Baxterr knew too, and he dashed down the hill toward the fog. He checked that Tuesday and Vivienne were following, then plunged into the whiteness and disappeared from sight. Vivienne, reaching the edge of the fog, stopped in her tracks and began anxiously searching her pockets.

“The message…,” she said.

“It’s all right, I’ve got it,” Tuesday said. “Stay close.”

So thick was the mist that when Tuesday looked down at her own feet, she could barely see them padding along on the path made of uneven paving stones. If she held her arm right out in front of her, she could only just make out the star shape of her outstretched hand. This was a mist of an entirely different kind from any that Tuesday had ever encountered at home. The sort she knew and understood was damp and chilly, but this was quite dry and not cold at all. As she breathed it in, she was reminded of the fug in the kitchen at Brown Street when her father was baking with spices like cinnamon and nutmeg and cloves. Tuesday thought it rather lovely, but Vivienne was not impressed.

“Will this last long? I’ve had quite enough of mist for one day,” she grumbled.

“It’s not far. At least, I don’t think so,” Tuesday said.

“Ruff,” agreed Baxterr, who had doubled back to Tuesday’s side.

They walked for a few more moments before Tuesday saw two great white shapes materialize in the fog: they were marble statues, a matching pair of larger-than-life lions, each one with an impressive carved mane.

“There you go!” said Tuesday.

“Here I go … what?”

“They’re the beasts from the dog’s memory. Lions.”

Vivienne peered into the mist, bewildered, and Tuesday knew that if her father had been with them, he would have said that Vivienne was mystified.

“Where? What lions? Are you sure you’re not—”

Then Vivienne stopped, midsentence. She didn’t only stop speaking—she stopped altogether, as if someone had pressed a pause button.

“Vivienne?”

Tuesday shook Vivienne by the arm, but she was quite immobilized. Her eyes were half shut and her mouth half open. Tuesday felt panicked.

“Vivienne? Vivienne?”

“She will be quite all right,” said a familiar, steely voice from somewhere within the mist. “I must say, it was foolish to attempt to bring her here. I thought you would know better, Ms. McGillycuddy.”

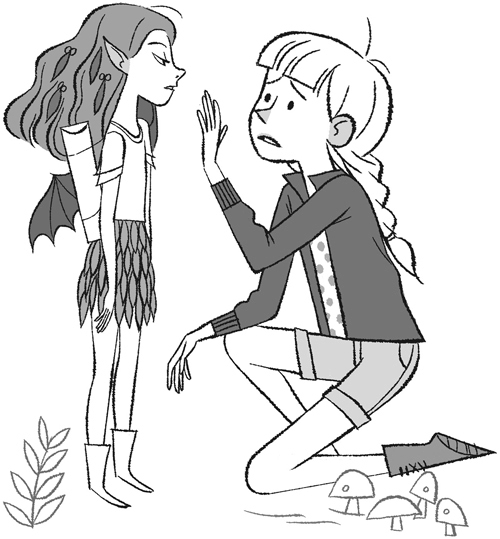

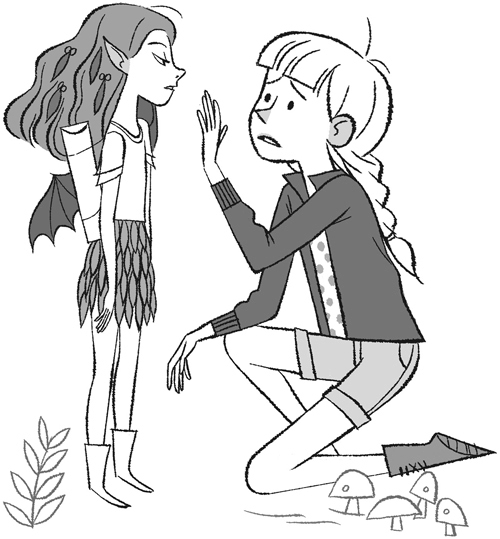

“Madame Librarian?” asked Tuesday, spinning about. The mist parted like a pair of fluffy white curtains, and there, standing on the path flanked by the two stone lions, was the Librarian. She was dressed from head to toe in her customary purple, but today, instead of wearing an outfit that most people would wear only if they were heading off to the opera, the Librarian wore a rather chic purple tracksuit with a patterned silk scarf at her neck.

“Vivienne cannot come here, Tuesday,” said the Librarian. “You have forgotten the most important rule of all. This Library is for writers only. She cannot see the Library. As you have discovered, she cannot even see the lions. Frankly, I’m rather amazed she was able to meet you at the tree. It goes to show how peculiar things are becoming around here.”

“What have you done to her?”

“Nothing serious. I promise you that she will be waiting right here for you when you get back. Come along, please. I admire your courage in starting a new story at this time, but you’ll need to take some extra precautions. So come along, and we’ll get you organized.”

Tuesday reached out to touch Vivienne’s cheek. Her skin was quite warm.

“Are you sure she’s all right?” Tuesday said, worried.

“Come along, come along,” the Librarian said, clapping her fingers briskly against her palm. “We have vastly more important things to worry about than the feelings of Vivienne Small.”

Tuesday was about to argue, but the Librarian’s piercing gaze made her knees tremble. The Librarian, although short, somehow managed to appear very tall. Tuesday straightened herself up, and she noticed that Baxterr was standing with his head held high, as if he too felt he must be on his best behavior.

“Good,” said the Librarian, then turned on her heel. She set off up the path at a rapid clip, and as Tuesday followed, she noticed that the Librarian’s usually perfect cap of silvery hair was a little out of place at the back. And although both her shoes were a very similar shade of lilac, they were definitely not a pair. Tuesday thought it best not to mention this.

“Madame Librarian,” Tuesday called after her, somewhat shakily, “I think you may be getting the wrong idea. I should tell you that I’m not here to write a new story. I haven’t even finished the first one yet. I’m here because a thread came to get me and—”

The Librarian stopped in her tracks and whirled around to glare at Tuesday.

“Oh, goodness gracious, Tuesday McGillycuddy. It seems to me that every time you come here, you are not writing a story. And yet a story came to get you, did it not? Hmm? In my capacious experience, I find it often happens this way on second visits. A story comes to get you, sometimes before you feel ready. But whether or not you felt ready, you did say yes to this story, didn’t you? You allowed it to bring you here, didn’t you?”

“I’ve just come to deliver a message, which I thought might have been for—”

“A message, hmm? What is a story if not a message of sorts? A message that you deliver not only to one person, but to all people who care to open its covers and receive it? A message to all people, for all time? What could be more wonderful than that?”

“I don’t have time for a whole story—” Tuesday began, but the Librarian interrupted her again.

“Time!” she said, indicating to Tuesday to follow along quickly. “Nobody has time to write a novel or paint a picture or pen a song. Can you make time, Tuesday?”

“I don’t think so, but—”

“No, we cannot, Ms. McGillycuddy. Time is simply there, and we choose how to fill it up. We sleep. And we eat. And we take baths and read books and visit with friends and have parties and—”

“Go to school,” said Tuesday. “That takes up a lot of time.”

“Ruff, ruff,” added Baxterr.

“Ah, yes,” said the Librarian, “and we frolic in the park, Baxterr. Good point. So, where, in amongst all of that, is the time to write stories, Tuesday?”

“Well, in between everything else?”

“And is that how you managed to write all you have? Did you fit it in between everything else?” asked the Librarian.

“Sort of,” said Tuesday.

“But not really,” said the Librarian, “because if I’m not mistaken, you got up early, and you stayed up late. You turned down offers to do all sorts of other things, and you wrote. Did you not?”

“Yes,” said Tuesday.

“So, you might say that although you didn’t make time, because the day was still as long as it was and the weeks exactly the same length, you made time for writing.”

“Yes,” said Tuesday. “But—”

“Do not tell me that you have to go home, that you don’t have time, because this is the time you’ve made, Tuesday, for this story. You have to live it. There’s no going back. There is only going forward.”

There was definitely an unsettling tone to the Librarian’s voice. She reminded Tuesday of Serendipity when she was at the end of a novel and hadn’t had enough sleep, and everything was difficult and confusing. The Librarian stared intently at Tuesday. They had arrived at the bottom of the great stone steps that led to the Library’s front doors.

The tinkling sound of a fountain reached Tuesday’s ears, and she caught the scent of roses. She noticed, however, that the Library’s gardens—which had been entirely manicured the last time she was here—were now a little disheveled and unkempt. As they climbed the stone steps to the front door, Tuesday saw the word engraved across the lintel: the word that Tarquin and Harlequin had glimpsed in the fallen dog’s memories. An enormous seven-letter word.

IMAGINE

Tuesday took a deep breath.

“Madame Librarian, I promised my parents I wouldn’t come here. Back at home, writers have been going missing. Writing has become … dangerous.”

“It is! Oh, it is! Make no mistake about that. It’s chaos!” The Librarian waved her short arms about wildly. “I’ve got a Library full of writers too frightened to even attempt to return home. I’ve not a single tea bag left, the Confidence Food ran out yesterday, and the bandage supply will be quite exhausted by this time tomorrow if things don’t improve.”

“Dad made me promise not to write. He made Mom promise too. We were trying to be normal.”

In front of the Library’s huge front doors, the Librarian stopped.

“Normal?” she said, turning to frown at Tuesday. “What in the dictionary did you think you were doing? Normal is not what writers need. Regularity, a set time to write, that can be very useful. But normality? No, there’s no adventure in normal. There’s no surprise or mystery, no villains or great love affairs, no tragedies or victories in normal. Normality is highly overrated, Tuesday. Eccentricity. Impulsiveness. Passion. Surprise. Joy. This is what a writer’s heart requires. And that most important thing of all—curiosity. Aren’t you curious, Tuesday, about the story that has brought you here? Don’t you want to know what happens next?”

Tuesday felt the Librarian’s deep violet eyes boring through her. She summoned her courage and reached into her pocket.

“What I do want to know,” Tuesday said, “is whether or not this is meant for you.”

At the sight of the scroll of paper on Tuesday’s palm, the Librarian gasped. She hovered one small wrinkled hand over the message. At last, she made up her mind to take it, unroll it, and read it.

Tuesday watched the Librarian’s face closely as she read the note. Once she had finished reading, she held it to her chest.

“Where did you get this?” the Librarian asked.

“Vivienne Small found it,” said Tuesday, drawing out the circlet of fine rope. “In the collar of a Winged Dog.”

“Where is the dog now?” the Librarian asked, taking the collar and inspecting the medallion with its engraving of a dog in flight.

“I’m sorry, Madame Librarian … the dog died.”

“Oh!” Tears sprang into the Librarian’s eyes. Still holding the collar, she extracted a lilac handkerchief from inside her sleeve and held it to her eyes.

Tuesday spoke gently. “So, the message. It was for you?”

“Yes, dear,” the Librarian said. “Yes, it was.”

“And do you? Do you have the answer yet?”

The Librarian tucked her handkerchief back into her sleeve. Without warning, she took a firm hold of Tuesday’s chin and turned her face this way, then that. She gazed deeply into Tuesday’s eyes. Then she glanced down at Baxterr, standing to attention at Tuesday’s feet. A shrewd expression came over her wrinkled face. She carefully returned the silver collar to Tuesday.

“Why, yes,” she said. “I believe that, at last, I do.”