The General was still sobbing when the mice heard the children making their way back from the assembly.

“I’ll think of something,” Tumtum promised him. Then he and Nutmeg fled back down the ladder.

As soon as they reached the floor, the gerbils hoisted it back up into the cage and hid it beneath their bedding. Then the door opened and Miss Short came in, followed by the children.

“Quick, this way!” Tumtum shouted, pulling his wife toward the wall. They ran along the baseboard, searching for somewhere to hide. But there was not a mouse hole to be found.

In desperation, they dived into a satchel lying open on the floor. Once they were inside, it felt oddly familiar. The canvas had been patched with gold thread, and there was a wooden pencil case with the initials A.M. scratched into the lid.

“Why, it’s Arthur’s satchel!” Nutmeg exclaimed. “I repaired it only last week. What luck, dear! This must be his classroom.”

“And we must be sitting under his desk,” Tumtum said. The Nutmouses crouched at the bottom of the bag, among the crumbs and the candy wrappers. All around, they could hear the sound of chairs and chattering voices. Then Miss Short clapped her hands, and the room fell silent.

“Now, class. I have an announcement to make,” she said.

Nutmeg wrinkled her nose. She didn’t like the tone of Miss Short’s voice.

“As you know, I have been wondering what to do about the gerbil problem,” Miss Short continued. “When they came to live with us, there were only two gerbils. But now there are twelve! Twelve gerbils, children! Just think of it! If they continue to multiply at this rate, we shall have seventy-two gerbils by next term, and four hundred and thirty-two gerbils by the term after that. And in a year, they will number two thousand five hundred and ninety-two!” (Miss Short was a math teacher, so she enjoyed these sorts of calculations.)

There were gasps all around the room as these extraordinary statistics sank in.

“But two thousand five hundred and ninety-two gerbils wouldn’t fit in the cage,” someone said.

“That is correct,” Miss Short replied. “And it is for that reason that I have decided to find our gerbils a new home.”

There was a chorus of groans at this announcement, for the children had become quite attached to them. But Miss Short was adamant. “Now don’t be sad,” she said briskly. “They will all be well looked after.”

“Where are they going, Miss Short?” someone asked. The Nutmouses, still hidden in Arthur’s satchel, listened anxiously for her reply.

“I am happy to announce that they are going to a pet shop in town!” Miss Short said brightly, as though this was a special treat, like going to the cinema. “I am going to take them there myself on Saturday when I go to return my library books.”

“Will they be kept together?” one of the children asked.

The gerbils—who, like the Nutmouses, had been following every word—all held their breath.

Miss Short hesitated. Until that moment, she had not considered whether the gerbils would be kept together or not. She did not think it of any importance.

“I imagine they will be split into different cages and sold in pairs,” she said finally. “I doubt anyone would want to buy all of them together.”

The gerbils did not like the sound of this one little bit. When they heard that their family was to be separated, they protested violently, hurling themselves against the bars, shouting and squawking as loudly as they could.

“Goodness!” Miss Short said irritably. “What a nasty noise they make. It’s just as well we’ve found another home for them.”

“What will happen to the mouse?” someone asked. Tumtum and Nutmeg recognized the voice at once. It was Arthur’s.

“The pet shop will find him a home, too,” Miss Short replied. “Perhaps they’ll even find him a mate. I’m sure there will be much demand for a mouse wearing underpants.” The Nutmouses bristled with anger, willing Arthur to protest.

And he did, for Arthur wanted the General brought home, too. It was his mouse, because it had been found in his cottage. It had been rather a nuisance there, it was true, and yet he felt protective toward it. And he didn’t see why Miss Short thought she had the right to sell it.

“I can take him home with me again,” he said helpfully. “He may as well go back where he came from.”

But Miss Short was not keen on this idea. “Don’t be silly, Arthur,” she replied. “You told me yourself that you have no cage for it, and imagine what destruction it might cause if it were to run free. Just think—it might multiply.”

“But I want to take him home with me,” Arthur persisted. “I wouldn’t have brought him here if I’d thought he was going to be given away.”

“Now that’s enough, Arthur,” Miss Short said crossly. “These creatures are all going to the pet shop, and that is the last I am going to say on the matter.”

There was a sudden racket from the cage as the General shouted something very rude at her—but Miss Short did not hear.

“Now, children,” she said briskly. “Let’s get out our math books, shall we?” And though Arthur felt very indignant, he hesitated to say any more.

Meanwhile, Tumtum and Nutmeg huddled in the bottom of Arthur’s satchel, their brains spinning. The town was ten miles away—if the General was taken there to be sold, he would never be seen again.

“We must think of something!” Nutmeg cried.

“We will, darling,” Tumtum said, but he felt a deep foreboding. Saturday was the day after tomorrow—they had little time. He squeezed his wife’s paw, trying not to show his fear.

“Oh, think, Tumtum! Think!” Nutmeg pleaded.

And think they did. There they sat in Arthur’s satchel, thinking all through the math lesson, then all through the English lesson, too. And then they thought all through the spelling test; and when the bell rang for break they were still thinking so hard they both jumped. But they still hadn’t thought of a plan.

They waited until the children had gone outside—less noisily than usual, for they were all subdued at the thought of losing their pets. Then, as soon as the room was quiet, the Nutmouses climbed out of the satchel and ran toward the cage.

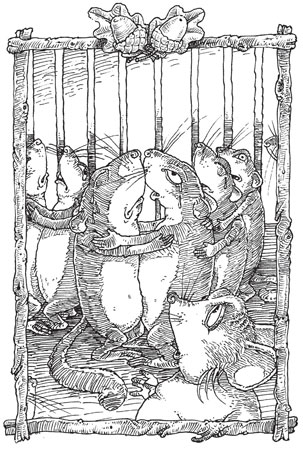

The gerbils tossed down the ladder, and when Tumtum and Nutmeg appeared they all threw themselves against the bars, clamoring for help.

“Do something, Mr. and Mrs. Nutmouse!” they cried. “If they split us up our whole family will be destroyed. We’ll never see each other again. You must help us. You’re our only hope!”

Tumtum and Nutmeg tried to reassure them, but the situation was very bleak. The only consolation was that the General appeared to be back to his old self again. He had stopped his boo-hooing, and instead was standing with one foot on the feeding trough, spitting with rage.

“A pet shop!” he fumed. “A pet shop! How dare that wretched woman presume to dispatch the great General Marchmouse to a pet shop!”

Tumtum turned to him as a sudden inspiration struck. “Do you think it might be worth calling in the Royal Mouse Army, General?” he asked. “They could launch an attack on the janitor next time he opens the cage.”

The gerbils all pricked up their ears at the mention of the Royal Mouse Army—but the General was dismissive.

“Pah! Do you imagine I hadn’t thought of that already?” he snorted. “I am confident, of course, that the Royal Mouse Army would send every soldier it could muster to rescue me. But there’s no point trying to summon it. All the troops are undergoing a week’s intensive pogo-training at Apple Farm— it’s nearly two miles away; they’d never get back here in time.

“And besides,” he went on, “there’s nothing the army could do against the janitor. He’s huge—if you fired a cannonball at him, he wouldn’t even feel it.” (This was probably true, for the Royal Mouse Army’s cannonballs were the size of raisins.)

As this one ray of hope was extinguished, the gerbils looked even more wretched. Some were hugging each other now and sobbing, dreading the parting to come.

Meanwhile, Tumtum and Nutmeg went on thinking. But even after thinking for another three whole minutes, which is a long time in a mouse’s life, they still hadn’t thought of what to do.