“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion starts her first essay in The White Album1 with this sentence, detailing our human instinct to make sense of the incomprehensible, to link life’s naturally disparate scenes with a narrative thread. On instinct, we fill in the blanks to create stories and these stories then create our realities. Whether we know it or not, we are always telling stories.

We share these stories in every moment in myriad ways; it’s human nature to do so. We live by these stories and extract our ways of being from them. We shape our experience through the lens of stories and often try to shape another’s experience through that same lens.

For much of human history our stories were shared orally. Later, forms of writing appeared, followed by the creation of the alphabet, printing, and finally digitization and the internet. Words took flight on a global scale, bringing stories in increasingly efficient ways to a wider audience.

This timeless urge to share our stories has sparked the greatest technological innovations, like writing, the alphabet, the printing press, and the internet, as mentioned above.

Our stories have formed the foundation of civilizations, incited revolutions, and restored stability during times of unrest. Whether fiction or nonfiction, our history is indeed written in stories.

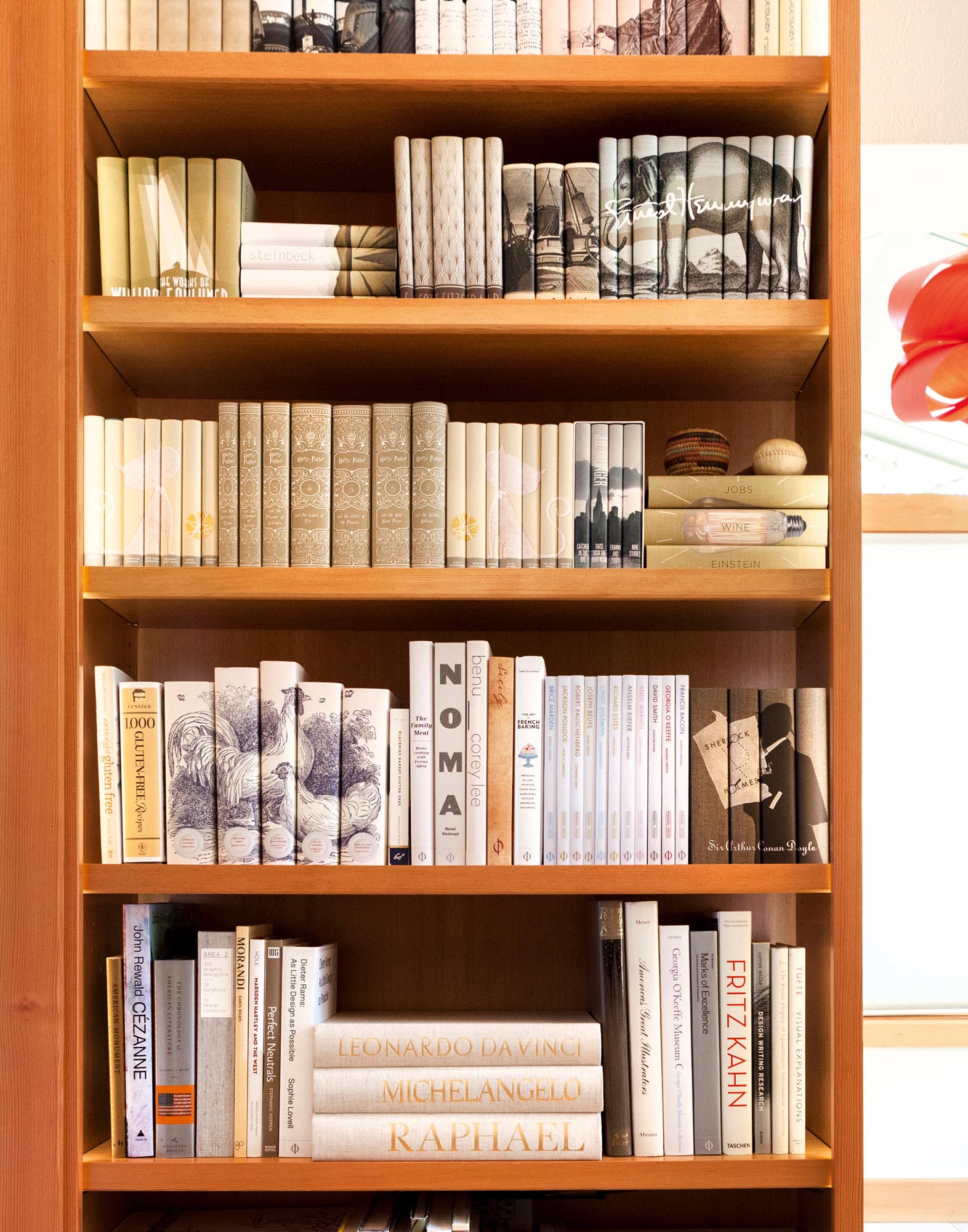

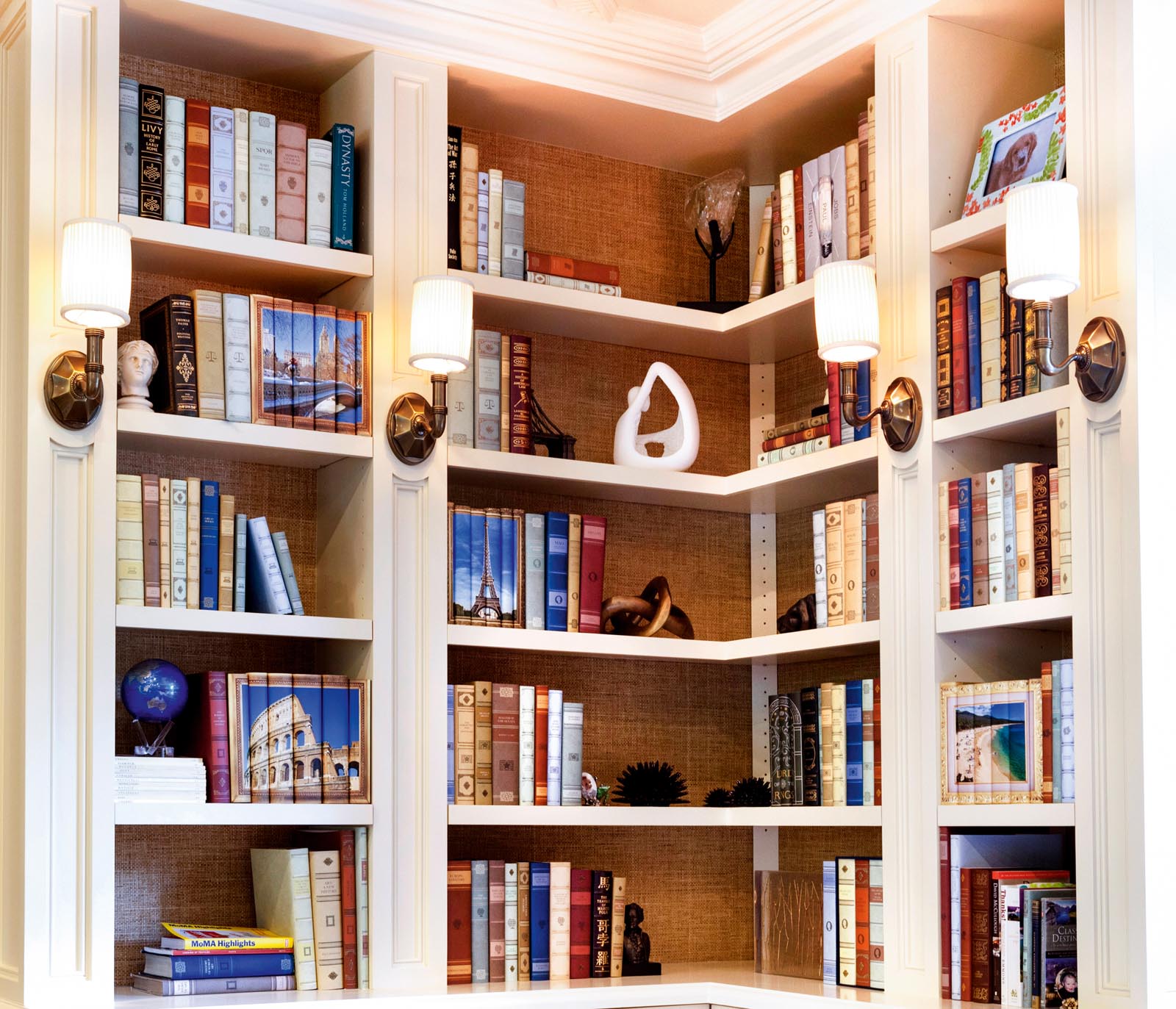

However, our storytelling does not begin and end with words on a page. The idea that a collection of books or a library can tell the story not only of civilizations, but of us as individuals, is a theme that we will come back to many times throughout this book.

For every printed book (or clay tablet, papyrus scroll, or hand-copied manuscript), the written word has proliferated from one person (the author) to many (the readers). The places where these works have been stored each contribute their own piece of the text’s story, whether it is a government repository, a spiritual archive, a community library, or a home bookshelf.

The story of each place is unique. For example, a library that holds a first edition of The Great Gatsby has a different tale to tell than one that has the paperback edition circulated in high school classrooms. The location, how the book was acquired, and where the book is placed among other books and personal items all enhance our experience with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic work. The story is not just his—it is ours.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live. . . . We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely . . . by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria—which is our actual experience.”

—Joan Didion, The White Album

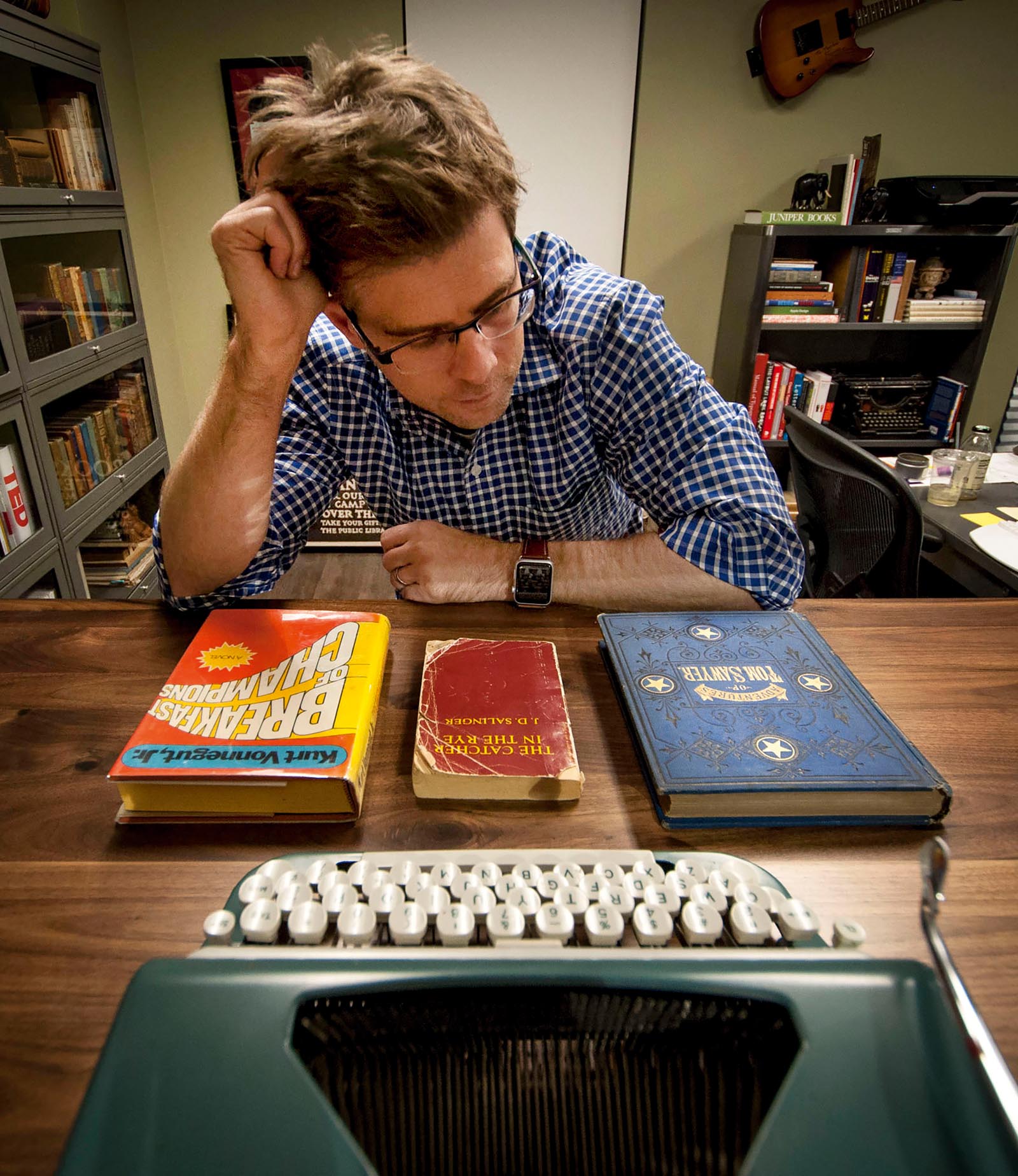

When we add books—any printed books—to our homes and lives and make space for them, something almost alchemical happens. We combine the author and their story with who we are and our story. The combination of the author and their story plus us and our story is a new story, and it’s completely original.

Like our DNA, the combination of books we keep cannot be replicated by anyone else. Even if others have the same book titles as us, their books have different meaning to them. By holding books in our hands for hours as we read them, we develop associations that last forever: where we were when we bought the books, who we were when we read the books, where we keep our books, and how we organize them.

The books we keep are so much more than the stories on their pages and the titles on their spines, they are reflections of our choices, our preferences, ourselves.

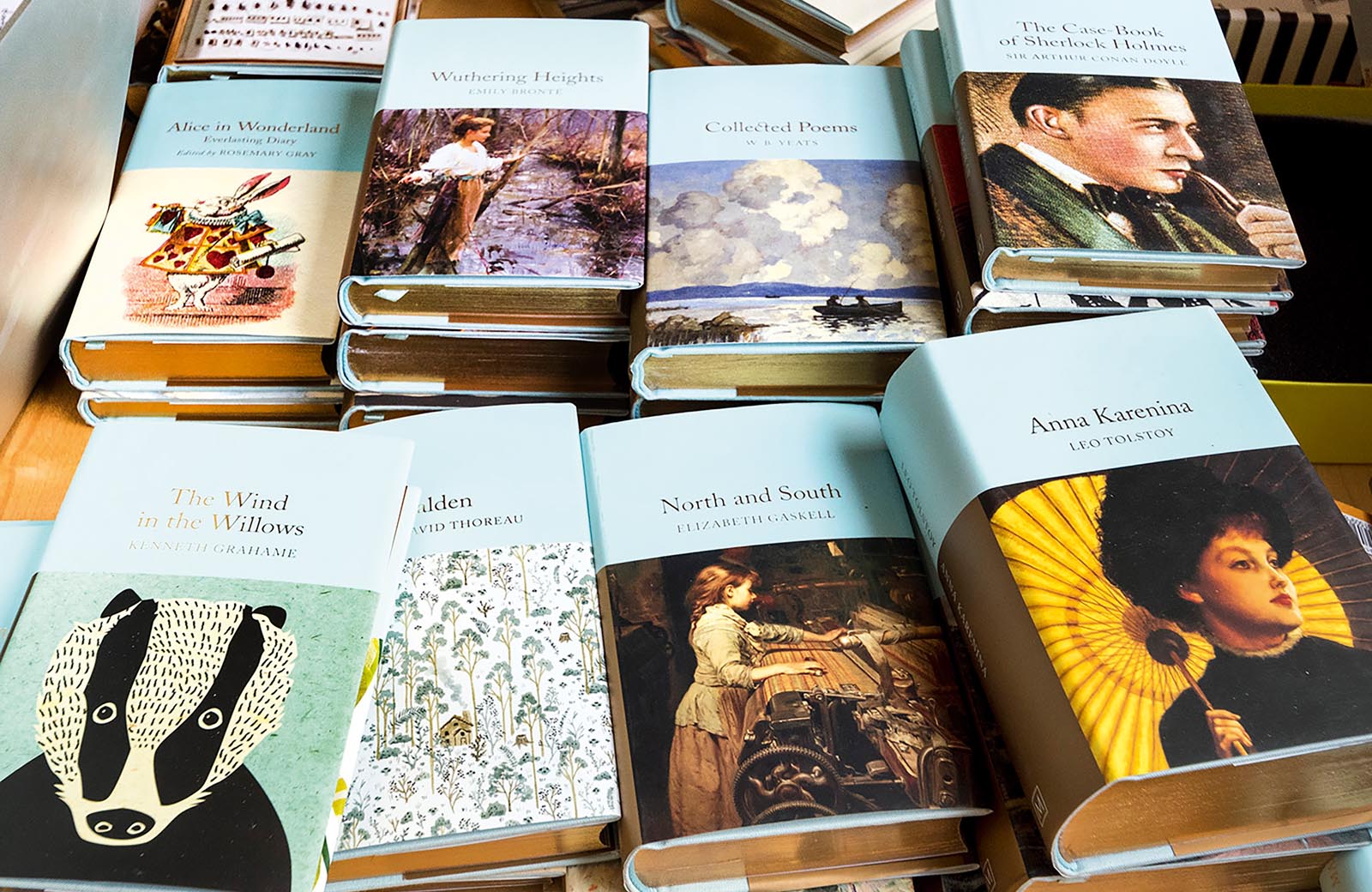

We make choices about whether to keep a copy of Wuthering Heights or a biography of Winston Churchill, to give away that book about dog breeds that Aunt Alice gave us, or whether to buy a first edition of a beloved classic. These are acts of conscious choice and also acts of creative expression.

When we decide to keep a book and make space for it on our shelves, it becomes more than just a book. It becomes a placeholder, a breadcrumb, an invitation that we can return to at any time. Perhaps to re-read it; or just to think about it for a moment as we pass by; or to respond to a guest who notices it and says, “I didn’t know you were interested in philosophy.” Walk into a stranger’s home anywhere in the world—want to know something about them or what to talk about over dinner? Simply look at their bookshelves.

Credit: Joe Tighe.

When we merge our books with a partner’s and perhaps add children to the house, our bookshelves and libraries take on new meaning, serving to tell the story not just of one life and where we have been, but that of the entire family and our future.

We could choose to keep other things on our shelves—and many times we do—but nothing tells the story of who we are, where we have been, and where we are going like our books.

The books we keep reveal a story that is never-ending, it can constantly be rewritten, edited, and have chapters added, simply by changing the books on the shelf. Whether the books are in our hands or on our shelves, their covers open or shut, they keep on telling stories. And so should we.

So long as there are words on a page they will tell a story. And so long as there are printed books on the shelf they will tell a story. The books we keep are the stories we tell.

Today, we thankfully have few, if any, limits on the books we read. Seemingly limitless books are available to us with one click. Within a few hours or days, a printed book is in our possession and anyone can have a library of hundreds or thousands of books in their home at a reasonable cost.

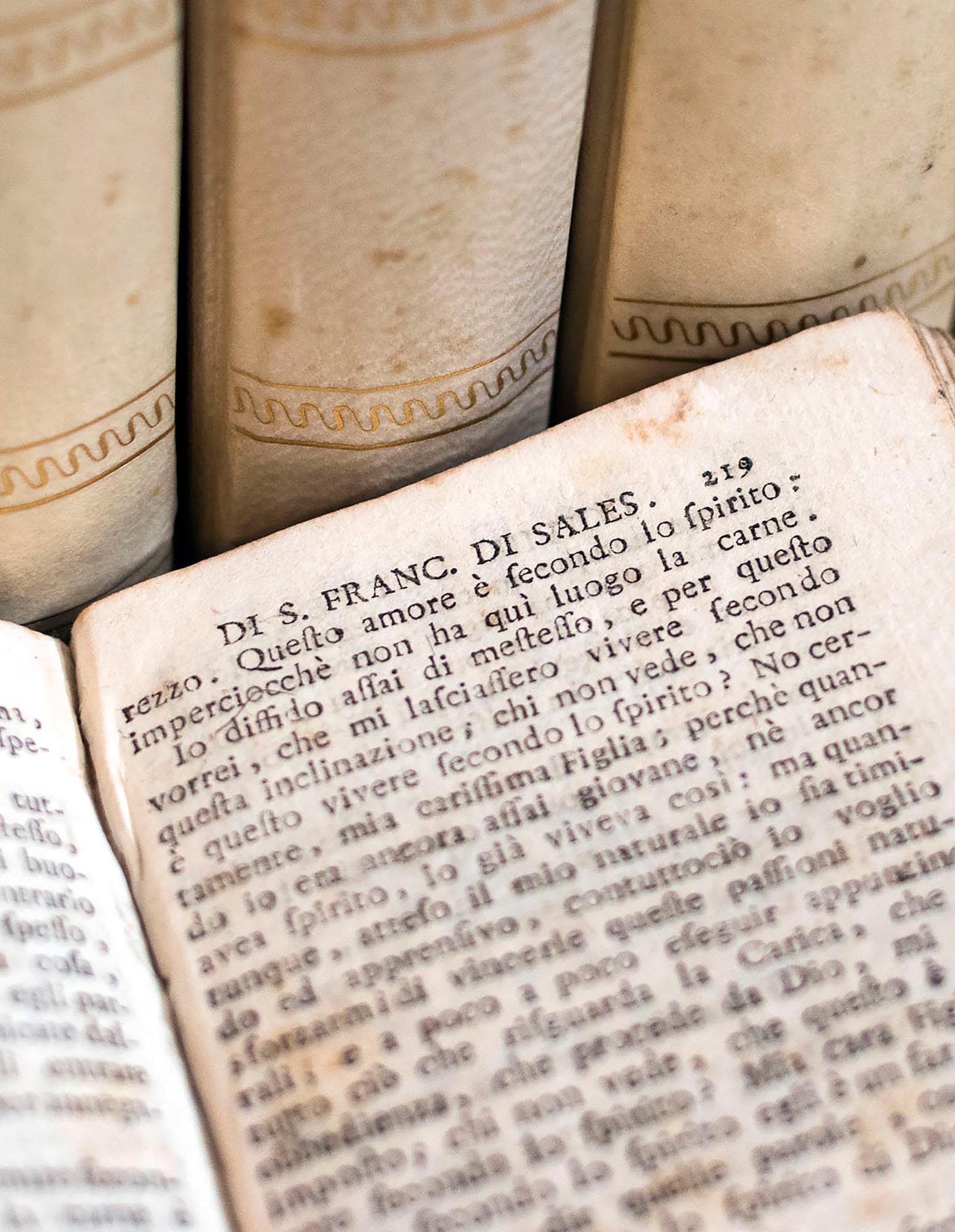

However, it has not always been this way. The earliest books took the form of clay tablets, then papyrus scrolls, and later parchment. They were hand copied before the invention of the printing press in the 1400s. When books were collected and stored in one place, they were largely a tool for control in service of a localized and defined power—either mortal or divine or both.

In Asia, where printing technology began, this technology was used not only as a means to spread information, but as a spiritual exercise for the divine—such as copying religious materials to gain merit with the Buddha.

The finest example of this practice is found in the text The Diamond Sutra, the earliest surviving printed book. The Diamond Sutra is a compilation of Buddhist teachings block-printed on seven sheets of paper and glued together into a scroll sixteen feet long. A colophon at the end of the document states its purpose—that Wang Jie had the scroll “reverently made for universal distribution . . . on behalf of his two parents” on May 11, 868.2 The Diamond Sutra is a certain triumph of this earliest printing technology.

Along similar lines, in 1900, a chamber within a cave was discovered that had been sealed up more than one thousand years ago. Located outside of the town of Dunhuang, at the Gobi Desert’s border in western China, the chamber contained more than five hundred cubic feet of collected manuscripts. Now referred to as the Dunhuang Library, the texts within remained inaccessible for more than nine hundred years.3

What was the intent behind sealing the chamber? Were these manuscripts trapped in the cave as an offering to a deity? It’s very likely. In the early Middle Ages, Dunhuang flourished as a site of government and as a popular center for Buddhist worship. Pilgrims traveled far to visit their cave shrines—hundreds of lavishly decorated caverns carved into the cliff. It is likely then, similar to The Diamond Sutra, that the texts in the Dunhuang Library were collected as a divine spiritual exercise, an offering to and acknowledgment of the power of the divine.

The collection of manuscripts in the cave tells a story, though its precise meaning is mysterious to us a millennium after the collection’s creation and placement. What is clear, however, is that a collection of manuscripts tells a different story than a single manuscript. For the most part, one manuscript would tell the story revealed on its pages. A collection of manuscripts, on the other hand, has the potential to reveal truths about the community and its power structure, their religious practices, and their communication methods.

Standing in contrast to Dunhuang is the Library of Alexandria, recognized as the earliest known library. King Ptolemy I Soter commissioned Demetrius of Phaleron to execute his plan in the third century BCE with the following vision: To create the world’s greatest library in service to the study of the natural world and the heavens above,4 housed within the Mouseion—the sacred temple of the Ptolemies dedicated to the Muses.

The library sought to store every piece of writing that passed through the port, and toward this aim, leadership got creative. As one story describes,

Ptolemy III Euergetes, or “Benefactor,” the third of his line to take the Alexandrian throne, was determined to be as beneficent as possible to the Mouseion’s library, no matter the cost. Having borrowed a number of classic works from Athens in exchange for a hefty deposit—fifteen talents of silver, totaling around more than 850 pounds in weight—he had the Mouseion’s scribes copy the originals before sending the new versions back to the shocked Athenians. . . . The Athenians kept the silver, and the Mouseion kept the books.” 5

This story shows clear execution of the belief that knowledge is power—the civilization that holds the texts (the knowledge), holds the power. Furthermore, power can be expanded by developing new methods (and larger places) to store knowledge for future applications by the forces in control (government).

The story of Alexandria is one that fascinates us to this day. The exact date of the destruction of the library and its priceless contents (estimates range from 40,000 to 400,000 manuscripts) is unknown. But we do know this: the Library of Alexandria had a reputation throughout the ancient world as a center of knowledge and learning, and this was a brand new story for the time.

Today we have libraries and universities circling the globe, they occasionally compete for the same rare books and papers for their archives. They also try to outdo each other in the quantity of their books and the quality of their architecture. The Library of Alexandria ushered in the era of the library as a source of power and influence that continues to this day.

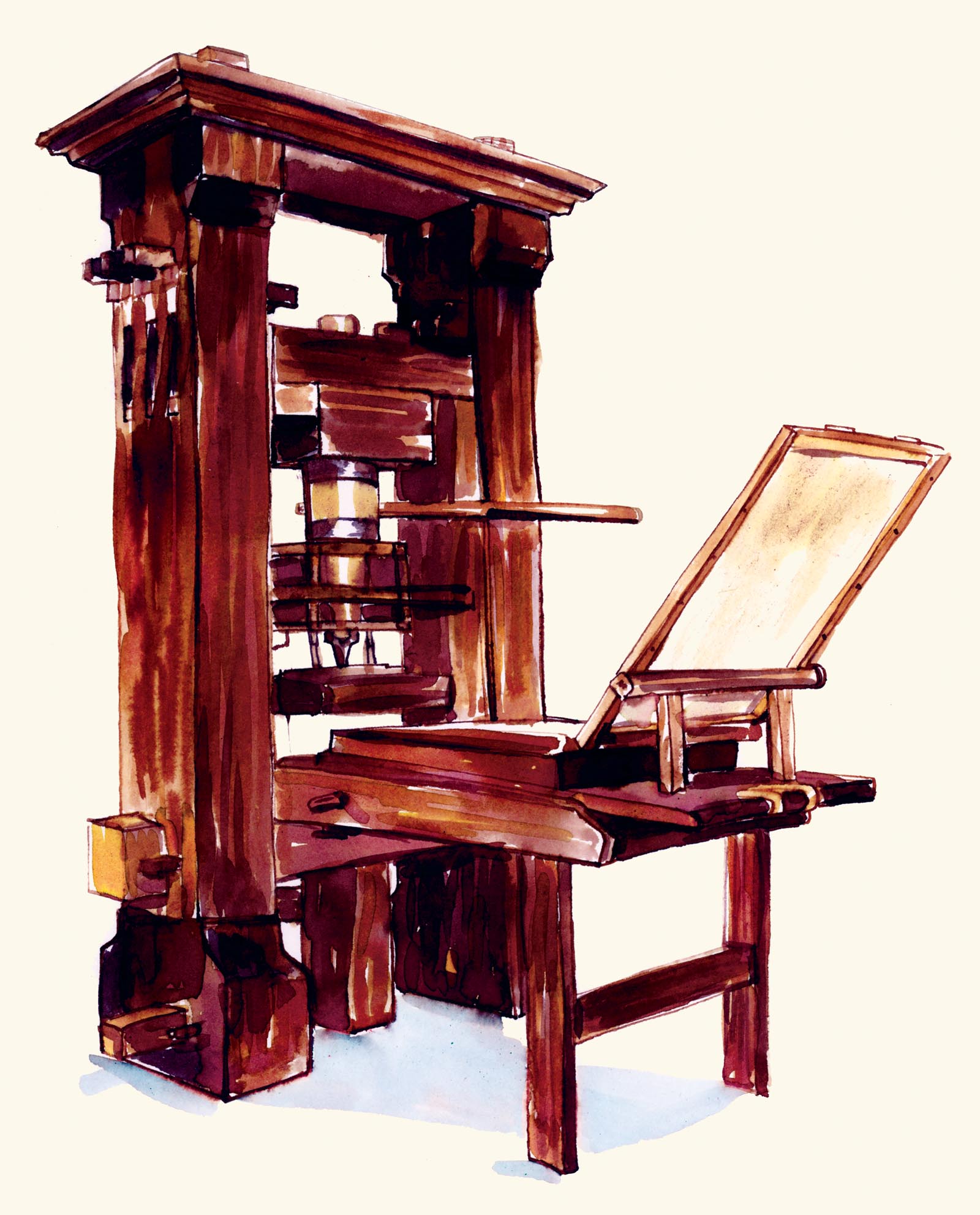

In the fifteenth century (around 1450 CE), Johannes Gutenberg invented the functional printing press, making what was once a laborious handmade task delegated to scribes into a mechanized revolution. By the century’s close, printing had spread to no less than 236 countries in Europe, with more than twenty million books produced. In 1455, all of Europe’s printed books could have been carried in a single wagon. Fifty years later, the number of book titles printed ran into tens of thousands, the total quantity of books printed was in the millions.6

With mass printing that Gutenberg’s printing press allowed, it became possible for the everyday person to more readily acquire books, making the elite luxury of a personal library an increasingly democratic possibility. As books became more accessible, ideas circulated with greater ease. With knowledge, the locus of power became dispersed, causing a shift that, as expected, created discomfort.

With books flooding the market in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, those in this new printing profession were regarded with deep suspicion as it was hard to reconcile the new technology with the deep-seeded belief that books were elite and rare in their very nature. What could books in quantities of the hundreds and thousands mean? A dangerous political agenda? A supernatural act? Rumor holds that when Johann Fust, Gutenberg’s ex-partner, went to Paris with cases full of books to sell, he was forced to flee, accused of being sent to do the devil’s work.7

The story of printed books and the power they give individuals to tell their own story through the books they keep really starts with Gutenberg and his invention. In the ensuing decades, books started to flow into people’s homes and with them flowed the power of storytelling. There was now unlimited potential to read something new and then become someone new.