3

Shared-Gender Mystery

Of the many provocative sexological redefinitions that emerge from an understanding of eros as mystery, perhaps none is more fascinating than the notion that gender does not exist except as a shared elastic interdependency. In this light gender is seen as the fundamental condition of erotic embodiment that men and women find themselves in, rather than as a way to differentiate one from the other, or even to distinguish the specific behavioral patterns each displays toward the other. We will be entering gender as a mystery being shared.

Gender names that class of human phenomena that includes friend, partner, rival, and enemy. Like friendship or rivalry, gender reverberates between people, not in them. Gender always implies (with infinitely more cogency than the less alluring term selfhood) a mystery of ever more subtle rapports going on with another and with the world.

Gender is also a subject heading, as in “gender issues.” Only one other heading grasps as fully the integration of all constituent elements under its rubric, and that is the heading “ecology.” For example, while forest is a one-dimensional name for “an expanse of wilderness,” the term forest ecology is a multidimensional name that denotes an exceedingly dynamic interactivity and ever-refinable relatedness, even synchronous oneness. Change one branch, and changes ripple throughout the entire forest ecology.

Likewise, people may share many things (history, language, religion, culture), but when we refer to them as gendered people, their dimensionality suddenly and exponentially ramifies. Suddenly the sense of an elusive, shared mystery drifts among them (as it does in the ecology of a forest community). To understand gender, watch the more suggestive, subtle, and mysterious sharings among people (or any other life forms).

Gender is like the water two fish swim in that makes their play with each other visible and possible. It is the play or shared interaction of any two or more people regarding erotic mystery. Even our physiologies change distinctly and sometimes dramatically when we live with, or separate from, a lover. A definition of gender that distinguishes the composite traits of male-bodied persons from the composite traits of female-bodied persons (that is, gender as specifying gender differences) is very persuasive but is insufficient to deal with the interactive reality of gender.

MALE AND FEMALE AS STARTING POINTS

The terms female and male are merely starting points in the life of gender and imply a relatedness between a man and a woman or between two women or two men that is different than the relatedness between a twenty-year-old person and a thirty-year-old person. Reading a story about a person, rather than about a man or a woman, provokes scant erotic mystery in the reader (except in the way that the term person is itself an alluring veil).

But as soon as we say that a woman reads a story about some person, a little more of the erotic mystery begins to stir. And then the person in the story turns out to be a man. But then the woman reader is a lesbian, while the story-male, as in a Shakespearean drama, is really a woman. A woman who is attracted to . . . we can go on and on tracking the crests and falls of shared-gender permutations in which male and female are purely suggestive of something or other but are meaningless in themselves—in an inevitable and inescapable process of shifting nuances, possibilities, and plot swervings.

I can think of no more tragic an example of the scientia sexualis mission of assigning each person a proper gender (even the liberal attempts at LGBTTQI categorizations retain this trope) than as can be seen in the diary of the nineteenth-century hermaphrodite, Herculine Barbin, written at the time when the medical scientia profession first took up this categorizing task. Brought into contemporary awareness via its publication and commentary by Michel Foucault, the reader of Herculine’s diary traces the innocent frivolity of female-seeming Herculine among her young girl students suddenly anatomically “examined” and “determined to be a man,” whereafter Herculine’s story is amplified and spun through the sensationalizing tabloid journalism of its times, she is fired, suffers a complete mental breakdown, and commits suicide.

GENDER IS THE SHARING OF MYSTERY

Gender is itself the sharing of mystery. Gender is something we are immersed in profoundly, and mystery is the experience of profound immersion in an alluring uncanniness. This is the particular beauty of the term gender: It points to the erotic immersion that we all share. Just walk down a busy street and feel the interactivity of gender mystery. Feel the awe, suspense, curiosity, and spontaneous allure—cues that we are immersed in a shared mystery.

As we shall see, our erroneous conventional understanding of “separate genders” or gender as gender differences is the fault line of anguished tumult between men and women in our contemporary erotic world. Our problems with gender are fundamentally conceptual and then perceptual; we have expunged sharedness from the concept of gender and have expunged mystery from our too certain perceptions of sharing and being. Only a contacting of one another in careful wonder can re-reveal “sharing” and “gender” as indivisible.

To understand sharing is to understand gender, but it is not the active-voice transitive verb, as in “He shared his seat with her” or “She shared her ideas with him” or even “They shared their resources with each other.” The sharing I have in mind is not wielded by anyone, for the sharing of gender is a fully interactive condition that we, as men and women, find ourselves in, not a set of stable traits or behaviors inherent to one or the other.

Sharing is the realization or perception that with reference to gender, men and women are in an ecological or “same boat” situation with one another. It is this realization that provokes a sense of awe, dread, relief, or respect, for shared interactive gender makes us inherently committed to one another. The inescapability and the equal degree of being in this gendered condition are what make it a shared condition. Gender, like procreativity, is an inexplicable trust given to us. It is a trust in the sense of being a reservoir of possibility, as in a trust fund. As well, it is trust as a magnetlike, inherent holding together, felt as an uncanny connectedness, an allure, a hope, and, most certainly, a need.

If the criterion for being a romantic-erotically lovable and loving person were to be ars erotica entheogenic maturity, then such would become the basis of cultural erotic sharing, en masse, for that culture and scientia sexualis would fade into the “old way” that people “used to share gender.”

Sharing Lost . . .

Even if men and women speak and act as if gender is not an utterly shared trust, we are still in it as our given condition. We then share the lack of this recognition. We share it just as blacks and whites, Arabs and Jews, rich and poor must share any lack of recognizing certain truths regarding the shared human trust called specieshood. The problems that emerge in such contradictions breed in the contorted but unavoidable sharedness that still remains.

If one boat mate says to the other that she is not getting what she needs from the other, what she is doing with the shared condition is seeing a problem and announcing it. The two now share (intransitively) and interact regarding the complaint “My needs aren’t being met.”

The deeper problem for this pair is that the sense of sharing the same boat on the same deep waters is in jeopardy of being swamped by the emotions stirred by the complaint. What if they lose sight of the irrevocable sharedness of their situation and think the single thing they share and now must do something about is the declared problem of an unmet need? What happens? The way of differences unfolds.

Gradually they will come to believe that they are not in the same boat at all, not even clinging to its turned-over sides together. They begin to think and feel and speak to each other as if they are in different universes. Instead of sharing this dubious feeling of being in different universes, they start to measure and dogmatize their observed differences, perhaps as gender-based, irresolvable differences, and wonder if they have ever shared anything but differences! They then start to live as if they are in two separate universes, reaching over the wall to make any contact. Thus devolves the vivisection of the shared-gender mystery. In the gaping expanse of this preoccupation with differences, dark fears seem to look back at us. What Jung termed our own “shadow” meets us.

Disparities in societal opportunities solidify; moods of superiority-inferiority infect. The beauties and risks of flirtation become suspect, exploited, and compromised. The significance of gender itself feels so insufficient that men and women resort to exaggerated mythic images—the “wild-men,” the “wolf-women.” Love itself feels so dangerous that authorities apply the concepts of addiction to much of romantic life—and they are believed, as the proliferation of (gender-based) support groups testifies. As the fluid play of shared gender rigidifies, we lose some of our sense of humor and political correctness, moralism and ensuing fears of “men” and of “women” lock in as each jolts, seeing the other’s look of suspicion aimed at himself or herself and peering back out of one’s own eyes. Even the eye-quavering looks of desire and allure seem dangerous. Indeed, the innate safety that otherwise comes from mutual gender respect before each other as life-creating mysteries seems to be thousands of impossible miles away. I suddenly recall, decades ago, being in a remote village in India. A ten-year-old girl appears out of nowhere, innocently starts dancing classical Indian movements and singing in front of me and an Indian man as we chat on a park bench; she smiles at us and dances away. Thousands of miles away from these modern, fraught, and fearful scientia sexualis times, indeed!

Homophobia emerges where compassion fails regarding HIV. Not a single new thought on the abortion debate emerges; instead, battle lines are drawn more deeply. A symptomatology of divorce, rape, batterings, misanthropy and misogyny, and victimhood precipitates. Millions of people recount painful memories of childhood sexual abuse, numberless others report incidents of sexual harassment, and in this confusion still others retract specious complaints based on false memories of sexual abuse.

. . . Sharing Found

Certainly the final mapping of the phenomena of gender (and the solutions to the above conundrums) will not come through yet another investigation of the differences between men and women. The map, and solutions of any depth, will come only through the comprehensive study of gender as a conjoint and mysterious sharing of erotic powers, for that is what gender is. Framing the research question in terms of contrast, such as, “What are the differences between men’s and women’s abilities, linguistics, or attributes?” ruptures the in vivo phenomenon that is being approached.

Adherents of these findings on why women are thus and men are different at first feel empowered by their “verified” specificity. They enjoy the explanatory power of the discovered differences and employ this information in daily life with hopeful conviction. Later, which for our culture is now, they begin to feel the limitations of these gender objectifications: the stereotypes are discerned and resisted; the panacea fails to deliver. In spite of all the best-selling reports and studies, the demystifying method guaranteed as much from the onset, for these findings are often little more than shadow measurements in the proverbial Platonic cave.

Those who would study gender as a shared reality, like those who would attempt to feel the heat of the Burning Bush, struggle with more mysterious problems outside the cave, in the dizzying radiance of living gender powers. In the ars erotica, every solution to a problem of gender spirals into a more intricate sense of sharing.

The question must be asked, “Why might individuals want to define genders based on differences?” The answer will inevitably imply difficulties with sharing, overdetermining theories of “individuation,” entrenched cynical certainties, and a fear or denial of even fleeting spiritual responses to the other. Such difficulties are not a function of gender differences but of the uncanniness of sharing uncertainty, suggestivity, subtlety, and mystery. Questionings intoned one way will seem to lead us to convincing literal answers, or intoned another way, to awesome experiences of the incomprehensible. The former emerge from scientia sexualis, the latter from ars erotica. We must recover through intimate and artful means the wonder of, not information about, one another. Awe, not certainty, signals that we are gaining knowledge about gender.

Even our “own” gender is inextricably rooted in the combination of our two parents’ gametes, while the seeds of our children’s possible lives tingle mysteriously in our bodies, awaiting deeper contact with the seed of some other. The biological believe-it-or-nots of gender amorphousness—the hermaphroditic phase of normal embryological development, the rare but real adult hermaphrodites, and the various gender transmutations of the greater plant and animal world—should give us some pause. Heterosexuals fail to learn anything new about the fluidity of gender from gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered persons. One wonders if we will ever leave the shallows of “sort-and-file” gender enframement for the more mysterious depths of an utterly shared gender.

Even our observations of other cultures and species have been made through these gross lenses. Monkeys grooming and preening one another, the vast array of animal mating behaviors and rituals, and the cross-cultural diversity of social-erotic customs are best described as an ever-changing, interactive play of gender, not as “male behavior” and “female behavior,” nor as a primordial scientia sexualis polyamory. But the scientist of gender asserts, “The female always does the x behavior, and the male always does the 1/x behavior; therefore, there are two distinct genders.” No: x and 1/x are functions of each other; they are mutually variable with regard to each other and thus determine each other at unfathomable levels of pheromonal and interactive rasa subtlety.

Even the idea that each person can be pegged on some kind of continuum from ultramasculinity to ultrafemininity is only relatively useful. Androgyny, the synthesis of masculine and feminine qualities in any person, still locates gender within a sort of psychic bisexuality and is only a symbol for the living condition of shared gender. The principles of social systems theory, in which roles and meanings are understood as group phenomena, can provide some insight into the fact that the significance of a person’s gender is shared by the group, but not strongly enough to make the radical leap we now approach.

What we are looking for is a fundamental ecology of gender and a romantic and erotic sense of this ecology in our relationships. For shared gender is not just a partnership, as Riane Eisler proposes in The Chalice and the Blade. This cooperative, same-team metaphor misses the profundity of how deeply and indistinguishably the roots of gender entwine and tendril into the ground of our existence.

Partners who cooperate together, who get paid equally, and who worship goddesses as well as gods might never know in their bones how very shared and alchemically, reverberatingly, and mutually empowering the condition of human gender is despite the intermingling closeness that sexual intercourse inherently is. The kind of knowledge of each other that I am speaking of is different from all of that. It is a knowing that is verified when it provokes a spiritual response of each to the other: a mood of devotion and reverence that trails into shy astonishment and ever-more-empowering displays of passion, with the entheogenic response of allowing our lover to make us feel we are completely beside ourselves, witnessing god or goddess in human form sitting there radiating all the charms of the universe before our very eyes, loving us with a love supreme, evoking play-of-the-gods dances in romantic-erotic repartee, ars erotica actions, grihastha home creations within the shared confidence of “Yes, yes, yes, till death do us part and again, yes!”

Really mean it till death do us part:

Holding your wrists you writhe slightly this way then that

your outer surfaces contiguous with the invisible realms of you

giving rise to a path leading to surrenders

you squeezed my hand I give up, your hips raise to one side

you bite gently your own lower lip press your finger

as if to silence the gasp of it all fainting into yourself

into the infinity of the future uplifted into a haze

we entered the subtle realm where starry everything glows.

Each preferring to give, nothing was ever lost,

stretching ourselves thin for one another we became vast.

Easing the way for me for you as the decades wandered on

no sorrow or illness endured alone,

parents aging before us and dying, friends passing, all

eventually pass.

When you squeezed my hand hard and held it there

the day I got that dreaded call, I will never forget it—

I am here, you said, I am not going anywhere,

and when my grip weakens, then my gaze upon you will lock,

when that at last should blur,

then resolute in my heart shall you remain,

your name the last sound on my lips,

your lips the last image in my mind . . .

While give-and-take partnering and cooperation is a common understanding of sharing, it falls short of perceiving gender as a shared mysterious reality and then living up to that perception. All such concepts as give and take belong to the materialistic realm of economic exchange and fail to settle into the more ontological potencies from which gender manifests—the spiritual economy: nemein, a disbursing sharing, within the intimate place of sharing, oikos, the home.

Instead of wonder and awe at the reality of shared gender, we usually seek literal answers to our questions about this mystery. We believe knowledge comes from demystification, which, in the domains of eros, can be fatal. In our current world—where eros is demystified as ultimately meaning a well-defined desire—gender definitions turn out to be what we want genders to be like. Gender gets caught in desirability, and its mystery is shaped likewise.

We do not relate to gender as shared mystery but as specific need-fulfilling commodities (we are to “meet needs”), explanatory resources, and vested-interest groups. We think of gender as a given that can be used to explain why things are the way they are; it’s this way because of men, because of women; the one must change; the other; no, both must change.

The historical record reveals our difficulties with gender and the sharing of social power, but not the more subtle spiritual history of the fall of gender-as-shared-mystery into gender-as-assignable-differences. In “tantric genderosophy,” we see that we do in fact call forth or limit the possibilities for one another’s gender (for any particular time span). Yet tantra takes its stand upon gender as a shared mystery, the recovery of which provokes an inherent awe and spiritual respectfulness of one another. Such provocative spiritual knowledge can form the basis for social and political revisions, just as the plea for a “deep”—that is, spiritually provocative—ecological vision can provide the internal motivation for needed environmental protections.

GENDER AWE

The inequities between the genders, currently discussed as the history of patriarchal dominance and sexism, cannot be reversed merely through scholarly research, as some might hope, nor through political initiatives, as many demand. Spiritual problems, even if they also foster material inequities, require spiritual solutions. Sanctity can be neither proved nor legislated and lies beyond anyone’s political agenda. Reverence is always an unrequested response to another who is perceived as being beyond all of our scientia concepts and estimations. We must let the other mean that much to us. Typically, forgiveness, contrition, and reconciliation wash through worshippers in these moments as well. Such is the transformative potency of a spiritual resource.

Certainly, reverence does not belong more to the one gender than to the other, nor does it belong to those who worship gods rather than goddesses. For it is not the form or gender of the deity that matters but the depth of the reverence its devotees bestow upon it.

If reverence be profound and ever-spreading of its blessings, one can worship a cobblestone—humility may, after all, be divine. We can recover the birthright or trust given us as gendered creatures only through the holy recognition of an utterly shared gender.

These feelings are not some kind of rare luxury that only a few select individuals deserve, nor are they rarefied emotions to be reserved for special occasions. The situation is in fact the reverse: reverence is the only sentiment we do not earn. It is the universal response to the other as the mystery that she or he is, just for being “the other,” the starting point for ars erotica mutually provocative wonders.

This is the deepest erotic opportunity we provide each other: to be humbled and exalted reciprocally. Quietly watch the other’s sleeping face for one minute. The mystery is not far away. This overlooked nearness is our tragedy.

As for reverence being a luxury, would that were true, for whatever we shy away from worshipping inevitably atrophies and lives on in an ever more withering state. Thus the future of gender is itself at stake, and it shows. We have turned away from the deep beauty of one another and no longer worship one another or the earth we walk on. Instead, we rest upon the “surface” tumescences of desirability, shying away from those arousals of awe and surrender. Only worship of one another is profound enough to call forth the deepest of human possibilities, and only the depths of possibility provoke our awe. In erotic reality, possibility and mystery stand higher—have more alluring “life” in them—than actuality and certainty.

Admiring one another, struggling and accomplishing together, come and go as talents, crises, and projects come and go. These are responses to life’s actualities. They are well worth exploring with one another. But more alluringly mysterious is the reverence for another essentially because she or he is other, because dawning in the other are living, yet uncertain possibilities. Self-worship is viable, but only in the same way another can worship us: we must stand back in awe, humbled by the inherent holiness we radiate upon one another. We can create or at least nurture life and have been created by seed forces that genetic science can trace but not explain. We come from something very, very Deep.

GENDER WORSHIP

Worship is what even the immortals long to do, and they willingly relinquish their immortality in order to find something to bow to. What they long to worship is the other, not themselves. Thus, the immortals become the other—that is, mortals—in order to carry out their sacred rites. They become us, we become them, over and over again.

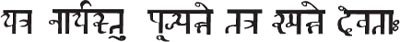

Where man/woman is worshipped is the play of the Divine”

This is the crowning touch to a recentering of eros with mystery: We discover through a devotional meditation, or other such means, that, erotically, we are in a shared mystery together, that all the psychological interpretations, desires, fears, and expectations we have about each other merely circulate around the inexplicable mystery that every man or woman is.

“Filled with joy” is such a ringing singing phrase.

Like shiny brass turquoise and garnet bejeweled Tibetan icon couples

in upright thrilled embrace, blossoming in those icons

secret truths mystico-erotica original religion

fully-matured upward inward all glands alive tumescent engorged

totally intent the one upon the other

perfectly in love

designed by the cosmos

each quantum crystal species plant animal male and female

to capture the full attention

the one of the other the other of the one

in perfect symmetry.

If we are unsure whether our devotion is authentic, we must take it on faith that it is, for it is greater than we are at those times. Our worship of each other will frequently be a mystery to us, particularly when we don’t believe this is possible. In such uncertainty the mystery has a chance to grow, our faith has a chance to grow.

We also allow ourselves to be worshipped, not as a great person but as mystery; that is, for reasons we may know nothing about and must therefore take on faith. Meditative worship is the opportunity for each of us to transcend our conditioned beliefs about each other for some moments, even amid the most trying times of a marriage or relationship, and to experience the mystery that lives in spite of the dramas and crises. It is a return to the possible as real and to the hidden as a promise. Thus we recover the reverence that can be obscured by fearfulness.

Worship is merely the response to the perceived erotic truth of the other and not a strategy to some further ends. It is certainly not a requirement, like routine church attendance. It is the most profound and enigmatic expression of the shared-gender mystery. And charismatically shaking, playfully wild, seed-rasa-mudra-activating worship contains its own overwhelming motivation to attend the Church of Endless Ars Erotica.

Whether the privilege of worship rests with the worshipped or the worshipper is altogether unclear; it is even unclear whether there are such distinctions at the core of the shared-gender mystery. As you will see, the love-making practices of tantric brahmacharya hover in this uncertainty, in the partners’ ever more vulnerable and empowering intimacy with each other. As you discover worship of each other in some mundane moment, such as when doing the dishes, watching TV, or feeling resentful, you will go even deeper into this tantric paradox of holiness hidden everywhere.

The seeming risk is for the partner who makes the first offering to the other, without any concern for reciprocation but merely as the immediate recognition of the holy mystery of the other and the opportunity this holiness provides for us, originally and eternally. When we contact the erotically worshipful in each other, we must face the ironic fact that it has always been there and in ourselves as well.

THE PROSTHESIS OF AN OWNED SEXUALITY

Even the notion of one’s “own” sexuality is a politicized derivation or appropriation of eros, a personal act through which one hopes to attain a sense of being an autonomous agent. As a collective, public act, the proclamation of an ownable and owned sexuality is intended to redress previous inequities by producing socially recognized personhood, as in the inspirational slogans “Woman Power” and “Gay Power.”

We would like to own various powers, and popular psychology supports these aspirations with its encouragements to “reclaim” or “own your sexuality.” But the erotic powers of sexuality—love, attraction, arousal, fertility, families, and surrender—are entrusted to us or, rather, among us and are not “owned.” Such slogans are merely transitional metaphors or therapeutic word tools to help us recover from domestic violence, depression, social-political abuse, low self-esteem, or drug addiction (in which heroin and amphetamines play the role of the greatest rip-off artist of ars erotica’s natural ecstatic chemistries for users and of the ever-forgiving loyalty chemistries of their “codependent” closest ones) or alcoholism (in which alcohol is rasa rip-off artist number two).

Such terms belong to the technologies of recovery and rehabilitation. Although the image of an owned sexuality can be a temporarily effective prosthetic word tool, it should not be used in mapping the intimate contours of erotic space, for prostheses and maps serve entirely different functions. After we have recovered, we must put away such prosthetic devices, for we cannot pass through the eye of the needle of intimacy carrying our own sexuality with us. When two give to one another, love becomes infinite.

We are for ourselves best when we are for each other,

a lifelong exploration of the preposition for

humble overlooked what are things for

a yearning, I am in love with for,

giver beyond myself bowing, finally, in devotion

each other granting exquisiteness to each other,

really meaning it,

becoming symbiotic with you, source of my awe.

Orienting the minutes hours toward you,

the purpose to get up early to listen to you breathe,

as the day finally ends racing stop lights to get to you,

you say when I don’t know what else to say I say, you you

I say yes yes.

It might be just as helpful for some people to hear that they needn’t worry about owning a sexuality or not owning one. Often in such cases when people have suffered abuse, they need merely to learn how and when to say “no” or “yes” to others within the context of the shared-gender mystery. The deeper goal implied by this quest for “personal power” or “reclaimed sexuality” seems to be respect, and an appeal to surrender to an ecological embeddedness of all relationships (especially those of romantic love and family life of children, grandchildren, and grandparents and so on) in the Whole.

Respect for each other is most authentic when it is a secondary response to feeling the awe and vulnerability of the other or oneself. Respect for our own erotic nature is a matter of being moved by the lyrical romanticism—the spirit—of life that we, as humans, are entrusted with, as our collectively shared and interactive nature. When charismatically energized, respect for one another gives back one hundredfold in mutual entheogenic rasa interactivities. We become god/goddess dancing endlessly with one another.

No one owns any part of nature’s spirit or its powers and beauties. If we can discover the poetry of nature (human-erotic and otherwise), what it is we seek through “owning” it or “reclaiming” it will have been accomplished: a kind of ecological—that is, respectfully shared—balance of self-and-others, of humanity-in-the-world, that will always remain somewhat beyond our control, as mystery. In fully matured conjugal urdhvaretas, the power of the shared-gender mystery unlocks ars erotic heat that owned sexualities cannot ignite.

In the rough-and-tumble world, arming ourselves with the idea of an owned sexuality and gender may feel like an attractive strategy. The more you feel you “own” your “own sexuality,” the easier it is to divorce or break up and pack up and leave; thus, prenuptial agreements seem like a self-protective “good idea.” The less that children are understood as being born of the flesh of “two become as one flesh,” the easier it is to see “split-time, coparenting” as a reasonable and ever more common parental structure. Yes, as an over correction for the church’s scientia of sacrificial love, self-affirming and more calculating scientia sexualis psychologies have been fashioned, with good cause, since we might give a lot to someone yet receive back a pittance. But as Rilke has said, “In the end it is our unshieldedness on which we depend.” Unshieldedness is a sufficient stance only when we have grasped our final essence as being infinitely resourceful—that is, in our discovery that humans are souled beings. We have an ultimate meaning and innocence that cannot be taken away, for it is inseparable from us, even by death. Merciful and ever forgiven, we ring with soul. Can or will we see each other—and be seen and feel seen by each other, and gratefully so—as endlessly resourceful souls? And in such wholly commingled seeing-and-feelingseen, how can we not but want to leap into unreserved commitments and a deeply ecological interconnectedness with one another in our romantic and familial relationships, until death do us part?

Under even the most tortuous of conditions, the soul replenishes us, not omnipotently but inexhaustively. Thus, the higher spirit of tragedy: the strange capacity to endure and live through untoward and even cruel hardships is part of the human condition. Often it is tragedy that surfaces the soul-sense as being deeper than the personality-self, the soul’s everyday agent. We discover that we are more than our personalities ever thought. Popular psychology’s concept of the “survivor” of past abuse is further cleansed of victimistic overtones within the spiritual psychology of soul. The soul as our essence radiates an inherent dignity untouchable by worldly abuse.

A dread accompanies grasping the awe of the soul’s capacity to endure all, for the implication is that if the dreadful were to happen, we are capable of enduring it and thus we would go through such unthinkable fires, unavoidably. Such strength is not good news for the limited personality-self of psychology, and rightly so. For the limited personality-self “knows” with great terror that it cannot endure the most dreadful of possibilities. We must know the soul to grasp the depth of such fortitude, a knowledge that would radically transform most of contemporary psychology.

Cut off from a sense of the enduring spiritual resources of the soul, our demystifying psychology has come to believe that the personality-self is best restored by creating strong boundaries around its periphery and “owning oneself.” But boundaries is merely another prosthetic word-tool, a crutchlike means to some end; certainly it does not accurately map erotic reality.

As Martin Buber has stated, “Every It is bounded by others; It exists only through being bounded by others. But when Thou is spoken, there is no thing. Thou has no bounds.”1

The goal is not to build boundaries but to feel respect and share it with others. This goal is better obtained by fathoming the spiritual fortitude and uncanny resilience of the awesome soul that is our essential nature. When the charismatic energies of Shiva-Shakti emerge, sharing replaces the prosthesis of “boundaries” with the profuse abundance of entheogenic co-creativity, equal to a lifetime of unbreakable sharing.

The recently coined metaphor of “soul murder” is a particularly costly overdramatization used to emphasize the horrifics of interpersonal mistreatment (and perhaps to deter future perpetrators). Unlike the body, however, the soul cannot be murdered, nor can it be “wounded” to later “survive” such blows. Devastations, abuses, and crises are obstacles that, when dealt with from the integrity of the soul, will mature and soften us—sometimes even unite us in a transformed relationship with our adversaries.

Thus, the key etymological secret power in the word soteriology (spiritual salvation) is te, which refers to tumescence, swellings that arouse the soul’s power to heal oneself and become even stronger than before. The ancient Greeks knew—as did the early Christians, who also made use of this term for “redemptive healing”—that forgiveness, love and caring, apology, gratitude, faithful longing and persevering, moods of awe and humbled reverence, righteousness of any clearly justifiable outrage (such as being righteously outraged by apartheid or any unjust actions), and giving and sharing are far more important than the scientia sexualis–favored clinical emotions, the “letting out” of sheer anger (emptied of its driving reason), grief as cathartic crying (rather than lost-forever love), boundary assertion (instead of respect creation, charismatic interactivation), sex desire (instead of seed-infused, profound-pleasure creation), and so on.

While the popular clinical concept of wounding provokes a kind of pathos that leaves us less than we were, that of an encountered “obstacle” engenders a daring and suspenseful response in which we remain whole and challenged to continue to participate in our lives. Thus, we have, on one hand, the labeling of our difficulties as a wounding or a murdering, requiring a shoring up of boundaries (against the “other”) and an owning of one’s power (taking it back from the “other”). On the other hand we see our difficulties as obstacles that draw out the more hidden powers of our souls in unshielded living within the strangely vulnerable mystery of reciprocal awe for one another. The differences between these two linguistic routes through adversity could be all the difference in the world, for each leads to the creation of a different kind of world of selves and others. As the great linguist Ludwig Wittgenstein noted, “to imagine a language means to imagine a form of life.”2

HOMOSEXUAL MYSTERY

From the perspective of ars erotica, we are homosexual as soon as we like another man or another woman. It is only through the reduction of erotic mystery to sex desire and, perhaps, to fertility that homosexuality becomes difficult for many heterosexuals to fathom. Why are men attracted to other men with a sex desire, why women to other women? For that matter, why are men and women attracted to one another?

The answer is again a matter of wonder and amazement, and psychological, biological, or religious concepts merely obfuscate the uncanniness of erotic attraction with their interpretations, research findings, and judgments. The path that seems to lead one to the persons he or she loves is as many-layered and enigmatic as the currents of the oceans.

The capacity to see beauty in another to the degree that passion arises is a sign of individual sensitivity, for it is our surrendering that makes the other attractive, as much as it is another’s beauty that induces us to surrender willingly. Two men or two women can even feel the home-building passions of fertility stirred by each other within the context of their sharing of gender, as well as the passions of desire and sublimation. They may partially or openly grieve that, just as with an infertile heterosexual couple, the mystery denies them conception. They share this limitation.

Coded cues of seduction and drag disguises that reveal the “true self”; ultraguarded privacies where one’s home has been a closet; one’s loving as a private struggle to accept and then, one hopes, to enjoy; a “difference” from others described by them but hidden from oneself: such are a few of the ambiguities of hiddenness in the homosexual mystery.

Within the ars erotica yoga of emotions known as bhakti devotional yoga, gender gets even more profound and diverse in the tradition of gopi-Krishna worship, wherein all humans are considered to be “female” gopis (cowherd girls) longing for the Male-Beyond-Male Deity, Lord Krishna. While traveling in India, I came across a small band of such sari-dressed, smilingly shy, and cosmetically beautified gopis, living beyond any scientia categories of “males who cross-dress as females.”