THE PEACOCK ANGEL

October 1846. Upper Iraq. Austen Layard, the British explorer, diplomat, titan of archaeology and lover of oriental customs ascended the foothills, north of Mosul, on a sturdy horse. For the trip into Iraqi Kurdistan he was accompanied by Hodja Toma, the dragoman of the vice-consulate, and a priest, or kawal, sent to act as their mountain escort by Sheikh Nasr, the chief priest of the Yezidis, a Kurdish religious sect known to Europeans as the 'devil-worshippers'.1

After a night spent in a small hamlet near Khorsabad, the party continued across open plains to the village of Baadri, the home of the sect's chief, Sheikh Hussein Bey. As the village came into view, the Yezidi leader appeared in person on the horizon. Following behind him on foot was an entourage of priests and villagers adorned in flowing robes and wearing thick headgear in either black, brown or white. As they approached, Layard realized that Hussein Bey was 'one of the handsomest men' he had ever seen. At around eighteen years of age, he had regular and delicate features, lustrous eyes, and long dark ringlets that fell from beneath his thick black turban.

Layard endeavoured to dismount so as to greet the Bey courteously, but before he had a chance to do so, the fellow attempted to kiss his hand, a ritual he promptly refused to oblige. Instead the two men embraced, while still on their horses, as was the manner of this country. The Bey insisted that the two of them should dismount and walk together. This done, they strolled side-by-side, exchanging pleasantries as they entered the village.

Inside the chief's salamlik, or reception room, filled with carpets and cushions, a stream of fresh water passed by them, fed from a neighbouring spring. All running water was of immense sanctity to the Yezidi, as it was to both the Magians and the Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Once the Englishman and the 'devil-worshipper' had begun engaging in conversation, an audience of curious villagers started to gather at the other end of the room. They simply listened in respectful silence, seemingly with the Bey's full permission.

How different were the two cultures represented by these two great men. Sir Austen Henry Layard (1817–94) had been responsible for the recent excavations on behalf of his patrons Sir Stratford Canning and the British Museum at the ancient ruins of Nimrud, the Assyrian ruins situated at the confluence of the Tigris and Upper Zab rivers, near the city of Mosul.

As a traveller, Layard respected the native religions of the region, and this included the secretive Yezidis of the Kurdish foothills. He had heartily accepted an invitation from the Bey to be the first European to witness the sect's strange rites during its yearly Jam, or religious festival. This was to take place over a several-day period in the village of Lalish. Being a good Christian, Layard naturally had reservations about attending such a devil-worshipping festival, but these fears were fast being alleviated in the company of the religion's tribal leader.

The isolated Yezidi tribes were probably the most obscure of the three quite separate yet interrelated cults of the yazata, yazd or yezad, the Persian for 'angel' or 'angels', which still thrived in certain parts of Kurdistan. Each paid lip-service to the Islamic faith, whether of the Shi'ite or Sunni persuasion, and yet each also held true to its own unique cosmogony, mythology and ritual practices, which had more in common with Magian or gnostic dualism than with the Muslim or Judaeo-Christian faiths.

The Angelicans

The appellation of 'devil-worshippers' had been given to the Yezidis by the earliest European travellers, yet their creed ventured far beyond such an ignorant description. The name Yezidi derived from the nature of their beliefs, which focused primarily around an indigenous breed of angelic beings. In many ways their name can be translated as the 'angelicans', and originally this would appear to have been the name by which all the Kurdish angel cults were known. Yet chief among the Yezidi angels was a unique and very important figure indeed. His name was, and still is (for the Yezidis still exist), Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel. He corresponds with the Judaeo-Christian concept of the Evil One – Satan or Lucifer – but this association hardly does him justice, for Melek Taus is seen as a supreme being, with authority over worldly affairs. To these people he was the creator of the material world, which he made from the scattered pieces of an original cosmic egg, or pearl, inside which his spirit had previously resided.

According to one Yezidi text known as the Mes 'haf i Resh, or 'the Black Book' – the contents of which were entirely unknown to Europeans in Layard's time – it reveals that:

In the beginning God (Kurdish Khuda) created the White Pearl out of his most precious Essence; and He created a bird named Anfar. And He placed the pearl upon its back, and dwelt thereon forty thousand years. On the first day [of Creation], Sunday, He created an angel called 'Azâzil, which is Melek Tâwus, the chief of all [angels].2

The beliefs of the Yezidi tribes of Kurdistan are littered with ornithomorphic themes. The Anfar is almost certainly a cosmic form of the Persian and Zoroastrian Simurgh bird. More importantly, the Yezidi holy book, which is thought to date in its present form to the thirteenth century AD, states that the first name of the Peacock Angel had been 'Azâzil, an Arabic rendering of Azazel, one of the leaders of the Watchers in Judaeo-Christian apocrypha.

Yezidis have attempted to contain their own limited, and often contradictory, knowledge and understanding of the Peacock Angel within the Islamic account of the fall of Azazel, or Eblis. According to the Koran, the Fallen Angel was outcast by God for having refused to bow down before Adam, the creature made of clay, since he himself had been born of fire. In the traditional rendition of the story, Azazel is doomed to walk the earth eternally, but according to the Yezidi version, God forgave Azazel, who was then reinstated in Heaven.

The Peacock Angel is undoubtedly seen by the Yezidi tribes as a form of Satan, or Shaitân as he is known in Arabic, since every effort is made not to mention this name out aloud. Fail to do so and the culprit would be struck blind. This fanatical attitude goes so far as banning the use of words that even sound like Shaitân. Furthermore, no one is allowed to make a curse in the name of Shaitân, unless it is out of earshot of neighbours and is directed at those not of the faith.3

Like the Zoroastrians and the Dead Sea communities of postexilic Judaea, the angelicans of Kurdistan have always revered whole pantheons of yazatas, or angels. And in similar with these other angel worshippers, the Yezidi hold that a group of seven, sometimes six, head the angelic hierarchy – these, of course, can be equated with both the Iranian concept of the Amesha Spentas and the Judaeo-Christian belief in seven archangels. The leader of the main Yezidi group of angels is Lasifarûs, a cosmic incarnation of Melek Taus, who is specifically said to speak Kurdish, as if to demonstrate his indigenous nature.4 Scholars have attempted to connect his name with Lucifer, the Christian form of Satan, which seems highly probable indeed. The rest of the seven angels are given standard Christian-Islamic names such as Jebra'il (Gabriel), Mika'if (Michael), Ezra'il (Azrael) and Esrafil (Raphael). Another angelic hierarchy of the Yezidi are the Chehelmir, or Chelmir, who number forty.

All this was, of course, quite unknown to Layard as he sat with the current Yezidi leader Hussein Bey in his salamlik. He was the son of one of the greatest sheikhs of their tribes, Ali Bey, who had defended their people against countless attacks from Kurdish Muslims, the Ottoman Turks, as well as the Islamic armies of both Iraq and Iran. Quite obviously they saw the Yezidis as not just infidel, but as heretics par excellence, fit only to be wiped out completely unless they renounced their faith and became Muslims themselves.

In past centuries the Yezidis had been very powerful, covering extensive areas all over Kurdistan, but slowly their tribes had been persecuted and destroyed until there were now only isolated groups left in the Iraqi and Turkish foothills of Kurdistan, as well as further south in the vicinity of Jebel Sinjar, a solitary mountain in the Iraqi desert, whose name translates as the mountain of the 'bird'.5 Yezidis have also survived in small pockets across central Kurdistan, as well as in the Russian Caucasus and in various satellite communities in northern Syria, Lebanon, Anatolia and Iran. Today their tribes represent some 5 per cent of the Kurdish population,6 yet as each year passes their numbers diminish even further.

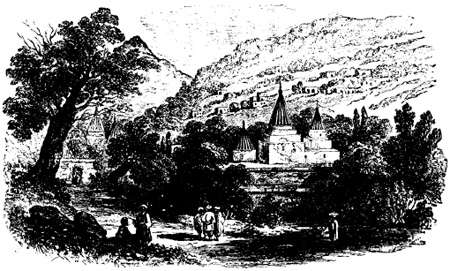

Fig. 6. Entering the village of Lalish in the foothills of Iraqi Kurdistan. Here Yezidis come each year for the annual Jam festival in honour of their principal avatar, or saint, Sheikh Adi. The conical towers, or mazârs, mark Yezidi shrines and tombs.

Layard spent the evening pleasantly chatting with Hussein Bey, and in the morning the two men travelled by horse to Lalish. Hussein himself was dressed in bright robes, and accompanying them was a large contingent of horsemen, who constantly discharged guns into the air and sang Yezidi war songs. Also with them were musicians, who played pipes and tambourines, and a whole procession of Yezidi villagers, who followed behind on foot. The journey was long and arduous, seemingly ever upwards. Occasionally the party would be forced to dismount from their horses and ascend precarious mountain paths in single file.

Having reached the summit of one final pass, the party looked down into a wooded valley to see a large cluster of buildings, interspersed here and there with brilliant white conical spires, each one vertically ribbed into many ridged sections. Known as mazârs, these towers marked the position of Yezidi shrines and tombs. All at once the tribesmen discharged their guns into the air in celebration of their arrival at Lalish. Almost immediately this indiscriminate use of firearms was answered by another volley of shots from the village itself.

As the procession descended down into thick oak woodland, it began to pass many other pilgrims making their way to the tomb of Sheikh Adi, the cult's main avatar (the living incarnation of a divine being), in whose honour the annual Jam festival is held. He is supposed to have lived during the twelfth or thirteenth century AD, and is believed to have been an incarnation of Melek Taus himsel( Even though Sheikh Adi is recognized as the founder of the Yezidi faith, both the religion and the tribes are ascribed a much earlier date of origin. Interestingly enough, the Yezidi sacred work entitled the Mes'haf i Resh is written in a very ancient Kurdish language known as Kermânji, which, at the time of its composition in the medieval period, was confined to the rugged Hakkâri mountains south of Lake Van, close to the suggested location of the Garden of Eden. Indeed, this very area was the traditional stronghold of Sheikh Adi, who, despite a belief among modern Yezidis that he was born in the Bekaa Valley of Lebanon, was once known as Adi al-Hakkâri, or Adi of Hakkâri.7

Roots of the Yezidi

Sheikh Adi had obviously revitalized an existing set of beliefs already adhered to among the Kurdish tribesmen, yet where exactly these people had obtained their quite unique religious views is not known. Yezidi cosmogony and mythology were unquestionably non-Christian and non-Islamic in origin, although they did appear to bear some striking similarities to the teachings of the Persians, in particular the religion of the Magi. The Yezidis believe in a form of dualism, where they give equal respect to both the 'good' and 'evil' principles of their religion. This therefore paralleled the Magi's belief in the eternal struggle between the ahuras and daevas, the root of virtually all later dualism in the Near East. So were the Yezidis descendants of the Median Magi? The answer has to be yes, for the angelicans believe that the next incarnation of Melek Taus will come in the form of a personage named Sheikh Mêdî, or Mahdî – an avatar who will bear the blood and power of the ancient spiritual leaders of Media.8 That the Yezidi are among the last survivors of the faith of the Magi is not disputed. Scholars are in no doubt that it was the Magi, and not the Zoroastrians, who had influenced the development of Yezidism.9

Clinching the connection was the belief among the Yezidi that Sheikh Adi had himself been a Magian. According to the Wigrams in The Cradle of Mankind: 'there seems some historical evidence that he (Sheikh Adi) lived in the tenth century (a disputed date), and that he was originally a Magian who had fled from Aleppo (in Syria) when the Magian cult was suppressed'.10 It was he who had established the Yezidi creed and sacred books, and it will be his spirit that is going to come again in the final days; hence the prophecy about the incarnation of Melek Taus as Sheikh Mêdî, or Mahdî.

The Shrine of Sheikh Adi

As Hussein Bey and Layard journeyed through the oak wood, they watched as women broke away from their chores to rest for a few minutes and as the men busily reloaded their rifles in readiness for the next party of pilgrims to appear over the mountain pass. Soon the European and the sheikh were greeted by the chief Yezidi priest Sheikh Nasr. He approached with the principal members of the priesthood, who were all dressed in white. Nasr appeared to be about forty years of age, and the warmth with which he and his priests greeted Layard was commendable. They all insisted on kissing his hand as he remained on his horse, despite his clear dislike of this custom. Hussein and Layard then dismounted and began the last part of the journey on foot.

The tomb of Sheikh Adi contained an outer and inner courtyard which led into a darkened room within which was the saint's tomb. This ancient building had almost certainly once been a Nestorian church, before these local Christians had departed the area.11Layard quickly realized that entry into the inner courtyard was by barefoot only, so he removed his shoes before venturing-further. Once inside the open enclosure, he sat down alongside Hussein Bey and Sheikh Nasr on the carpets provided. Only the sheikhs and kawals, the two principal orders of priesthood, were allowed to join them in this sacred area. Each took seats around the walls of the precinct, some of which was shaded by enormous trees that grew within the courtyard. Beyond them on all sides was a rocky valley that seemed to act as a natural amphitheatre overlooking the events taking place below, for pilgrims were already gathering beneath the shades of trees or on roof-tops in readiness for the evening's proceedings. At one end of the sanctuary was running water said to issue from a spring that had been miraculously diverted to this place from the more famous spring of Zemzem at Mecca by Sheikh Adi himself.

The Black Serpent

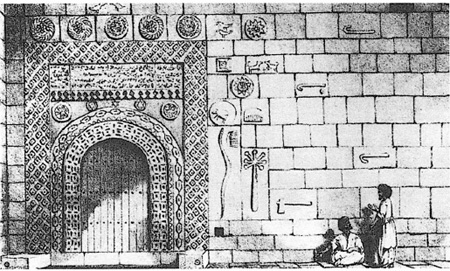

Around the east and west doorways into the darkened tomb was an assortment of devotional images carved in high relief. Many of these were obscure, their symbolism uncertain. They included items such as combs, assorted birds (probably peacocks), crescents, hatchets, stars, as well as various animals, including a lion. Most striking of all was a long, black snake carved to the right of the eastern entrance, close to where tiny red flowers had been attached to the wall using black pitch.12 Layard tried in vain to find out the meaning of this serpentine form from Sheikh Nasr, who merely stated that it had been carved for decoration by a Christian mason some years beforehand. This explanation, Layard quickly realized, was a little short of the truth, for the carving was paid the highest respect by all Yezidis who daily coated it in charcoal to preserve its stark black lustre.13 Each person, on entering the tomb, would stop to kiss the black snake, as if it held some special place in their personal beliefs.14

And Layard was right, for the serpent did hold a special significance in the Yezidi religion. Not only was it venerated on feast days,15 but it was also a symbol of totemic magic. Descendants of certain Yezidi sheikhs, in particular Sheikhs Mand and Ruhsit,16 the latter being found in the villages of Baiban and Nasari in the Mosul Vilayet, believed they had power over serpents and were immune from the effects of snake poison. European travellers referred to these people as snake-charmers, for they would go from village to village displaying their magical talents to any household willing to pay them.17

Fig. 7. The exterior wall of Sheikh Adi's tomb within the Yezidi village of Lalish in Iraqi Kurdistan. To the right of the door is the much-venerated black snake, a symbol of Azazel, the Greatest Angel in Yezidi beliefs.

The British author E. S. Drower, whose book Peacock Angel is one of the only documented studies of the Yezidis, encountered a snake-charmer and his 'ugly little' daughter ]ahera, or 'Snake-Poison', during a visit to the village of Baashika in 1940. Mrs Drower described how she watched the sheikh, a descendant of Sheikh Mand, and his daughter enter a courtyard with huge patterned snakes coiled around their shoulders. The father then proceeded to remove the serpent from his daughter's neck before dropping it to the ground. It slithered 'along in the sparse grass looking very evil indeed. It was five or six feet in length and its body two inches or more in thickness.'18 The sheikh then caught the snake and placed it back on the child's shoulders. Mrs Drower having given the odd couple 'an offering', the sheikh and his daughter posed for photographs, holding the snakes' flat heads close to their lips, before moving on to the next household.19 Mrs Drower asked her Yezidi host whether the claims regarding the magical powers attributed to the snake-charmers were real, only to be told that they had seen Jahera handle a poisonous snake fresh from the fields, and that the snakes do not have their fangs removed.20

Snake-charming is a form of showmanship. It is also the outer manifestation of snake shamanism, which appears to have been extremely important to the angel-worshipping Yezidis since time immemorial. The fact that these magical talents were said to have been passed down from generation to generation implied a hereditary lineage of immense antiquity. It is unclear exactly what the serpent represented to the Yezidi, although its veneration would suggest that it played a similar role to that of the Peacock Angel, in other words it was a symbol of Azazel, or Shaitan. It must also have represented the spiritual energy and magical potency of the snake shamans themselves.

So where had this symbol of magical potency come from? Did it signify, not only the hereditary shamanism among the Yezidi, but also its original source? Snake shamanism and viper-like features would appear to have been characteristics associated with the Watchers. So if they really had existed as an actual culture living in this same region during prehistoric times, then it was possible that the Yezidis' veneration of the serpent was a memory of their presence and influence.

Power of the Evil Eye

Layard noticed that in the centre of the inner courtyard in front of Sheikh Adi's tomb stood a square plaster case, inside which was a small recess filled with what seemed to be small balls of clay. These were eagerly purchased by the pilgrims as if they had some special purpose to play. On inquiring as to what was going on, Layard was informed that these balls had been made from mud collected from the actual tomb of Sheikh Adi, which is placed next to a muddy spring. Yezidis regard them as sacred relics able to ward off evil spirits, including the evil eye, which is paid unparalleled attention among all the Kurdish faiths. For instance, at a Yezidi sacred place named Dair Asi in the Sinjar region, there is a secret rock cleft where 'those afflicted with the influence of the "evil eye" deposit their gifts in order to alleviate their misfortune'.21 Yet even more fearful of the evil eye are the Muslims and Christians, for as Mrs Drower recorded, few mothers 'would dare to take their babies abroad without sewing their clothes over with blue buttons, cowries, and scraps of Holy writ, either Qur'an or Bible'.22 Blue is the Yezidis' most sacred colour and is never worn by them for this reason, yet to all the other Kurdish faiths it is used to ward off the evil eye. Why was there this great fear of the evil eye in Kurdistan? And why did the colour blue play such a contradictory role among the Kurdish faiths? The matter of the evil eye is discussed in a subsequent chapter, but the colour blue I shall deal with now.

In the Persian Shahnameh turquoise blue is the colour of sovereignty and kingship. The Pishdadian kings wore blue crowns and garments, a tradition also echoed in ancient Sumer and Akkad, where the monarchs were adorned in items fashioned from blue lapis lazuli stone. Since the mythical kings of Iran were said to have borne strong physiological features of the daevas, then perhaps this colour was deemed to possess divine characteristics appertaining to the fallen race. If so, it might explain why later generations of humanity came to either revere or fear this colour, depending on the nature of their faith. Evil has always been used to ward off evil, which is why church gargoyles and grotesques are said to keep away demons, and why eye charms are used to repel the evil eye, so blue must have been used by Kurdish Muslims and Christians in a similar capacity.

The Jam Begins

At midday, Sheikh Nasr, the chief priest, stood up, signalling that everyone else should do likewise. Layard followed suit, walking with the party as it moved from the inner to the outer court, which by now was a hive of frenzied activity. Some peddlers sold handkerchiefs and cotton items from Europe while others sat before bowls of dried figs, raisins, dates or walnuts collected from different parts of Iraqi Kurdistan. Men and women, boys and girls, appeared to be involved in feverish conversation, the din rising at the sight of Hussein Bey and Sheikh Nasr, whom they now respectfully saluted. The party continued through the outer court and moved into the open air, where an avenue of tall trees offered a welcome shade. A constant sound of pipes and tambourines pervaded the air as Layard joined the various sheikhs and kawal priests, who proceeded to sit down in a circle around a sacred spring. All watched as women approached to take water from the little reservoir below the fountain.

As this was in progress, lines of pilgrims continued to approach along the avenue of trees. Layard could not help noticing among them 'a swarthy inhabitant of the Sinjar' with long black ringlets and piercing black eyes. Over his shoulder was slung a matchlock gun, while his long white robe rustled about in the warm breeze. Behind him came the rich and the poor – men in colourful turbans with ornate daggers in their belts, women wearing long, flowing gowns with their long hair in neat tresses, and poverty-stricken families dressed in ragged white clothes. They all approached the fountain, as if it was the penultimate station along the pilgrim route to the tomb of their saint. The men would lay down their arms before kissing the hands of Hussein Bey, Sheikh Nasr and the white-skinned European, who was treated with equal respect by everyone. They then made their way towards a small stream where each person washed both themselves and their dirty garments in readiness to enter the outer courtyard. As this was happening, firearms were still being discharged in response to those who announced their own entry into the valley in a likewise manner.

Perpetual music, song and dance filled the afternoon, and eventually Layard decided to retire to the roof of a nearby building. Here he was supplied with food by black-turbaned fakir priests and a wife of Sheikh Nasr. Down below in the inner court other fakir priests had appeared carrying lamps and cotton-wool wicks that were placed in niches on the outer walls of the tomb as well as in the surrounding valley. Layard saw that Yezidis would run their right hand through the flame and then rub the opposite eyebrow with the resulting black soot. Women would do likewise for young children, or for those less fortunate than themselves. As in the Magian and Zoroastrian faiths, fire is sacred to the Yezidi.

As nightfall came, the valley looked star-spangled with a myriad of tiny flames flickering in the cool evening breeze. But something else now stirred. Literally thousands of people – Layard estimated up to 5,000 – moved about the slopes like a great moving sea of orderly activity. Many carried lighted torches and lamps, further illuminating the trees dotted all around the valley.

Layard watched as large numbers of sheikhs, dressed immaculately in white; kawals, adorned in black and white; fakirs, wearing brown robes and black turbans; as well as numerous women priests attired in white, began to assemble in the inner court for what appeared to be the climax of the Jam festival. The kawals played sweet melodies on flutes and tambourines, which grew steadily in pitch and intensity. Accompanying the pleasant sounds was a slow choral chant that radiated from the men on the surrounding slopes. This continued unabated for over an hour, the pitch hardly varying at all. Occasionally contrasting harmonies would emanate from the priests positioned in the inner court. Gradually the whole bizarre cacophony quickened its pace and volume, until finally it blended to become an eerie wall of harmonic sound that seemed to hang motionless in the air.

The tambourines were then banged louder and louder as the flutes were played with ever more ferocity. Voices were raised to their highest pitch, while women warbled a strange low shrill that seemed to make even the rocks reverberate with constant sound. Overcome by the ecstasy of the highly charged atmosphere, the kawals began to discard their instruments as they started flinging themselves around in wild trances, induced by the almighty crescendo of noise. Each fell to the ground when their body could take no more.

And then the focus of their ritual was made apparent to the chosen few for the first and only time that day. In the inner court, out of view of the masses, a sheikh delicately clasped an item in a red cloth coverlet, something that appeared to be of immense spiritual significance to these people.

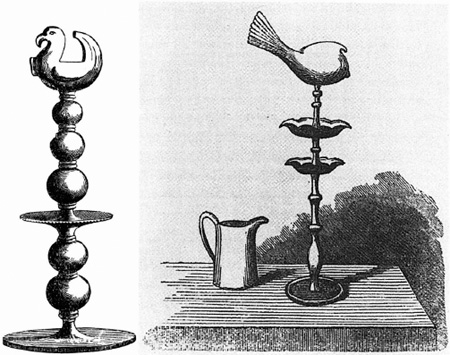

Slowly the priest removed the red covering, and immediately held aloft what lay beneath it. In his hand was a strange statue of a bird, made either of brass or copper. It was perched upon a tall stand, like a weighty candlestick, that appeared to be made of a similar metal. The image itself seemed crude with a bulbous body and a long hooked beak, like that of a predatory bird. Its name was Anzal, the Ancient One,23 the embodiment of Melek el Kout, the Greatest Angel, whose presence had now been summoned.24

This strange bird icon of immense antiquity was the Yezidis' chief subject of veneration. So who was the Greatest Angel? And what possible significance did this archaic worship have to my knowledge of the fallen race?

The Greatest Angel

Aside from the sculptured bird icon kept at the tomb of Sheikh Adi at Lalish, there were apparently six more of these so-called sanjaqs, a word meaning either 'standard' or 'dioceses'.25 Each of these examples was made to be carried in a dismantled state by travelling kawals, who would move from village to village looking for a suitable venue to conduct a very strange ceremony in which the priest would invoke the spirit of Melek Taus into the bird icon, using a form of trance communication.

The sanjaq icons are greatly revered by the Yezidis, and until 1892 it was claimed that none had ever fallen into the hands of enemies.26 Who exactly Anzal, the Ancient One, might have been is sadly not recorded. It was probably another form of Azazel, the Peacock Angel. A possible clue as to its identity may, however, come from the candlestick-like stand on which the images perch. This almost certainly symbolized the divine tree on which the Saena, or Simurgh bird, sat in Persian tradition, suggesting that these stands represented the seat of all knowledge and wisdom, passed on to Yezidis through the presence of the Ancient One.

That these metal images became identified with the peacock bird is a complete mystery since peacocks are not indigenous to Kurdistan. Some were introduced to Baghdad during the Middle Ages. They were also to be found in Persia, which is probably why Aristotle referred to them as 'the Persian bird'.27 Yet it is in the Indian state of Rajasthan that the peacock is most revered. Hindus here see it as sacred to Indra, the god – or asura – of thunder, rains and war. Much folklore and superstition also surrounds this bird in India. For instance, in similar with its mythical counterpart Garuda, it is said to be able to attack and kill snakes.28 It is also believed to hypnotize its intended female partner into submission,29 while its distinctive call and dance is said to announce the arrival of the monsoon rains.30

Figs. 8 and 9. Two examples of sanjaqs, the metal bird icons venerated by the angel-worshipping Yezidi of Kurdistan. On the left is one seen by Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1849, and on the right is another sketched by a Mrs Badger in 1850. Are these strange icons abstract memories of Kurdistan's protoneolithic vulture shamans?

Only the last accredited ability of the peacock is based on any truth, for the bird senses the oncoming rains and attempts to have one last fling before its feathers get so wet that it is forced to shed them! Yet the other two legends are significant in themselves, since they have both contributed to the bird's veneration among the Yezidi. Like the peacock, the Yezidi relish a power over serpents, as witnessed by the snake-charming descendants of Sheikhs Mand and Ruhsit. The hypnotic gaze of the peacock is integrally linked with the power of the evil eye, and it is interesting to note that peacock feathers have long been considered effective deterrents against this baleful influence.31

The striking blue, black and green eyes on a peacock's feather must also have played a major role in establishing the bird's sanctity among the Yezidi, especially since the colour blue is given such respect by their faith. Another curious superstition concerning the peacock feather is its believed ability to prevent the decay of any item placed with it, perhaps a distant echo of the connection between the Simurgh and the drug of immortality.32

Descendants of Noah

It was, however, the link between peacocks and rain-making that seemed of greatest importance, for as with the wild zaddik-priests of the Dead Sea, the Yezidis claim direct descent from Noah – in their case through an unknown son named Na'umi.33 They say that from Noah's other son, Shem, who was reviled by his father, came all the other races of the world. This therefore implied that the Yezidi tribes were not only unique, but that their ancestors had a special relationship with the hero of the Great Flood.

The Yezidis in fact believe there to have been two floods,34 not one – the last of which, the Flood of Noah, took place 'seven thousand years ago'.35 On what information they base this chronology is unknown. In their own rendition of the traditional story, the Ark had drifted on the open sea until it accidentally struck the tip of Mount Sinjar. A major disaster was averted, however, when the quick-thinking snake promptly slithered across to the gaping hole and corked the leak using its curled-up body. (The Armenian Church claims that this same incident occurred at Sipan Dağ, a mountain on the northern shores of Lake Van.)36 The vessel was then able to continue its journey, which ended, as in the case of Judaic, Islamic and Kurdish tradition, at Judi Dağ, not Mount Ararat.37 Yezidis attend the annual sacrifices that take place each year on Al Judi to commemorate the offerings given up to God by Noah after the Ark had come to rest on dry land.38

Nomadic Rainmakers

The Yezidis seem to possess a great affinity for the Noahic tradition, almost as if they believe themselves to be the inheritors of his succession, as well as the antediluvian cosmogony he brought with him into post-diluvian times. They see him, along with Seth and Enoch, as one of the 'first fathers' of their tribes, who they say were conceived by Adam alone.39 This intimate connection with Noah is highly significant, for as with the Dead Sea communities, the Yezidi recognize a certain type of wild, nomadic priest known as the kochek. These individuals are regarded as seers, visionaries, mediums and miracle workers – gifts which they apparently receive from hereditary sources. Moreover, like the zaddik-priests of the Dead Sea, the kochek have the power to bring rain. One folkstory recorded by the Yezidi scholar R. H. W. Empson tells how a kochek named Bêrû was asked by the sheikhs of various communities to bring rain during a particularly dry season. Having agreed to do this within seven days, the kochek ascended to heaven, where he managed to secure the assistance of Sheikh Adi himself Together they took the matter to a heavenly priest named Isaac (Is 'hâq), who informed Bêrû that his request would be granted. After seven days no rain had fallen, so the kochek was called before the Yezidi chiefs to explain himself He pointed out that heaven received so many requests for rain that they would have to wait their turn like everyone else. Shortly afterwards the rains did come, vindicating the supernatural powers of the kochek.40

Could it be that the kocheks' apparent ability to influence the weather was one of the feats originally accredited to the fallen race, for rain-making activities have always played a prominent role in shamanistic practices around the world. The fact that the Yezidi saw themselves as inheritors of ancient ancestral traditions going back to Noah would appear to hint at this possibility. If so, then there seemed little doubt that the geographical focus of this tradition has always been the area around Judi Dağ in Turkish Kurdistan.

The Secret Cavern

Yezidi myth and legend must contain many elements inherited from older indigenous cultures of the Kurdish highlands. Who these people were, and what their relationship might have been to the Watchers, is unknown, yet one tentative clue comes from a series of strange carvings greatly venerated by the Yezidi. They are situated in a cavern at a place named Ras al-'Ain, on the Syria-Turkish frontier, and were seen, and described to the Baghdad authorities, by E. S. Drower in 1940.

To reach this secluded site, Mrs Drower had followed an elderly Yezidi woman named Sitt Gulé up a precarious rock-face. The two had climbed higher and higher, using available crevices as footholds, until the woman took them around a right-hand bend where they suddenly encountered deeply worn steps. These entered a lofty cavern in which a gushing spring issued from behind a rock-face. On inquiring as to who was worshipped here, the woman had replied 'Kaf', or more correctly kahaf, a Kurdish word meaning 'cavern'. Yet Sitt Gulé clearly believed this to be the name of the genius loci, or guardian spirit, of the place, for she went on to point out his image to the Englishwoman.

Looking around, Mrs Drower noticed that the walls contained niches, blackened with the smoke of a thousand lamps, as well as various shelves for offerings and lights. There were also three large panels in which were carved extraordinary images of human forms. One was unfortunately defaced beyond all recognition. The second contained 'a single seated figure facing the worshipper, almost Buddha-like in its dignity and repose'.41 Although the figure was not cross-legged, he was seated in a 'concave frame', shaped like the lotus thrones of Buddhist art. He also wore 'a conical cap', like those worn by Tibetan holy figures. In the third panel was a 'seated and bearded personage also wearing a conical cap', and advancing towards him were a procession of people 'on a wave of movement and worship'.42

On the other side of the chamber, beyond the stream of running water and over the spring-head itself, was a human face in low relief Although somewhat damaged, it was similar in style to the other two figures, with a beard and conical hat. Yet it was what she saw cut into the polished floor that most baffled Mrs Drower, for she could trace 'an oblong with twelve small round depressions, placed six a side'.43 She surmised that this design represented some kind of 'gaming board', which seems unlikely bearing in mind the immense sanctity of the place.

To what ancient culture did this secret cavern once belong? And what did these strange carvings of holy figures, with beards and conical hats, seated on lotus thrones, actually represent? No one knows. The only thing that can be said with any certainty is that the carvings were extremely old, and did not belong to the faith of either the Yezidi or the Magi. The clear Buddhist appearance of these serene carvings cannot be overlooked, although they are unlikely to have had any direct connection with the teachings of Buddha, the Indian prophet, who is said to have died in 543 BC. The conical hats are variations of what became known in Greek classical art as the Phrygian cap, which usually denoted a person of Anatolian or Persian origin. The earliest wearer of the Phrygian cap, or cap of Hades, was the mythical hero Perseus, who was said to have brought 'initiation and magic' to Persia and to have founded the cult of the Magi to guard over the 'sacred immortal fire'.44 There is clearly a great mystery in these ancient carvings, and unravelling this could identify the origins behind both the Magi priesthoods of Media and the angel-worshipping cults of Kurdistan.

The great antiquity of the Yezidis is spelt out by themselves, for they employ enormously long periods of time to calculate the age of the world. They say there have been seventy-two different Adams, each living a total of 10,000 years, each one more perfect than the last.45 In between each Adam has been a period of 10,000 years, during which no one inhabited the world. The Yezidis believe that the current world race is the product of the last of the seventy-two Adams, making the earth a maximum of 1,440,000 years old. Such precise calculations are in themselves nonsensical; however, these figures (as I shall explain in Chapter Twenty-three) were not simply plucked out of thin air. Far from it, for they relate to astronomical time-cycles of extreme antiquity and represent a knowledge of universal numbers present in myths and legends world-wide.

I felt strongly that the ever-diminishing Yezidi cult held important clues in respect to the supposed presence of the fallen race in Kurdistan. Yet it was among another of the Kurdish angel cults, the mysterious and secretive Yaresan, as well as in the myths and legends of other local cultures, that their dark secrets are revealed in even greater detail.