence of the camera and the haptic visual regimen registers the students’ rapport with MacDougall and in turn references the experience of space in sensory terms. The verbal conversations and gestural exchanges between MacDougall and the students extend the filmmaker as socialised being. The particularity of the observational mode is that it does not privilege a specific code or set of coda as the coherent and normative mechanisms for developing a reflexive or deconstructionist approach. The observational mode is a critical practice that disrupts received relationships within the social field. Thus MacDougall’s films present the most clear fusion of the modernist and ethnographic imperatives for self-reflection in terms of inter-subjectivity as socio-historically constituted and uses that as the basis for inviting the viewer into deciphering an ideologically critical stance as opposed to a polemical or didactic posture that idealises or essentialises by abstracting all but formal codes and issues as the means and level for an interventionist practice.

CONCLUSION

A survey of Shahani and MacDougall’s documentaries in India raise for us two interventions. Firstly, they both emphasise the body – the subject and filmmaker – as socio-cultural and historical categories. Much modernist and avant-garde practice overlooks this. Approaching the body as socialised invests in practice in the distinct edge of historicity and cultural specificity, crucial in any representation for resisting universalism. Further, both practitioners present to us alternatives for critiquing dominant ideology. Here it is pertinent to qualify ‘dominant ideology’ not in terms of mainstream cinema, but nationalist ideology – that which the filmmakers encounter in the filmmaking process and context. This is useful because the critical imperatives of both filmmakers extend the notion of a radical and interventionist practice beyond critique of mainstream cinema codes towards context-specific criteria that in the case of both filmmakers pertains to the nationalist rhetoric and jargon of the Indian subcontinent. Both filmmakers emphasise the interrelations and eliciting discourse between filmmaker and subjects as the basis for developing film form. In Shahani this takes shape in his specific use of juxtaposition and the long shot; in MacDougall this takes the form of his conversations with subjects and an evocative, haptic visual regimen. Both filmmakers reconstitute film form within the specific context of the film encounter, their formulations exceed and critique dominant and mainstream cinematic conventions. Film form in their practice emerges as context-specific rather than an ossified category that bears fixed meaning and connotations irrespective of film process or cultural context. In the theory-practice debate within film education, this intervenes by stressing that while dominant conventions necessitate critique and deconstruction, that project cannot be conducted in abstraction and isolation from the filmmaking encounter and process. In this process the filmmaker’s subjectivity is a crucial player and merits equal unpacking as the subject’s socio-historical and cultural context. These aspects cannot be isolated, and are intimately tied to and visible in the formal techniques and processes that filmmakers such as Shahani and MacDougall deploy. Though distinct in disciplinary approaches, both MacDougall and Shahani present to us complex documentary formulations that emulate a critique of nationalist ideology in India and extend through their documentary aesthetics our understanding of film form as implicated with the filmmaking encounter.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Becker, L. And R. Hollis (2004) Avant-Garde Graphics 1918–34. London: Hayward Gallery Publishing.

Burch, N. (1981) Theory of Film Practice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chanana, O. (1987) Docu-Scene India. Bombay: Films Division.

Devereaux, L. And R. Hillman (eds) (1995) Fields of Vision: Essays in Film Studies, Visual Anthropology and Photography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Dunne, J. A. And P. Quigley (eds) (2004) The Montage Principle. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi.

Hayward, S. (2000) Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts. 2nd edn.. London: Routledge.

Jacobs, L. (eds.) (1979) The Documentary Tradition. 2nd edn.. New York and London: W. W. Norton and Company.

Kapur, G. (2000) When was Modernism? New Delhi: Tulika Books.

_____ (2004) ‘Tracking Images’, in M. Nash, Experiments with Truth. Philadelphia, PA: The Fabric Workshop and Museum, pp. 105-111.

Lutyens, M. (1987) The Penguin Krishnamurti Reader. 11th edn. London: Penguin.

MacDougall, D. (1976) ‘Prospects for the pp. 135-150. Ethnographic Film’, in B. Nichols, Movies and Methods – Volume I. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 135-150.

_____ (2006) The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography and the Senses. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Myer, C. (2004) ‘Playing with toys by the wayside: an interview with Noel Burch’, Journal of Media Practice, 5, 2, 71–80.

Nandy, A. (1994) The Illegitimacy of Nationalism: Rabindranath Tagore and the Politics of Self. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Nichols, B. (1994) Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Pines, J. and P. Willemen (1994) Questions of Third Cinema. 3rd edn. London: BFI.

Rodowick, D. N. (1994) The Crisis of Political Modernism: Criticism and Ideology in Contemporary Film Theory. Berkeley, CA and London: University of California Press.

Rosenberg, D. (2000) ‘Video Space: a Site for Choreography’, Leonardo, 33, 4, 275–80.

Shahani, K. (1986) ‘Dossier – Kumar Shahani’, Framework, 30/31, 80–101.

Sharma, A. (2007) Montage and Ethnicity: Experimental Film Practice and Editing in the Documentation of the Gujarati Indian Community in Wales. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Glamorgan.

Seale, C. (1998) (ed.) Researching Society and Culture. London: Sage.

Sherman, S. (1998) Documenting Ourselves: Film, Video and Culture. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Stam, R. (2002) Introducing Film Theory. London: Blackwell Publishing.

Varma, P. K. (1999) The Great Indian Middle Class. New Delhi: Penguin.

FILMOGRAPHY

Apu trilogy (1955–60) Directed by Satyajit Ray [DVD]. Amazon: Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment.

As the Crow Flies (2004) Directed by Kumar Shahani [Film]. India: Immanence.

Bamboo Flute, The (2000) Directed by Kumar Shahani [Film]. India: Immanence.

Bhavantaranaa (1991) Directed by Kumar Shahani [Film]. India: Immanence.

Choreography for the Camera (1945) Directed by Maya Deren [DVD]. Amazon: Mystic Fire Video.

Doon School Chronicles (2000) Directed by David MacDougall [DVD]. Berkeley: Berkeley Media LLC.

Photo Wallahs (1992) Directed by David and Judith MacDougall [DVD]. Berkeley: Berkeley Media LLC.

Schoolscapes (2007) Directed by David MacDougall [DVD]. Berkeley: Berkeley Media LLC.