I start off wanting a film to be good. Then problems start and all I can hope is that we finish. I take myself to task – ‘You could have worked harder: still you have some time left.’

– La Nuit Américaine (François Truffaut, 1973)

François Truffaut, himself acting the role of a film director in a film about filmmaking, muses in voice-over whilst fighting to keep his film afloat in La Nuit Américaine (Day for Night). The film is amusingly and painfully accurate about the difficulties of filmmaking and the mountain to be climbed in order to achieve a creative result. The vicissitudes of chance, of personal life intruding on the film, of the money men refusing to back the project, have to be negotiated and Truffaut’s solution is finally that of creativity. His response to the travails of filmmaking is to ‘try to make the film come alive more vividly’, and this he does, at the cost of the death of one of his lead actors, Alexandre (played by Jean-Pierre Aumont). This chapter is about the difficulties, inhibitions and necessities of such creativity, and the ways that this might be understood and taught. In film schools, university departments, and art schools, students are busy making films, working under very different circumstances to those of Truffaut in his professional filmmaking. Nevertheless, I will argue that through the pressures of no-budget, strict-schedule filmmaking students hoping to find their voice and achieve their grades have travails that are in some ways equal to those of Truffaut in La Nuit Américaine. I suggest that we, as teachers, understand these pressures and have ways of countering them in order to foster student creativity. In Augustine (Houtman 1993), my graduation film from the National Film & Television School, I told the story of a hysterically mute girl committed to the asylum at La Salpêtrière and treated by the famous neurologist, Jean-Martin Charcot, who eventually finds her ‘voice’ and breaks out of her captivity. This was an expression of experience at film school finding myself traumatised by the demand to ‘speak’ creatively, to perform the discourse of filmmaking in a context where it seemed that my career (and future life) depended upon critical and popular success. Since teaching, I have found that this specifically creative trauma is far from being unusual or unique to me. The aspiring filmmaker is in a highly competitive environment where it is very easy to be seduced by narcissistic identification with the rewards of the media industries and become devastated by the failure to develop the skills and competencies which enable a ‘speakability’ within this environment. I shall suggest that it is possible to develop what I shall call ‘Authorship skills’ – that is critical and reflexive skills which are directed towards the understanding and expression of desire and the finding of ‘voice’. Using these skills the student may find the ability to value their own creativity, to find ways of expressing it and thus to develop strategies against trauma.

What are the ways in which we might enable voice and agency in filmmaking? One way would be to take postmodern concepts of authorship seriously and structure our teaching accordingly. This is, happily, partly already happening by default, as we teach larger numbers. We increasingly encourage group work and teams rather than individuals. However, if authorship is no longer seen as an individual act of creation or origination, but as an inevitable and often non-voluntarist performance of the self, spoken by and speaking discourse, then we can both enable a more playful inhabiting of the role of filmmaker and also encourage our students in the study of film and culture generally, in order to foster their intertextual performativity. We can encourage them to find signifiers for their desire and become aware of those barriers which restrict them.

In the beginning of La Nuit Américaine the actors are interviewed by paparazzi about their roles in the film, and they all come up with different interpretations of the script. This is the postmodern concept of the instability of discourse, made visible. It is the job of the director, (in this case, Truffaut as a character within the drama and also as director of the actual film) during the filming process, to marry these different interpretations into a satisfying whole without reducing the film to a lifeless schema, and to communicate this consensual writing, to the audience acting as consensual viewers. By the end of the film, by utilising what I would pragmatically call ‘the creative use of compromise’ or, in other words, by performing the discourses which surround the film making process – the collaboration of crew and cast in the face of events beyond their control, he makes the best of things, and finds the film that incorporates meaning in the most rich way possible. He brings death back to creative life, by shooting a scene in the snow to recreate a dead actor, and even incorporates the real life words of his British lead actress, Julie Baker, played by Jacqueline Bisset, into the dialogue, to explain the motivation of her character. How do we teach such creativity to our students?

I have two main suggestions for helping students to find their filmmaking potential. These are not necessarily new suggestions or even surprising. The first suggestion is very directly about the importance of theory to practice. By offering our students a choice of conceptual frameworks, a lively and iterated sense of cultural history and theory, we free them from the slavish adherence to models of film-making, models of seeing the world which only allow of one perspective, one technology. It is our contextual knowledge, as teachers, which enables us not to fall into binarised or reductive thinking, of trying to make students’ ideas fall into our templates, but recognising that original ideas can come from many different traditions and that we know how to weigh one tradition against another and to use whatever technique is productive for the idea. Thus, as teachers we constantly relate the new speech to its intertext and interrogate it to discover its own production of meaning. Students learn from our example as skilful practitioners of theory and of practice, that filmmaking and contextual thinking are intimately related skills and that each broadens the potential of the other. In such a rapidly changing media world, conceptual skills are vital in order to create an energised and inhabited sense of ‘craft’. For example, in the world of writing, then having postmodern ideas of the writerly text, as explored by Barthes (1977: 142–9) and of the postmodern authorial subject,1 enables us to give our students confidence against the rather ubiquitous Hollywood Aristotelian ideas of script, without junking the insights of Robert McKee (1999) et al. completely. Instead we may ask ‘What does having a character led film mean?’ in a world where subjectivity is defined performatively, or psychoanalytically, or ‘What does it mean to organise a three-act structure with inciting incident on page 23’, and so forth, where meaning is unstable and contains the seeds of its own chaos. Indeed we may look at the instabilities of our students’ films and in them find what it is about them that is revealing, meaningful despite itself. Deconstruction as an act of textual criticism has become regarded in some circles as passé, whereas deconstruction as an act of script development has always been important and should certainly be part of current practice. We may then return to the Aristotelian comforts of character catharsis and closure by appeal to myth and to the functions of identification desire and empathy in fiction, but we will be returning informed and fresh. By interrogating the basic tenets of drama, for example ‘What is action? What do people do to each other?’ we are then able to rearticulate and reinvigorate basic dramatic questions for our students and enable them to come up with their own answers. Furthermore, finding correspondences, ‘this work resembles the plays of Strindberg’, or ‘this film works with an oblique sense of character and point of view like the films of von Sternberg’, or ‘this film has a feminine/ feminist aesthetic’, allows us to help situate our student ‘authors’ as spoken by discourse and yet inflecting it differently. The students need not be placed in the invidious position of having to produce ‘originality’ from nothing. The craft skills of writing may, hopefully, engage with the narrativity of our current lives so that they are the skills of the current and the future media industries and arts. Personally, I do not feel it is acceptable any more to populate the academy with expertise in only one kind of writing, or one form of industrial production, however deeply imbricated and skilful this expertise might be, unless a lively critique is also available to situate this work and to suggest alternatives. However, we do, like Truffaut, need to enable our students to pick the version most appropriate to their film and give them the courage to see it through.

The kind of approach to discourse outlined above is illuminated if we see it through the filter of Lacan’s Discourse Theory as discussed by Paul Verhaeghe (1995). Lacan has a model of communication of how we are performed by discourse and in particular, how both our conscious and unconscious statements are positioned in regard to the other of our address. Lacan’s Four Discourses were designed primarily as tools for understanding the process of the psychoanalytic session. They comprise a model of how analysts and analysands may take up different subject positions in the session and how these positions illuminate both what is being conveyed through the communication between analyst and analysand and also what is being repressed, what fails to be communicated, and what is at stake for the individuals communicating in this particular way. The Four Discourses also enable a political analysis of the act of communication between two people and of the relationship between that and the psychoanalytic condition of a particular individual. They can therefore be applied in all circumstances, not just that of the psychoanalytic session. The discourses comprise the four types of social bond which can and are taken up by all people at some time. They do not indicate pathological conditions, but rather tendencies, particular approaches towards others, towards oneself, and towards knowledge, which may be weighted in particular individuals towards one discourse rather than another. The Four Discourses are the Discourse of the Master, the Discourse of the University, the Discourse of the Hysteric, and the Discourse of the Analyst.2 One of these, his Discourse of the University, actually accounts for what I have been talking about when I have argued about the necessity for a fluid and pluralist approach to conceptual frameworks and contexts in film work.

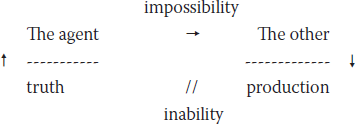

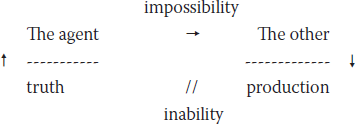

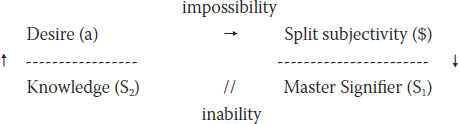

The basic model is of the speech act, so in all Four Discourses, on the left, we have the agent or speaker and on the right the other or receiver.

Underneath the bar on both sides is a repressed element, so that the agent/ speaker on the left is motivated by some truth, under the bar, which when introduced to the other as unconscious communication leads to a production, under the bar on the right. The qualities under the bars cannot communicate directly as they are the unconscious of the communication. In each of the Four Discourses, these basic terms are also filled by other qualities which are superimposed upon them. Lacan provides terms which he has developed elsewhere in his theories which are superimposed upon the equation always in the same order, but starting from different places in the equation. The terms are:

S1 = the Master signifier

S2 = knowledge (savoir)

$ = the subject

a = surplus enjoyment

In each Discourse different terms are placed in the position of repressed truth, and in the place of production, in the place of the agent and the other, and therefore there are different places for impossibility and inability, different aspects of discourse get repressed or fail to be communicated within the different Four Discourses.3

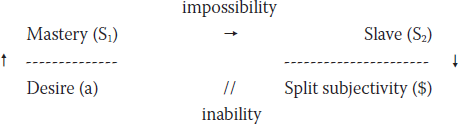

Thus, in the Discourse of the University, the following equation is superimposed on the basic model:

If the student filmmaker is in the position of Agent, and Mastery is below the bar, then this mastery is (a) their knowledge of filmmaking, (b) their reflexivity upon their act of filmmaking which can justify it in historical/contextual/ aesthetic terms, or (c) the Academy justifying or contextualising their effort. On the right is their film, the object of their desire, and hidden underneath the bar is what Elizabeth Bronfen calls their ‘knotted subjectivity’ (1998: 8–12), i.e. all the influences, conscious or unconscious which speaks and misspeaks them. Thus, the successful Discourse of the University produces a film, but also the knowledge of the student that they are fallible, that they are humble in the face of discourse.

In La Nuit Américaine Truffaut comments that the director is ‘someone who is being asked questions all the time. Sometimes he knows the answer, sometimes not’, and the film shows Truffaut and his collaborators finding the answers to any number of questions throughout the film. Here, the Discourse of the University speaks in both directions – the crew as Agent with Truffaut as Desire, and vice-versa. The crew need to know what Truffaut wants, and they interrogate him for the answers, which he produces. This is reversed when he does not know how to do something, for example, deciding on what to reshoot after Alexander’s death. Sometimes, the answers come by the process of the Discourse of the University so that, for example, when a cute cat fails to perform properly and lick some milk left in a discarded breakfast tray, the make-up girl remarks to the props man that they should have had a replacement cat, an operation of the Discourse of the University in that it emanates from the make-up girl’s superior knowledge and experience. Truffaut as a listener is also operating within the Discourse of the University; his openness to suggestions is the mark of a good and experienced director who is prepared to find answers wherever they appear – although it is probably also a mark of desperation in the face of the seemingly impossible. The Discourse of the University, as I have already outlined, also operates through any directorial interpretation of script which is based on sound methodological basis. The ability to make decisions based on an understanding of relative conceptual frameworks is a skill that the University is ideally suited to teaching, and we are able to give our students an understanding of character interpretation, or understanding of the structural importance of a scene, supported by textual and historical knowledge, is an imperative for their creative work. Enabling our students to have a broad understanding of where their scripts are going and what is important about them will enable them not only to choose what to include, but like Truffaut, to choose what they do not need to shoot, and how contingencies may be met.

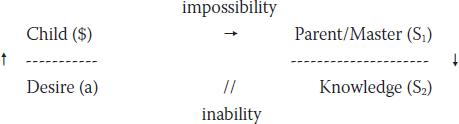

However, sometimes Truffaut’s directing decisions are made just so that a decision has been taken, for example, when he is choosing props or cars, items that have no structural implications for the script. At these moments, Truffaut is operating through The Discourse of the Master where the positions have all rotated by 90 degrees:

Truffaut has to make a decision, otherwise filming would stop, and therefore any decision is better than none. Lacan’s prime example here is of Churchill during the Second World War, who needed to be followed, but whose decisions were made out of seemingly impossible and doomed situations, and in the dark. This is the role of a leader. The paradox here is that experienced directors know this, and know that giving orders or making decisions is actually their job, and this therefore also falls into Discourse of the University, as established practice.

La Nuit Américaine, although a European art film is far from being introspective – Truffaut is a figure of action and we actually have little access to his decision-making processes, indeed we get to know him very little (his occasional voice-over sums up, gnomically, general theses about filmmaking, not his motivations whilst making this particular film) – and therefore it’s not easy to see the hidden terms of the discourse lying under the right hand bar of Lacan’s equations or what they produce within the film. Yes, we can see that as Truffaut or his filmic family solves each arising problem operating under The Discourse of the University: he is led by desire onto the next (the Desire (a) on the top right of the equation) but we don’t see the split subjectivity ($) hidden underneath it. However, we do see the result of these discourses on the crew obeying Truffaut operating The Discourse of the Master. Their love affairs and petty rivalries are the repressed subjectivities returning not in the filmmaking process, but in their personal lives and in the compressed spare time surrounding the film.

The Discourse of the University and the Discourse of Mastery together produces an end product. Nevertheless it is not possible to operate solely within these discourses in order to produce or create a product. This is because the Discourses of the University and the Discourse of the Master as we have seen, hide or repress any unconscious subjectivity and therefore they are the pure iteration of discourse. Iteration without change is an impossibility, language is inherently unstable. Judith Butler, in her work on performativity, suggests that agency is the space between our interpellation and therefore constitution as subjects through language and societal frameworks, and our inability to iterate these frameworks. We are both ‘spoken by’ and ‘speakers’ of discourse:

The speaking subject makes his or her decision only in the context of an already circumscribed field of linguistic possibilities. One decides on the condition of an already decided field of language, but this repetition does not constitute the decision of the speaking subject as a redundancy. The gap between redundancy and repetition is the space of agency. (1997: 129)4

In other words, the creative film is the product of the failure of iteration. For this filmmaking has also to operate under Lacan’s other two discourses, and will always operate under these, as our subjectivity is always implicated, and this is where my second suggestion for teaching the techniques of ‘authorship’ becomes important.

As well as offering students conceptual frameworks and skills in mastery and knowledge acquisition, I believe we need to treat their desires and unconscious seriously. Thus, my second suggestion is that we train our students in emotional literacy, so that cognitive and emotional skills go hand in hand. Part of this would just be to create a container5 for them so that their trauma is not too great so as to inhibit their functioning. This is possible, partly through our operations of The Discourse of Mastery and the University, where we lay out strict ground rules to give them security, but ones based on fairness, and therefore knowledge. Here, the producer in La Nuit Américaine fulfils this function; using the Discourse of the Master, he calmly controls the money and tells it ‘how it is’, forcing Truffaut to make changes to get the film shot. He shows that actions have consequences, yet he nevertheless supports Truffaut.

However, holding our students is not enough. We might have very happy students, but not necessarily very productive ones. Jean Laplanche called trauma ‘the enigmatic message’ (1998: 265), by which he meant that trauma is that message/signifier which we cannot understand or integrate and which passes from the past to the present and back again, being constantly reinterpreted. The creativity of making something from nothing, of making a film, involves just this engagement with trauma, as Truffaut so exquisitely demonstrates. We have to ask our students at some point to engage with the nothingness of creativity, the blank page, and they have to be supported in their coping strategies. At the University of Wales Newport we always start the first year course with a self-portrait project. We expect them to interrogate their history and make sense of it. This, at some level, aims to promote a helpful engagement with the student’s hysteria, and therefore their own personal investment in the knowledge that they learn. This may be achieved in two ways. The first, and perhaps the most creative, is again, part of the holding technique. If we set the students strict boundaries, i.e. production briefs and so forth, we are bound to produce hysteria and rebellion in them. This is where the use of Lacan’s Discourse of the Master, where the imposition of our will creates inevitable backlash, repressed under the bar on the right ($). It is different from the Discourse of the University because it actually demands the students to obey, without having to give an explanation. We impose our hidden desire on our students to perform and their knowledge is supported by their split subjectivity, their own hysteria, revealing their own questions and doubts about our authority. They engage with trauma through a symptomatic or rebellious defence against it, often a productive defence.

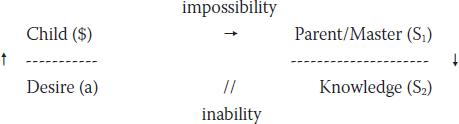

If the student becomes hystericised through our exercise of the Discourse of Mastery, then they cannot settle on a fixed identity, they cannot fall back on cliché or convention. However, this may provoke another 90 per cent turn so that they become agents in the Discourse of the Hysteric:

This posits the student filmmaker as a child at the Oedipal stage in the symbolic encounter with society and makes them ask what Lacan called the hysterical questions ‘Am I a Man or A Woman?’, and ‘Am I Alive or Dead?’ They are trying to find out from us, as surrogate parents, the secret of our desire, in order to conform to it. Alphonse (played by Jean-Pierre Leaud, Truffaut’s long term surrogate from his autobiographical films) is the character most operating under the Discourse of the Hysteric within the film. He is hystericised by not feeling able to act well in the film, then by Julie Baker sleeping with him and subsequently rejecting him, and he then applies the discourse himself, cruelly trying to break up Julie’s marriage by revealing her adultery to her new husband. He acts exactly like a child with no parental boundaries in a difficult situation. Whilst it might not be possible to change his behaviour, it is the responsibility of Truffaut to control it, something he fails to do, and this is his failure of responsibility. Film Schools also have their responsibilities; they must often act as arbiters between students, making sure that their students pull their weight in their production teams, and that there is no favouritism or bullying. However, this is harder to achieve with large class sizes and limited resources. Nevertheless, Film Schools often act as primal parents, themselves acting under the Discourse of the Master - not telling students what they want from them, but making plain their unconscious desire, which is that the students should be a) creative geniuses, b) make lots of publicity and money for the school c) not cause trouble or appear to fail in attendance – in summary be a success and produce something new from nowhere. This is the bad side of film schools and the side we should try to avoid, by being clear, and also by understanding our own unconscious motivations to force the productivity of our students. The Master, also, too often degenerates into a primal figure, inhibiting the students through powerful super-egoic constraint. It is not enough merely to discipline students, I think we need to love and nurture them. Too often, the Master offered to film students and filmmakers is a masculine one. The teacher, the film director as father, and this, in my personal experience, has been more frequently foregrounded, with less than perfect results for those women who wish to enter filmmaking. We need a mother figure as well as a father, in order to establish a more properly Lacanian symbolic triad. Thus the lecturer holds the students and the institution creates a symbolic which is not arbitrary but consensual. With increasing student numbers and financial pressures, and with the complexity of film practice courses, this does not always happen, and I believe we cannot have a successful student community without a functioning academic body within the discipline as such and within individual institutions. Here, the historical dysfunction between film theory and practice and between theoreticians and practitioners can hardly be doing our students any good.

None of Lacan’s Four Discourses are either good or bad, but have both good and bad consequences. The helpful part of The Discourse of the Hysteric is that it promulgates healthy rebellion. Handled carefully and with the other discourses it can create a fertile intextual relationship between rules of genre and its performance. In La Nuit Américaine the poor prop man, faced with the knowledge that he should have produced another cat, trapped by the situation ($), a moment where split subjectivity comes into the open, expressed as hysteria, uses this to gain a closer access to the make up girl who he desires. The lead actress, traumatised by the death of her male co-star, produces the dialogue that enables the film to be successfully completed. Surely, film education must have some element of this, to force students into really committing their subjectivities to their work. For me, this is through our operation of the Discourse of Mastery with as little hysteria as possible. Hysteria is an inevitable part of the production process, and we do not need to increase it with our agency as teachers. Rather we need to manage it and hold the students so that they can place their insecurities within a solid framework.

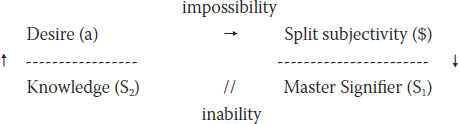

The Discourse of the Hysteric provokes the agent/film-maker into a confrontation with their own trauma and sometimes a resolution where they reinterpret the trauma in the light of their current understanding. Thus the Discourse has to be entered into in order for a psychoanalytic subject to achieve a ‘working through’. In the psychoanalytic session, therefore, the analyst may need to provoke the patient’s hysteria in order to make them reassess their behaviour and bring them to a more pertinent self-understanding and self-narrative. In filmmaking, this is exactly what we need to do with students and their scripts. We need to make them discover what it is that drives their scripts. We encourage them away from convention and towards the expression of experience and of imagination. Thus we may need to provoke their hysteria in order to resolve it. However, in provoking them into the Discourse of the Hysteric, there is a danger that we ourselves accept our role as Master and tell students the answers to the questions of their desire. This is terribly dangerous as we cannot know this and we will only provoke them to overthrow us as Masters. Instead we must show them how to find their identity. This is the Discourse of the Analyst:

Thus, the teacher in the position of Agent addresses the student in their split subjectivity, and offers them a set of interpretations which enables the student to discover their Master Signifier, i.e. what is driving them. In La Nuit Américaine this is actually what Julie (Bisset) does for Truffaut. In talking, she presents him with what he needs for his script. He is then able to continue. He also does this for her. When she is hysterical with grief at the supposed failure of her marriage, he gives her what she most wants – the illogical and nonsensical object of desire (a), the pat of butter. As teachers, we do this for students through our feedback processes, on their scripts and their films. By a simple, almost Socratic method, we can read their scripts and interpret back to them how the scripts are producing meaning, but we must do this, not just through the Discourse of the University, but also through the Discourse of the Analyst, listening to the students’ desire expressed in their scripts and in what they say about them. The question ‘I understand the script to mean this, is this what you want?’ is how we might approach a student’s work. It is for this reason that we need subtle and complex frameworks, like a psychoanalyst, to register what is lurking latently within the script as well as its attempt to fulfil a brief or conform to a template. I am not at all in favour of psychoanalysing students or subjecting them to obtrusive personal investigation. This would not be treating them as subjects spoken by discourse. Instead, what I’m suggesting is that we treat the work, the film, in this way. It is this performance which needs to be subjected to such an analysis, and then referred back to the student. This way we enable to the student to find their Master Signifier, what they need for the film to work. Of course, in encouraging the exercise of filmmaking authorship we would be encouraging the students’ ability and independence to become adept at this practice both within their own work and in their work with others, as crew, as fellow critics, as friends. The sophisticated filmmaker engages with this practice as central to their filmmaking, whether they are conscious of it or not. Our encouragement of this ‘Authorship’ skill within the Academy is central, and I believe should be our core skill, carried out through an iterated practice of close textual analysis of all kinds of films and texts, not just student texts, so that students can see that all filmmaking is governed by the same activity.

The Discourse of the filmmaker is thus like the practice of the analyst. We must place our desires on the line, supported by our knowledge of film practice, theory and history, and use this to find a Master Signifier, in our textual palimpsest (our working copy of our film) and then we can use this understanding and connection to meaning in order to make a film which communicates.

The danger in the way I have been talking about authorship skills as discursive performativity is that this is too easily misunderstood to mean that the surface of communication means everything. When training filmmakers we need to arouse their imaginations bodily and experientially and we can only engage with their feelings and desires if we do so. Teaching students filmmaking only from a text based approach is like being an actor who only acts from the neck up. Nevertheless, Lacan’s insight is to treat these emotions, these bodily experiences, as imbricated and bisected by language, made meaningful by language, and this again enables us to find a conceptual framework within which to work with emotion, experience and performance.

At the end of La Nuit Américaine, one actor is dead through an accident. The love affairs created on the film go wrong and Alphonse betrays Julie through The Discourse of the Hysteric when he phones her elderly husband to tell him about their one night stand. He tries to destroy the filming process and almost succeeds, yet goes on successfully to star in other films. His primal influence is negative, and perhaps it is not our job to teach students not to be primal. Yet, our example should enable them to surmount the hysterias that beset filmmaking, and enable the ‘family’ of the film to be a functional and a ‘good enough’ team. Yet, at the end of the film, one of the actors is dead, lost through the process of filmmaking – he is killed in a road accident provoked by hard work and the film impinging on his personal life. Surely, this shows us that filmmaking is all about loss, and about making good this loss. The action of the therapist and the therapeutic relationship is frequently to accomplish the act of symbolic castration, so that patients understand the nature of trauma and loss, and accept it. Anything we can do to treat our students work likewise will enable them to create a fictional world that repairs their psychic world, and this is surely to be desired.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barthes, R, (1977) ‘The Death of the Author’, in Barthes, Image-Music-Text. Glasgow: Fontana, 142–9.

Bronfen, Elizabeth (1998) The Knotted Subject: Hysteria and its discontents. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 8–12.

Bowie, M. (2000) ‘Psychoanalysis and Art: The Winnicott Legacy’, in L. Caldwell (ed.) Art, Creativity, Living. London and New York: Karnac Books, 11–29.

Burke, S. (1998) The Death and Return of the Author: Criticism and Subjectivity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Butler, J. (1997a) Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. London: Routledge, 129–33.

_____ (1997b) The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. California: Stanford University Press.

Lacan, J. (2007) D’un Discours qui ne Serait pas du Semblant. Séminaire XVIII, Paris: Seuil. 1970–1971.

_____ (2001) ‘Radiophonie’, in Autres écrits. Paris: Seuil, 1970, pp. 403–448.

_____ (1999). Encore. Séminaire XX, Paris: Seuil,1972–1973, pp. 1–135.

_____ (1991) L’Envers de la Psychanalyse. Séminaire XVII, Paris: Seuil. 1969–1970, pp. 1–246.

Laplanche, J. (1998) ‘Notes on Afterwardsness’, in J. Fletcher (ed.) Essays on Otherness. London: Routledge, 265.

McKee, R. (1999) Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York, London: Methuen.

Rose, J. (1998) ‘Negativity in the Work of Melanie Klein’, in J. Phillips and L. Stonebridge (eds) Reading Melanie Klein. London: Routledge, 126–59.

Segal, H. (1991) Dream, Phantasy and Art. London: Routledge.

Verhaeghe, P. (1995) ‘From Impossibility to Inability: Lacan’s Theory of the Four Discourses’, The Letter, 3, Spring, 76–100.

FILMOGRAPHY

La Nuit Américaine (1973) Directed by François Truffaut [DVD]. Amazon: Warner Home Video.

NOTES