WHERE HEAVEN AND EARTH MEET

The last years of the nineteenth century, Nippur, southern Iraq. Beyond the call of the distant muezzin the constant sound of pickaxes hitting the hard, stony ground filled the burning, dust-clogged air. Arab labourers, their heads wrapped in coloured headgear, worked furiously in the bright sunshine to clear away dirt and rubble from the rectangular trenches, cut deep into the ancient earth. Every hour some new find revitalized their enthusiasm to dig deeper.

News spread that fresh artefacts had been uncovered – close to the foundations of the E-kur, or Mountain House. This was the great temple of Enlil, the supreme god of the Sumerian pantheon and the legendary founder of this powerful city-state more than five thousand years earlier.1

On learning of this discovery, Professor J. H. Haynes of the Babylonian Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania, navigated the labyrinthine pathways between the trenches and ditches that seemed alive with frenzied activity. Finally he reached the remains of the E-kur temple, which stood beside the crumbling mud-brick ziggurat known to the Sumerians as Dur-an-ki, or the 'Bond of heaven and earth'.2

Guided by the voices of those who had made the find, Haynes quickly examined the newly dug pit. What he saw were eight fragments of a broken clay cylinder which, although partially defaced, clearly bore inscriptions in the wedge-like cuneiform alphabet. Its positioning, here among the ruins of the E-kur, strongly suggested that it was a foundation cylinder deposited following repairs on the temple during the reigns either of Narâm-Sin (2254–2218 BC) or his successor Shar-Kali-Sharri (2217–2193 BC), the last two kings of Agade, or Akkad, the royal dynasty of Semitic origin, who had ruled supreme in Sumer for a total of 141 years during the second half of the third millennium BC.3

Dr Haynes was never to know the immense significance of this foundation cylinder, or of the extraordinary inscriptions on some of the other clay tablets found during this period by his team in the vicinity of the E-kur building and dating to a similar age. Along with many other more highly prized treasures from Nippur and other Mesopotamian city-states, the broken cylinder and inscribed tablets were taken back to the University Museum of Philadelphia by the Babylonian Expedition's chief archaeologist, Professor H. V. Hilprecht. They were never removed from their packing cases, but instead were dumped in the museum's basement until their eventual rediscovery by George Aaron Barton, Professor of the Bryn Mawr College, Philadelphia, during the second decade of the twentieth century.4 Aware of Haynes's and Hilprecht's earlier work, Barton decided to translate the E-kur foundation cylinder, which he found scattered about in three different transit boxes.5

After many painstaking hours of dedicated work, Barton became more and more excited about the contents of the cylinder's inscription, which was written in unilingual Sumerian. Arranged in nineteen columns on the eight fragments were, he believed, 'the oldest known text' from Sumeria, and 'perhaps the oldest in the world'.6 It featured many of the ancient gods, including Enlil, Enki, the god of the watery abyss, as well as a little-known snake goddess named Sir. She seemed to be synonymous with Enlil's spouse, Ninlil or Ninkharsag, leading Barton to conclude that Nippur had once been a cult centre for this ancient snake goddess.7 By contrast, the contents of some of the other tablets he translated were seen by Barton as a trifle mundane; there was a version of the Sumerian creation myth and what seemed to be hymns and eulogies to deified kings or localized deities, but little else.

Despite his initial excitement in respect of the clay cylinder, Barton could only conclude that the Nippur tablets he translated exhibited 'the neighborly admixture of religion and magic so characteristic of Babylonian thought . . . If not the religious expression of a democracy.'8 So, having completed his work, Barton left behind the Nippur texts, which were published in 1918 by Yale University Press under the rather dull title of Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions, and there the matter rested for the next sixty years.

Then, during the 1970s, a copy of Barton's by now extremely rare book came into the possession of a former exploration geologist named Christian O'Brien. He had studied natural sciences at Christ's College, Cambridge, and had worked for many years in Iran with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now British Petroleum (BP). He was also a reader of cuneiform script and could see, even at a cursory glance, that Barton had misinterpreted much of what the E-kur foundation cylinder and some eight of the ten published Nippur tablets actually recorded, prompting him to retranslate each in turn. What he found shocked him completely.

As each new tablet was completed, more and more pieces of a slowly emerging jigsaw began to fit into place. Much of the texts appeared to tell the story of a race of divine beings known as the Anannage (a-nun-na(ge)), or the Anunnaki (a-nun-na-ki), the great, or princely offspring, or sons, of heaven and earth,9 who arrive in a mountainous region and set up camp in a fertile valley. They call the" settlement edin,10 the Akkadian for 'plateau' or 'steppe' (see Chapter Twelve), as well as 'gar-sag, or Kharsag, a term meaning, according to O'Brien, either the 'principal, fenced enclosure' or the 'lofty, fenced enclosure'.11

The Anannage gradually develop an agricultural community that includes land cultivation, field systems, plant domestication, and the creation of water-irrigation ditches and channels. Sheep and cattle are placed in covered pens, and cedar-wood houses are constructed as dwellings.12 Among the larger building projects undertaken by the Anannage is the construction of a reservoir to provide Kharsag with a more advanced form of land irrigation, as well as the erection of larger edifices, such as the Great House of the Lord Enlil, which stood on a rocky eminence above the Settlement.13 The texts also speak of a 'granary', the 'building [of] roads', 'a maternity building for mothers', and a place known as 'the Building of Life in the High Place'.14 In the valley surrounding the settlement are apparently 'loftily-built tree plantations', 'lofty cedar-tree enclosures' and orchards planted with trees that have a 'three-fold bearing of fruit'.15

The Kharsag tablets, as O'Brien began to refer to them, apparently detailed how the community had thrived for an immensely long period of time. Harvests were usually plentiful, with some excess grain being produced. It would even seem that they allowed outsiders into the community as both partners and helpers to 'share the bounty'.16

The principal founders of the settlement were fifty in number, the main leaders being Enlil, the Lord of Cultivation, and his wife Ninkharsag, the Lady of Kharsag, also known as Ninlil. Repeatedly she is referred to as 'the Shining Lady' and, more significantly, as 'the Serpent (Sir) Lady'17 – the title that had led Barton to assume she was some kind of snake goddess worshipped at Nippur. Also included in the group were Enki, Lord of the Land, and Utu, or Ugmash, a sun god. The Anannage possessed a democratic leadership, although a chosen council of seven would apparently come together when major decisions were made concerning the future of Kharsag.18 Just occasionally the supreme being, Anu, whose name means 'heaven', or 'highlands', would join the council to advise on their deliberations.

Different situations and events that arose in the settlement are outlined in some detail. For instance, one text speaks of a major epidemic that appears to have swept through Kharsag, for it explains:

The stone jars were pressed down with grain [i.e. there had been a good harvest]. The Serpent Lady hurried to the Great Sanctuary. At his home, her man – the Lord Enlil – was stricken with sickness. The bright dwelling, the home of the Lady Ninlil, was stricken with sickness.

Sickness . . . sickness – it spreads all over [the settlement] . . . Our splendid Mother – let her be protected – let her not succumb Give her life – let her be protected from the distress of sickness . . . There is no rest for this Serpent; from sickness to fever . . .19

Even Enlil and Ninlil's own son, Ninurta, is struck down by the mystery illness. His mother calls for all light to be shut out, both day and night until the child regains its health. Those affected do finally get better, although strict new laws are introduced in an attempt to ensure that there is no repeat of this mystery sickness, for as the text explains:

In Eden, thy cooked food must be better cooked. In Eden, thy cleaned food must be much cleaner. Father, eating meat is the great enemy – thy food at the House of Enlil.20

Having finished retranslating this particular tablet, O'Brien began to realize that he had hit on a prehistoric jackpot, for as he excitedly recorded at the time:

The parallels between this epic account and the Hebraic record at the Garden of Eden are highly convincing. Not only is 'Eden' twice mentioned [in this tablet alone], but the reference to the 'Serpent Lady', as an epithet for Ninkharsag . . . [is] clear confirmation of the scientific nature of the work carried out by the equivalent Serpents in the Hebraic account.21

The 'Serpents in the Hebraic account' was a reference to the Watchers and Nephilim of the Book of Enoch.

Even further confirming this link between Watchers and Anannage was the reference on two occasions to Ninlil's husband Enlil as the 'Splendid Serpent of the shining eyes'.22 This recalled the vivid descriptions of the Watchers given in the Enochian and Dead Sea literature, particularly in the case of the Testament of Amram.

Had O'Brien really uncovered an account of the Watchers of Eden?

The Fall of Kharsag

Later tablets spoke of a 'winter of bitter cold', unlike anything Kharsag had ever seen before. For a time the Anannage managed to hold out in the bleak arctic-like conditions, but more cataclysms were to follow. First there came a 'great storm'. Then there was further destruction from flooding, presumably after the snow and ice melted. A storm-water course was quickly constructed that stretched from the heights of the mountains to the edge of the plantations, and for a time this worked, keeping out the rising flood waters. Yet then an even harsher winter came upon them, and this would appear to have been the final straw, for as the tablet records:

The demon cold filled the land; the Storm darkened it; in the small households of the Lord Enlil, there were unhappy people. The House of Destiny was covered over; the House of the Lord Enlil disappeared [under snow] . . . The four walls protected the Lord from the raging cold. The fate of the Granary rested on its thick walls – it was preserved from disaster, from the power of the storm-water . . . The flood did not destroy the cattle.23

Warm clothes, communal gatherings and good cheer kept the remaining Anannage alive. Fires raged in enormous fireplaces, and it seemed they might survive the long winter, but then another disaster struck. The vineyard workers apparently made the decision to open the reservoir's sluice-gates in an attempt to 'irrigate morning and night'.24 Yet the 'firm, deep watercourse was destructive; its noise was great; the power of its flowing was frightening . . . in the night, many strong houses which the Lord had established, were flooded . . .'25

What happened next shall perhaps never be known, for the remainder of this particular tablet was too damaged for translation. The penultimate tablet speaks of even greater devastation, essentially by storms, but there is reference also to lightning destroying the shining house of Lord Enlil, and of the repeated presence of darkness ('darkness hung over the hostile mountains'26 and 'the goats and sheep bleated in the darkened land'27).

The final tablet speaks of mass disaster and lamentation. In the wake of the continual darkness, broken only by frequent thunderstorms, there came perpetual rain. The reservoir filled up and overflowed, quickly flooding the irrigated fields and then, finally, the low-lying parts of the settlement. Those buildings on higher ground were again said to have been struck by lightning, prompting Enlil and Ninlil, and presumably other Anannage, to try and contain the damage being inflicted on what remained of Kharsag.

Yet the end was at hand. The Anannage knew they were fighting a losing battle, forcing Enlil to admit:

'My Settlement is shattered; overflowing water has crushed it – by water alone – sadly, it has been destroyed.'28

The mass devastation caused during this period of climatic turmoil had brought to a close the idyllic settlement of Kharsag. O'Brien came to believe that this break-up of the Anannage had led to an important dispersal of individuals who inadvertently paved the way for the foundation of the city-states of Mesopotamia, some time around 5500 BC.29

From these god-men of a previous age had come the first Near Eastern civilization, controlled by a number of city-states. Each of these had been peopled by indigenous races, but administered by the direct descendants of the Anannage, the serpents with shining eyes. They had preserved the memory of the Kharsag settlement until its story was finally set down on clay tablets and deposited in the E-kur by Akkadian priests during the reign of either Narâm-Sin or Shar-Kali-Sharri.

Such was the mind-blowing story presented in The Genius of the Few, a book written by Christian O'Brien, with his wife Barbara Joy O'Brien, and published in 1985. Unfortunately, because O'Brien's book fell between the devil and the deep blue sea – in that it was shunned by both the academic community and the ancient mysteries audience – it did not receive the popular success it undoubtedly deserved. All copies quickly disappeared, but one luckily found its way into a second-hand bookshop in Maldon, Essex, where in 1992 my colleague Richard Ward noticed it among the shelves of books on archaeology.

Had O 'Brien Been Correct?

The explosive nature of Christian O'Brien's theory presented in The Genius of the Few was recognized immediately by Richard and myself. If O'Brien had been correct in his translation of the Kharsag tablets, then this was the most convincing evidence yet for not only the reality of Eden but also the independent existence of a highly advanced culture living in a mountainous region of the Near East during prehistoric times. O'Brien had identified the texts' 'serpents' with 'shining eyes' as the Watchers of the Book of Enoch, while in his opinion Kharsag was to be equated with the seven heavens visited by the patriarch Enoch.30

Even more significant was the reference to the council of seven Anannage who apparently came together to make major decisions on behalf of the Kharsag settlement. These so-called Seven Counsellors, or Seven Sages, were much celebrated in Sumerian myth and legend; furthermore, in Assyrian scripts belonging to the reign of King Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC), the seven Anannage, or Anunnaki, are mentioned in the same breath as the 'foreign gods' of Assaramazash, clearly a reference to the Iranian god Ahura Mazda and the six Amesha Spentas, thus inferring that the two sets of divine beings were perhaps one and the same.31 If this was indeed the case, then it meant that the council of seven Anannage were almost certainly the root source behind not only the Amesha Spentas but also the seven archangels of Judaeo-Christian tradition. These, it must be remembered, are cited in the Book of Enoch as the chief among the Watchers who remained loyal to heaven at the time of the fall.

There was, however, no indication among the Kharsag tablets of a 'fall' of the Anannage, although there is no reason to suppose that the texts were in any way complete. Moreover, references to the Anannage exist in other Sumerian texts, and these throw much greater light on the subject. It seems the Anannage were originally only gods of the 'heaven of Anu'. Only later had they been separated into two quite separate camps – the gods of heaven and the gods of ki, 'earth'. Amounts are even given – there were three hundred Anannage under the command of the god Anu in heaven and six hundred under the command of the underworld god Nergal, who lived 'in the earth'.32

Did this information constitute evidence, as O'Brien believed, of some kind of fragmentation of the original Kharsag settlement, whereby a large group of rebel Anannage had decided that instead of remaining in isolation among the mountains, they would descend on to the plains of ancient Iraq and live among humanity? Was this the same story as presented in the Book of Enoch concerning the 'fall' of the two hundred rebel Watchers? Certainly, there are various strange stories preserved in Sumerian mythology which relate how the Anannage had once walked among mortal kind. For instance, they were said to have designed and laid the foundations of the ancient Sumerian city of Kish.33 They were also 'put to work to help build the temple (in the city) of Girsu',34 while in another myth they were given a 'city as a place in which they might dwell'.35 This 'place' is likely to have been Eridu, Sumeria's oldest citystate, which is said to have had no less than fifty Anannage attached to it,36 the same number that appears in the Kharsag texts. Excavations have revealed that Eridu was founded as early as c. 5500 BC,37 the very date suggested by O'Brien for the break-up of Kharsag.

Yet had O'Brien been correct in his translation of the texts?

Academics who have followed in the footsteps of Professor George Barton would utterly dismiss O'Brien's rather 'colourful' interpretation of the Kharsag texts. They would support Barton's translation and reconfirm the orthodox view that they were simply miscellaneous religious texts of the late Akkadian period, c. 2200 BC. Furthermore, they would point out that the 'creation myths' contained on the tablets are conceptual and that any reference to Enlil and his Mountain House related to his temple at Nippur and not to some 'highland' settlement of the gods existing in prehistoric times. What O'Brien was therefore saying was utter nonsense and should be ranked alongside books on ancient astronauts and the lost land of Atlantis.

There the matter would rest.

One part of me wanted to believe this was correct. I struggle to support the more academic, down-to-earth views of our past history, as I know that straying too far off the beaten track can only mean ridicule and scorn, whether you are wrong or whether you are right. Yet O'Brien was no ancient astronaut theorist. His arguments against the orthodox interpretation of individual texts appeared convincing indeed.38 Admittedly, O'Brien appeared to be over-enthusiastically convinced that the Kharsag tablets represented something more than simply ancient Sumerian religious texts. Yet his translations made far more sense than those originally produced by Barton, and on this basis I would continue my own review of the subject.

In Search of Kharsag

All the indications were that Kharsag had been situated in a high mountainous region,39 so high in fact that 'some Anean trees could not be cultivated'.40 This does not appear to refer to the rugged plains around Nippur.

Where then had this highland settlement been located?

In an attempt to answer this question I studied various other early Mesopotamian texts and began to find tantalizing evidence for the existence of just such a mountain retreat of the gods. For example, the Akkadians of the third millennium BC would appear to have believed that Kharsag, or Kharsag Kurra ('gar-sag kurkurra) as it was also known, was a sacred mountain located to the north, 'immediately above'41 the northern limits of their country.42 To them it symbolized the cradle of their race, and was located in a kind of primordial version of Akkad itself.43 Here, too, were 'the four rivers',44 paralleling exactly the Hebraic concept of the four rivers of paradise. Beyond Kharsag Kurra 'extended the land of Aralli, which was very rich in gold, and was inhabited by the gods and blessed spirits'.45

Akkadian myth therefore blended together both the Hebraic account of paradise and the contents of the Kharsag tablets, lending immediate weight to O'Brien's retranslation of these ancient texts. So where had this mythical domain of the gods been located? There was no question on the matter. It lay immediately north of Akkad, in other words in the mountains of Kurdistan. The later Assyrians of the first millennium BC, who adopted many of the Akkadian myths and legends, had spoken of 'the heavenly courts' of Kharsag Kurra in connection with the 'silver mountain' – a reference to the Taurus mountain range of Turkish Kurdistan, west of Lake Van, which was known to the Akkadians as the Silver Mountain.46

A similar domain of the gods is featured in what must rank as Mesopotamia's most celebrated literary work – the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The Hero Gilgamesh

The Sumerian hero of this name had probably been a historical figure – seemingly a king of the city-state of Uruk in central Iraq, sometime during the first half of the third millennium BC. The texts say that he had been a lillu, 'a man with demonic qualities',47 and that he had been worshipped as a god at various shrines. At Uruk, for example, he is recorded as having been adopted as the personal deity of a king named Utu-heğal, c. 2120 BC, as well as by his immediate successors, who ruled from Ur, a city-state in Lower Iraq between c. 2112-2004 BC.

It was probably during this same age that a series of poems featuring the deeds of Gilgamesh were set down for the first time, for there exist several variations of his epic which date to the first half of the second millennium BC. Among these poems is one entitled 'Gilgamesh and Huwawa' or 'Gilgamesh and the Cedar Forest'.48 The story begins with the beguiling of Enkidu, a wildman who lives in the mountains, but who is finally tamed and persuaded to begin a new life among mortal kind.

Enkidu grows to enjoy his new lifestyle, but in so doing he loses his courage and strength, so Gilgamesh suggests that they go into the mountains where they must find and kill a 'monster' named Huwawa (or Humbaba). This strange being has been made guardian of a great cedar forest by the god Enlil. At first Enkidu is reluctant to embark on this fearsome quest, as he himself has come across Huwawa on his own journeys across the mountains; however, he finally agrees to the proposal on the insistence of Gilgamesh.

Huwawa is described as 'a giant protected by seven layers of terrifying radiance',49 who also possesses a hideous face, long hair, whiskers, and lion's claws for hands. Eventually the two heroes track down the giant, but at first spare his life. Then, in a fit of rage, Enkidu finally dispatches Huwawa.

The significant aspect of this poem is the section entitled 'The Forest Journey', where Gilgamesh and Enkidu approach the cedar forest for the first time. It is said to have stretched before them 'for ten thousand leagues in every direction', and as the text reveals:

Together they went down into the forest and they came to the green mountain. There they stood still, they were struck dumb; they stood still and gazed at the forest, at the mountain of cedars, the dwelling place of the gods [author's emphasis]. The hugeness of the cedar rose in front of the mountain, its shade was beautiful, full of comfort; mountain and glade were green with brushwood'.50

What was this 'dwelling place of the gods'? The text suggests it is the 'green' mountain that stood within the vast forest. In front of this mountain is a huge cedar that seems to have its own significance in the story. Such lone trees, usually of immense height and size, are found in mythologies throughout the world and represent the point where heaven and earth meet. In mythological studies, such trees are known as the axis mundi, or the cosmic axis, and almost invariably they are linked with certain recurring themes, such as a holy mountain and a spring or wellhead that supplies the whole world with water. Kharsag itself is described in the opening lines of one of the tablets as the place 'where Heaven and Earth met',51 confirming its role as a cosmic axis. It was undoubtedly also 'the dwelling place of the gods', for Enlil, Enki, Ninlil, Ninurta and Utu were five of the most important deities of the Sumerian pantheon.

So where exactly had this great cedar forest of the gods been located?

In the oldest forms of the Epic of Gilgamesh written in Sumerian, the text is quite clear: it is in the Zagros mountains of Kurdistan.52 Later forms of the epic written in Assyrian times speak of the forest as being in Lebanon, although this is almost certainly incorrect. Palaeo-climatological research has shown that such forests replaced the cold tundra and sparse grasslands that had covered the lower valley regions of the Kurdish highlands after the final retreat of the last Ice Age, somewhere around 8500 BC. The appearance of powerful Asian monsoons in northern Mesopotamia and north-western Iran around this time had brought about dramatic changes in the climatic conditions of the Kurdish highlands, creating vast inland lakes as well as the proliferation of lush vegetation during the spring and summer months. Thick forests of deciduous trees, including cedars, began to grow in the valleys and on the mountain slopes, while the higher elevations turned into lush grasslands, ideal for cultivation. Indeed, these severe climatic changes corresponded almost exactly with the first appearance of the earliest neolithic communities in Kurdistan (see Chapter Seventeen}.53 Yet then, sometime between 3000 and 2000 BC, these Asian monsoons slowly retreated, leaving the region devoid of its essential spring and summer rains. As a consequence, the lower valleys suffered most, with a reduction in the variety of vegetation, and a slow desiccation of the neighbouring lowland regions, a process that continues to this day.54

It was also during this last period of prehistory that the Sumerians began wholesale felling of these vast mountain forests, both for building construction and as charcoal for brick furnaces and domestic fires. As a consequence, by the start of the first millennium BC the cedar forests of the Zagros no longer existed. Not only did this bring about huge ecological damage to the region, it also paved the way for gross geographical inaccuracies both in later versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh, and in many other myths and legends of this period. Since the editors of these texts lived in an age when not even their distant ancestors could remember such a 'cedar forest' having ever existed in the Zagros, their presence in the texts was inadvertently associated with the more obviously well-known cedar forests of the Ante-Lebanon range. Indeed, as the Kurdish expert Mehrdad Izady points out: 'some modern scholars, noting the geographical discrepancy but perplexed by the long absence of any large cedar stands in the Zagros, have come to interpret the ancient words of the (Gilgamesh) epic as "Pine Forest" rather than "Cedar Forest" '.55

The Argument for Mount Hermon

Knowledge of the existence of these cedar forests in the Zagros mountain range of Kurdistan was a major blow to O'Brien's interpretation of the Kharsag tablets. Having assessed their contents, he had used almost identical palaeo-climatological evidence to establish that the cedar forests of the Lebanon dated back to the same post-glacial period, c. 8000 BC in his reckoning. With this knowledge, O'Brien concluded that the Kharsag settlement must have been located in the Ante-Lebanon range during this very same age. Indeed, he actually put forward a foundation date of 8197 BC for the settlement, based on these studies.56 O'Brien then went on to demonstrate that this information proved that Kharsag was synonymous with the Eden/heaven settlement of the Book of Enoch, because it had been geographically located in the vicinity of Mount Hermon, which is itself in the Ante-Lebanon range. Curiously enough, the Akkadian word for 'cedar' is erenu, or erin, which is phonetically the same as 'îrin, the Hebrew word for Watchers. As the term 'trees' is used as a synonym for the Watchers in Enochian literature, while the mythical kings of the Shahnameh are likened to cypress trees, I feel this etymological link between the Watchers and cedars must be more than simply coincidence.

Since there is clear evidence for the former presence of cedar forests in the Zagros, it seems much more likely that Kharsag was located either in this region, or in the eastern Taurus range, and not in far-off Lebanon. The most bizarre confirmation of this supposition comes from O'Brien himself, for after summing up the geographical evidence presented in the Kharsag tablets, he admits:

It is strongly reminiscent of the Zagros Mountains of Luristan and Kurdistan, to the north of Sumer, on the north-eastern flank of the Fertile Crescent. But these mountains are now oak-tree bearing, and have no history of cedar forests . . . We are left with only the far north-western part of the Fertile Crescent covered by Lebanon.57

This is simply not true, and even further damaging O'Brien's belief that Eden/heaven/Kharsag had been located in the Ante-Lebanon range was the reference in Genesis 2:8 to God planting a garden 'eastward, in Eden'. Mount Hermon cannot be seen as eastward of anything, other than the old city of Sidon on the Mediterranean coast. Despite these errors of judgement on O'Brien's part, the importance of his retranslation of the Kharsag tablets cannot be overstated, for he returned to the world what might well represent the oldest surviving account of heaven on earth.

Yet did this tradition have a separate existence outside of the Kharsag tablets? And did these also lead back to the mountains of Kurdistan?

The Search for Dilmun

Eden and Kharsag are not the only names by which the dwellingplace of the gods was known to the Sumerian and Akkadian cultures. There are also legends regarding an alleged mythical paradise known as Dilmun, or Tilmun. Here the god Enki and his wife were placed to institute 'a sinless age of complete happiness', where animals lived in peace and harmony, man had no rival and the god Enlil 'in one tongue gave praise'.58 It is also described as a pure, clean and 'bright' 'abode of the immortals', where death, disease and sorrow are unknown59 and some mortals have been given 'life like a god,60 – words reminiscent of the Airyana Vaejah, the realm of the immortals in Iranian myth and legend, and the Eden of Hebraic tradition.

Although there is good evidence to show that the name Dilmun was directly connected with an island state established at Bahrain in the Persian Gulf by the Akkadian king Sargon of Agade (2334–2279 BC),61 there is also clear evidence to suggest that it was a mythical realm in its own right. For example, there are references to 'the mountain of Dilmun, the place where the sun rises'.62 Since there is no obvious candidate for this 'mountain' in Bahrain, and in no way can this island be described as lying in the direction of the rising sun with respect to Iraq, then it seems certain that there were two Dilmuns.

So where had this mythological Dilmun been located?

A chance, unexpected discovery gave me an answer. Glancing through Mehrdad Izady's authoritative book The Kurds – A Concise Handbook, published in 1992, I happened to see references to a Kurdish tribal dynasty known as the Daylamites, who had established a number of powerful Middle Eastern kingdoms during the medieval period, the most famous being the Buwiiyhids (or Buyids) who reigned between AD 932 and 1062. Having succeeded in taking the important 'Abbiisid caliphate of Baghdad, the Daylamites had pushed forward to establish a Kurdish empire that stretched from Asia Minor to the shores of the Indian Ocean.63

Yet as Izady points out in his book: 'Confusion surrounds the origin of the Daylamites.'64 The main centre of their tribal dynasty had been the Elburz mountains, north of Tehran, where many scholars assume they rose to prominence. Yet if the tribe were to be traced back to pre-Islamic times, and in particular during the rule of the Parthian kings of Persia, between the third century BC and the third century AD, a different picture emerges. Their true ancestral homeland had been a region in north-western Kurdistan named Dilamân, or Daylamân, where their modern descendants, the Dimila (Zâzâ) Kurds still live.65

Dilamân? This sounded a lot like Dilmun.

Could they possibly be one and the same?

The ancient church archives of Christian Arbela (the modern Arbil) in Iraqi Kurdistan, confirm this same geographical location by recording that Beth Dailômâye, the 'land of the Daylamites', was located 'north of Sanjâr', around the headwaters of the Tigris.66 Furthermore, as Izady reveals: 'The Zoroastrian holy book, Bundahishn, (also) places Dilamân . . . at the headwaters of the Tigris, and not in the Caspian Sea coastal mountain regions [author's italics].'67

I could hardy contain myself on reading these words – the Bundahishn, as well as at least one other major Kurdish source, placed Dilamân, the ancestral homeland of the Dimila Kurds, 'at the headwaters of the Tigris'! Quickly I checked the accompanying map and confirmed the worst: 'Dilamân' had been located southwest of Lake Van, close to Bitlis, in exactly the same area that I had placed the Garden of Eden! Quite obviously, these words belonged to different languages and were separated by thousands of years of cultural development in the Near East. This I accepted; however, place-names are one of the few things that can be preserved and reused by successive cultures without major alteration. It was feasible therefore that the indigenous peoples of north-west Kurdistan had not only preserved the original Mesopotamian place-name of Dilmun, but had also adopted it as a tribal title.

Source of the Waters

The links between Dilmun and the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers did not end there. The god Enki, who along with his wife was said to have been the first inhabitant of Dilmun, was seen as god of the Abzu – a vast watery domain beneath the earth from which all springs, streams and rivers have their source. In this capacity he was guardian protector of Sumer's two greatest rivers, the mighty Euphrates and Tigris, which were usually depicted as arched streams of water, either pouring out of his shoulders or emerging from a vase held. in his hand. Fish are depicted swimming up these streams, like salmon attempting to reach the source of a river.68

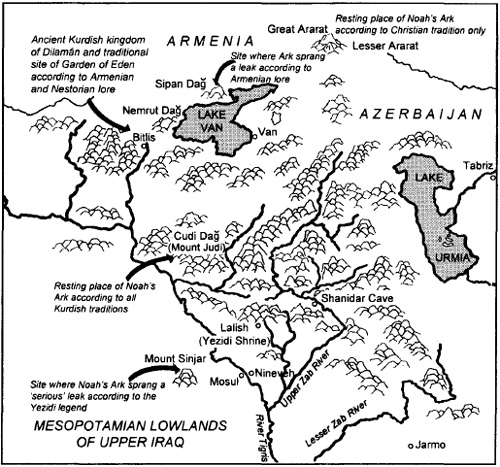

Map 3. Eastern Kurdistan, showing the traditional locations associated with both the Garden of Eden and the Ark of Noah.

As sacred guardian of these two rivers, Enki would have been seen as the protector of the river's sources. In this way, he would undoubtedly have been associated with the headwaters of these rivers, where both the Christian records of Arbela and the Bundahishn text appear to place the mythical realm of Dilmun, and Hebraic tradition places the Garden of Eden.

The principal religion of the Dimili Kurds is Alevism, the third, and perhaps the most enigmatic, of the Kurdistani angel-worshipping cults. Most of its adherents now live around the foothills of Turkish Kurdistan in eastern Anatolia. There is, however, one last bastion of Alevi tribesmen still surviving amid a sea of Sunni Islam in northern Kurdistan, and this just happens to be on the south-western shores of Lake Van.69

So who were these mysterious Alevi tribesmen who worshipped the angels?

The Alevis take their name from the word alev, meaning 'fire', an allusion to its great reverence among their faith. Although in its present form Alevism dates only to the fifteenth century AD, its roots stretch back into the mists of time and encompass many diverse influences, mostly Iranian in origin. They are not Muslims, although they do recognize a series of avatars, or divine incarnations, the most important of which is Ali, the first Shi'ite imam or saint. In contrast, Azhi Dahâka is not forgotten by these people, for he features in an important Alevi ceremonial gathering known as the Ayini Jam.70 Among the more obscure ritual customs of the Alevis is an archaic practice in which they insert a sword into the ground in order to communicate with the universal spirit.71 Women are also allowed to participate in all ritual gatherings, particularly the Ayini Jam, something that has laid the Alevis open to accusations of sexual improprieties taking place at such events, which are not open to outsiders.

The Dimili Alevis are also known as the Qizilbâsh, 'the red heads', in reference to their distinctive deep-red headgear, which they adopted in honour of Ali, the son-in-law of Muhammed, who had apparently said: 'Tie red upon your heads, so that ye slay not your own comrades in the thick of the battle.'72

Closing the book, I could hardly believe what I had read. To say I was overawed by these discoveries is an understatement. Had the Daylamite, or Dimili, tribes of Turkish Kurdistan managed to preserve the name of Dilmun, or Dilaman, from the prehistoric age right down to medieval times? More importantly, did the redheaded Alevi tribesmen guard age-old secrets concerning the Watchers' apparent presence in this region? And what of their home territory, south-west of Lake Van – had this really been the location of Dilmun, the Mesopotamian domain of the immortals, as well as Kharsag, the settlement of the Anannage, and Eden, the homeland of the Watchers?

It was a thought-provoking idea, and the circumstantial evidence for Dilmun's placement in northern Kurdistan looked good. Yet, before I moved on, I needed to find out whether any further clues concerning the alleged existence of the fallen race could be traced within the myths and legends left by the ancient city-states of Mesopotamia. I was soon to discover that in ancient Iraq, more than anywhere else, the memory of the god-men who had once walked among mortal kind had lingered far longer than I could ever have imagined.