FATHER OF TERRORS

Beyond the city lights of Cairo, the bus navigated its way through exhaust-drenched streets, packed with hooting cars, beaten donkeys, Coca-Cola signboards and young Egyptians on mopeds. It was dark, and somewhere well beyond the run-down suburbs the crowded vehicle came to a halt in a busy road, alive with nocturnal activity.

Not knowing where on earth I ought to be heading, I passed along a narrow street filled with a selection of low-key souvenir shops. The path seemed to climb higher and higher – the rising plateau now visible before me. Reaching a certain point, I glanced up to see one of the most breathtaking sights of my life – the Great Pyramid and its two accompanying neighbours soaring upwards like colossal giants, higher than anyone could ever have prepared me for. Bright lights illuminated their awesome, silhouetted forms, while all around the trackway leading to their base were literally hundreds of stallholders, camel handlers, street peddlers and security men. It was a sight I shall never forget.

The Pyramids of Giza symbolize everything that ancient Egypt stands for in the minds of the world today: advanced technology, immense building capabilities, exact geodesy, precision geometry and astronomical knowledge far exceeding that of any other contemporary culture. Egypt's history alone is enough to conjure up some of the most vivid and romantic images the world has known. Cleopatra, Nefertiti and the boy king Tutankhamun – this is how almost everybody imagines this ancient kingdom, but what of its reality? Where does the romance stop and the truth begin?

The age of the Pharaohs began in earnest around 3100 BC1 with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, and the rule of a joint kingdom by one king. Narmer and his successor Hor-aha established what is known to Egyptologists as the Archaic Period – that is, Dynasties One and Two. With the commencement of the Third Dynasty, c. 2700 BC, there came an era known as the Old Kingdom, an age marked by the sudden urge among the Egyptians to begin building pyramids – an idea inspired by the necessity to find a way of preserving the physical body of a dead Pharaoh, and thus ensuring the immortality of his soul in the afterlife. The mighty step pyramid of Sakkara, built for the Pharaoh Djoser, or Zoser, was the first to be undertaken around 2650 BC.

Ever grander pyramids were built along the western banks of the river Nile, until the construction during the Fourth Dynasty, c. 2620–2481 BC, of the Old Kingdom's greatest ever achievement – the Great Pyramid. At 756 feet across each baseline, 481 feet in height, and covering an area of just over 13 acres,2 it is probably the finest piece of workmanship human hands have ever produced, yet, despite this, its history and ownership are contradictory and vague. When the hired workmen of the Arab Caliph Al-Ma'moun finally broke into the Great Pyramid after weeks of tunnelling through its solid limestone blocks in AD 820, they came across its famous granite sarcophagus in the King's Chamber. This lidless stone box was said to have contained 'a statue like a man (i.e. a body-shaped coffin), and within it a man, upon whom was a breast-plate of gold set with jewels', while 'a sword of inestimable price' and 'a carbuncle (a precious red stone, probably a ruby) of the bigness of an egg' lay beside the corpse.3

Despite the fact that this account was first recorded during Al-Ma'moun's own lifetime,4 archaeologists and pyramidologists alike tend to dismiss these discoveries as complete fantasy. So what might Ma'moun's workmen have actually discovered? The body of its builder? Or the remains of some much later interment?

In ancient times many theories were put forward as to the designer of the Great Pyramid, but only Herodotus appears to have got it right. He spoke of its builder as one Cheops, the Greek rendering of a Fourth Dynasty Pharaoh named Khufu, who reigned for twenty-three years from c. 2596 BC onwards. This ancient tradition, repeated by later authors, remained unconfirmed until the mid nineteenth century when an English treasure hunter and self-proclaimed Egyptologist, Colonel Richard Howard-Vyse, announced the discovery of quarry marks bearing the cartouche (i.e. the oval-encased signature) of Khufu in a previously unknown relieving chamber, situated above the King's Chamber. Although these marks are generally believed to have been left by quarrymen in around 2590 BC, some people now firmly believe that they were faked on the instructions of Vyse so as to boost his credibility as an Egyptologist.5

No one really knows for sure why the Great Pyramid – or its two neighbouring pyramids, one assigned to Khufu's son, Khafre, the Greek Chephren, c. 2550 BC, and the other attributed to Khafre's own successor, Menkeure, the Greek Mycerinos, c. 2500 BC – was actually built. Hundreds, if not thousands, of books have voiced their often conflicting opinions as to its true purpose. Although it might well have acted as a tomb for its founder, it also probably played a major role as a place of funerary rites and rituals associated with the journey of the soul of the Pharaoh in the afterlife. Other theories have suggested that the Great Pyramid acts as a giant celestial clock highlighting the actions of the sun's yearly course, and that its angles, measurements and geometry bear a geodesic relationship to the actual size, movements and axis of the earth. All theories are at least partially correct.

It was not, however, just the Pyramids that I wanted to see tonight. Hiding among the broken temples and tomb structures, off to the left of the Second Pyramid, was Giza's other great prize. It was not the most easy monument to find in the dark, but away from the path, beyond the low fences, I confronted the deeply scarred, noseless face of the Great Sphinx. The eerie overhead glow made by the street-lights of nearby Cairo only partially illuminated its visible head and long flat back. Its long front paws, its belly and curled tail remained under a blanket of darkness that covered the deep rectangular enclosure hewn out when the monument was constructed by ancient hands.

For too long I gazed up at its motionless visage that extended from the huge nemes-headdress. According to all orthodox sources, this mysterious edifice had been carved from the living rock on the eastern edge of the Giza plateau, sometime around 2550 BC. It is said to be 240 feet long, 66 feet high, and some 36 feet broad at the shoulders. The Sphinx was made at the request of Khafre, the believed builder of the nearby Second Pyramid. The monument's face, they say, is the likeness of Khafre. A life-size statue of this Pharaoh, with a visage that bears a close resemblance to that of the Sphinx, was discovered hidden in the nearby ruins of the so-called Valley Temple, constructed from the huge white limestone blocks extracted from the deeply cut enclosure.

The Egyptologists say that the Sphinx has been battered by sandstorms throughout its long history. These have effectively weathered its features and buried it up to its neck on many occasions. A curious tale is told of how a young prince named Thutmose experienced a very strange dream after falling asleep against its towering head, the only part exposed above the desert sands. In his slumber the spirit of the Sphinx told him that if he cleared away the sand that was choking it to death, then it would ensure that one day he would become Pharaoh. Enthused by this loaded offer, the prince respectfully did what was asked of him and, as a consequence, the Sphinx kept its side of the bargain, enabling the prince to ascend to the throne as Thutmose IV in c. 1413 BC. To commemorate this event, the Pharaoh had an inscribed stone slab, or stela, erected between the Sphinx's long paws, and here it has remained to this day.

In time the Sphinx was once more covered up to its neck in sand, and even though the Romans dug it out again during their own age, the body was to remain hidden by the desert almost permanently, thus preserving its carved features for future generations. It was said that in 1380 a Muslim fanatic named Saim el-Dahr became so incensed by the attention being paid to this pagan monument that he deliberately cut off its nose!6 Adding to its misery is the knowledge that European travellers chipped off fragments from the Sphinx's carved face and lips, which they took away and used as lucky charms. Worse still, the Mameluke Turkish guards are alleged to have used the Sphinx's head for target practice!

Only in 1816, when excavations were conducted around its base for the first time, was it realized that the Sphinx had once borne both a stone crown and a beard, and that its face had at one time been painted red. Even so, it was not until the 1930s that an Egyptologist, Dr Selim Hassan, undertook to rescue the stone monument completely from the sands for the first time since Roman times. Hassan made many important discoveries during his excavations, including the fact that the Sphinx had been the subject of a special cult and royal pilgrimages throughout the New Kingdom period, c. 1308–1087 BC. What, then, did this huge recumbent stone monument mean to the ancient Egyptians?

Horus and the Horizon

The Great Sphinx faces directly towards the eastern horizon where the sun rises at the spring and autumn equinoxes – the midway markers in the solar cycle which currently fall around 21 March and 22 September each year. Mythically speaking, the leonine monument has many identities and functions, although first and foremost is its association with Hor-em-akhet, Horus-in-the-Horizon, and Hor-akhty, Horus-of-the-Horizon, both forms of the sun god Horus. In this capacity the Sphinx was equated with a leonine beast called Aker, which was said to guard the entrance and exit of the underworld tunnels through which the sun god travelled each night in the form of a divine falcon after setting on the western horizon. The role played by Horus in this myth cycle was originally assigned to the sun god Re, in his form as Atum, 'the Complete One',7 or Atum-re, who, as the setting sun, journeys as a bird through the dark caverns of the underworld, only to reemerge at dawn on the eastern horizon as the god Re-harakhty. This original myth was undoubtedly the work of the astronomerpriests of Annu, or Heliopolis, the Old Kingdom's cult centre for the worship of Re, situated in what is today just another fumefilled suburb of Cairo.

The Greek rendering of Hor-em-akhet, Horus-in-the-Horizon, is Harmakhis, the name by which the Sphinx was more commonly known in classical times, and this blatant geomythic connection between the equinoctial sunrise, the double horizon and the Great Sphinx probably accounts for why the Giza plateau was once known as Akhet Khufu, Khufu's Horizon. Other names for the Sphinx were hu, meaning 'the protector'; Khepera, a form of Re as the scarab beetle, and Rwty, or Ruty, 'the Leonine One', who is the fierce guardian and protector 'on the far north of the underworld'.8 In around the year AD 1200, a noted Arab named el-Latif claimed that the great carved lion was known to his people as Abou'l Hôl, the 'Father of Terrors', a connection perhaps with its role as the omnipotent guardian of the Giza plateau.9

Such was the known, accepted story of the Sphinx, but it seemed that certain more left-field scholars had other ideas on its origin – ideas which, if proved to be correct, would mean the world was going to have to rethink everything it had ever been taught about the foundations of the Egyptian civilization.

The Greatest Riddle

Over the years many open-minded individuals have pointed out clear anomalies in respect of the traditionally held views concerning the origins and dating of the Sphinx. For instance, just by looking at the carved face one can see how out of proportion it is to the rest of the head, while the head itself is quite obviously too small when compared against the rest of the body. Another problem has been identifying the Sphinx. Detective Frank Domingo, a New York Police Department senior forensic expert, made a detailed profile study of the monument's face and concluded that it barely resembled Khafre's known features, showing more an African or Nubian Negroid face than an Egyptian Pharaoh.10 Might the monument's present face have replaced a much earlier one of, say, a lion, a god or a goddess perhaps? Remember how in Greek myth the Theban Sphinx that posed the famous riddle possessed a female gender.

A further anomaly regarding the date of the Great Sphinx is the stone stela recording the dream of Thutmose IV, which still rests up against the monument's breast, between its great paws. Towards the bottom of the stela, the lines have eroded heavily, but just visible is Thutmose's praise 'to Un-nefer ... Khaf[re] ... the statue made for Atum and Hor-em-akhet'.11 Interpretation of this line has led to much speculation in Egyptological circles, for it is possible that Thutmose is not praising Khafre for building the Sphinx, but for clearing away the sand from around its body, exactly as he himself had done 1,100 years later. Respected Egyptologists such as J. H. Breasted and Gaston Maspero endorsed this controversial interpretation.12

Adding further weight to this curious enigma is the so-called Inventory Stela found during the mid nineteenth century by the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette (1821–81) in a minor temple dedicated to the goddess Isis, east of the Great Pyramid. It records how Khufu had apparently discovered a temple dedicated to Isis (probably not the same one) 'by the side of the cavity of the Sphinx, or on the northwest of the House of Osiris, Lord of Rosta'. Here the Sphinx is given the name 'Horemakhet . . . Guardian of the Atmosphere, who guides the winds with his gaze'.13 Further on, the text states that the king went on a tour to see the Sphinx and a nearby great sycamore tree struck by lightning -the same bolt that had supposedly severed part of the monument's nemesheaddress (i.e. the back of its head). Since Khufu was Khafre's father, this clearly implies that the leonine monument had already been in place during Khufu's reign. There is, however, a problem, for the white limestone stela – currently in the Cairo Museum – dates only to the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, c. 664–525 BC, i.e. during the Late Dynastic Period, yet it is thought to be a copy of an original Old Kingdom inscription. It should also be remembered that the Egyptians meticulously copied original royal inscriptions and texts, translating them into the textual grammar of the period.

By far the most convincing evidence for the monument's enormous antiquity is the severe erosion clearly visible on the Sphinx's worn body, as well as on the walls of the surrounding enclosure, and on the remains of the Temple of the Sphinx and the nearby Valley Temple. This distinctive weathering shows a subjection to the elements far beyond many of the neighbouring monuments, temples and tombs supposedly constructed at the same time as the Sphinx and its accompanying temples, using the same white limestone.

John Anthony West, a maverick Egyptologist and successful author, was the first person publicly to draw attention to these uncharacteristic weathering effects with the publication in 1979 of his essential work Serpent in the Sky: The High Wisdom of Ancient Egypt. His theory, inspired originally by various observations made by the French mathematician and philosopher, R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz, was that the deep horizontal scars found along the Sphinx's body were caused not by wind and sand erosion, as had always been assumed, but by water.

His arguments for this conclusion were simple.14 For almost all of the past 4,500 years the Sphinx and its accompanying temples have been covered by sand. This means that they would have been protected from the khamsin, or desert wind, which periodically gusts from the south. If the erosion had been caused by wind and sand, then one should expect to find heavier erosion on the south side of the Sphinx. This is simply not the case; the horizontal gullies are evenly placed around the whole of the body. Similar rock erosion can be recognized on cliff faces at Abydos, Luxor and at other exposed locations along the Nile. These effects have been unanimously attributed by geologists to water erosion, caused at a time when heavy rains persisted in ancient Egypt.

Why, then, were almost identical signs of erosion found on the Sphinx?

John Anthony West championed this new interpretation of the weathering on the Sphinx for ten years, although he would have to wait until 1989 before being given the chance to put his water erosion theory to the test. It was in this year that West managed to secure the services of a qualified geologist named Dr Robert Schoch, Associate Professor of Science at Boston University. He holds a doctorate in geology and geophysics, attained at Yale University, and is a specialist in the effects of weather erosion on rocks. Dr Schoch, working under the auspices of West, began an in-depth study of not only the Sphinx but also its rectangular enclosure and the limestone blocks used in the construction of the nearby Sphinx and Valley Temples. After only a relatively short time, the geologist became convinced that the deep horizontal gouges and vertical fissures seen on all these rock-faces, especially the Sphinx itself, were indeed 'classic textbook' examples of water erosion induced by rain precipitation. Evidence of more obvious wind erosion could be seen on nearby Old Kingdom tombs that were dated by conventional Egyptologists to the very same age as the Sphinx, yet this weathering was entirely different. Sand carried by harsh winds scours out softer layers of rock, leaving much harder layers intact. This gives a distinct, sharp profile with evenly spaced pitted areas, entirely unlike heavy rain erosion, which creates a smooth, undulating profile that curves into the rock's softer layers, and also leaves deep vertical fissures as the water flows down the rock surface.

In argument against Schoch's claims, first published in an edition of the speculative Egyptological magazine K M T in the summer of 1992,15 an archaeologist, Mark Lehner, who is considered to be an authority on the Sphinx, argued one major point. He claimed that although the weathering of the Sphinx might well have been caused by water, it had occurred in Old Kingdom times and was simply the result of poor-quality rock being used to carve the monument. He drew attention to the nearby Old Kingdom tombs that had clearly been weathered by wind and sand, and pointed out that these were carved from much harder white limestone. If this were so, then it brought Schoch's theory into serious disrepute. Seizing the opportunity to prove whether Lehner's views were indeed correct, a BBC-backed Timewatch team, who were collaborating at the time with an American production company to screen a documentary on Schoch and West's findings, conducted their own independent survey of the geology around the Sphinx enclosure. They discovered that the sand-beaten tombs of the Old Kingdom were carved from exactly the same rock as the body of the nearby Sphinx.16

Schoch was right and Lehner wrong.

Few Egyptologists have taken up the gauntlet and attempted to shoot down Schoch's discoveries, since very few of them are qualified in the field of geology. Those who have looked into the matter have so far been unable to come up with a suitable explanation for the presence of water erosion on monuments found on the Giza plateau. Furthermore, Schoch received a major boost of confidence when he presented his findings at the 1991 Geological Society of America's convention held in San Diego. This event is a forum to air new ideas in geology, and the delegates are always quick to express their opinions on the lectures presented. Yet not only could they find no obvious flaw in Schoch's thesis, but no less that 275 of the attending geologists offered help with the on-going project!17

So for the moment it was game, set and match to Schoch.

In his published report, Schoch concluded that the Sphinx, its surrounding enclosure, along with the Sphinx and Valley Temples, must have been carved from the limestone bedrock during a period in history when there were sufficient rains to cause such adverse water erosion, and these had not been present for at least five thousand years. After due assessment of the available evidence, Schoch had placed the construction of the Sphinx between 7000 and 5000 BC, during the so-called neolithic subpluvial when it rained almost constantly in the eastern Sahara. In support of his proposals, Schoch pointed out that during this same time-frame protoneolithic communities, such as those at Çatal Hüyük in central Anatolia and Jericho in Palestine, were engaged in sophisticated building projects. These would have necessitated not just individual skills, but communal leadership similar to that which must have been necessary first to remove the huge stone blocks from the enclosure, then to carve the Sphinx as the extracted stone blocks were used to construct the Sphinx and Valley Temples.

Made in the Age of Leo

More recent research has pushed back the age of the Sphinx to at least 10,500 BC, some 2,500 years earlier than the estimations of Schoch and West. A construction engineer and Egyptologist, Robert Bauval, working alongside the investigative journalist and author Graham Hancock, has recently published details of an extensive survey concerning the complex astro-archaeology of the Giza plateau. In their important book, Keeper of Genesis, Bauval and Hancock convincingly demonstrate that the Sphinx's easterly orientation towards the equinoctial sunrise hints at an importance far greater than Egyptologists could previously ever have imagined. They argue that the leonine monument was connected directly with the ancient Egyptians' understanding of precession, a celestial effect produced by the earth as it gently wobbles around its polar axis in a manner quite similar to the way a child's gyroscope or spinning top is seen slowly to sway when revolving at high speed.

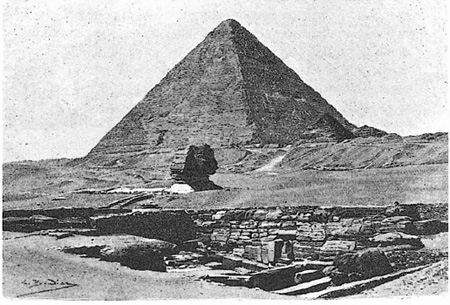

Fig. 17. Nineteenth-century illustration showing the Great Pyramid, the Sphinx and the still half-buried Valley Temple. Does the Giza plateau conform to a precise ground-plan incorporating astro-mythic and geomythic data that preserves the date 10,500 BC? If so, then what do we know about the people who lived during this lost age of humanity?

This gentle wobble of the earth produces various visual effects, the most important of which is the phenomenon known to astronomers as precession. This is where the starry canopy, or firmament, appears to shift its position relative to the path of the sun at a rate of 1° of a 360° circle every seventy-two years. Since prehistoric times, this astronomical cycle has been observed and recorded by noting which constellation rises just before the sun each spring (or vernal) equinox. Twelve major constellations, corresponding to what we know today as the signs of the zodiac, mark this 25,920-year celestial merry-go-round, each one taking a period of 2,160 years to cross the equinoctial sunrise line before being replaced by the next sign, and so on until all twelve have completed a full 360° circle in reverse order – hence the term 'precession', or backwards motion.18 So instead of Capricorn following Sagittarius, or Aquarius following Capricorn, as they do in the conventional yearly zodiac – Capricorn follows Aquarius, Sagittarius follows Capricorn, and so forth. During our current age it is the constellation of Pisces that rises with the sun at the vernal equinox, and soon this will have shifted enough to make way for the constellation of Aquarius to guide us through the next period of 2,160 years; hence the well-known phase 'the age of Aquarius'.

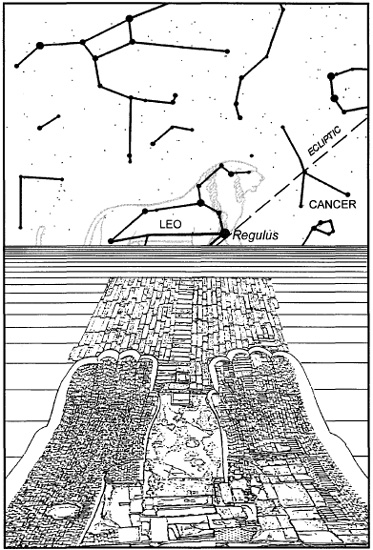

With all this in mind, Bauval and Hancock felt it beyond coincidence that the Great Sphinx should face directly towards the point on the eastern horizon where the current precessional sign appears each spring equinox, just before the sun itself rises. Since the Egyptian astronomer-priests were meticulous in their use of celestial alignments and star-related symbolism, the presence of a leonine creature marking the equinoctial sunrise line would appear to suggest that the Sphinx was constructed at a time when the constellation of Leo rose with the sun on the spring equinox -in other words, during 'the age of Leo'. There is a slight problem to this, however, for the last age of Leo took place between 10,970 and 8810 BC.19

It was an extraordinary theory, and to prove it correct it would be necessary to establish whether or not the ancient Egyptians really were aware of precession, most astronomers assuming that the Greeks developed the idea in the second century BC, through a combination of long-term observations of the celestial sphere and a few, fairly simple mathematical calculations. This may indeed have been the case, but research by an American Egyptologist, Jane B. Sellers, in addition to new findings by Bauval and Hancock, has made it clear that the Egyptians were not merely aware of precession, they also acknowledged its presence in mythical events20 and incorporated its slowly shifting cycle into the design and orientation of the pyramids.21 Furthermore, a connection between the Great Pyramid and the precessional cycle had been suspected as early as the mid nineteenth century,22 while in 1907 an Egyptian scholar and astro-mythologist named Gerald Massey concluded in an extraordinary work entitled Ancient Egypt the Light of the World that the Sphinx's association with the age of Leo had given rise to the monument's mythical connection with both the Aker and Hor-em-akhet, Horus-in-the-Horizon.23 Indeed, Massey had no qualms in asserting that: '. . . we may date the Sphinx as a monument which was reared by these great (Egyptian) builders and thinkers, who lived so largely out of themselves, some thirteen thousand years ago.'24

If the Great Sphinx really was built by an unknown culture during the age of Leo, as Bauval and Hancock assert, then it had been accomplished by a race which possessed an acute knowledge of astronomy and saw an incredible significance in marking out great cycles of time. And as if this were not enough to contend with, then the fact that the huge cyclopean blocks removed from its rectangular enclosure had been used to construct the nearby Sphinx and Valley Temples meant that these people possessed the skill and ability to build colossal edifices at a time when the rest of the Old World was striving to learn the very basics of civilized society. Moreover, if we were to accept this, then these two temples were almost certainly not their only architectural achievements. At the Predynastic cult centre at Abydos in Upper Egypt there is another cyclopean monument sunk deep into the earth and built in exactly the same style as the Giza temples.

Here I am referring to the enigmatic Osireion constructed of massive granite monoliths lined on top with enormous stone lintels. At the base of its central hall is a spring that permits the water-table to flood its lower levels, obviously to give the site an aquatic aspect that was carefully incorporated into its design.25 In this capacity, the Osireion must have functioned very much like the Abzu pool found beneath the pre-Sumerian temple at Eridu in Lower Iraq. The Osireion's presence was remarked upon by the Greek geographer Strabo (60 BC–AD 20), following a visit to Abydos in the first century BC, although confirmation of its existence did not come until excavations began at the nearby temple complex of the Pharaoh Seti I (1309–1291 BC) during 1903. It was not, however, fully exposed until work was resumed at Abydos between 1912 and 1914 by Professor Naville of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Only then did the full extent of this 'gigantic construction of about 100 feet in length and 60 in width' become apparent.26

Fig. 18. Conceptual view from the head of the Great Sphinx along the line of the paws to the eastern horizon as it would have looked shortly before the sun rose on the vernal equinox 9220 BC – the date suggested for a universal deluge by the ninth-century Coptic manuscript entitled Abou Hormeis. The presence of the Sphinx's leonine imagery makes sense only if it was constructed during the precessional age of Leo.

Naville compared the structure's architectural style with that of Giza's Valley Temple, which showed 'it to be of the same epoch when building was made with enormous stones without any ornament'.27 This led him to conclude that it was 'characteristic of the oldest architecture in Egypt. I should even say that we may call it the most ancient stone building in Egypt.'28 Yet the Egyptological community back-tracked on their earlier announcements after excavations recommenced at Abydos under the leadership of Henry Frankfurt between 1925 and 1930. Among the minor finds he made in connection with the Osireion was a cartouche of Seti I on a granite dovetail above the main entrance into the central hall, as well as a few minor finds which linked the Pharaoh's name to the interior of the building. As a consequence, the building was henceforth seen as contemporary with Seti's reign.29

The likelihood that Seti I had incorporated this archaic structure, devoid of any other inscriptions, into his own temple complex, probably because of its immense antiquity and sanctity, was never even considered by the Egyptological community. Only Margaret Murray, the anthropologist and Egyptologist who helped to uncover the Osireion during the early stages, remained convinced that its great stone blocks were 'of the style of the Old Kingdom', c. 2700–2159 BC, and that the decoration was added later by Seti. In her opinion, this strange structure with its own reservoir was built 'for the celebration of the mysteries of Osiris', who is probably Egypt's oldest deity.30

A similar controversy has surrounded the dating of the enigmatic Valley Temple. Because a single statue of Khafre and a lone cartouche were discovered within its enormous granite interior, it has been credited to the reign of Khafre, c. 2550 BC, and is therefore seen as contemporary with the construction of the Second Pyramid. Yet there seemed every good reason to place the limestone outer walls (but not the granite interior) of this weatherbeaten structure in exactly the same time-frame as the Sphinx itself – in other words, it was at least 10,000 years old. A similar age would therefore have to be attributed to the Osireion at Abydos.

Quite naturally the Egyptologists can never accept such an immense antiquity for any man-made structure, for to do so would mean disregarding everything they have stood for in respect of Egyptian history. This is despite the fact that some of their pioneering predecessors were far more open-minded in this respect.31

Yet such distant dates are not so incredible as they may at first seem. By 7500 BC the protoneolithic inhabitants of Jericho had constructed a huge stone tower amid colossal fortifications that included a deep, rock-cut ditch. Jericho, it should be noted, is only three hundred miles from Giza.

Personally, I have no problem with accepting the possibility that the Sphinx, as well as the Sphinx and Valley Temples and the Osireion at Abydos, might well constitute the last remaining evidence of an elder culture that had thrived in Egypt sometime between 10,970 and 8810 BC, during the last age of Leo. Yet just accepting this proposal still told me little about the people behind these monuments. Neither did it tell me whether this mysterious race could have had any tangible link with the underground cities of Cappadocia, or the proposed Watcher culture of Kurdistan. All I had established so far was that evidence of long-headed individuals of great stature, who had belonged to an aristocratic group, had been found among the Predynastic cemeteries excavated at Abydos by Jacques de Morgan in 1897, and that these matched anatomical remains unearthed at the earliest Sumerian grave-sites. Could it be possible that representatives of this elite race had been responsible, not only for the construction of Giza's leonine time-marker, as well as the country's cyclopean stone structures, but also for the initiation of the much later neolithic explosion in Kurdistan and the foundation of the earliest city-states of Mesopotamia?

Whoever the Sphinx builders were, they undoubtedly possessed architectural and engineering skills far beyond the capabilities of almost every culture that came afterwards, save perhaps the builders of the Fourth Dynasty pyramids (the construction date for which must remain fixed in this time-frame unless any new evidence suggests otherwise). Some of the stone blocks used in the building of the Valley Temple are 200 tons apiece,32 arid if it is borne in mind that there is hardly a crane today that could lift such a weight, then some idea of the effort needed to move extraordinary blocks of this size suddenly becomes apparent. This does not, of course, mean that such feats of engineering were impossible, only that this style of building construction was highly unusual for any period of Egyptian history.

What more could I learn about the ultimate destiny of this lost culture? There were very few strands to work with, other than the overt astronomical data that these people had evidently encoded into the Giza plateau itself, and this conspicuously proclaimed one specific time-frame – the age of Leo. What made this epoch so important to them, and why construct such an obviously leonine structure to mark a particular precessional age? Surely this advanced culture had not simply sculpted the Sphinx for devotional or ritualistic purposes alone. Why leave such a legacy to future humanity?

Egypt's elder culture was no longer around to provide me with any answers. It was possible, however, that they had passed on the real significance of the age of Leo and the true purpose of the Sphinx in allegorical stories that had been told around camp-fires until they were finally set down in written form during ancient times. Of course, they would by then have become highly abstract and distorted, yet a kernel of truth must have remained within them, and it was this that I needed to extract to discover the ultimate fate of those who had built the Great Sphinx.