THE SEARCH FOR THE SOURCE

My quest to understand the importance of the Book of Enoch began with the man who single-handedly revived the scholarly world's interest in this previously lost piece of Judaic religious literature. His name is James Bruce of Kinnaird, and in 1768 he left England en route for Abyssinia, modern-day Ethiopia, in search of something, and it was certainly not the source of the Blue Nile, as he claimed at the time.1

Bruce was a Scottish nobleman, a direct descendant of one of the most powerful families of Scottish history. He was also an initiate of Freemasonry,2 which in Scotland could trace its roots back to the so-called Rite of Heredom, first instituted in early medieval times and later incorporated into the Royal Order of Scotland.3 This in itself was a chivalric military order of honour and valour founded on the rites of the Knights Templar by James Bruce's own illustrious ancestor, Robert the Bruce, following the celebrated defeat of the English at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314.4 James Bruce himself was a member of the Canongate Kilwinning No.2 lodge of Edinburgh, known to be one of the oldest in Scotland, with side-orders and mystical teachings entrenched in Judaeo-Christian myth and ritual.5

Freemasonry is an organization with innumerable secrets, and many of these would have been known to the extremely knowledgeable James Bruce. For instance, he would have been aware that in Scottish Masonic tradition the patriarch Enoch, Noah's great-grandfather, was looked upon as one of the Craft's legendary founders, since he was accredited with having given mankind the knowledge of books and writing and, most important of all to Freemasons, to have taught mankind the art of building.6

Enoch had many associations with early modern Freemasonry, or speculative Masonry as it is known. According to one legend,7 Enoch, with foreknowledge of the coming Deluge, constructed, with the help of his son Methuselah, nine hidden vaults, each stacked one on top of the other. In the lowest of these he deposited a gold triangular tablet (a 'white oriental porphyry stone' in one version) bearing the Ineffable Name, the unspoken name of the Hebrew God, while a second tablet, inscribed with strange words Enoch had gained from the angels themselves, was given into the safe-keeping of his son. The vaults were then sealed, and upon the spot Enoch had two indestructible columns constructed – one of marble, so that it might 'never burn', and the other of Laterus, or brick, so that it might 'not sink in water'.8

On the brick column were inscribed the 'seven sciences' of mankind, the so-called 'archives' of Masonry, while on the marble column he 'placed an inscription stating that a short distance away a priceless treasure would be found in a subterranean vault'.9 Enoch then retired to Mount Moriah, traditionally equated with the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, where he was 'translated' to heaven.

In time, King Solomon uncovered the hidden vaults while constructing his legendary temple and learned of their divine secrets. Memory of these two ancient pillars of Enoch was preserved by the Freemasons, who set up representations of them in their lodges. Known as the Antediluvian Pillars, or Enoch's Pillars, they were eventually replaced by representations of the two huge columns named 'Jachin' and 'Boaz', said to have stood on each side of the entrance porch to Solomon's Temple.10

What exactly the nine hidden vaults constructed by Enoch were meant to represent is completely unknown. They might well refer to the nine levels of mystical initiation contained in the hidden teachings of the Kabbalah, accepted among the Dead Sea communities. On the other hand, perhaps the legends of the hidden vaults referred to actual underground chambers located somewhere in the Holy Land and constructed to hide sacred objects of importance to the future of mankind.

Walked with God

The patriarch Enoch's legendary status among both Jewish mystics and modern-day Freemasons stems from a very strange assumption. In the Bible, Chapter 5 of Genesis contains a genealogical listing of the ten antediluvian patriarchs, from Adam down to Noah. In each case it gives only their names, their age when they 'begat' their first son, and the age at which they died, with one notable exception – Enoch. In his case, he is twice said to have 'walked with God', an obscure statement elaborated only in the second instance with the enigmatic words: 'and he was not, for God took him'.11 Whatever the writer of Genesis had been attempting to convey by these words, they were taken to mean that Enoch did not die like the other patriarchs, but was instead 'translated' to heaven with the aid of God's angels. According to the Bible, only the prophet Elijah had been taken by God in a similar manner, so Enoch (whose name means 'initiated') had always been accorded a very special place in Judaeo-Christian literature. Indeed, Hebrew mysticism asserts that on his 'translation' to heaven Enoch was transformed into the angel Metatron.12

What does it mean: 'translated to heaven'? As we know, people are not carried off to heaven by angels while still living their life on earth. Either these words are metaphorical or else they need drastic reappraisal. Might Enoch have been simply taken away from his people by visitors from another land who were looked upon as angels by the rest of the community? And where was heaven, anyway? We know it is deemed to be a place 'in the clouds', but did this literally mean somewhere beyond the physical world in which we live?

Once in this place called heaven, Enoch would appear to have made enemies immediately, for according to one Hebrew legend, an angel named Azza was expelled from Paradise – the alternative name for the heavenly domain – for objecting 'to the high rank given to Enoch' when he was transformed into Metatron.13

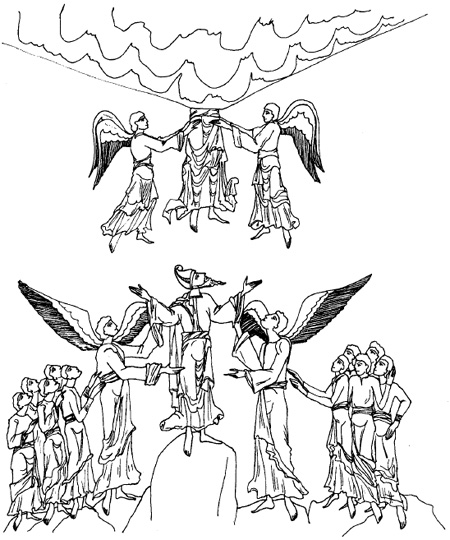

Fig. I. The patriarch Enoch being 'translated' to heaven by two angels, after an eleventh century English manuscript. Enoch was said to have been the first mortal to enter Eden since the expulsion of Adam and Eve after the Fall of Man. Are heaven and Eden ethereal realms of our creation or actual geographical locations in the Near East?

All these legends and traditions concerning Enoch show that the patriarch was highly venerated in Jewish mythology because of his trafficking with the angels. This position led many scholars to believe that apocryphal works, such as the Book of Enoch, were imaginative stories based on his much celebrated translation to heaven, where he now lives in the presence of God.

The Search for the Book of Enoch

James Bruce of Kinnaird was one giant of a man, 'the tallest man you ever saw in your life – at least gratis', or so said one woman who met him.14 He was fluent in several different languages, including some no longer spoken. These included Aramaic, Hebrew and Ge'ez, the written language of the Ethiopian people. Even before his travels in Abyssinia, Bruce had journeyed far and wide, visiting Europe, North Africa and the Holy Land, exploring ancient monuments and searching out old manuscripts ignored by all but a few inquisitive Westerners. In spite of his Blue Nile story, the noble Scotsman would appear to have spent much of his time in Ethiopia within the libraries of ramshackle monasteries, fingering through dusty volumes of neglected religious works, many hoary with age and in a state of advanced disintegration.15

So what had he been looking for?

After nearly two years of constant travelling, Bruce arrived at the sleepy monastery of Gondar, on the banks of the vast inland sea named Lake Tana. Having convinced the abbot of his integrity, he was admitted into the dark, dingy library room, where he found, and was finally able to secure, a very rare copy of the Kebra Nagast, the sacred book of the Ethiopians. It told of a romantic love affair between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, the legendary founder of the kingdom of Abyssinia, and of the birth of their illicit son Menelik, who had conspired with his mother to abduct the fabled Ark of the Covenant from Solomon's Temple. According to the story, the Ark had been carried off to Ethiopia, where it remained to that day.16

Had Bruce in fact been searching for a copy of this obscure but very sacred book to take back with him to Europe?

Despite its rarity, the Kebra Nagast (or 'Book of the Glory of Kings') had long been known to exist, while its wild claims concerning the Queen of Sheba and the Ark of the Covenant were seen by Western scholars as having been concocted to give Ethiopian Christians an unbroken lineage and national identity stretching back to the time of Adam and Eve. Even so, there is compelling evidence to suggest that the Ark really did reach Ethiopia17 (although not at the time of King Solomon) and that James Bruce was well aware of this fact and even entered Ethiopia in 1768 with the express intent of bringing it back to Britain.18

So was this the answer – a quest for the lost Ark of God? Had Bruce been the Indiana Jones of his day?

Perhaps.

Yet beyond his interests in the Kebra Nagast and the Ark of the Covenant, Bruce could hardly have been unaware of the rumours circulating Europe regarding the existence in Ethiopia of the forbidden Book of Enoch. Indeed, during the early 1600s a Capuchin monk visiting Ethiopia had secured a religious text written in Ge'ez which was at first believed to be a long-lost copy of this very book. The find caused much excitement in European academic circles. Yet when it was finally studied by an Ethiopian scholar in 1683, the manuscript was identified, not as the missing Book of Enoch, but as a previously unknown text entitled the Book of the Mysteries of Heaven and Earth.19

No one really knew what the Book of Enoch might contain. Until the 1600s, its contents were almost entirely unknown. Yet its title alone was so powerful that at least one person attempted to learn its secrets from the angels themselves. This was the Elizabethan astrologer, magus and scientist, Dr John Dee, who, working with an alleged psychic, Edward Kelley, used crystal balls and other scrying paraphernalia to invoke the presence of angels. The spirits told Kelley they would provide him with the contents of the Book of Enoch, and there is evidence to suggest that Dee did actually possess a 'Book of Enoch' dictated through Kelley's mediumship.20 It is not, however, thought to have in any way resembled the actual work of this name. In addition to this, Dee and Kelley developed a whole written language, complete with its own 'Enochian' script or cipher, from their trafficking with angels. This complex system of magical invocation survives to this day and is still used by many occultists to call upon the assistance of a whole hierarchy of angelic beings.21

Scaliger's Discovery

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, a major breakthrough occurred in the search for the lost Book of Enoch. A Flemish scholar named J. J. Scaliger, having decided to study obscure Latin literature in the dimly lit vaults of European libraries, sat down one day to read an unpublished work entitled Chronographia, written in the years AD 808–10 by a learned monk named George Syncellus. Having ploughed through lengthy pages of quite mundane sayings and quotes on various matters appertaining to the early Christian Church, he then came upon something quite different – what appeared to be extensive tracts from the Book of Enoch. Handwritten in Greek, these chapters showed that Syncellus had obviously possessed a copy of the forbidden work and had quoted lavishly from its pages in an attempt to demonstrate the terrible transgressions of the fallen angels. Scaliger, realizing the immense rarity of these tracts, faithfully reproduced them in full, giving the world its first glimpse at the previously unknown contents of the Book of Enoch.22

The sections quoted by Syncellus and transcribed by Scaliger revealed the story of the Watchers, the Sons of God, who were here referred to by their Greek title Grigori. It told how they had taken wives from among mortal women, who had then given birth to Nephilim and gigantes, or 'giants'. It also named the leaders of the rebel Watchers and told how the fallen angels had revealed forbidden secrets to mankind, and how they had finally been imprisoned until the Day of Judgement by the archangels of heaven.23

We may imagine the conflicting emotions experienced by Scaliger – on the one hand excitement, and on the other horror and revulsion. As a God-fearing Christian of the seventeenth century, when people were being burnt as witches with only the most petty charges brought against them, what was he to make of such claims? What, moreover, was he to do with them? Angels lying with mortal women and the conception of giant babies? What could this all mean? Was it true, or was it simply an allegorical story concerning the consequences of trafficking with supernatural beings such as angels? Merely by making copies of this forbidden text, he ran the risk of being accused of practising diabolism.

Yet this incredible chance discovery begged the question of what the rest of the book might contain. Would it be as shocking as these first few chapters appeared to suggest?

Bruce must have been aware of the controversial nature of the sections of the book preserved for posterity by Syncellus in the ninth century. He must also have been aware of the enormous implications of retrieving a complete manuscript of the Book of Enoch. It was perhaps for this very reason that he spent so long talking to the abbots and monks at the Ethiopian monasteries. In the light of this supposition it becomes crystal clear that one of the primary objectives of Bruce's travels must have been to secure and bring back to Europe a copy of the Book of Enoch.

And Bruce's efforts did not go unrewarded, for he managed to track down and obtain not one but three complete copies of the Book of Enoch, with which he returned to Europe in 1773.24 One was consigned to the National Library of Paris, one he donated to the Bodleian Library in Oxford; and the third he placed 'amongst the books of Scripture, which I brought home, standing immediately before the Book of Job, which is its proper place in the Abyssinian Canon'.25

The earth-shaking consequences of these gracious acts of literary dedication can scarcely have been realized by Bruce himself during his lifetime, for they would ultimately lead to the recirculation of heretical stories concerning humanity's forbidden trafficking with the fallen race. And yet from the very moment of Bruce's return to Europe with his precious Ethiopian manuscripts, strange events were afoot. Having deposited the copy with the Paris library, Bruce made tracks to return to England, where he planned to visit the Bodleian Library at his earliest convenience. Even before he had a chance to leave France, however, he learnt that an eminent scholar in Egyptian Coptic studies, Karl Gottfried Woide, was already on his way from London to Paris, carrying letters from the Secretary of State to Lord Stormont, the English Ambassador, desiring that the latter help him gain access to the Paris manuscript of the Book of Enoch, so that a translation could be secured immediately. Permission was duly granted to Woide, who after admission into the National Library wasted no time in making the necessary translation of the text. Yet as Bruce was to later admit in his magnum opus on his travels to Ethiopia 'it has nowhere appeared'.26

What therefore were the motives behind this extraordinary urgency in translating the Book of Enoch, before even the Bodleian Library had received its own copy? The absurdity of the situation lies in the fact that no outright translation of the valuable Ge'ez text was to appear in any language whatsoever for another forty-eight years.

Why this delay? Why should such an important piece of lost religious literature have been ignored for so long, especially since there were now not one but two extant copies available to the theological world? This ridiculous situation must have infuriated James Bruce after he had gone to all the trouble of finding and securing these manuscripts in the belief that they would be presented to the public domain in a translated form before the expiry of his own life (he died in 1794).

Tempting as it may be to evoke the idea of some kind of organized conspiracy behind these extraordinary actions on the part of Woide and the English Secretary of State, the truth of the matter was far more mundane and lay in the economical and political climate of the time. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw a massive decline in the popularity of the Christian Church in many parts of Protestant Europe. Attendance at church services was dwindling, and churches everywhere were being neglected and left to fall into ruin under the impact of Newtonian science and the arrival of the Industrial Revolution. In an age of reason and learning, there was little place for the alleged transgressions of angels, fallen or otherwise. Most of the general public were simply not interested in whether or not angels had fallen through grace or lust, while any theological debate as to whether or not fallen angels possessed corporeal bodies was simply not a priority in most people's minds.

The Book of Enoch remained in darkness until 1821, when the long years of dedicated work by a professor of Hebrew at the University of Oxford were finally rewarded with the publication of the first ever English translation of the Book of Enoch. The Reverend Richard Laurence, Archbishop of Cashel, had laboured for many hundreds of hours over the faded manuscript in the hands of the Bodleian Library, carefully substituting English words and expressions for the original Ge'ez, while comparingthe results with known extracts, such as the few brief chapters preserved in Greek by Syncellus during the ninth century.27

It is fair to say that the publication of the Book of Enoch caused a major sensation among the academic and literary circles of Europe. However, its disturbing contents were not simply being read by scholars, but also by the general public. Churchmen, artists, writers, poets all sampled its delights and were able to form their own opinions on the nature of its revelations. The consequences of this knowledge passing into the public domain for the first time were to be enormous in many areas of society.

Romantic writers, for instance, became transfixed by the stories of the Sons of God coming unto the Daughters of Men, and began to feature these devilish characters in their poetic works.28, 29 A little later, Victorian painters started portraying this same subject matter on canvas.30 One might even be tempted to suggest that the Book of Enoch was a major inspiration behind the darker excesses of the so-called Gothic revival, which culminated in such literary works as Bram Stoker's Dracula, in which the eponymously named character is himself a fallen angel.31

Why should such satanic subjects have inspired or repulsed people to this extent? Why are people so fuelled by stories of fallen angels?

It also seems certain that the Book of Enoch was readily accepted as a work of great merit among the Freemasons, who used it to revive their ancient affiliation with the antediluvian patriarch; indeed, my own 1838 copy of Laurence's translation once belonged to the library of the Supreme Council 33°, the highest ranking enclave of Royal Arch Freemasons in Britain. There is even a rumour that the third copy brought back to Europe was presented by Bruce to the Scottish Grand Lodge in Edinburgh.32

Gradually, as the Oxford University edition of the Book of Enoch reached wider and wider audiences, scholars began checking in library collections across Europe, the result being that many more fragments and copies of the Enochian text in Ethiopian, Greek and even Latin were found tucked away in neglected corners. New translations were made in German and English, the most authoritative being that achieved in 1912 by Canon R. H. Charles.33 Even a sequel to the original text entitled the Book of the Secrets of Enoch was found in Russia and translated in 1894.34

Since that time, the authenticity of the Book of Enoch has been amply verified with the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Many fragments of copies written in Aramaic have been identified among the hundreds of thousands of brittle scraps retrieved over the years from the caves on the Dead Sea, where they were placed in around AD 100 by the last survivors of the Essene communities at Qumrân and nearby En-Gedi.35 The Ethiopian copyists had kept true to the original Aramaic text, which had probably passed into their country in its Greek translation sometime during the second half of the fourth century AD.36 For generation after generation, the Book of Enoch had been copied and recopied by Ethiopian scribes, the old battered and torn manuscripts being either cast away or destroyed during the many bloody conflicts that took place in Abyssinia over a period of fifteen hundred years.

The fact was that somehow the Book of Enoch had survived intact, despite its heavy suppression by the Christian Church, and it was to the authoritative English translation made by Canon R. H. Charles in 1912 that I would next turn to discover for myself the dark secrets within its pages. Only by absorbing the obscure contents of this unholy treatise could I begin to understand why its forbidden text had become abhorrent to so many over the previous centuries.