KOSMOKRATOR

When the earth was a little younger, Saurid Ibn Salhouk, the king of Egypt – who lived three hundred years before the Great Flood – found that his slumber was constantly being disturbed by terrible nightmares. He saw that 'the whole earth was turned over', its inhabitants too. He saw men and women falling upon their faces and 'stars falling down and striking one another with a terrible noise'.1 As a consequence, 'all mankind took refuge in terror'.2

These nightmares continued to trouble the good king, but for some time he concealed them, without telling another soul what he had seen. Finally, after one further night of misery, he summoned his chief priests, who came from all the provinces of Egypt. No less than 130 of them stood before him, the chief among them being the learned Almamon, or Aclimon.3

King Saurid related every detail of his curious nightmare, and before they offered their own opinions concerning this strange portent, each one consulted the altitude of the stars.4Upon returning they unanimously announced to the worried king that his nightmare foretold that first a great flood would cover the earth. Then a great fire would 'come from the direction of the constellation Leo'.5They assured him, however, that after these disasters 'the firmament would return to its former site'.6

'Will it come to our country?' the king asked.

They answered him honestly. 'Yes,' they said, 'and it will destroy it. '

Having accepted the future fate of his kingdom, Saurid decided that he would command the building of three wondrous pyramids as well as a very strong vault. All these were to be filled with 'the knowledge of the secret sciences', which included everything they had learned of astronomy, mathematics and geometry.7All this knowledge would remain concealed for those who would one day come and find these secret places.

This was the story recorded by various Arab and Coptic historians, including Ibn Abd Alhokm, who lived in the ninth century, and Al Masoudi, who died around AD 943; the latter having included it in his book Fields of Gold – Mines of Gems.8 These accounts have no obvious equivalents in ancient Egyptian literature, while the king, Saurid Ibn Salhouk, has proved impossible to trace. He is not one of the Pharaohs accredited with having built the Pyramids of Giza during the Fourth Dynasty of Egyptian history.

The statement implying that 'the whole earth was turned over' – 'twisted around'9 in one version – is teasingly significant. If the story does preserve some kind of allegorical representation of actual events, then these words clearly bore out Hapgood's idea of a shift in the earth's axis, leading to global catastrophes of the sort described in the tale. More intriguing, however, was the reference to the final cataclysm coming from 'the direction of the constellation of Leo.'

What could this possibly mean?

On an initial reading of this statement, one is tempted to imagine some kind of astronomical body, an asteroid or comet perhaps, breaking up on entry into the earth's atmosphere before raining down a shower of gaseous fireballs that consume everything in their path and leave a trail of death and destruction in their wake. Perhaps this is indeed what happened. More likely, however, is that this reference to a great fire coming specifically from the constellation of Leo relates, not to the area of the firmament where the constellation is placed in the sky, but to the time-period in which these events took place – in other words, during the age of Leo. This deduction would be completely in keeping with the geological upheavals and climatic changes now believed to have occurred during the eleventh, and possibly even right down to the tenth millennium BC.

There is also further tantalizing evidence of this specific link between the era of cataclysms and the precessional age of Leo. In a Coptic Christian manuscript translated into Arabic during the ninth century, entitled Abou Hormeis, it records that: 'The deluge was to take place when the heart of the Lion entered into the first minute of the head of Cancer.'10 The 'heart of the Lion' was the. name given in classical times to the star Regulus, Leo's 'royal star', which lies exactly on the ecliptic, the sun's perceived daily path through the sky. Since the constellation of Cancer follows Leo only in the precessional cycle (Leo follows Cancer in the yearly cycle), then this appears to confirm that these legends preserved, not just the memory of actual historical events, but also the time-frame in which they occurred.

At my request, electronics engineer Rodney Hale punched the astronomical information contained in the Abou Hormeis account into a computer using a Skyglobe 3.5 programme. With some degree of accuracy, he discovered that the last time Leo's 'royal star' would have risen and been visible on the eastern horizon just prior to the equinoctial sunrise was around 9220 BC.11 When the star Regulus, the 'heart of the lion', no longer rose with the sun on the vernal equinox, this would have been seen by the astronomer-priests of Egypt as a signal that the age of Leo had come to an end, and that the age of Cancer was either about to commence or that it had already entered its 'first minute' of arc across the sky.12 This information therefore suggested that the ninth-century Coptic manuscript was implying that a major deluge had occurred in the Middle East, either around or shortly after this date.

If all this was correct, then it seemed likely that Egypt's elder culture had come to associate the age of Leo with the aforementioned global catastrophes. Was it possible, therefore, that besides acting as a marker and guardian of the Giza complex, the Sphinx had been carved by these people as a firm reminder of the great cataclysms that took place during this troublesome epoch of human history? Might this also account for why the leonine guardian of the Giza plateau gained the title 'Father of Terrors'?

The Terrible Eye

Another possible insight into this perplexing mystery may be found in the myth cycles associated with the Egyptian goddess Sekhmet. She is described as 'the Mighty Lady, Mistress of Flame', and is depicted in Egyptian art with the head of a lion and the body of a woman. According to legend, Sekhmet is said to have had the power of the 'fierce scorching, and destroying heat of the sun's rays'. In one account she

took up her position on the head of her father Ra (or Re), and poured out from herself the blazing fire which scorched and consumed his enemies who came near, whilst at those who were some distance away she shot forth swift fiery darts which pierced through and through the fiends whom they struck.13

These passages are taken from the account of how Ra the sun god attempted to destroy humanity, because it saw him as 'too old', and as a consequence turned its back on his faith. In vengeance, the sun god summoned all the gods and asked them to assemble at the place where he 'performed creations'. He also told them to bring with them his terrible 'Eye', who was the goddess Sekhmet (sometimes named as Hathor). He then addressed Nu, the leader of the assembled gods, saying:

'O thou firstborn god, from whom I came into being, O ye gods [my] ancestors, behold ye what mankind is doing, they who were created by thine Eye are uttering murmurs against me. Give me your attention, and seek ye out a plan for me, and I will not slay them until ye shall say [what I am to do] concerning it.'14

Nu had then praised Ra, suggesting that his Eye destroy those who have 'uttered blasphemies against thee'. Yet in response Ra had exclaimed that mankind had already 'taken flight into the mountain'. In due course the Eye 'went forth and slew the people on the mountain'. Yet this slaughter became so terrible that Ra himself had been forced to intervene before the goddess caused the destruction of the entire human race. Sekhmet, however, would not listen, so Ra deposited a mixture of beer, blood and crushed mandrakes all over the earth. The lioness quickly became intoxicated by this powerful brew and as a consequence was unable to complete her mass genocide.15

Later on in the text, Ra summons Geb, the earth god, and tells him to keep watch over the 'snakes' (or worms) who have caused him strife and are in his territory, and that Geb's 'light' should find them in their 'holes', a reference to those who have taken flight and are now seeking refuge in caves and underground caverns. Ra then 'promises that he will give the men who have knowledge of words of power, dominion over them (the snakes), and that he will furnish them with spells and charms which shall draw them from their holes'.16

The idea of the fierce lioness's heavenly fire that consumes the earth is so similar to the events recorded by the Arab and Coptic writers concerning the great fire that came from the constellation of Leo, that the two quite separate traditions may once have shared a common origin. It must also be remembered that the Great Sphinx probably possessed a female gender, bringing these accounts even closer together.

Ra's destruction of the human race might well preserve in highly symbolic form the events which led to the close of the age of Leo. It also suggests that Egypt's elder culture was scattered far and wide as the fiery cataclysms were taking place. The story of how some of these people had first ascended a mountain, only to be blasted by fire, while others had hidden themselves in 'holes', seems to parallel the efforts made by the human race to escape these global cataclysms in folk-tales from other parts of the world. The intoxicating brew that prevented Sekhmet from destroying any more of the human race is surely a reference to some kind of subsequent deluge, perhaps the one that the Coptic Abou Hormeis manuscript said had occurred 'when the heart of the Lion entered into the first minute of the head of Cancer'.

Snakes in the Holes

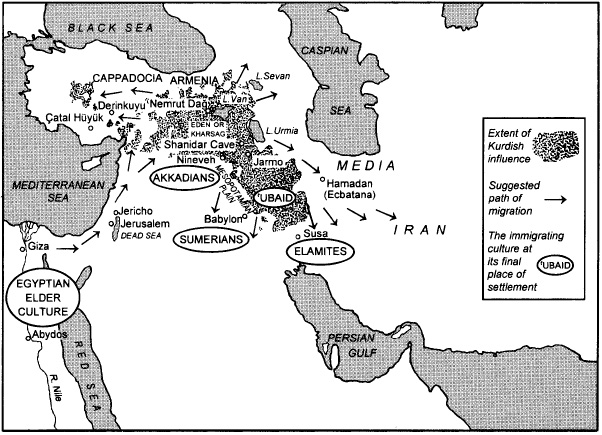

Those who are said to have hidden away from the burning might of the terrible Eye by taking refuge in 'holes' are described as 'snakes'. After the fire has ceased, these individuals are hunted out by the light of Geb and the 'men who have knowledge of words of power', implying that these 'snakes' were not popular in certain quarters for having turned their backs on the cult of Ra. That they attempted to survive, and maybe succeeded in surviving, the onslaught of the devastating Eye by hiding in what would seem to have been underground places is very revealing. Could it be possible that these mixed-up tales are trying to say that at least some of the former inhabitants of Egypt had escaped the global cataclysms by either going underground or ascending mountains? Might some of these 'snakes' have been the inhabitants of the underground cities of Cappadocia, as well as the walking 'serpents' who would seem to have taken up residence in the mountains of Kurdistan, c. 9500–9000 BC? Certainly, the inexplicable shift of early agriculture from its cessation in Egypt, c. 10,500 BC, to its eventual re-emergence in the Kurdish highlands some 1,000 to 1,500 years later, would seem to bear out this migrational movement, whatever its actual causes.

As it stands at the moment, the scattering of Egypt's hypothetical elder culture seems to be the only plausible explanation for the as yet 'uncertain forces' behind the sudden quickening of human evolution in the Near East at the time of the neolithic explosion. They may also have been behind the construction and use of the Cappadocian underground cities, such as the magnificent example at Derinkuyu. If so, their inhabitants were escaping, not just the climatic excesses of the Ice Age, but also the deadly rains of fiery hail, the source of which was very likely to have been the region's active volcanoes. This fear, and perhaps even veneration, of these aerial bombardments was never quite forgotten, and may well have become part of the belief systems of many later cultures of Asia Minor and the Near East, including the Indo-Iranian fire-worshippers and the proto-Hebrews, who preserved this memory of hellfire in the tales of Gehenna, the Valley of Fire.

Once the inhabitants of the underground domains had returned to a more normal state of existence in the outside world, I suspect that some journeyed from Cappadocia into central Anatolia and founded the settlement of Çatal Hüyük, c. 6500 BC. By this time much of the original ancient knowledge brought out of Egypt had been lost or distorted. What little did remain might well have been employed in the making of the extraordinary stone jewellery and highly polished obsidian mirrors unearthed by James Mellaart. Whether the Watchers had themselves been inhabitants of the underground cities before their move to higher ground, or whether they had come directly from Egypt, is uncertain. The memory of Yima's var in Iranian mythology points towards the first solution, which I am personally happy to accept.

Chart3. SUGGESTED CHRONOLOGY OF EGYPT'S ELDER CULTURE AND THE PROPOSED WATCHER CULTURE OF KURDISTAN. The dates are approximate only.

c. 10,500–9500 BC

Decline of Egypt's elder culture during the age of Leo. The construction on the elevated plateau at Giza of the Sphinx monument, the Temple of the Sphinx and the Valley Temple before their eventual abandonment. The cessation of early agriculture by the Isnan Nilotic communities.

c. 9,500–9000 BC

Geological and climatic upheavals accompany the cessation of the Ice Age, including severe volcanic activity and mass flooding; diaspora of Egypt's elder culture to Asia Minor and Kurdistan. Construction of underground cities in Cappadocia to escape the final excesses of the Ice Age.

c. 9000 BC

Establishment of Dilman/Eden/Kharsag settlement around Lake Van in the Kurdish Highlands. This advanced shamanistic culture becomes the angels and Watchers of Judaic tradition, the ahuras of Iranian legend, and the Anannage of Sumero-Akkadian myth and legend.

c. 9000–8500 BC

The Shanidar cave on the Greater Zab is used for shamanistic practices involving goats' skulls, and the wings of bustards, eagles and vultures. Establishment of earliest protoneolithic settlements in Palestine and Syria, particularly at Jericho.

c. 8500–5500 BC

High-point of Watcher culture, which remains in virtual isolation in northern Kurdistan.

c. 6500–6000 BC

Height of Çatal Hüyük culture on the Anatolian plain, practising excarnation and an advanced form of death-trance shamanism that features the vulture. The Jarmo community flourishes in Upper Iraq, its direct contact with the fallen race being preserved as abstract serpentine art.

Gradual fragmentation of the Watcher colony into two opposing camps. One remains in isolation within the Kurdish highlands, while the other emerges on to the surrounding plains of Armenia, Iran and Mesopotamia. This new subculture is variously remembered as the Nephilim of Enochian and Dead Sea literature, the daevas in Iranian mythology and the Edimmu in Assyrio-Babylonian myth and legend. Foundation of first settled communities on the Mesopotamian plains, the earliest being Eridu in c. 5500 BC. Possible time-frame of biblical patriarchs.

c. 5000–4000 BC

The 'Ubaid culture come down off the Zagros mountains of Iraq and Iran to establish themselves at various sites in Upper and Lower Iraq. They inherit the serpentine art of the Jarmo people and, like the Watchers, their totems include the goat, the serpent and the vulture. A 'second' flood strikes the Mesopotamian plains in the form of a series of localized inundations. The memory of these events is confused with much earlier traditions concerning a deluge accompanying the cessation of the last Ice Age, c. 9500–9000 BC. They are remembered as the 'Flood of Noah' by the Yezidis of Kurdistan.

c. 4000–3000 BC

The gradual emergence of city-states on the Mesopotamian plains, perhaps under the influence of the Anannage, the Sumero-Akkadian name given to the Watchers.

c. 3000–2000 BC

Continued influence of Anannage/Watchers over the Sumero-Akkadian city-states. This was recorded either as contact with gods and goddesses, generally through the Sacred Marriage ceremony, or through battles with demonic bird-men, like those encountered in the Kutha tablet. Kings descended from the Anannage/Watchers are granted deification, or are looked upon as part-demon. A similar contact takes place in Media and Iran. Final fragmentation of the fallen race.

The Egyptian elder culture's apparent obsession with the measurement of great cycles of time, from the point of First Creation right down to their own epoch, would seem to have been inherited by the Watchers. If the accounts of Enoch's visits to the seven heavens are in any way based on actual fact, then it would appear that the Watchers possessed an acute understanding of astronomical time-cycles. Tentative evidence can also be found in Enochian literature for astro-mythology and precessional data.17 The Watchers would seem to have passed on this complex astronomical information to the various cultures that eventually developed across western and central Asia. This included highly symbolic myths relating directly to the precessional time-cycle and the significance of the age of Leo, as is very possibly evidenced in Persia.

During the Sassanian, or second empire, period (AD 226–651) of Persian history, there existed a very dominant form of Zoroastrianism known as Zurvanism, or fatalism. It revolved around a great god named Zurvan, a word meaning 'fate' or 'fortune', who was seen as the genius, or intelligence, of Zrvan Akarana (Pahlavi Zurvan i Akanarak), 'infinite time'.18

The principal creation myth of Zurvanism ran as follows:

In the beginning, only Zurvan existed. Then for a period of a thousand years he sacrificed barsom-twigs in the hope of achieving a son who would rule heaven and earth. At the end of this time he mixed together fire of the air and water of the earth19 to produce twins – Ormuzd (Ahura Mazda) and Ahriman (Angra Mainyu), who represented light and darkness, or good and evil. To the first to be born the great father promised dominion over the earth for 9,000 years.20

On learning of Zurvan's promise, Ahriman immediately broke free of the cosmic womb and approached his father. Yet on seeing that the child was dark and stinking, the great god realized that he was not the rightful heir. Ormuzd then was born, and on seeing that he was radiant with light, Zurvan knew that he was to be the true ruler of both heaven and earth. Yet because of his earlier pact with the first-born, he would have to grant Ahriman dominion over the earth for 9,000 years. During this time, Ormuzd was made high priest in heaven alone – and only afterwards was he able to reign supreme.

It is a simple story, but one that encodes extremely important cosmological data. The reference to 9,000 years appears to denote the period of time the Zurvanites believed that the dark forces – personified as Ahriman and his daevic offspring – ruled the world before the light of Ormuzd took control of both heaven and earth. If this archaic tradition dealt with actual and not simply metaphorical time, then when were these mythical events considered to have taken place?

The answer is simple.

The 9,000 years undoubtedly referred to the time-period immediately prior to the coming of Zoroaster, who was, of course, seen as having vanquished the rule of Angra Mainyu, his daevic race and, of course, the daeva-worshippers during his lifetime. Since we know that a figure of 258 years before the fall of the Persian empire in 330 BC was generally given as the date for the coming of Zoroaster, i.e. 588 BC, the Zurvanite time-frame implied that Ahriman had begun his dominion over the earth in 9588 BC.

This same approximate time-frame is confirmed by the chronology given in the ninth-century Bundahishn text, which states that the first millennium had begun on a date calculated by Zoroastrian scholars as 9630 BC.21 In Avestan literature dating to the Sassanian period, a figure of 9,000 years is also given as the amount of time (3 × 3,000 years) that Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu struggled for supremacy over the world.22

The coincidence of these dates to the time-scale of the global cataclysms that accompanied the end of the last Ice Age, as well as Plato's reference to 9600 BC as the date when Atlantis submerged, and, of course, the suggested time-frame of 95000–9000 BC for the establishment of the Watcher culture in Kurdistan, cannot be overlooked.

Had the Zoroastrians and Zurvanites been privy to a hidden tradition preserving the approximate foundation date of Iranian chronology -perhaps the point of genesis of the Iranian race in the Airyana Vaejah, their mythical homeland? More importantly, did the Zurvanite creation myth preserve the fact that the daevic race – in other words, the Watchers – had entered the scene around 9600 BC?

Ormuzd and his twin brother Ahriman are said to have been created out of fire of the air and water of the earth. Surely this is an abstract reference to the conflagration and flood that supposedly accompanied the cessation of the last Ice Age. If so, then it implied that the twin deities of the Zurvan myth had been born out of this age of global catastrophes, just as the Phoenix of Graeco-Egyptian legend was supposed to have risen anew from the ashes of its funeral pyre at the commencement of each new age. The necessity for two opposing forces, one ruling heaven and the other ruling earth, is perhaps yet another allegory concerning the clear split in the ranks between those Watchers, or ahuras, who remained loyal to heaven, and those, i.e. the daevas, who decided to take their chances among the developing peoples of the Near East.

The Lion-headed God

There is an even closer link between Iranian myth and the global events surrounding the age of Leo. One of the principal animal forms of Angra Mainyu is the lion, and this association is personified no better than in the mysterious lion-headed figure once venerated in the dark subterranean temples dedicated to the god Mithras. Life-sized statues of this winged deity show it with the body of a human male, a pair of keys in one hand and either the earth or the cosmic egg beneath its feet. Coiled around its torso is a snake – its head rising up over the top of the mane (or sometimes shown entering the mouth of the lion), while studded either on to its chest or carved in an arc above its head are the twelve signs of the zodiac.

Mithraism emerged into the limelight of classical history during the first century BC. According to Plutarch (50–120 AD), the pirates of Cilicia, a country in Asia Minor, conducted 'secret mysteries' to Mithra on Mount Olympus. He added that these strange rites had been 'originally instituted by them'.23 The cult's rise to prominence during this era may well have been influenced by the alliance forged between the Cilician pirates and Mithridates IV, the king of Pontus, a country in north-eastern Asia Minor, whose personal name meant 'given by Mithra' – Mithra being the deity who judged the souls after death in the Magian religion.24 Mithridates' greatest ally, however, had been his son-in-law Tigran the Great, the king of Armenia, with whom he had driven the Romans out of Cappadocia and Phrygia in 88 BC. A great number of Cilicians had been persuaded by Tigran to live in the fortress of Tigranakert, south of Lake Van, and it is extremely likely that these people introduced Mithraism into the city (see Chapter Fourteen).

The roots of Mithraism are obscure, but it is thought to have been a revitalized form of a mystery cult involving the Greek god Perseus, which had thrived in the Cilician city of Tarsus during the first century BC.25 Perseus' attributes had been combined with those of the Iranian god Mithra, and through this merging of the two deities a hybrid god named Mithras had been born.26 Both Perseus and Mithras were depicted in classical art wearing the Phrygian cap, or the cap of Hades, which had been adopted as an important symbol of the Mithraic faith. Perseus, it must be remembered, was said to have founded the Magi priesthood as guardians of the 'sacred immortal fire', and was also looked upon by the Persian race as its progenitor.27 Scholars are in no doubt that the development of Mithraism was influenced both by the Magi and Zoroastrian priesthoods, while the Kurdish scholar Mehrdad Izady is convinced that the cult owes much to the angel-worshipping religions of Kurdistan.28

Who, or what, did the cult's lion-headed god actually represent? The worshippers of Mithras have left us with very few clues in this respect, although a Mithraic scholar named Howard Jackson managed to sum up the figure's place in the cult by observing that:

The most common attributes which the [lion-headed] deity possesses suffice to identify it as what late antique texts often term a kosmokrator, an astrologically conditioned embodiment of the world-engendering and world-ruling Power generated by the endless revolution of all the wheels of the celestial dynamo.29

In other words the lion-headed deity played exactly the same role as Zurvan – it was seen as the controller of infinite time. Furthermore, another Mithraic scholar named David Ulansey made an indepth study of this deity and came to the conclusion that it was looked upon by cult worshippers as the 'personification of the force responsible for the precession of the equinoxes'.30 This leonine form was therefore believed to regulate the movement of the stars during the 25,920-year precessional cycle, immediately linking it with the Great Sphinx, which had apparently acted in a very similar capacity on the elevated plateau at Giza.

Franz Cumont, a well-known nineteenth-century scholar of Mithraism, linked the lion-headed deity of Mithraism directly with the great god Zurvan, the genius of infinite time.31 This association, however, has been seriously contested by modern-day academics, and instead the leonine figure is now thought to represent Ahriman – the evil principle of Zurvanism.32 Should this prove to be the case, then it would conform perfectly with the Zurvanite view that Ahriman had been given dominion over the earth around 9600 BC, i.e. during the precessional age of Leo. This, of course, is also the approximate time-frame in which the apparent survivors of the Egyptian elder race had established their colony in the Near East – an event which had perhaps inspired the commencement of the first millennium in Iranian chronology.

Could it possibly be that, because the inheritors of this astromythology provided by the Egyptian settlers somehow misunderstood the nature of cosmic precession, they had continued to see the lion as the kosmokrator, or regulator of time, even after the age of Leo gave way to the age of Cancer? So instead of evolving their mythological data to include the symbols of the subsequent precessional ages, these people had remained stuck in a groove that preserved the significance of the age of Leo right down until the emergence of Zoroastrianism in the first millennium BC. After this date, the leonine kosmokrator would appear to have been downgraded from its role as controller of fate and regulator of infinite time to the evil principle of the Iranian religion, its place being taken by Zurvan himself.

Could this be the true origin behind the creation myth of Zurvan tradition?

If it was, then it pointed towards a direct connection between the Egyptian elder culture's obsession with the precessional cycle during the age of Leo, and the most distant ancestors of the Iranian race. Yet the fact that knowledge of the lion-headed kosmokrator had been best preserved by the cult of Mithras hinted at the probability that they must have been privy to a hidden tradition unavailable to the Magi and Zoroastrian priesthoods of the first millennium BC. So from where might this secret knowledge have come?

The mystery cult surrounding the god Perseus, the wearer of the conical-shaped Phrygian cap, may well provide an answer. As I had already discovered, when E. S. Drower visited the Yezidi's secret cavern at Ras al-'Ain, close to the Iraqi-Syrian border, during 1940, her guide, Sitt Gulé, had pointed out strange carvings on the walls. They showed bearded personages wearing conical caps, who sat in concave frames, similar to the lotus thrones of Tibetan tradition (see Chapter Thirteen). Could it be that these wall-carvings depicted the true givers of knowledge and wisdom to the first Kurdish races? Might they show direct descendants of the original colony of Egyptian elders who had established themselves in the region sometime between c. 9500 and 9000 BC? Were they also the creators not only of the Magian and Zurvan faiths of Persia, but also of the angel-worshipping cults? Certainly, we know that the Yaresan revere the lion and the dragon (or serpent) as the keyholders and guardians of the first and fifth heavens, through which the human soul has to pass on its way to the heavenly abode.33 Had these mysterious conical–cap people gone on to provide the worshippers of the god Perseus, the traditional founder both of the Magi priesthoods and the Persian race, with intimate knowledge concerning the leonine keeper of infinite time?

On the floor of the hidden cavern shown to Mrs Drower at Ras al-'Ain were deep grooves carved into the polished stone floor. They were arranged to form 'an oblong with twelve small round depressions, placed six a side'. Mrs Drower identified the design as some kind of 'gaming board', but in my opinion the round depressions represented the twelve signs of the zodiac and, by virtue of this, the precessional cycle of 25,920 years. If so, then what type of ritual practices might the conical-cap people have conducted in this secluded cave of immense antiquity? Did they observe the movement of the precessional cycle from this place of great retreat? What other cultures did they influence? And what was their ultimate fate? Perhaps we can never know the answers.

The Theft of Fate

In Zurvanism, Ahriman differs from the evil principle in orthodox Zoroastrianism in that he is not considered to have been inherently evil. He chooses to be this way, and as an example of his wicked powers he immediately creates the peacock.34 This seemed like an absurd example of his apparent abilities. Why should he have wanted to create the peacock over and above anything else? The Yezidi revere the peacock as the symbol of Melek Taus, or Melek el Kout, the Greatest Angel, although this faith did not take its final form until the thirteenth century. The Zurvan religion had been established at least several hundred years beforehand. Since the Peacock Angel would appear to have been an abstract personification of the Watchers' influence in Kurdistan, this once again hinted at the enormous antiquity of these obscure myths and legends.

The leonine kosmokrator and its association with the Watchers of Kurdistan may also be preserved in the shape of the Simurgh, which was said to have been half lion, half eagle (or vulture). In Zoroastrian literature of the Sassanian period it was said to have sat upon the Tree of All Remedies, also known as the Tree of All Seeds, which was located in the middle of the mythical Vourukasha Sea (see Chapter Eleven). When it 'alights upon the branches of the tree it breaks off the thorns and twigs and sheds the seed therefrom. And when it soars aloft a thousand twigs shoot from the trees.'35 Imagery of this type refers quite specifically to the passage of time and the movement of the starry firmament around the cosmic axis – the thousand twigs symbolizing a thousand years, the seeds representing stars, and so on.36 Did the legends surrounding this mythical bird therefore also preserve knowledge of the precessional cycle and the age of Leo?

And if we include the Simurgh in this formula, we cannot forget that other half lion, half eagle – the Imdugud, or Anzu, of Mesopotamian myth and legend (see Chapter Sixteen). This monstrous creature was said to have stolen the Tablets of Destiny from the god Enlil (Ellil in Akkadian), which, when in its possession, gave 'him power over the Universe as controller of the fates of all',37 enough to endanger 'the stability of civilization'.38 Saying that the Imdugud had become 'controller of the fates of all', aligned it directly with the figure of Zurvan, who was also the controller of 'fate' or 'fortune'. So, in addition to its proposed connection with the Watchers, might the story of the Imdugud refer to the 'theft', or revealment, of hidden knowledge concerning the precessional time-cycle, which was seen by the Zurvanites as ruling over earthly 'destiny'?

Starry Numbers

The Imdugud's Indian counterpart, the half giant, half eagle named Garuda, was said to have stolen not the Tablets of Destiny but the moon goblet containing the Ambrosia, Amrita or nectar of the gods. Did this theft relate to astro-mythology in some way? It is difficult to say; however, it is known that the Brahmans of India possessed an age-old system of measuring extremely long periods of time spanning millions of years. This system would appear to have been based on a profound knowledge of the precessional cycle.39 Immensely long time-cycles, matching those of the Brahminic system, are also found in the writings of the Babylonian priest and scribe Berossus, c. 260 BC, as well as in a fragment of text accredited to the Greek writer Hesiod, c. 907 BC, where they are symbolized by the mythical Phoenix.40

Had all this knowledge been gained from the Watchers of Kurdistan, or had it come from Egyptian elders who may well have settled elsewhere in the world after the cataclysmic events of the eleventh and tenth millennia BC?

Allusions to the 25,920-year precessional cycle can also be detected in the heavenly architecture outlined in a Manichaean gospel of the third century entitled 'The Myth of the Soul'. Chapter Eleven, for example, reads as follows:

Now for every sky he made twelve Gates with their Porches high and wide, every one of the Gates opposite its pair, and over everyone of the Porches wrestlers in front of it. Then in those Porches in every one of its Gates he made six Lintels, and in everyone of the Lintels thirty Corners, and twelve Stones in every Corner. Then he erected the Lintels and Corners and Stones with their tops in the height of the heavens: and he connected the air at the bottom of the earths with the skies.41

Multiply the 12 Gates with the six Lintels to each Porch and you get 72 – the number of years it takes for the earth to move 1° of a precessional cycle. Multiply this number with the 30 Corners of each Lintel and you get 2,160 – the number of years in one complete precessional age. Multiply this figure with the 12 Stones in every Corner and you arrive at 25,920 – the number of years in one complete precessional cycle.

Since the passage in question concerns the ethereal architecture of the heavens, I find it difficult to see this numerology in terms of pure coincidence, suggesting therefore that the Manichaeans were carriers of precessional information that was of extreme age even in their own day.

In addition to these examples, clear knowledge of the precessional cycle can be detected within the Yezidi belief in the 72 Adams who each lived 10,000 years, between which were further periods of 10,000 years when no one had lived in the world. Simplistic as this time-cycle may seem, the 72 Adams refer to the 72 years it takes for the starry firmament to move 1° of a precessional cycle, while 1,440,000 – the total number of years alluded to by adding together these amounts – is another important figure in the precessional canon of numbers.42

How had the Yezidis come into possession of this complex system? Had it been from the Watchers? Or had this knowledge come from the conical-cap wearing people depicted on the walls of the hidden cavern at Ras al-'Ain in the Kurdish foothills?

Universal Language

The presence of age-old precessional data is not, however, confined to the mythologies and religious traditions of western and central Asia. It has also been detected in myths and legends all around the world. Giorgio de Santillana, a professor of the History of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, made an in-depth study of these legends and traditions and published the results in an important work entitled Hamlet's Mill, co-authored with Hertha von Dechend, a professor of the history of science at Frankfurt University. They put this universal knowledge of precession down to 'some almost unbelievable ancestor civilization' that 'first dared to understand the world as created according to number, measure and weight'.43

The Egyptian elders were almost certainly that 'unbelievable ancestor civilization', who had paved the way for the genesis of our own world civilization in the mountains of Kurdistan sometime around 5000 BC. As I also now realized, they were very probably the true source behind the traditions concerning the angels and Watchers of the Book of Enoch, as well as the gods, goddesses and demons of ancient Mesopotamia; the Shining Ones of Iranian tradition; the giants and Titans of Greek and Armenian mythology; and the fire djinn and Cabiri of Asia Minor. These were powerful realizations, yet they left me feeling just a little uneasy. Why had these people been so insistent on leaving us timeless legacies in the form of the geo-mythic data encoded into the Giza plateau and the universal language of astro-mythology preserved by so many cultures relevant to this debate? What were they trying to tell us? And just what do these legacies mean to the world as it blindly embraces the new millennium?