ANGELS IN EXILE

Exactly where did the legends of the Watchers originate? Had they been carried into the Essene communities of the Dead Sea by wandering zaddiks, the wild rainmakers who claimed direct descent from Noah and preached the teachings of the Kabbalah? If so, then who were these people and where had they obtained such stories? Had they been passed on by word of mouth among the Israelite tribes since time immemorial? Or did they have some more recent point of origin, perhaps in another Middle Eastern country?

Maybe the key lay in the Bible itself; which, despite the late construction of some of its individual books, could often be dated like the rings of a tree. To the trained eye the approximate date at which certain religious themes, passages or ideas first entered mainstream Jewish thought could be calculated with some degree of accuracy. Therefore, if the term 'îr, 'watcher', appeared in the Bible itself, then I had every chance of predicting when and how the term first filtered into rabbinical teachings.

Reaching once again for Hitchcock's New and Complete Analysis of the Holy Bible, I turned to Cruden's Concordance and thumbed through until I found the entries for 'watcher'. There turned out to be just four. The first, in the Book of Jeremiah, speaks of 'watchers' who 'come from a far country, and give out their voice against the cities of Judah', foreigners being implied here, and not angels.1 The other three references, however, all appeared in the Book of Daniel, one of the very last works of the Old Testament.

Before checking out these entries in Daniel, I again played with Cruden's Concordance, this time with respect to named angels, like those frequently mentioned in the Book of Enoch. I quickly discovered that just two are recorded in the whole of the Old Testament – Gabriel and Michael – and both appear only in the Book of Daniel. Even more significant was the knowledge that only in the Book of Daniel do there appear clear descriptions of Watcher-like beings that closely resemble those found in both the Book of Enoch and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Why should this be so? What was so special about Daniel?

By the Rivers of Babylon

The Book of Daniel is written partly in Hebrew and partly in Aramaic. Scholars usually date its contents and style to somewhere around 165 BC, the very time-frame attributed to the construction of the Book of Enoch, with which it is so often compared.2

From a historical point of view, the book focuses on an era beginning in around 606 or 605 BC, when the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar invades Judah and enters Jerusalem. There he sacks the Temple of Solomon and carries away many of its treasures, and on his return to Babylon takes with him some of the city's leading craftsmen. He also takes into his service three or four noble youths, one of whom is Daniel, who is thought to have been around seventeen years of age at the time. According to the bible story, the youths are taken into the care of the royal court and possibly even live in the king's palace. Daniel quickly rises in popularity to become a remarkable figure of great renown, noted for his strict adherence to the Torah, the Holy Law established by Moses, and for his 'wisdom'. He also possesses other more highly prized qualities, including the ability to interpret dreams. In time Daniel becomes governor of the province of Babylon as well as chief governor over the city's 'wise men' – its astrologers, Chaldeans (learned men) and soothsayers.

During this period Nebuchadnezzar apparently experiences a very strange dream. None of the 'wise men' can interpret its meaning, so the king summons Daniel. In his presence, Nebuchadnezzar then recites the contents of his vision in which he has seen 'a tree in the midst of the earth', with 'fair' leaves and fruit, that grew and grew until it reached heaven. Beneath its boughs were the beasts of the field sheltering in shadow, while the fowl of the air 'dwelt in its branches'.3 Nebuchadnezzar then apparently saw 'a watcher and an holy one [who] came down from heaven'. This shining being cried out to the king, telling him to cut down the tree and leave only 'the stump of his roots in the earth'.4

These verses in the Book of Daniel are then followed with the lines:

The sentence is by the decree of the watchers, and the demand by the word of the holy ones; to the intent that the living may know that the Most High ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will, and setteth up over it the lowest of men.5

Daniel, having listened to Nebuchadnezzar's recital of his dream, explains that the mighty tree represents the king himself, whose 'greatness is grown, and reacheth to heaven, and thy dominion to the end of the earth'. It foretells, he says, his imminent downfall, unless, that is, he breaks free of his bonds and accepts the Most High as the only true God.6 Then finally, for the third and last time, the term 'îr, 'watcher', appears in the text: 'And whereas the king saw a watcher and an holy one coming down from heaven.'7

Nowhere else in the Bible does the term 'îr appear in connection with the appearance of angels. This placed its usage firmly in the time-frame of the Book of Daniel, written at around the same period as the Book of Enoch. Even further supporting this link is the way in which Nebuchadnezzar's downfall is prophesied by tree-felling imagery, exactly as the destruction of the Watchers is described in some of the Enochian material found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.8

The Jews in Exile

The prophet lived long, and was still present at Nebuchadnezzar's palace when events took a turn for the worse for the Jews back in his native Jerusalem. The city had been left alone by the Babylonian army for some years when a new uprising forced Nebuchadnezzar to return to Judah and again besiege the capital. It fell in the year 598 BC, and on his return to Babylon the king is said to have taken into captivity an estimated 10,000 Jews. Another uprising in 586 BC apparently forced him to return once more to Jerusalem, and this time he not only sacked the Temple, he also razed it to the ground. He is also said to have returned to Babylon with almost the entire population of Jerusalem. This must have amounted to a figure upward of 100,000. Henceforth the people of Judah join those already in bondage and enter what is referred to in Jewish history as the period of captivity, or exile.

Nebuchadnezzar eventually dies in 562 BC and is followed by a succession of rulers, the last of whom, Belshazzar, also features in the prophet's story. Daniel apparently continues as governor and dream-interpreter, eventually rising to the position of 'third ruler' of Babylon, after the 'second ruler' Belshazzar, and the 'first ruler' Nabonidus (or Nabû-na'id) – Belshazzar's father, who has left the affairs of the kingdom in the hands of his son while he himself is off fighting a war in Arabia.

It is in the first year of Belshazzar's reign that Daniel is himself troubled by an apocalyptic 'night vision' in which he sees many strange things that act as portents of future events. In this the prophet witnesses a Watcher-like being, with an appearance that could have been lifted straight from the pages of the Book of Enoch, for he says:

I beheld till thrones were placed, and one that was ancient of days did sit: his raiment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like pure wool'.9

Comparisons with the description of the infant Noah as given in the Book of Enoch are obvious.10 Had one account influenced the other? Which came first – the Book of Daniel or the Book of Enoch?

The now elderly prophet is also called upon by Belshazzar to interpret strange handwriting that appears on a wall during a great banquet. The prophet predicts imminent doom, and soon afterwards Belshazzar is killed as Babylon falls to the Persians under the command of Cyrus the Great; the date being 539 BC. One of Cyrus' kinsmen, Darius, is set up on the throne of Babylon, and it is after this date that Daniel is cast into the lions' den because of his fidelity to God. According to the story, the prophet is saved from certain death by divine intervention, and afterwards Darius is said to have issued a decree enjoining 'reverence for the God of Daniel'.11

Daniel himself continues to experience dream-visions. For instance, during the third year of Cyrus' reign, presumably over Babylon, the prophet is said to have fasted for three weeks and while standing on the banks of the great river Hiddekel – the ancient Akkadian name for the Tigris – beheld:

a man clothed in linen, whose loins were girded with pure gold of Uphaz: his body also was like the beryl, and his face as the appearance of lightning, and his eyes as lamps of fire, and his arms and his feet like in colour burnished brass, and the voice of his words like the voice of a multitude.12

The similarity between the divine being in this account and the 'very tall' men with 'faces' that 'shone like the sun' and eyes 'like burning lamps', who appear before Enoch as he rests in his bed, is undeniable.13 Only the colour of their skin has changed – from 'as white as snow' in the Enochian text to 'burnished brass' in the Book of Daniel.

The Watcher-like being before Daniel can be seen only by him; however, as the prophet stands trembling at the awesome sight, the apparition announces that he has been negotiating with the Persians, yet, in the words of the angel:

the prince of the kingdom of Persia withstood me one and twenty days; but, lo, Michael, one of the chief princes, came to help me: and I remained there with the kings of Persia.14

The identity of the radiant being is never made clear, though its purpose in the waking vision is to inform Daniel of the fate about to befall the exiled Jews now that the Persians have taken Babylon. Yet here, too, is the first reference in the Old Testament to the archangel Michael, who is said to have come to the aid of the apparition during his negotiations with the Persians, a seemingly human action surely outside the domain of angels. Exactly what is going on here is unclear, though it is worth noting that in Hebrew tradition Michael is the archangel who presides over the heavenly affairs of the Israelite nation.15

After taking Babylon, Cyrus the Great continues westwards until, just one year later, in 538 BC, he takes Jerusalem. It is only then that the Jews of Babylon are finally given their freedom. An estimated 50,000 apparently return, leaving six times this amount in the land to which they had been taken in bond.16 Many thousands more journey two hundred miles eastwards to the city of Susa, the old Elamite capital in south-west Persia, where Darius had established a summer palace. Why there should have been this reluctance among the Jews to return to their native country is open to speculation. Perhaps they did not wish to make the long journey back to Jerusalem on foot, or had elderly relatives who would never have survived the return. It is also possible that many of the Babylonian Jews saw new opportunities opening for them, not just in the land that had become their only home, but in Persia itself. Furthermore, both Cyrus and Darius had extended a religious tolerance to those Jews who remained in Babylon and Persia, enabling them to practise their faith relatively unhindered.

According to the Book of Daniel, the now elderly prophet is among those who move on to the Persian court at Susa. Earlier, however, during the third year of Belshazzar's reign, Daniel experienced another dream in which he was taken in mind to the city of Susa. Here he witnessed a symbolic struggle between a ram and a he-goat (representing the overthrow of the Persian Empire by the Greeks, which does not occur until 330 BC). He also heard 'a man's voice between the banks of Ulai (a river named the Choasper, or Kerkhan, laying some twenty miles north of Susa), which called, and said, Gabriel, make this man to understand the vision.'17

Following these lines, Gabriel then makes his one and only cameo appearance in the Old Testament to explain to Daniel the meaning of his dream-vision. The archangel does not appear again until he announces the birth of both John the Baptist and the virgin-born child to Mary in the New Testament's Gospel of Luke.18

Daniel finally dies in Susa, a very old man indeed; however, the plight of the Jews in exile is not yet over. Large numbers stay on in Babylon and Susa until the new Persian king, Artaxerxes, signs a decree permitting the restoration of the Jewish state in 458 BC; the Temple of Jerusalem having been completed and rededicated in 515 BC. Yet still there is a reluctance among the Jews to return to their homeland. Some 5,000 return in the company of a priestly scribe named Ezra, following Artaxerxes' signing of the decree, while in 445 BC a further batch travel with a Jew named Nehemiah, who, prior to the journey, had been cup-bearer, or vizier, to the king.19 After thirteen years overseeing the restoration of the revitalized Jewish nation, Nehemiah returns to his royal master in Persia, where he finally ends his days. Any Jews still remaining in either Babylon or Susa after this date are simply lost to the pages of history.

A Man of Many Faces

The works accredited to Daniel contain potent, moralistic stories that won favour among the Jews following their return from exile. This was especially so during the terrible suppression they suffered under Antiochus Epiphanes, the king of Syria, who ruled Judaea at the commencement of the Maccabean revolt of 167 BC. It is almost certainly because of these troubled times that many of the fireside stories remaining from the days of the Babylonian Captivity were put into written form.

In all likelihood Daniel was a composite figure, a man of many faces, who embodied the life and deeds of more than one individual, perhaps even certain aspects of the various kings whom he allegedly served. To the post-exilic Jews, however, Daniel represented the imprisoned spirit of God's chosen people, from the time of the Captivity right down to the commencement of the Christian era. In the light of this, could I now make sense of why it was only in the Book of Daniel that Watchers, Watcher-like individuals and named angels appeared as heavenly beings in the Old Testament?

Chart I. RELEVANT BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY.

c. 2000 BC

Abraham leaves the city of Ur; Chedorlaomer, the King of Elam, encounters giant races in Canaan.

c. 1300–1200 BC

Exodus out of Egypt by the Israelites under the command of Moses the Lawgiver. Establishment of Twelve Tribes in Canaan; giant races again encountered here.

c. 1020–970 BC

The future king David fights the Philistines, including the giant Goliath of the tribe of Gath.

970 BC

Following the death of David, Solomon takes the throne of a united Israel.

931–889 BC

Solomon dies and the kingdom gradually splits into two separate kingdoms – Israel in the north and Judah to the south.

722 BC

The northern kingdom of Israel falls to the Assyrians and some 28,000 Israelites are taken into captivity; this signals the end of Israel as a nation. The captives never return from Assyria.

606–605 BC

Nebuchadnezzar succeeds to the Babylonian throne.

598 BC

Jerusalem, the capital of Judah, falls to Nebuchadnezzar. The outgoing king, Jehoiakim, and many leading craftsmen are deported to Babylon; these include the young Daniel. Jehoiakim's son Zedekiah takes the throne.

586 BC

Nebuchadnezzar besieges Jerusalem once more. The city falls and is destroyed; the Jews are taken into captivity in Babylon.

Nebuchadnezzar dies and is succeeded by three successive kings: Amelmarduk, Neriglissar and, finally, Nabonidus. Afterwards the regent, Belshazzar, takes control of Babylon in the king's absence.

540–539 BC

Nabonidus is defeated by Cyrus, king of Persia. Anarchy breaks out in Babylon; the Bible speaks of writing on the wall appearing in Belshazzar's palace during a banquet. Cyrus' army enters Babylon and achieves easy victory.

538 BC

Cyrus takes Jerusalem; all captive Jews in Babylon are allowed their freedom; many move on to Susa in south-west Persia.

537–515 BC

Restoration of the Temple of Jerusalem under Zerubbabel.

478 BC

The Jews still in Susa; biblical story of Esther marrying Xerxes, the Persian king, and thus saving many Jews from massacre.

458 BC

Ezra is sent to Jerusalem by the Persian king Artaxerxes. He takes with him a large number of the remaining Jewish exiles, as well as valuable gifts for the restored Temple.

445 BC

Nehemiah, the Jewish cup-bearer to Artaxerxes at Susa, returns to Jerusalem as its new governor. Kingdom of Judaea is founded.

165 BC

The Book of Daniel is written.

On the Road with Raphael

For the moment I would need to set aside the Book of Daniel, and the Bible as a whole, for I felt this could tell me little more about the origins of the Watchers. Instead, I turned my attention to the so-called Apocrypha, the collection of seventeen books, or portions of books, that, although originally included in the Christian Bible, were dropped by the early Church Fathers of the fourth century AD. I was looking specifically for one book, the Book of Tobit, for it had emerged that this featured another of the so-called archangels – in this case Raphael, who never appears in the Old Testament, but does appear as one of the holy Watchers in the Book of Enoch.

The Book of Tobit focuses on the lives of Israelites belonging to the ten tribes who were apparently carried off to Assyria and 'the cities of the Medes' after the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel to Shalmaneser, the Assyrian king, in 722 BC. Yet, unlike the Jews of the Babylonian Captivity, these tribes never returned from their exile, and are assumed to have lived on in isolated communities for many generations afterwards. Like the Book of Daniel and the Book of Enoch, this apocryphal work was actually constructed only sometime after 200 BC.

The story in question features a righteous man named Tobias, the son of Tobit, who is about to leave Nineveh, the old Assyrian capital, for Ecbatana, one of 'the cities of the Medes', in north-west Iran.20 Here Tobias is to win the hand in marriage of a fair maiden named Sara, the daughter of Raguel.21 His companion on the long and wearisome journey is Raphael, whose name means 'healer of God'. As they cross the mountains towards their place of destination, the archangel – who withholds his true identity and instead uses the name Azarius – teaches Tobias many wise things. For example, Tobias catches a huge fish in a river, and Raphael instructs him on how he can use each part of its body by saying:

Take out the entrails of this fish and lay up his heart, and his gall, and his liver for thee; for these are necessary for useful medicines . . . the gall is good for anointing the eyes, in which there is a white speck, and they shall be cured.22

Worthy words for a healer of God, but an art surely beyond the normal undertakings of a divine messenger of heaven. The journey resumes, and on reaching Ecbatana the archangel is sent on to Rages, another Median city, to collect bags of money on behalf of Tobias' family.23 Tobias himself eventually wins the hand of Sara, and on the party's return to Nineveh, Azarius reveals his true identity as 'Raphael, one of the seven holy angels',24 a reference to the group of seven archangels in Hebrew myth and legend.

There seemed little doubt that the story of Tobias and Raphael's journey on the road to Media was merely a quaint fable, created for an allegorical purpose by Jewish story-tellers. Yet the appearance of the archangel in this story seemed important, for it was beginning to look as though angelic beings with specific descriptions, identities, hierarchies and titles had only been adopted by the Jews after their return from exile in Babylon and Susa. If this were true, then from where exactly had these new influences come?

Babylon under the kings Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar in the sixth century BC had been dominated by the cult of Bel, or Bel-Marduk, the state god who was seen as a personification of the sun. His worship was abhorred by the Jews as pagan idolatry, even though Daniel, on entering the Babylonian court, had been given the name Belteshazzar, meaning 'prince of Bel'.25 Since Bel was the god of their oppressors, his cult would never have found favour among the captive Jews, so is unlikely to have had any major influence on the Jewish concept of angels. On the other hand, Babylon at this time was a cosmopolitan city attracting religious cults from every corner of Mesopotamia, so might one of these have found favour and sympathy among the Jews? It is difficult to say, though there is good reason to believe that the Assyrian and Babylonian winged temple guardians and sky genii influenced the development of the multi-winged Cherubim and Seraphim. Yet these were never really classed as mal'akh, the angels or messengers of heaven.

Iranian Influence

A more fruitful line of inquiry was the major influence that the Persian priesthoods undoubtedly exerted upon the exiled Jews. Many Jewish scribes, prophets and administrators achieved popularity and wealth not just in the old Elamite capital of Susa, but also much deeper into Persia, especially in the north-western kingdom of Media, modern-day Azerbaijan, the setting for much of the Book of Tobit. So what religious influences might the Jews have been exposed to here?

Before becoming a kingdom in its own right, Media had been a confederation of fierce, mostly highland tribes who had been vassals of the Assyrian Empire of northern Iraq and Syria, before proclaiming their independence in 820 BC. Thereafter they had been ruled by a dynasty of kings, who were known as 'king of kings', the last of whom was overthrown by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Two years later, with the unification of all the Iranian and Asian kingdoms, Cyrus established the Persian Empire, initiating a royal dynasty of kings referred to by historians as the Achaemenids. Cyrus now ruled a territory that stretched as far north as the Russian Caucasus, as far east as India and the Chinese Turkman Empire; as far south as Egypt and Ethiopia, and as far west as eastern Europe.26

It is not recorded to what faith Cyrus belonged, though it is likely he followed the religion of the Magi, the Median priestly caste of immense power, who were said to have guarded Cyrus' white marble tomb at his capital city of Pasargadae in southern Persia following his interment in 530 BC.27 Cyrus himself was descended of the old Median dynasty, so he also owed its powerful Magian priesthood some kind of loyalty.28 The origin of this priest1y line is unknown. The Medians were a mixed race, with indigenous cultural and religious influences from the mountainous regions of north-west Iran. The only real comparison to the Magi was the Brahman priestly caste of India, with whom they shared many aspects of belief, customs and worship (see Chapter 8). The most famous Magi were, of course, the three 'wise men' who, so the Bible informs us, brought the three gifts for the infant Christ at the time of the Nativity.29

Had the Jews therefore been influenced by the beliefs of the Magi? It was strongly possible; however, there was another, rival religion beginning to take a hold in Persia at this time and this was Zoroastrianism.

The Magi received their biggest blow in 522 BC when a Median usurper and Magus named Gaumata posed as the regent of Cambyses II, Cyrus' successor, while the king was on a military campaign in north Africa. In so doing the impostor managed to seize control of the Persian throne and proclaim himself ruler of the empire. Cambyses, on hearing of the coup, set about returning to Persia, only to be mortally wounded on the home journey. In spite of this tragic accident, Gaumata and his Magi co-conspirators were eventually ousted and slain by Cambyses' successor, Darius, having controlled the empire for several months.30 Thereafter the Magian priesthood was outlawed and persecuted throughout Persia. Indeed, according to the Greek writer Herodotus, on the anniversary of Gaumata's downfall a festival known as Magophobia was instituted. On this day people were encouraged to kill any Magi priests they came across, a custom apparently still taking place in the mid fifth century when Herodotus himself visited Media.31

The relegation of the Magian priesthood to one that was scorned and hated by the people allowed the sudden rise in popularity of what later became known as Zoroastrianism, a revitalized form of Iranian religion named after its much celebrated founder, Zoroaster. From the reign of Darius onwards, Zoroastrianism grew to become the new state religion with its own holy books, priesthood and temples in every major town and city. It did everything it could to stamp out Magianism, even though Zoroastrianism probably owed almost its entire creed to the Median religion's ancient teachings.

The Tower of Daniel

The Median capital of Ecbatana, the modern city of Hamadan, was held to be a very sacred place by both the Magi and the Zoroastrians. It was therefore quite astounding to find that it had been not only the place of destination of the archangel Raphael in the Book of Tobit, but also the site of a 'tower' – constructed by the prophet Daniel and sanctioned by his patron, Darius 1. According to the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (AD 37–97), the only writer to have preserved any knowledge of this elegant building's great renown, it was said to have been:

Chart 2. RELEVANT PERSIAN CHRONOLOGY.

2000–1000 BC

Establishment of Iranian tribes in central and western Asia, following migrations from the plains of southern Russia.

c. 2000–550 BC

Assyria, Media, Babylonia and Lydia are the dominant powers in the Near East.

630 BC

Traditional birth-date of Zoroaster, the founder of the Zoroastrian faith.

581 BC

The birth of Cyrus the Great, a direct descendant of the Median dynasty of kings.

559–548 BC

Cyrus assumes throne of Anshan in western Persia and then conquers the rest of the Iranian continent; establishment of the so-called Achaemenid period of Persian history.

539 BC

Babylonia falls to Cyrus.

530–522 BC

Death of Cyrus and reign of his successor Cambyses II.

526–521 BC

Dynastic troubles; a Magian usurper seizes the Persian throne for four months. Cambyses dies on return from Egypt. His successor, Darius I, assumes control.

485 BC

Coronation of Xerxes, son of Darius.

464–330 BC

Reigns of Artaxerxes I to Darius III.

330 BC

Defeat of Persia by Alexander the Great; end of independency and influence; cessation of Achaemenid dynasty of kings.

Establishment of Parthian dynasty in Persia.

224–5 AD

Ardashir I defeats Parthians in three decisive battles and establishes second Persian Empire, also known as the Sassanian dynasty of kings.

640 AD

Fall of the Sassanian kings after their final defeat by the invading Arabs; end of Persian Empire.

. . . wonderfully made, and it is still remaining, and preserved to this day; and to such as do see it, it appears to have been lately built, and to have been no older than that day when anyone looks upon it . . . Now they bury the kings of Media, of Persia, and Parthia, in this tower, to this day; and he who was intrusted with the care of it, was a Jewish priest; which thing is also observed to this day.32

If this was correct, then it clearly demonstrated the immense esteem accorded to the Jewish priesthood by the Persian kings, and presumably by the Magi, right down to the first century of the Christian era when Josephus wrote these enigmatic lines. Nothing more was known about Daniel's tower, though classical writers say that Ecbatana was originally surrounded by seven walls, each rising in gradual descent and painted a different colour, reminiscent of the seven-tiered ziggurats of Assyria and Babylonia.33

Quite obviously there must have been a trafficking of ideas and philosophies between the Magi of Media, the Zoroastrians of Persia and the Jewish exiles. Yet, if this were so, just how much of it might have influenced the contents of the Book of Enoch and the writing of the Dead Sea Scrolls? More important still – had Iran been the point of origin of the post-exilic concept of angels, both of the heavenly and fallen varieties? From even a cursory glance at the teachings of Zoroastrianism, it seemed the answer was always going to be yes.

The Angels of Zoroaster

Like Judaism, Zoroastrianism is a monotheistic religion. And like Judaism, it also accepts a whole pantheon of angels, or yazatas, who act in accordance with the faith's supreme being, Ahura Mazda, the 'wise lord'. Those angels closest to godhead are known as the Amesha Spentas, or Amshashpands, whose origins are thought to have developed out of much older Indo–Iranian myths of central Asia dating back to the second or third millenium BC.34 These six 'holy, immortal ones', or 'bounteous immortals', with Ahura Mazda, are equated directly with the Judaic concept of the seven archangels,35 who are found, not just in the Book of Tobit, but also in the Book of Enoch36 and the Dead Sea literature.37

Two notable scholars of Hebrew, W. O. E. Oesterley and T H. Robinson, recognized the influence of Zoroastrianism on Judaism in connection with everything from its concept of angelology to its understanding of demonology, dualism, eschatology, world-epochs and the resurrection of the soul, especially in the case of the Book of Enoch. Furthermore, they concluded that these adoptions from the Persian religion undoubtedly occurred when the Jews were in exile at Susa.38 These very same opinions have been shared by scholars of Persian antiquity, such as Richard N. Frye, a former Aga Khan Professor of Iranian Studies at Harvard University, who outlined the powerful cross-fertilization between Zoroastrianism and post-exilic Judaism in his 1963 book The Heritage of Persia.39

There seemed little doubt that I was on the right track in my conclusion concerning the Persian influence on the Book of Enoch, so what about the story of the Watchers – had this come from Iran as well? Canon R. H. Charles, the Hebrew scholar whose English translation of the Ethiopic Book of Enoch still stands among the finest to be produced, appeared to think so. He concluded that the myths concerning the Sons of God coming unto the Daughters of Men, as presented in Genesis 6, belonged 'to a very early myth, possibly of Persian origin, to the effect that demons had corrupted the earth before the coming of Zoroaster and had allied themselves with women'.40

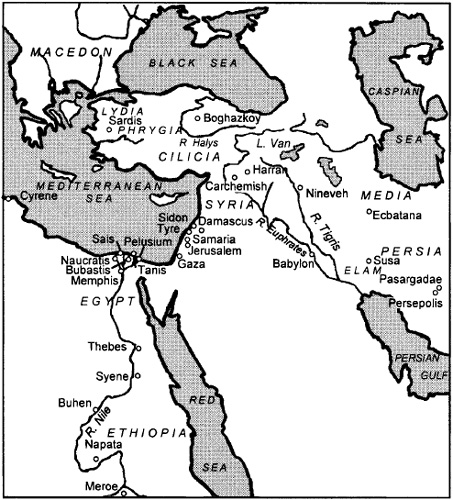

Map 2. The Near East in the first millennium BC.

This same opinion was voiced by Professor Philip Alexander, probably one of the foremost authorities on the Book of Enoch. In an important paper entitled 'The Targumim and Early Exegesis of "Sons of God" in Genesis 6', published in the Journal of Jewish Studies in 1972, he had this to say about the origin of the Sons of God:

Angelology flourished in Judaism after the Exile under the influence of Iranian religion. It is very likely that the interpretation of the Sons of God,  , as angels was one of the ways in which these rather alien ideas were grafted into the stock of pre-exilic religion and

naturalized.41

, as angels was one of the ways in which these rather alien ideas were grafted into the stock of pre-exilic religion and

naturalized.41

In other words, there seemed every possibility that the legends concerning the Sons of God had first been introduced to Genesis, or certainly revised and restored, at the time when the priestly scribes were busy re-editing the Old Testament, following the Jews' final return from Persia around 445 BC. Since the 'Sons of God' was simply another name for the Watchers, it implied that the traditions concerning their fall, as presented in the Book of Enoch, had stemmed originally from Iran.

Truth and the Lie

Persia would also appear to have had a major influence on the Dead Sea literature. For example, in the Testament of Amram it features the two Watchers who appear to Amram, the father of Moses, as he rests in bed. They ask him 'which one of us do you choose to rule you?', following which they identify themselves as 'Belial . . . [Prince of Darkness] and King of Evil' and 'Michael . . . Prince of Light and King of Righteousness'42 Elsewhere in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Belial, the Evil One, is equated with adjectives such as 'Darkness' and 'Lying', and 'the Liar', while his equal and opposite number, Michael, or Melchizedek, is tied with terms such as 'Light', 'Righteousness' and 'Truth'.43

The concept of the beholder of the vision being made to choose between light and darkness, truth and lie, righteousness and falsehood, is matched exactly in the Zoroastrian holy books, where an individual is asked to choose between asha, 'righteousness' or 'truth', and druj, 'falsehood' or 'the Lie'. These dualistic principles are represented on the one hand by Ahura Mazda, the 'wise lord', and on the other by Angra Mainyu (often abbreviated to 'Ahriman' in Persian texts), the 'wicked spirit' or 'prince of evil', who is the Iranian equivalent of Belial, Satan or the Devil.44 The idea of a choice is also strangely reminiscent of the way in which a Jew must choose between either the path of good or the path of evil during the annual festival of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

Further confirmation of this link between Zoroastrianism and Dead Sea literature comes from the fact that the followers of the truth among the Essenes were known as 'the Sons of Zadok', i.e. 'Righteousness', or 'the Sons of Truth', while the followers of Belial were known as 'the Sons of Darkness' and 'the Sons of Lying'.45 Now we may compare this with Zoroastrian literature, where it speaks of the ashavans, the 'followers of Righteousness' or the 'followers of Truth', and the drvants – the 'followers of the Lie'.46

These were important realizations, for they overwhelmingly confirmed the clear relationship not just between Zoroastrianism and Judaism, but also between the Iranian faith and the teachings of the Dead Sea communities, which, like Daniel, adhered strictly to the laws of Moses. Since there seemed every likelihood that these same religious communities were also responsible for such apocryphal and pseudepigraphal works as the Book of Enoch and the Testament of Amram, there seemed every possibility that the source material for the legends concerning the fall of the Watchers really had come from the rich mythology of Iran.

Yet before I followed in the footsteps of Daniel and departed Palestine for the land in the east that lay beyond the mountains of Babylonia, I still needed to establish one final fact: had anyone ever actually suggested that the Book of Enoch was composed outside of Palestine?

Laurence's Lucky Hunch

Canon R. H. Charles appeared to confirm the Persian influence on the Book of Enoch, but what about Richard Laurence, Archbishop of Cashel, who translated the first English edition of the Ethiopic text deposited in the Bodleian Library by James Bruce of Kinnaird in 1773? What had he to say about the text's country of origin? I read his lengthy introduction to the Book of Enoch and was astonished by what I found. Once he had decided to consider the latitude in which the text is set, he then made a detailed study of the length of the days referred to in Chapter 71. He found that the author of the Book of Enoch had divided these into eighteen parts, or segments, with the longest day consisting of twelve parts; the equivalent of sixteen hours in our own twenty-four-hour clock. Laurence realized that a longest day of this length does not occur in Palestine, this fact instantly dismissing it as the original setting for the Book of Enoch. In this knowledge, he searched for a northerly latitude that experienced a longest day of the time span indicated in the text. In so doing, he was able to conclude that the author was referring to an indigenous climate:

not lower than forty-five degrees north latitude, where the longest day is fifteen hours and a half, nor higher perhaps than forty-nine degrees, where the longest day is precisely sixteen hours. This will bring the country where he wrote, as high up at least as the northern districts of the Caspian and Euxine (or Black) Seas; probably it was situated somewhere between the upper parts of both these seas.

If the latter conjecture be well founded, the author of the Book of Enoch was perhaps one of the tribes which Shalmaneser carried away, and 'placed in Halah and in Habor by the river Goshan, and in the cities of the Medes'; and who never returned from captivity.47

Laurence knew he was in the right area. To his mind, the Book of Enoch could not have been written in Palestine, but had been composed much further north in the region of Russian Armenia, Georgia or the Caucasus, some 5° north of Iran. Although I had doubts concerning the precise region implied here, I had surmised similar conclusions myself after studying the descriptions of the Watcher-like entities referred to in the Enochian texts. These in no way resembled the olive-skinned Jews of Palestine, but instead conjured the image of tall, fair-skinned individuals with white hair and dark feather coats, surviving in a much cooler climate, like that experienced in more mountainous terrains.

Despite these almost wild assertions he had made, the archbishop could not help but continue to believe that the Book of Enoch must have been written by a Jew, but one obviously living in the region under question. As a consequence, he put forward the theory that the text's author had perhaps belonged to one of the ten tribes supposedly deported to Assyria and Media following the fall of Israel in 722 BC.

Such a hypothesis made little sense, although the proposed link between the author of the Book of Enoch and the ancient kingdom of Media did strike some sort of a chord. In the archbishop's day, scholars had no clear understanding of Zoroastrianism, nor could they have conceived of its heavy influence on Jewish religious thought, this fact making Laurence's detailed observations all the more pertinent to my own study. Clearly, then, here was yet further proof that I should look towards Iran, and in particular to the Magi priesthood of Media and the Zoroastrian faith of Persia, for the next set of keys to unlocking the mysteries of the fallen race.