As Silver Nightly held the door open for Tuesday and Baxterr, a swirling breeze from outside blew the old man’s big white hat clean off his head, and his white hair flew up in a crazy halo around his face. Baxterr took off across the balcony as if somebody had just thrown a Frisbee, and he managed to catch hold of the brim neatly in his teeth before the hat could whirl away and be lost forever in the mist. He trotted back to Silver, tail wagging.

“Why, thank you mightily, my friend,” Silver said. “I’m indebted to you. A man without his hat is like a snake without a slither.”

Juggling his bowl of chili beans, Silver wedged his hat down tight over his crinkled forehead. The breeze gusted again, this time from the opposite direction, and Tuesday felt a shiver run down the length of her spine when she saw the ruins of the once-magnificent balcony. Whole sections of the marble railings were missing, while the parts that were still standing were damaged and crumbling, as if the balcony had been chewed by giant teeth. Tuesday remembered how several sets of binoculars had been spaced out along the balcony railing. But most of them were gone, torn away with the railing itself, and the few that remained were smashed into unworkable twists of metal and glass.

“It’s like there’s been a…,” began Tuesday.

“Global emergency,” Silver finished. “And you’re right. That’s pretty much what it is. Which is why you ought to get those chili beans on board.”

They sat on a marble bench that was mostly intact. Tuesday set Baxterr’s bowl on the ground at her feet. She tore the bread she’d found into pieces and shared it between them. Baxterr sniffed the food and licked at it hesitantly, but the next time Tuesday checked on him, his bowl was quite clean and the bread gone.

“Nothing like chili beans for a cold night on the prairie,” said Silver Nightly when his own meal was mostly consumed. “Or sunrise on the great plains. You can have it for breakfast, lunch, or dinner, and it only gets better as the days go by. A pot of chili beans can last you a week, and you just keep adding to it. Throw in a bit of sausage, another can of beans, and another of tomatoes. I myself am rather partial to having it with a rasher of bacon and a fried egg on top, but as you can see, we’re not blessed with too many luxuries today.”

He winked at Tuesday.

“You might not remember me,” he said, “but some time ago, I saw you right here on this very balcony. And I won’t ever forget what you did. How you disregarded the Librarian’s instructions and took a path not many writers would have had the courage to take.”

Tuesday’s mind flashed back to the time she’d come looking for her mother and the Librarian had tried to stop her from entering the world of Vivienne Small.

“It was you!” she said. “You distracted her, and I got away!”

“That’s right.” Silver Nightly chuckled. “I call what you did uncommon valor. It’s a rare quality to leap into the complete unknown, and you did it for someone you love. Well, what we’ve got ourselves here is a bit different, and some of it you’re beginning to understand.”

“I know the worlds are colliding,” said Tuesday. “That’s why writers are getting hurt.”

“Is that so?” Silver mused. “Well, then, let me tell you what I know. I write Westerns. In fact, I’ve written one hundred and four Westerns and am right in the middle of my one hundred and fifth. I like horse country. I like canyons. I like wide blue skies and red rocks. I like sagebrush and eagles and smoke on the horizon. So all of that is exactly what I find when I step out there.” He waved a hand toward the mist. “Back in the dining room, that real lovely woman with the yellow head scarf, did you see her? Well, she writes about a world that exists a thousand years from now, when the rivers have dried up and the cities have been destroyed by ice. And that poor fellow in Madame Librarian’s study? He writes from a place that’s a lot like the city of London more than a hundred years ago. When each of them steps off this balcony, that’s where they go—into a world of their own choosing, and their own making.

“What I’ve thought is that there must be someone keeping an eye on how all this fits together and holding everything steady. We never run across one another. My story never runs into anyone else’s. The only time us writers ever see one another is here, in the Library. Out there … well, it’s all our own, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” said Tuesday, remembering vividly how very alone she had felt when she discovered this on her first visit. “So who is this someone who keeps the worlds apart?”

“I don’t rightly know, young lady. For a long time, I figured it was Madame Librarian, but clearly that isn’t so.”

Tuesday nodded, thinking she was willing to bet that the person’s name started with G.

“I’ve come to think,” Silver said, “that it’s a sort of partnership—between the worlds and the stories. Makes sense, hmm? Madame Librarian is in charge of the books and the writers. But I’d bet a whole herd of cattle that someone else takes care of the rest.”

“How could they possibly manage every world that every writer creates?” Tuesday asked.

“Well, they’d need help, wouldn’t they? They’d need some sort of magical powers, or a machine. Something that could let them see into all the worlds, keep everything sorted and separate. Maybe they even have a way to move between worlds.”

“Move between worlds?” Tuesday repeated. The idea was fascinating.

“Yes. There aren’t many creatures that can do it,” said Silver Nightly. “They have to have a little magic. Dragons, for instance. Though from my understanding, they’re hard to train.”

“You mean this someone might have a dragon? Maybe they are a dragon.”

“Possibly. But I doubt it. I think they’re like the Librarian. I mean human, of a sort—a very long-lived sort. My sense is that Madame Librarian has been here a good many years.”

Tuesday ate the last of the chili beans and wiped out her bowl with the bread, all the time thinking as she chewed. She wanted to share the contents of the note with Silver Nightly but thought that, as it was private and addressed to the Librarian, she’d better not. Still, she wondered aloud, “What’s gone wrong? Why isn’t this person doing their job?”

“Perhaps they can’t,” Silver said. “Perhaps they’re dead. Hard to do your job when you’re dead. Or feeling poorly. Whichever way, you only have to look about us to see that something that was working fine is pretty much broke. Worlds have been crashing into each other, and into this here balcony too. I don’t much like to think about what’s going to happen if things get any worse.”

“Where do you think this someone lives?” Tuesday asked.

“Ah, well, that’s the great mystery. I have a feeling that our Madame Librarian is going to ask something mighty big of you, my girl.”

“What?”

“Maybe she intends for you to go find this somebody.”

“Why me? Why not you?”

Silver Nightly said gently, “Oh, I think this particular situation calls for a young mind of particular imaginative abilities. Someone who can think up just about anything. The thing about getting older is that your mind isn’t as nimble as it once was. I love being here more than anything in the world. Since my wife died, why, I spend every moment here I can. But I tend to solve things the same way, time after time. And I don’t have a dog like yours.”

“Like mine?”

Although they were quite alone on the balcony, Silver dropped his voice. “I’ve been wondering about your dog ever since I saw him here the first time. In all my years—and one hundred and four and a half novels—I have never seen a writer able to bring a pet here. Until recently, I have always had a dog, but no matter how much they might have liked to, none of my dogs ever managed to come here with me. I have friends with dogs who never leave their sides. Lay under their desks as they write, sleep on their beds at night, and not one of them has ever accompanied them here. A lady crime writer I know has a parrot that’s two hundred and seven and has belonged to four generations of writers. Even so, it has never, not once, come here with her. So what I’ve been thinking is, maybe your dog isn’t like other dogs.”

Tuesday blushed.

“Pretty rare in my experience to find a dog that can travel between worlds, yes?”

“Maybe,” said Tuesday.

“I think that’s why Madame Librarian might be considering sending you on this mission. You keep that in mind,” said Silver Nightly. “And keep your dog close by you.”

Tuesday nodded. She felt Baxterr lean briefly against her leg and sensed that he had heard and understood everything Silver Nightly had said.

Tuesday felt very grateful to Silver, but before she could say thank you, she saw something phenomenally large emerging from the mist beyond the damaged balcony. Without quite meaning to, she screamed.

The thing coming toward them was a huge globe, like a cross between a planet and the largest soap bubble you’ve ever seen. Its surface was transparent, glistening with a rainbow-colored sheen, but inside she glimpsed yellow fields and a farm or two and threatening storm clouds. Baxterr barked at it furiously.

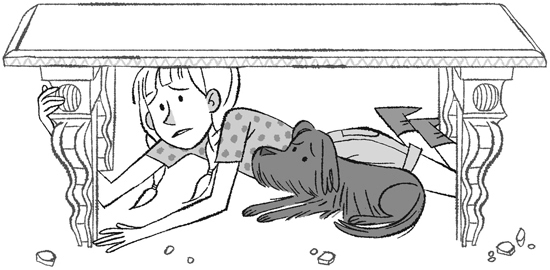

“Under here! Quick!” Silver cried, and he pushed both Tuesday and Baxterr underneath the marble bench upon which they had been sitting. Then he wedged himself in the front to protect them. “Brace!”

Then came the impact, and it felt the way Tuesday imagined an earthquake would feel. The Library shuddered and rocked. Screams and groans came from the writers inside the dining room. Saucepans hit the floor. Plates and bowls smashed. And from deeper within the Library, Tuesday heard the sound of books falling from great heights, off their shelves and onto the floor.

“Going to be a mighty effort to get them back into alphabetical order,” Silver whispered to Tuesday in the sudden, eerie silence that followed.

Silver stood up, brushing dust off his arms and shoulders, and Tuesday watched as chunks of the balcony fell off into space.

“Silver! Silver!” called the Librarian, hurrying through the french doors and onto the balcony. “You’re needed inside. Poor Cordwell has become utterly hysterical. Will you see to him for me? Thank you, thank you. There’s a good fellow. Now, I must find Tuesday and that dog of hers. I need them right away. Right away!”

“They’re just under here, Madame L,” Silver said. To Tuesday and Baxterr, still under the bench, he said, “I have to be going. You two take care, and remember all I’ve said.”

“We will,” said Tuesday. “Good-bye, Silver.”

“How’s about we don’t say ‘good-bye’? Only ‘so long,’” he said with a warm twinkle in his eyes. And then he was gone.

Tuesday scrambled out from under the bench. The Librarian was more disheveled than ever.

“Oh, thank the letters of the alphabet! There you are, Tuesday McGillycuddy,” said the Librarian. “And your dog?”

“Ruff,” said Baxterr, appearing from behind Tuesday’s legs.

“Good. Yes, very good.”

The Librarian inhaled deeply. She held a small scroll of paper sealed with a blob of purple wax and imprinted with the image of a lion.

“I do not like to commission stories,” she said, tapping the scroll of paper on the palm of her hand. “I have always prided myself on letting writers have their heads entirely, but in this case, Tuesday, I have no choice. No choice at all. Will you accept my commission?”

“I … I don’t know. I’m not sure. What—”

The Librarian cleared her throat, and it came out sounding like a slightly menacing growl.

“A few moments ago, you said you would be willing to do anything—anything!—in the service of this place. Did you not?”

“Yes, yes, I did say that,” Tuesday said in a small voice.

“Thank you. Now, what I need you to do is to write one of the most important stories of all time. Do you understand me, Tuesday McGillycuddy?”

Tuesday’s heart was beating faster than she had ever known it to go. Her parents would be wild with worry as it was, and it seemed she was not going home anytime soon.

“The story I need from you is a story about a man,” the Librarian continued, “who dwells in that space between worlds. He is a very, very old man. He is not known to many, but those who do know him call him the Gardener.”

“He’s G, from the note?” Tuesday said. “It was his dog?”

“Quite so,” said the Librarian briskly.

“He keeps the worlds apart?” Tuesday asked.

“Up to this point, he has,” the Librarian said, “and a great deal more. However, as you can see, he needs some assistance. I do not especially like to give clues. I like to let writers work things out for themselves, but time is of the essence. Are you listening? Tuesday? Baxterr?”

“Yes, I’m listening,” said Tuesday.

“Ruff,” agreed Baxterr, his tail wagging.

“In the world of Vivienne Small, you will find a way to him in the City of Clocks,” said the Librarian.

“The Gardener?”

“Yes. Mind, you will have to keep your wits about you,” said the Librarian, hurrying on with her instructions. “There will be a door.”

“His door?”

“You will know it when you see it.”

“Will I need a key?” Tuesday asked.

The Librarian paused. “Baxterr will be … essential. When you find the Gardener, you must give him this message.”

She placed the scroll of paper into Tuesday’s hand, which she held on to for a moment. A troubled expression passed over her face, but she shook it away.

“It will, of course, be up to you to tell the Gardener about his dog. Naturally, it will devastate him. And then, what you must do is help him,” the Librarian said.

“Help him? How?” Tuesday asked, wondering what on earth she could do to help someone who was either very old or very sick keep all the story worlds from crashing into one another.

The Librarian glared at her, her eyes a deep and serious shade of purple.

“How much assistance do you require with this story of yours? Hmm? For goodness’ sake, girl, use your imagination! Imagine! Is that not what we do here?”

“I’m not a real … I mean, I’m only a beginner. I mean, what about the writers inside? There must be hundreds of them. Why not one of them? Why me?”

“Because this is the story that came to get you, Tuesday McGillycuddy. The dog traveled with its message through the world of Vivienne Small, and when the dog fell, a story was born, and that story came to find you, and no one but you. And that means that this story is yours to tell,” the Librarian said.

Baxterr wagged his tail and barked as though in complete agreement with the Librarian.

“Hold on. You’ve forgotten Vivienne Small!” Tuesday protested. “We’ve left her out front by the lions. Vivienne has to come too.”

“Yes, yes, I’m sure she has a part to play,” the Librarian said. “She’s exactly where you left her. Follow the balcony around to the front path. Now, go, Tuesday. And tell him … yes, tell him…” Here the Librarian hesitated for a long moment, and then she said, “Oh, never mind. Give him my note. When he reads it, he will know what to do.”

The Librarian’s face was both fierce and gentle at once.

“Make your story strong, make your story true,” she said. “And please, please, Tuesday dear, give careful thought to how it ends. Or yours could be the very last story … ever.”