A Glowing Heart

I’ve seen men die here, up on the cloud-cliffs. I’ve seen them come with their bags and binoculars, their books and charts, chatting away like it’s all a bit of leisure, like it’s all a show. I used to come up here with Dad when he led the tours, showing people the best spots to see the birds. He never said so, but I knew he hated it, hated taking their money and leading them along the ridges, from clouded peak to peak. You could see it in his face, a torn-up kind of sadness, as if he were selling secrets.

I’ve seen men jump from one peak to another as if it’s a joke, like it’s not a sheer drop down to the bottom, all three, four, five thousand feet. I’ve seen the shock on their faces when they lose their footing and realize what they’ve done, when they realize it’s too late.

“People think they’re bigger than this place, you see.” That’s what Dad used to say. “They think it’s there for their own sake, but it’s not. It’s bigger than that, bigger than us.”

I never really knew what he meant by that, but I think I know now. Now, while I lie watching the cliffs and the sky, waiting for a light-hawk to emerge, waiting to shoot it out the air and steal its heart. Waiting to die a little bit myself, too.

I don’t want to kill the bird. I can think of very few things I’d want to do less. But I don’t want Mam to die either.

After five hours of hunkering in the same place, chewing on grass, I still haven’t seen it. Part of me is glad, because if I see the hawk, it means I’ll have to do something awful. But part of me thinks of Mam at home, lying in her bed, the sweat on her face and the confusion in her eyes, as if she can’t recognize me anymore through the pain. And I think of my brother, Nevan, what he’ll say if I come home empty-handed again.

We’ll get decent money for the feathers, for rich people in the city to use as ornaments. But the heart is the real prize. Even after the bird is dead, it keeps going, pulsing light like a miniature sun. Nevan knows someone who’ll pay us well for it, enough to buy the medicine we need for Mam. Enough to save her.

When I’ve finished all my grass, sucked the flavor from it and spat it out, and after the day has begun to dissolve away into evening, a light-hawk appears. With the sun drooping below the horizon, the bird is the brightest thing in the sky, and when the arc of its flight crosses in front of my binoculars, I have to close my eyes.

The light-hawk hangs in the air, watching, trying to find muckle jays out looking for mates, or young fleet-tits yelping in their nests, waiting for their mam and dad to come back with food. I lie there watching it, forgetting for a few moments the reason I’m here.

Each of her feathers is like a leaf of glass, her beak and talons like precious metals, molded and refined through fire. And she glows from within.

The light-hawk spots something, and moves. She plummets through the air, almost vertically, and when she hairpins back skywards, perfectly parallel with the wall of one of the cloud-cliffs, she has a young muckle jay in her beak, already dead. When she’s back up to height, she tosses the little bird and catches it again, as if she’s celebrating. Spots of blood careen through the air, glistening, reflecting the hawk’s light back at it.

I draw the arrow already nocked in my bow. I wait until she’s in range, and above land, and I fire. It’s a bad shot, lacking conviction. The light-hawk doesn’t even flinch, but before I can nock another arrow and steady myself, she’s veered again, arcing through the sky, and then she’s gone.

When I get back home, Nevan is waiting for me.

“Well?” he says, but he’s already seen my bag, empty.

“What happened?” he says, but I don’t know how to respond.

I try to walk past him but he grabs hold of my shoulder. “What the hell’s wrong with you?”

I struggle out of his grasp and run inside. I want to break something, smash something, but then I remember Mam. I climb up the stairs and go through into her room. She’s asleep on the bed with a blanket pulled up to her chest, and she’s wearing one of Dad’s old shirts. I place my hand on her forehead, feel the heat. It’s been a week, now, and it’s only getting worse.

Downstairs, Nevan is sitting in the kitchen, sipping a cup of herbs. He stares at me.

“I didn’t see one,” I say. “Not one all day.”

It should be him out there, but he hurt his leg half a year ago, and he’s been limping ever since. It’s hard enough for him getting to work and back every day, and he’s in no state to lie out on the cloud-cliffs waiting for a bird to appear, especially when there’s so few of them around. So that means it’s down to me.

“You’ll go out again tomorrow?” he says, but it’s more of a statement than a question. “She’s getting worse,” he says, not looking at me, and then his voice gets quieter. “We’re running out of time.”

“Aye,” I say. “Same again tomorrow.”

When I was younger, I wanted to be the greatest falconer in the world. I told Dad I’d catch a light-hawk and train it, and we’d be a team. Dad stared at me like I was daft. “You might as well try to train a hurricane,” he said.

Dad never really talked much about the beauty of the birds, or the poetry in the way they moved through sky, incandescent, but he didn’t need to. He did talk about respect, though, about knowing our place in relation to them. “They’ve been here longer than we have,” he would say.

I knew that must be a long time, because our family has lived in these parts for decades now, rippling back through the generations. We used to live off the land, foraging for plants up on the cloud-cliffs, but then the prices fell and we couldn’t make a living from it. That was when Dad started doing the tours, taking groups out onto the cliffs, showing them how to cross the peaks, the clouds swirling about. People came from miles around to see the birds, but what they wanted to see most was a light-hawk. You don’t get them everywhere, you see. They live alone, never with a mate, hardly ever producing young. Some people think they’re immortal.

When Dad died, Nevan took over the tours, but he never loved the place the way Dad did, and eventually he gave up. I wanted to take over myself, but Mam said I was too young, so recently I’ve only gone up to the cloud-cliffs for my own sake, to pick dewberries and black root, to see if I can catch a glimpse of a hawk, a surge of light. Until now, that is. Now, I bring death.

In the morning, I go out again, like I said I would. I find the same spot as yesterday and settle into position. Down below me a ledge juts out of the cliff side. There’s a nest there, with three little fleet-tit chicks screaming for food, their blue plumes shaking. I watch them for a while, hoping the light-hawk might pass by while I’m distracted, hoping I won’t have a chance to do what I’m here for.

Around midday, the sun looks bigger than usual, brighter. It takes a few seconds for me to realize that it’s the light-hawk, gliding in my direction.

I tell myself to move, but I can’t. All I can do is watch her go, until she disappears out of sight.

I run home. Nevan is still at work, so he’s not there to greet me, not there to tell me how I’ve failed, how it’s my fault if we don’t get the medicine in time.

But maybe there’s another way.

I comb the house, searching for anything of value. I find some old books in decent condition, some silver cutlery, Dad’s old pocket watch he gave me before he died. He’d hate the idea of me selling it, but if he knew what the alternative was … I feel sick just thinking about it. I gather up this scattered collection, a box of paltry offerings, and I wait. When Nevan comes home, we’ll take it all into town; we’ll sell it, and we’ll buy the medicine for Mam.

Nevan slumps through the door after dark, his eyes weary. I’m waiting for him, but he takes one glance at my collection and smacks me round the head. “This is what you’ve been doing all day?” he cries, and I can’t look at him. “Did you even go to the cloud-cliffs?” he says.

“I did, I tried, but I couldn’t do it.”

He grabs my collar and pushes me up against the wall. I struggle against him but he’s too strong. “You need to try harder, don’t you?” He screams and knocks a chair over, and then it’s like he’s a pair of bellows and all the anger’s been pushed out of him. He sits there with his head in his hands, and then he goes up to see Mam. I don’t follow.

In the middle of the night, I’m woken by shouting, like someone’s having a fight. I run into Mam’s bedroom to find Nevan there, grappling with Mam while she convulses. “What’s happening?” I shout, but Nevan ignores me, his hands fixed on her shoulders. In a few seconds, she goes from a whirling storm to a gentle breeze, and then she’s still. My brother stares at me. He doesn’t say anything.

I don’t sleep the rest of the night. I wait until it’s just starting to get light, and I set out for the cloud-cliffs.

This time, it doesn’t take long to see the bird. It flies in a great circle, cuts rings in the sky, hits a pocket of warm air and soars upwards before gliding back down, always watching.

I think of the first time I saw a light-hawk, with Dad. We’d been watching for hours, me complaining most of the time. How could a bird be worth so much waiting, sitting around for a whole day? Then I saw it. It was like a shooting star, like a scorching spark from a bonfire, like the sun itself, breaking from behind the clouds. Dad fell silent, and so did I. I felt giddy on the way home, and closer to Dad than ever before, as if he’d told me something no one else knew, me and me alone.

And then I think of Mam, lying there in bed, the sickness taking hold of her.

The arrow in my hand has feathers at the end of the shaft. They’re nothing like the feathers on the light-hawk, but they might be enough. I nock the arrow in my bow and pull it back, my arm shaking from the tension, from the weight of what I’m about to do.

The hawk hovers, almost stationary, lifted by an updraft. It’s almost like she knows what’s happening, can feel the yawning pit in my stomach and wants to make it easy for me.

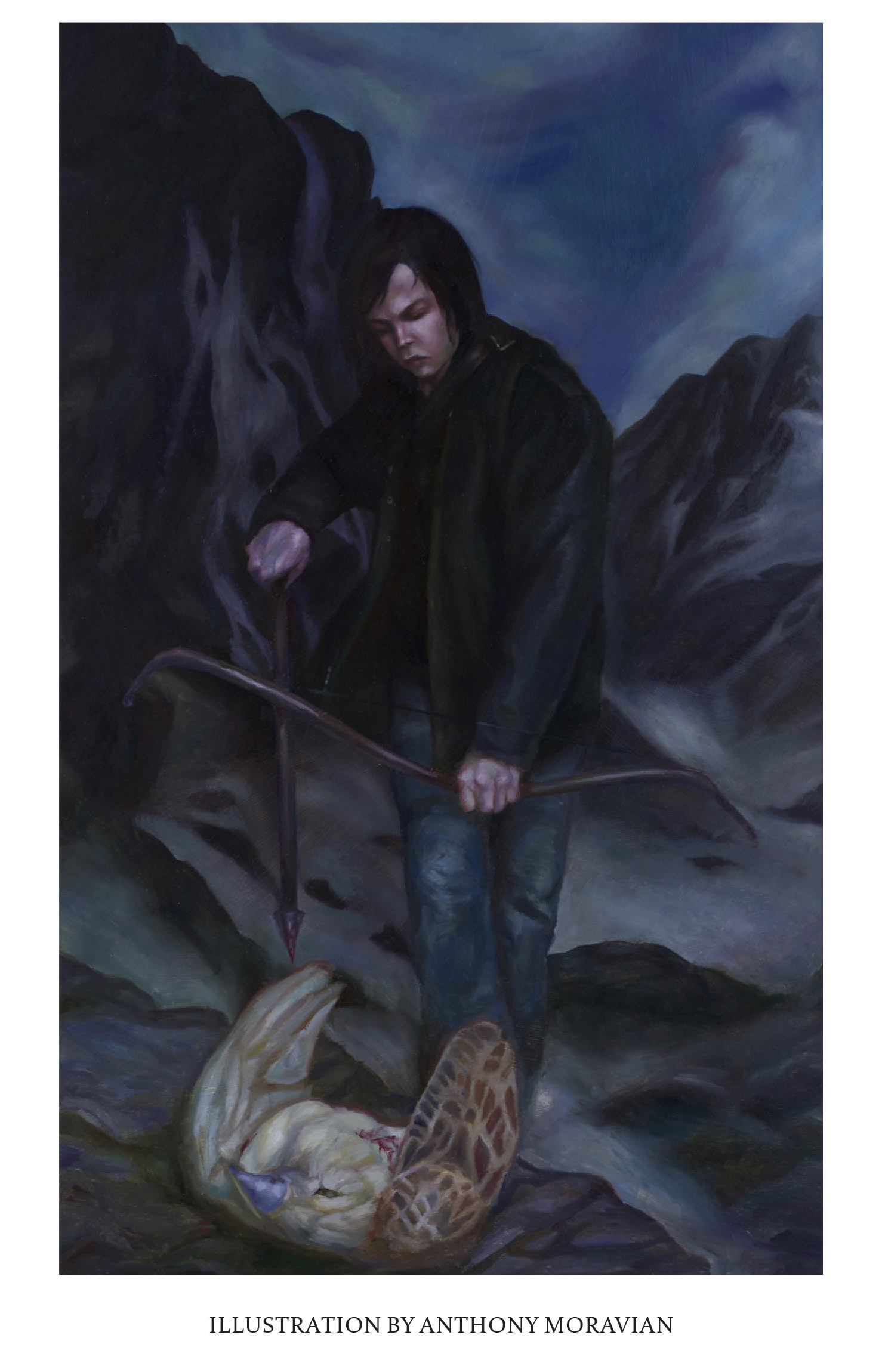

I loose the arrow. It arcs through the air with violence, inelegance, and it pierces the bird.

I drag myself over to where she lands, my legs swaying as I cross the gap between peaks, the clouds swirling beneath.

The bird is warm in my hands. She’s even more beautiful up close than she was in the air. I study the patterns of the feathers, the way they refract the light, bending and shaping it like crystals, or running water. The bird still glows from within, a beating furnace. Only its eyes are dark.

“I’m sorry,” I say, over and over until my throat is dry.

Nevan takes the bird from me, hardly saying a word. He goes into the shed to butcher it, to slide the feathers from their crystal casing, to remove the glowing heart.

I can’t bear to watch. I lie in bed, wishing none of this had happened. I can’t even bring myself to check in on Mam.

Nevan leaves for the city early in the morning. I sit in the bedroom with Mam, watching her. I place damp towels on her forehead, and I change her bedpan, and I think about how the sky around the cloud-cliffs is dimmer now, how there’s less light in the world thanks to me. I think about what Dad would say. Every now and again, Mam’s eyes open and she gazes at me and says my name.

The door opens downstairs. Nevan has a big smile on his face, and he’s holding a bottle of syrupy-looking liquid in his hands. “I got it,” he says, roaring triumphantly. “I got it.”

I run toward him but I stop halfway. “What’s that you’re wearing?” I say.

He puts the bottle on the table and takes off his coat. It’s one I’ve never seen before. “There was some money left over,” he says. “Look, it’s like pure gossamer. Warm as anything.” He holds it out to me but my arms are down by my side, my hands balled into fists.

Nevan opens his bag and takes out another coat, folded in two. “I got one for you, too, and for Mam. They’ll be great in the winter.”

Before he’s even finished speaking, I’m charging toward him, my arms flailing all around. I land a few blows on his chest but he’s bigger than me, stronger too, and he holds me off.

“What the hell’s wrong with you?” he says.

I open my mouth but I can’t say anything, and I can feel my eyes welling up. I grab the coat and run out the front door.

I run and run until I’m at the cloud-cliffs. It’s dark now, the sun below the horizon. It’s dangerous traversing the peaks in the daytime; without the light of the sun it would be suicide. I stand at the edge, feeling bile rise in my stomach, and I throw the coat into the air. It flattens out and floats down, spiraling until it hits the clouds, and then it’s gone.

The medicine works. It takes time, but even after a day, the change is undeniable. Mam smiles at me and asks what day it is, says she can’t remember much. I don’t tell her what’s happened, what I’ve done. Maybe I never will.

When I’m not with Mam, I’m out at the cliffs. I lie in place, waiting, hoping I might see another light-hawk. Nothing.

On the third day, when the sun is almost set, I notice something glowing on one of the outer peaks. I know I should come back tomorrow when it’s light, when I can see where I’m placing my feet, but I go anyway. Maybe there’s a part of me that won’t mind if I lose my footing and fall.

I move from peak to peak, the clouds swirling around and below me, my heart racing as the stone and dry moss scrunch below my feet. The air is thin and my breath is short but I can’t stop. A couple of times I feel my balance going but I swing my arms around and recover. It’s only luck or instinct that stops me from falling.

At the outer peak, I find the source of the light. Hidden away in a rocky crag is a small nest, made from twigs and pieces of moss. There’s an egg cradled in the center, glowing from within. I cup it in my hands.