A very long way from the Peppermint Forest, Denis McGillycuddy was in his tartan dressing gown making pancakes. It was Sunday morning, and the McGillycuddy house, the tallest and narrowest house on Brown Street, was in the special variety of chaos that comes only at the end of the summer holidays. The fridge was papered with sticky notes on which had been scribbled potential names for characters (Lydia Bottle, Maple Hartigan, Volker Fink). On the windowsill was a procession of shells and fossilized sea stars (banded trochus, purple linckia, marbled fromia) and other mysterious maritime objects that Denis had shaken out of pockets and bags while unpacking from the family’s three-week escape to a faraway island with palm trees and warm, aqua-blue water.

Since the McGillycuddys’ return to Brown Street, meals had been taken at erratic hours and in all parts of the house, so that cups and plates and forks and spoons had migrated to bookshelves, chairs, mantelpieces, and even the bathtub. Abandoned board games and half-finished crossword puzzles cluttered every surface in the kitchen, while striped beach towels and gritty bathing suits languished in the laundry. No matter how many times Denis swept, he couldn’t get rid of the crunch of fine-grained tropical sand on the floor.

It was a quarter to eleven, and although Denis could hear no movement from the upper floors of the house, he was not surprised. Last night on his way to bed, when he had looked in on his daughter, Tuesday, he had found her still sitting up at her desk, tapping away on the keys of her baby-blue typewriter. It had been nearly midnight.

* * *

Tuesday was working on a story, the same one that she had been working on for every spare minute of her holidays. During the weeks they had spent on the remote island, Tuesday had barely been separated from her typewriter. She had written while sitting on the beach, while drifting in a kayak, and while lying under a mosquito net. She had written while sipping coconut milk and while hermit crabs crawled over her toes. And then, after returning to Brown Street, Tuesday had written at her desk in her bedroom, and under a tree in City Park, in the local library, and at the kitchen table before and after (but never during) breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Very late nights had become something of a habit.

But while Tuesday was sleeping in, the other writer in the house had risen early, roused by the sound of a summer rainstorm on the roof. Since before dawn, Serendipity had been in her writing room on the top floor of the house, sometimes rapping urgently on the keys of her typewriter and other times simply sitting with a blanket about her, her elbows on her desk, staring out through an open window at the morning clouds. Serendipity had once told Denis that it was hard to say which was more important, making words on a page or staring out the window, having ideas. Both were essential for a writer.

Downstairs in the kitchen, Denis set his pancake mixture aside to rest, checked the clock again, and resolved to give Tuesday and Serendipity until eleven o’clock before disturbing them for breakfast. To fill the time, he folded a load of clean washing, rustled up Tuesday’s school uniform from the bottom of the ironing basket in readiness for Monday morning, and then went to fetch the Sunday paper from where it had landed on the front steps.

He shook the newspaper open quite casually, but what he read on the front page made him sit down on the top step, which was wet from the rain, stand up again, turn around, and turn around again. Then Denis did something very unusual, something quite unprecedented, in fact. He burst back through the front door and ran noisily up four flights of stairs and barreled into Serendipity’s writing room. She sat at her desk wearing the vague expression she always wore when she was daydreaming.

“Thank goodness!” Denis said, but his relief was only fleeting.

He swooped past Serendipity, his dressing gown billowing out behind him, and pulled the window shut, banging the clasp in place rather more forcefully than was necessary. And then, as if to be doubly cautious, he hastily drew the curtains, dimming the room almost entirely.

“You have to stop immediately!” Denis said. “No writing! No thinking! No imagining! You have to stop it right now.”

Serendipity blinked, flicked on her desk lamp, and stared at Denis, who, breathing hard from having run up the stairs so quickly, was waving a newspaper around. She appeared to observe his unusual behavior as though from a long way off until at last her eyes focused and she took in the panicked expression on Denis’s face.

“Darling, what on earth is going on?” Serendipity asked.

“Here, here!” he said, thrusting the newspaper at her.

The headline read EXCLUSIVE! SEVEN WRITERS ABDUCTED.

“Abducted?” Serendipity asked.

“So the story goes. For now, at least.”

Serendipity read the article aloud: “Crime might be her career, but J. D. Jones, one of the world’s most admired writers, never imagined she would be part of a real-life global mystery. Jones was found wandering in the streets of Abu Dhabi last night. She is reported to have no memory of how she came to be there or how she sustained a broken arm. Jones is not alone. In the past five days, six other famous writers have been abducted from their homes, only to reappear in distant locations with no memory of how they got there or of their kidnappers. There have been no demands for ransom. Police are seeking any information that might indicate a motive for these increasingly bizarre disappearances.”

Serendipity stared in alarm at the photographs of the writers who had turned up in all manner of places. One from France had turned up in Alaska. Another from Sydney had been found in Cape Town. Two British writers had been discovered in Kansas, and a Chinese writer had been rescued from high in the mountains of Argentina. All of them claimed they had gone to bed, and when they had woken up, they found themselves half a world away from home, without money or a passport, and with no way of contacting their loved ones. Some had broken bones; others had suffered burns, cuts, and bruises.

All the color drained out of Serendipity’s face.

“Denis,” she said, “where is Tuesday?”

“Asleep, I imagine. She was still writing at midnight, so I thought I’d let her sleep as long—”

“Midnight? But where is she now? Denis!” Serendipity grasped her husband by his elbows.

He said, “You don’t think … surely not? These are published writers, famous writers. Tuesday’s just—”

“Denis, was she writing? When you checked on her? What was she doing?”

Before Denis could reply, Serendipity had flown past him, out the door, and down the stairs to Tuesday’s room.

* * *

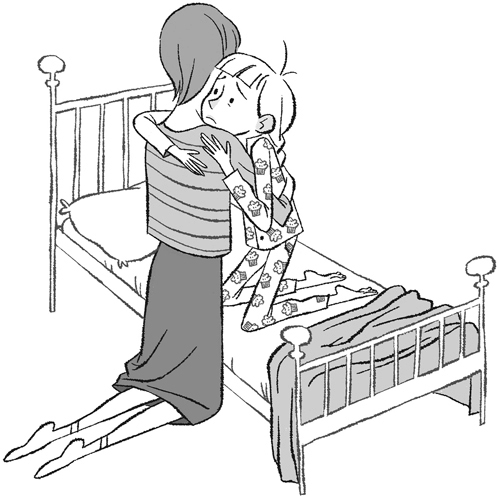

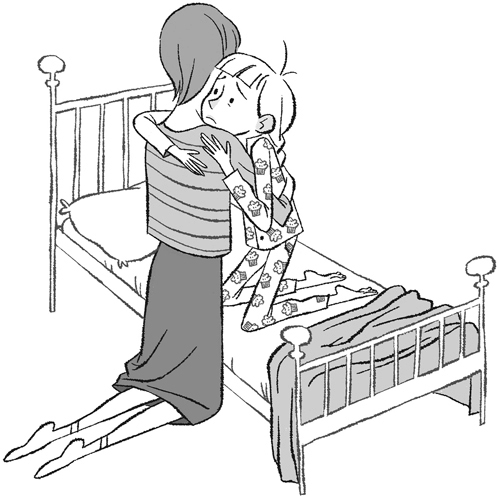

Tuesday woke to shouts of “Tuesday! Tuesday!” and the sound of rapid footsteps on the stairs outside her room. She lurched upright. Her strawberry blond hair looked as if it had fought with a cat in the night.

“Sweetheart,” said Serendipity in relief, sweeping Tuesday into an almost violent hug.

“What? What? I’m right here,” Tuesday said.

“I have never been so pleased to see you. Well, perhaps I have. When you were first born. And then, a little while ago, when you got back from being there. Well, I was very pleased then too, but I still think that—”

“Mom, you’re blathering. Could you stop squashing me?”

“Thank goodness you’re here!” said Serendipity, letting go at last.

“Where else would I be?”

“Who knows, darling? Belize? Afghanistan? Japan?” said Serendipity, handing the newspaper to Tuesday.

Tuesday pushed herself upright and rubbed her eyes.

“Here, let me,” said Denis impatiently, and he plucked the newspaper out of her hands and read aloud the headline and the text below. He turned the newspaper to Tuesday and showed her the photographs.

A feeling of dread washed over Tuesday. This was not, she realized, only news about other people. This was news about people like her mother.

“What’s happening?” Tuesday asked. “Mom?”

“I don’t know. I really don’t know.”

“They weren’t abducted, were they?”

“Not a bit, darling,” Serendipity said. “But the fact that it’s a lie doesn’t make it any less worrying.”

What Serendipity knew, Tuesday knew too, as did Denis, of course. The writers who had been found thousands of miles from home—some with broken bones, all with injuries—had not been kidnapped. Nor had they been asleep when they’d vanished, as they claimed. They had all been quite awake.

“Something’s wrong there. Isn’t it, Mom?”

There. It was the only word Tuesday could bring herself to use for the world of story that existed on the other end of a silvery thread of imagination—a magical place that was the collective secret of every writer who ever lived. Tuesday had been there. Serendipity went there all the time. And these writers on the front of the newspaper had been there. But instead of coming safely home again, as usual, to sit down at their desks and transcribe all the things they had seen and smelled and touched and tasted and lived and imagined, something had gone horribly wrong. Somehow, on their journeys homeward, they had been knocked off course.

But no writer would ever tell the police, let alone the media, exactly what they had been doing before they were discovered in Madrid or Melbourne or Minnesota. Everyone would think they were mad.

“What do we do?” Tuesday asked.

“Well, I know what we don’t do,” said Denis.

Denis was at Tuesday’s desk, shoving pens and pencils and notepads and scraps of paper into his dressing-gown pockets. He tucked Tuesday’s little blue typewriter into its matching case and snapped the latch.

“No, Dad! Not my typewriter,” Tuesday begged, but her father was unmoved.

“Until further notice,” said Denis, “we do not write.”

Tuesday and Serendipity looked at each other. He might as well have told them not to breathe.