SHAMAN–LIKE DEMON

Following the disappearance of the Lake Van obsidian traders sometime around 5000 BC, a new culture began to emerge on the plains of ancient Iraq. These were the al-'Ubaid people, or just 'Ubaid, after the mound settlement of Tell al-'Ubaid, some four miles north of the ancient city-state of Ur, where their presence was first discerned by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1922.

Digging into the low mound amid the shimmering heat waves that filled the desert of central Iraq, Woolley was amazed at the apparent ease with which he was able to find evidence of this previously unknown culture that had once dominated the country. Everything lay close to the surface, beneath the soft dusty earth. Painted potsherds were found at a depth of three feet, and then came flint and obsidian tools as well as fragments of 'reed matting plastered with clay mixed with dung or less often, with a mixture of earth and bitumen'.1 This lay upon a hard surface of river silt on which the incoming tribes had erected their primitive structures of 'reed plastered with clay',2 close to the flooded marshlands of the Lower Euphrates. Indeed, there is every reason to suggest that these people were the distant ancestors of the much-troubled Marsh Arabs of modern-day Iraq.3

Woolley could never have guessed at the immense importance of these fairly insignificant-looking finds, for in the years to come they would provide the missing link between the neolithic explosion in the Kurdish highlands and the spread of civilization and kingship right across the Fertile Crescent of ancient Mesopotamia.

Around 5000 BC the 'Ubaid people descended from the Upper Zagros mountains to take over various existing sites of occupation throughout Upper Iraq.4 They then spread gradually southwards to establish new communities, including the one at Tell al-'Ubaid, c. 4500 BC. Many of their sites of occupation were inherited from an earlier, more advanced culture known as the Samarra, who had been the first to introduce land irrigation and agriculture to the region. The Samarra had also been behind the establishment of Eridu, the first Mesopotamian city, in around 5500 BC. In one temple complex dated to this early period, evidence of a ritual pool and large quantities of fish remains have been unearthed, leading scholars to suggest that the Samarra's principal deity was a primordial form of Enki, the much later Sumerian god of Abzu, the watery abyss,5 who subsequently became divine patron of Eridu.

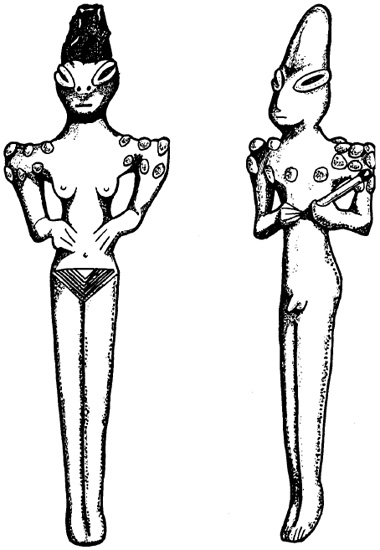

So far there was nothing to suggest the presence of the Watchers among these precursors of the Sumerian civilization. Vivian Broman Morales had, however, spoken of the 'Ubaid culture's strange 'lizard goddess figures', which she compared with the ophidian, or serpentine, clay heads found by Robert Braidwood and his team at Jarmo in Iraqi Kurdistan. These 'lizard goddesses' I had found depicted in various books that featured the art of the 'Ubaid culture. They took the form of strange anthropomorphic figurines, either male or female (although mostly female), with slim, well-proportioned naked bodies, wide shoulders, and strange reptilian heads that scholars generally describe as 'lizard-like' in appearance.6 These show long, tapered faces like snouts, with wide slit-eyes – usually elliptical pellets of clay pinched to form what are known as 'coffee-bean' eyes – and a thick, dark plume of bitumen on their heads to represent a coil of erect hair (similar coils fashioned in clay appear on some of the heads found at Jarmo7). All statuettes display either female pubic hair or male genitalia.

Each 'Ubaid figurine has its own unique pose – some female statuettes stand with their feet together and their hands on their hips. At least one male figurine has its arms horizontally placed across its lower chest area and holds what appears to be a wand or sceptre in its left hand; plausibly a symbol of divinity or kingship. The figurines also appear with several oval-shaped pellets of clay covering their upper chest, shoulders and back. These almost certainly represent beaded chains of office.

By far the strangest and most compelling of the reptilian statuettes is a naked female who holds a baby to her left breast. The infant's left hand clings on to the breast, and there can be little doubt that it is suckling milk. It is a very touching image, although it bears one extremely chilling feature – the child has long slanted eyes and the head of a reptile. This is highly significant, for it suggests that the baby was seen to have been born with these features. In other words, the 'lizard-like' heads of the figures were not masks, or symbolic of some animalistic god-form, but abstract images of an actual race believed to possess reptilian features.

Fig. 13. Two examples of the strange 'lizard'-like figurines found within graves in Iraq and belonging to the 'Ubaid culture, c. 5000–4000 BC. Evidence suggests they may be abstract representations of Edimmu, the much-feared vampires whose origins are perhaps based on distorted memories of Watcher descendants known as Nephilim.

In the past these 'reptilian' figurines have been identified by scholars as representations of the Mother Goddess8 – a totally erroneous assumption, since some of them are obviously male – while ancient astronaut theorists such as Erich von Däniken have seen fit to identify them as images of alien entities.9 In my opinion, both explanations were attempting to bracket the clay figurines into popular frameworks that are insufficient to explain their full symbolism. Furthermore, since most of the examples found were retrieved from graves, where they were often the only item of any importance, Sir Leonard Woolley had concluded that they represented 'chthonic deities' – that is, underworld denizens connected in some way with the rites of the dead.10 In addition to this, it seems highly unlikely that they represent lizard-faced individuals, since lizards are not known to have had any special place in Near Eastern mythology. Much more likely is that the heads are those of snakes, which are known to have been associated with Sumerian underworld deities, such as Ningišzida, Lord of the Good Tree.

So what did these anthropomorphic serpents really signify?

The differences in chronology between the Jarmo heads and the 'Ubaid figurines suggest that this distinctive form of serpentine art had developed in the highlands of Kurdistan as early as 6750 BC before being transferred on to the Iraqi plains around 5000 BC. By this time, however, the art had become somewhat removed from the more basic serpent-like facial features of the much earlier Jarmo heads. The snake had been a major feature among the religious practices of ancient Mesopotamia, where it was identified with divine wisdom, sexual energy and guardianship over otherworldly domains. Furthermore, Armenian folklore, as well as the religions of the Median Magi and the Yezidis of Iraqi Kurdistan, would tend to indicate that worship and veneration of the serpent had remained an important element in the religions of both Iraq and Iran right through till modern times.

This knowledge does not, however, explain why the 'Ubaid culture should have needed to place serpentine figurines in the graves of its dead. Ritual practices are often born out of fear and superstition, so might they have believed that something awful would happen to the deceased if these statuettes were not placed in the graves? If so, then what was it they so feared might happen to them? And why use obvious serpent imagery? And what sort of serpents might they have been? Those that slither along the ground, or those that walk into a community, breed fear among the inhabitants and take away men and women for their own purposes – if, that is, we are to believe the Hebraic accounts of the fall of the Watchers and the plight of the Nephilim. Might the use of these serpent figurines have developed as a direct result of the crosscontact between the Watcher culture of the Kurdish highlands and the neolithic communities of the Iraqi-Kurdish foothills, who passed on these superstitious observances to the earliest inhabitants of the Fertile Crescent sometime around 5000 BC?

The 'Ubaid figurines might therefore have been used as goodluck totems against the Watchers' believed influence over the dead. Yet this still did not explain why these people should have needed to protect their deceased in this way. The chances are that the 'Ubaid feared that their dead could become Edimmu, or vampires, even after being placed in graves. If so, then why should they have feared this might happen in the first place?

There were no clear answers. Not as yet.

For a better understanding of the Watchers' possible contact with this primitive culture, we would have to return to the foothills of the Zagros mountains where the 'Ubaid had also left their mark on history.

The Goat-men of Susa

Elam is the name given in the Bible to a country situated in the Lower Zagros region of southern Kurdistan, on the borders between Iraq and Iran. It is a territory known today as Khuzistan. In Genesis 10, Elam is cited as one of the 'sons of Shem', who was himself one of the three sons of Noah.11 Later, during the age of Abraham, it is Chedorlaomer, the king of Elam, who smites the different giant races of Canaan.12 It was also to Elam's capital, Susa, or 'Shushan', that Daniel and many more of the Babylonian Jews journeyed after they were given their freedom by Cyrus the Great, the king of Persia (see Chapter Six). Indeed, Daniel is said to have died here, and the peculiar honeycomb spire that marks his much-venerated tomb still dominates Susa's sedate skyline.

Yet this important stage of Elam's strange history is young when compared to its most distant past. Evidence from early neolithic sites, such as the mound settlement of Ali Kosh, west of the village of Mussian in the Lower Zagros, has shown that this region was occupied as early as the eighth millennium BC.13 Tell-tale signs of the Halaf culture have also been found at these early sites. Despite the presence of these outside influences, the land of Elam would seem to have possessed its own unique religious ideals and artistic style, which persisted across the millennia.

It was around 5000 BC, however, for a period of anything up to a thousand years, that the 'Ubaid culture held sway in Elam.14 Archaeological excavations from the final phase of their influence have revealed a large variety of unique stone stamp seals of a highly shamanistic nature.15 Each depicts what the scholars have described as an anthropomorphic 'goat-headed demon', with incised marks on its body to signify body hair and its arms raised out and upwards. These totemic figures are intriguing in their own right. It is, however, the imagery that accompanies them that is of special interest, for in one instance the figure appears to be controlling serpents; in another a serpent passes behind the goat-man; and in a third, the figure appears to be controlling two huge 'birds of prey'16 that rise up towards its body.

As I looked at the seals I realized that the 'goat-headed' demons of the archaeologists were very probably goat-men, or goat shamans. The snakes perhaps represented the supernatural potency attached to these shamanistic characters, while the 'birds of prey' seemed almost certain to be vultures. The raised position of the goat-men's arms implied control and manipulation of these animalistic forces. Once again the link between goats, snakes and vultures in Near Eastern mythology had been demonstrated.

Fig. 14. Three stamp seals from the 'Ubaid or proto-Elamite culture of south-western Iran showing anthropomorphic goats controlling serpents and vultures. Do these goat 'demons' preserve some memory of the advanced shamanistic culture thought to be behind the accounts of angels and Watchers in Judaeo-Christian tradition?

That vultures, and not 'birds of prey' in general, are depicted on the stone stamp seals is dramatically confirmed by the knowledge that the peoples of Susa, c. 3500 BC, regularly practised exposure of the dead.17 Although this form of burial was not usual for the 'Ubaid culture of ancient Iraq and Iran, it is by no means inconceivable that they, too, practised excarnation. The culture's connection with the Marsh Arabs of Lower Iraq is a tantalizing link here, for the indigenous religion of this culture is Mandaean, which also practised exposure of the dead in ancient times.18 Furthermore, decorated pottery dated to the earliest phases of proto-Elamite history is decorated with clear vulture imagery.19

Might these 'Ubaid stamp seals have some bearing on the goat and vulture shamanism thought to have taken place at the Shanidar cave on the Greater Zab, c. 8870 BC? I felt the answer was undoubtedly yes, for they appeared to confirm that the 'Ubaid settlers of Elam must have been heavily influenced by the shamanistic activities taking place in the Upper Zagros, and I was not alone in thinking this way. In an important paper entitled 'Seals and Related Objects from Early Mesopotamia and Iran' published in 1993 in a book entitled Early Mesopotamia and Iran – Contact and Conflict c. 3500–1600 BC, Edith Porada of Columbia University, New York, discusses the Susa stamp seals. She then goes on to outline the discovery by Ralph and Rose Solecki of the goat and bird remains inside the Shanidar cave. After careful assessment of the evidence, she concludes that:

. . . the evidence . . . suggests that there was an early concept of a creature or creatures, which combined the features of goat and powerful bird in a manner unknown to us; that the human figure with the horned animal head on stamps of the Ubaid period was a powerful, shaman-like demon capable of warding off serpents.20

What did she mean by 'a powerful, shaman-like demon capable of warding off serpents'? What sort of solution was this?

'Shaman-like demon' does not appear as an entry in standard encyclopaedias. I could only suppose that these shaman-like demons were synonymous with the goat and vulture shamans of Kurdistan, who were themselves synonymous with the bird-men, goat-men and walking serpents of Enochian and Dead Sea tradition. In other words, by 'shaman-like demon' she had in fact been alluding to the proposed Watcher culture.

In prehistoric Susa it was the Watchers' goat-like aspects that would appear to have been best preserved in visual art, but elsewhere in the ancient world it would seem to have been their connection with the vulture that became the mainstay of early religious iconography. In Yezidi and Yaresan tradition they were personified as the Ancient One, the Peacock Angel, and as the black serpent Azhi Dahâka or Sultan Sahâk. In Sumeria they were mythologized as bird-men and serpent gods such as Ningišzida, while elsewhere in the Near East the vulture attributes of the Watchers became the ultimate symbol of the Great Mother, particularly in her aspect as the goddess of death and transformation.21

Constantly archaeologists have unearthed stylized goddess figurines from the neolithic age with abstract bird-like qualities, such as long beaks, short wing-like arms and wedge-shaped tails. These have been found in such far-flung places as Crete, Cyprus, Syria, mainland Greece, in the Balkans and Danube basin of eastern Europe, at Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley and as far east as Baluchistan in central Asia.22 Many also possess strange, slit-like eyes, like those of the serpentine clay heads found by Robert Braidwood and his team at Jarmo in Upper Iraq.

In time the individual components of the vulture shamans would appear to have separated out to become abstract symbols in their own right. For instance, in a burial site at Tel Azor, about four miles from Jaffa, in Israel, around 120 fired clay ossuaries (or boneboxes) were discovered grouped together in a cave. Many have beaked noses on raised front ends and wedge-shaped backs, and each contained the denuded bones of individuals who had been subject to excarnation after death.23

Fear of the Evil Eye

Eventually all traces of the vulture itself were completely lost, leaving only specific abstract symbols to signify the age-old potency of this great bird of death and transformation. Feathers, as I had already established, had been used to ease childbirth, ward off snakes and heal wounds, while its eyes would appear to have suffered a much worse fate. For instance, in a Sumerian tablet from the city-state of Lagash dated to the third millennium BC, it speaks of the 'divine black bird' of the 'terrible eye'.24 D. O. Cameron in his important work Symbols of Birth and of Death in the Neolithic Era was certain that this referred to the large black pupil and contrasting white iris of the vulture, and had concluded that:

. . . in the process of time the original meaning of the vulture symbol [i.e. its eye] also became obscured. It was replaced by a kind of apotropaic magic, whereby a person could avoid harm by wearing a charm which was protective – in this case another eye which could outstare the eye of death . . .25

So the eye of the vulture eventually became the evil eye. In Kurdistan charms against the evil eye would invariably be cowrie shells,26 a significant choice since they closely resemble the pinched 'coffee-bean' eyes of the Jarmo heads, which, I feel, went on to influence the development of the neolithic bird goddess figurines found throughout the Middle East. If true, it seems certain that belief in the evil eye may well have begun at places such as Jarmo in the Kurdish highlands because of its community's apparent contact with the proposed Watcher culture.

It was intriguing to think that this power attributed to the evil eye might well have originated, not from the vulture -or, indeed, from the snake – but from a memory of those who had once borne these animalistic features. Was it possible that the Watchers' compelling eyes, said to have been 'like burning lamps', were responsible for the development of this age-old superstition? Perhaps the Watchers, these bird-men with viper-like features, were seen to have possessed hypnotic qualities similar to those accredited to the serpent. One can almost imagine the inhabitants of a primitive farming community, such as Jarmo, averting their eyes from the stern-faced Watchers in the belief that their hypnotic gaze could control a person's free will.

If the Watchers really had walked among mortal kind, then the memory of their existence would appear to have become more and more abstract as the millennia rolled on. By the time these traditions entered Judaea following the Babylonian Captivity of the Jews in the sixth century BC, the memory of this ancient shamanistic culture had become mythologized as angels, fallen angels, Watchers and bene ha-elohim, the Sons of God.

Already present in Palestine had been a clear belief in the existence of 'those who had fallen', the Nephilim, as well as a strong cult of the Great Mother, in her aspect as the vulture of death. Abstract bird symbols appear frequently in early Canaanite art, and sometimes these seem to have been combined with strong serpentine imagery as if to bring together these two quite disparate traditions of Nephilim and Great Mother. One perfect example of this strange fusion is a one-and-a-quarter-inch-high copper figurine officially identified as 'a Canaanite god, c. 2000 BC'.

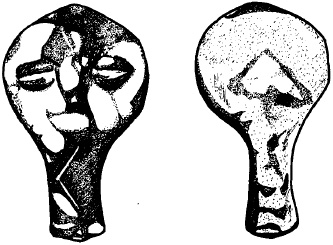

This item, now in the author's personal collection, possesses a long serpentine neck, cut with a deeply incised zigzag. Its 'human' head is shaped like the hood of a cobra – the termination of which is curled over to form a kind of snake headdress. On the inside of the cobra hood is a three-dimensional human face, composed of a bird beak, a tiny mouth and two distinctive 'coffee-bean' eyes, like those found on the Jarmo heads. Blended together here, whether by accident or design, were some of the most important abstract symbols of the fallen race. Furthermore, the zigzag is an indisputable serpentine symbol,27 while the stalk-like neck is indicative of the long-necked Anakim, the supposed progeny of the Nephilim who inhabited the land of Canaan in prehistoric times.

Fig. 15. Canaanite 'god' cast in copper, c. 2000 BC. The cobra hood, beaked nose, 'coffee bean' eyes and long neck, inscribed with a serpentine zigzag, are all characteristic symbols of the Nephilim, the name given to the fallen race by the earliest Israelites.

This small figurine is the closest I have ever come to finding a representation of a Nephilim giant – or at least their abstract memory, which appears to have been preserved in ancient Canaan more strongly than anywhere else in the Middle East. Little could the Babylonian Jews returning from the Captivity have realized just how much of an impact the revitalization of these age-old myths of the fallen race would have upon the face of world religion over the next 2,500 years of human history.

I had put forward the theory that the fall of the angels recorded in Enochian and Dead Sea literature referred to the trafficking between two quite different human cultures – one of a highly evolved nature living in a highland region referred to as Eden or Kharsag, and the other a more primitive culture living in the surrounding foothills and plains. The great wealth of circumstantial evidence suggested that this solution had at least some basis in truth, and that the homeland of these so-called 'angels' or 'Watchers' had been northern Kurdistan, very possibly on the southern shores of Lake Van. The vulture shamanism conducted at the Shanidar cave, c. 8870 BC, as well as the serpentine clay heads fashioned at Jarmo, c. 6750 BC, and the 'lizard-like' figurines and stone stamp seals of the 'Ubaid culture, c. 5000–4000 BC, were all tantalizing evidence to this effect.

There were, of course, many unanswered questions. For example, if the Watchers had once existed, then where did they come from? Were they indigenous to Kurdistan, or had they migrated there from some foreign land? What was the nature of the cataclysms that had supposedly destroyed the Nephilim at the time of the Great Flood, and when exactly had these taken place? And, more pressingly, how on earth did the highly advanced and unique Çatal Hüyük culture fit into the picture? I quickly realized that, by answering the final question first, I could begin to unravel the other great mysteries still attached to the origins of the fallen race.