The early 2000s witnessed the rise of e-books, smartphones, and tablets. With the advent of the e-reader in the twenty-first century people felt a new sense of freedom and excitement. This new technology seemed to solve countless problems. We no longer needed to lug around heavy books for travel or choose just one book to bring, limiting our choices. We were free to impulsively purchase whatever title crossed our path, no discernment necessary. If we noticed someone reading a book on the subway, with a click it could be ours too.

So we found ourselves, as the first decade of the new millennium came to a close, with the sales of printed books declining and e-books soaring. It seemed that the long, successful run of Gutenberg’s invention might be nearing the end of its useful life. From 2008 to 2012, e-book sales were rising quickly and were projected to surpass print book sales by 2017.

Credit: Joe Tighe.

The idea of holding a stack of paper with words printed on it seemed quaint in an era when you can get the same words from “the cloud” whenever and wherever you want. Why carry around heavy books when you can load thousands of titles onto your device with one touch, buying books as quickly as it takes to load a web page?

As adoption of the new technology grew and readers developed new routines for discovering, purchasing, and consuming books, many changes flowed through our culture. Bookstores closed en masse, libraries were redesigned to accommodate more technology and fewer books, and many publishers scaled back their releases and print runs.

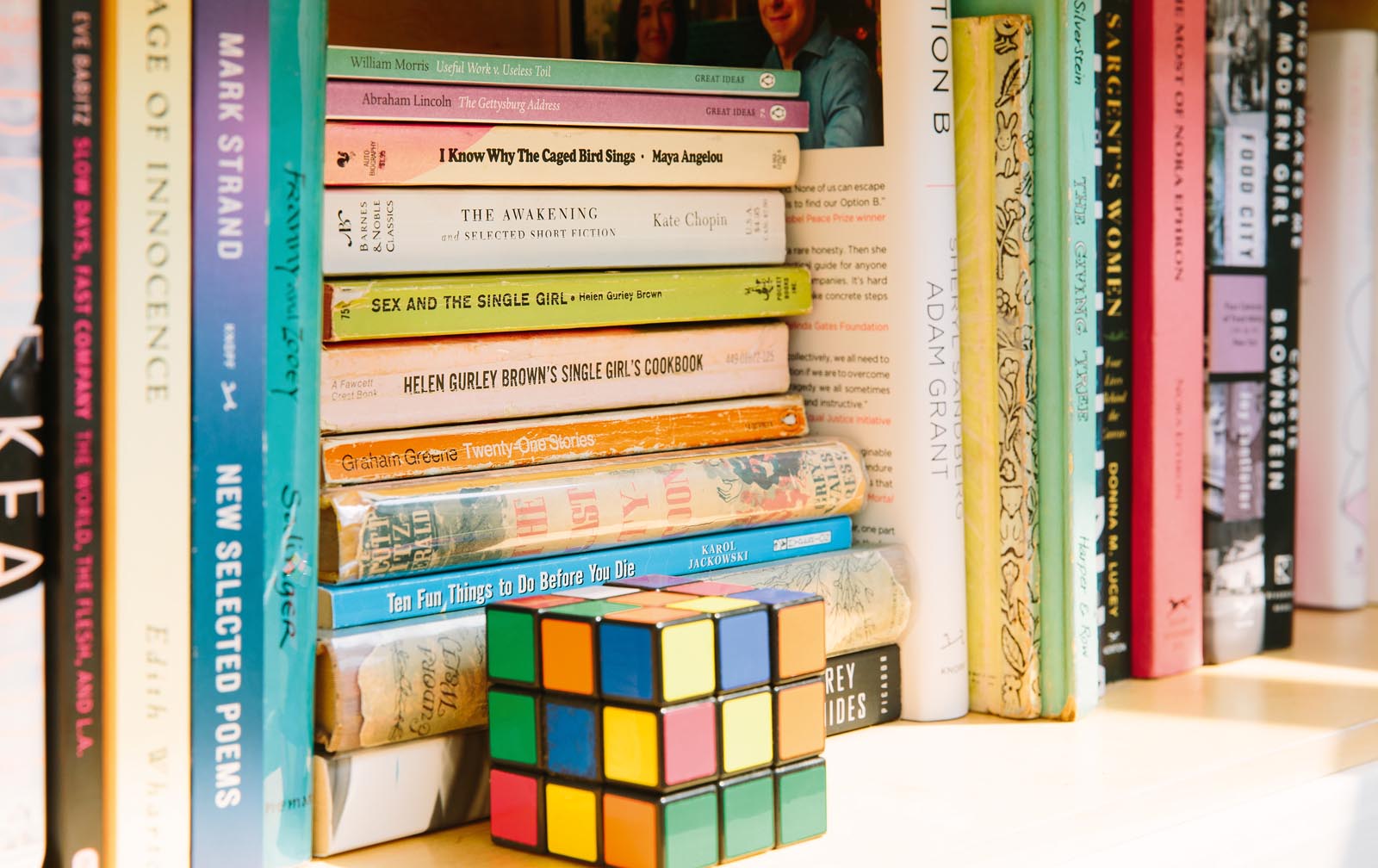

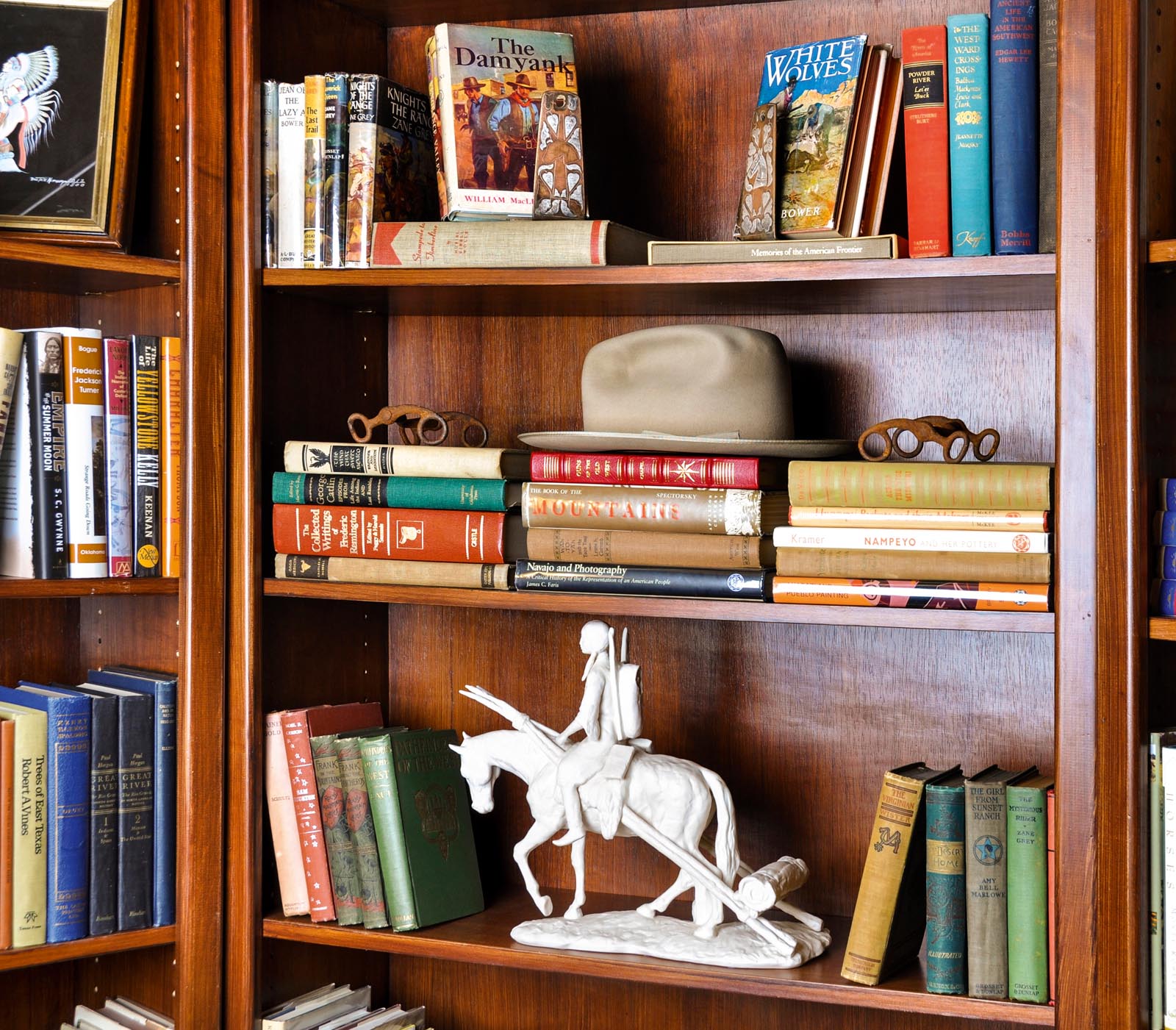

At the same time, lovers of the printed book were experiencing a certain sense of longing. The loss of the tactile connection with the book was certainly felt—the feel of the pages, the weight of the book in your hands, the smell of the paper—all essential to one’s experience and relationship with the story.

Credit: Christine Lane.

Alongside the loss of this essential physicality, there was a loss that was more subtle and less tangible—that sense of connection between the story, time, and place—each informed by where we were when we bought the book, who we were when we read it, and the ways that we were reintroduced every time we looked at or pulled a book from the shelf. There is an intrinsic relationship between story and memory that entwines and interacts with the narrative as the senses engage.

In 2008, Juniper Books had a major shift as Thatcher moved the business out of his basement and into a warehouse and studio space in Boulder, Colorado. From 2001 to 2008, the business had operated out of various basements, garages, and storage units. If the world was moving to e-books that took up no physical space, why was Juniper Books moving to a bigger commercial location with high ceilings and the capacity to do much more shipping and receiving than it had before?

Credit: Christine Han. Features the home of Christene Barberich.

Thatcher fielded numerous questions like this from his friends and family (and from the bank!). Was this the right time for business expansion? His friends in the technology business, where he had spent the first part of his career, thought he was crazy to be doubling down on analog. Who was buying or reading printed books anymore?

Architects and interior designers were now frequently designing houses entirely without bookshelves, believing that space for printed books was no longer needed. Clients wanted places to hang their flat screen TVs and they wanted shelves lined with electrical outlets to plug in their web-enabled photo frames, tablets, e-readers, and phones.

In resort communities like Beaver Creek, Colorado, designers told Thatcher that books looked “too small” in their large-scale homes. They wanted massive elk chandeliers and furniture made out of giant logs. Books looked out of place. Moreover, clients no longer traveled to their vacation homes with books in hand. They came with e-readers.

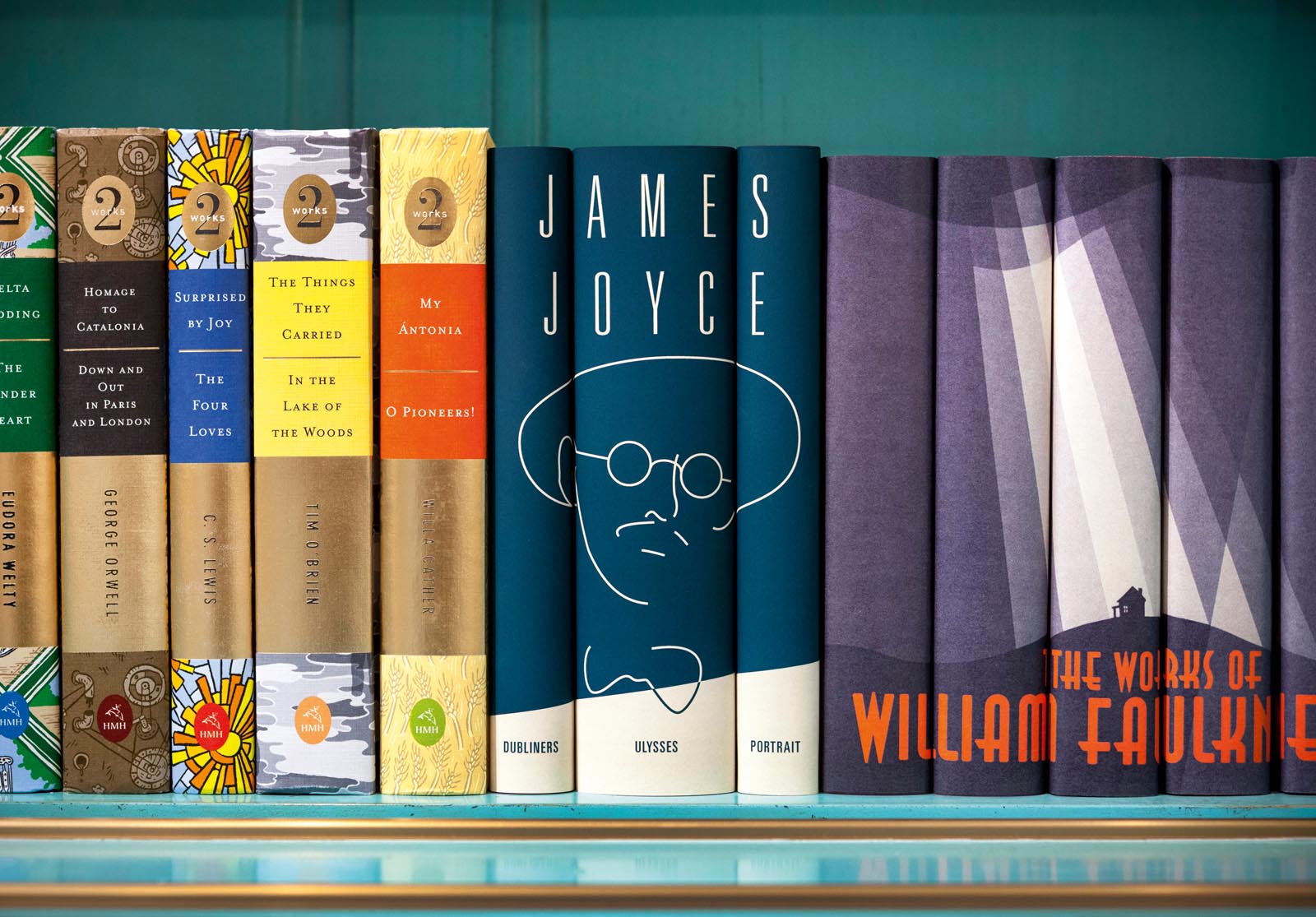

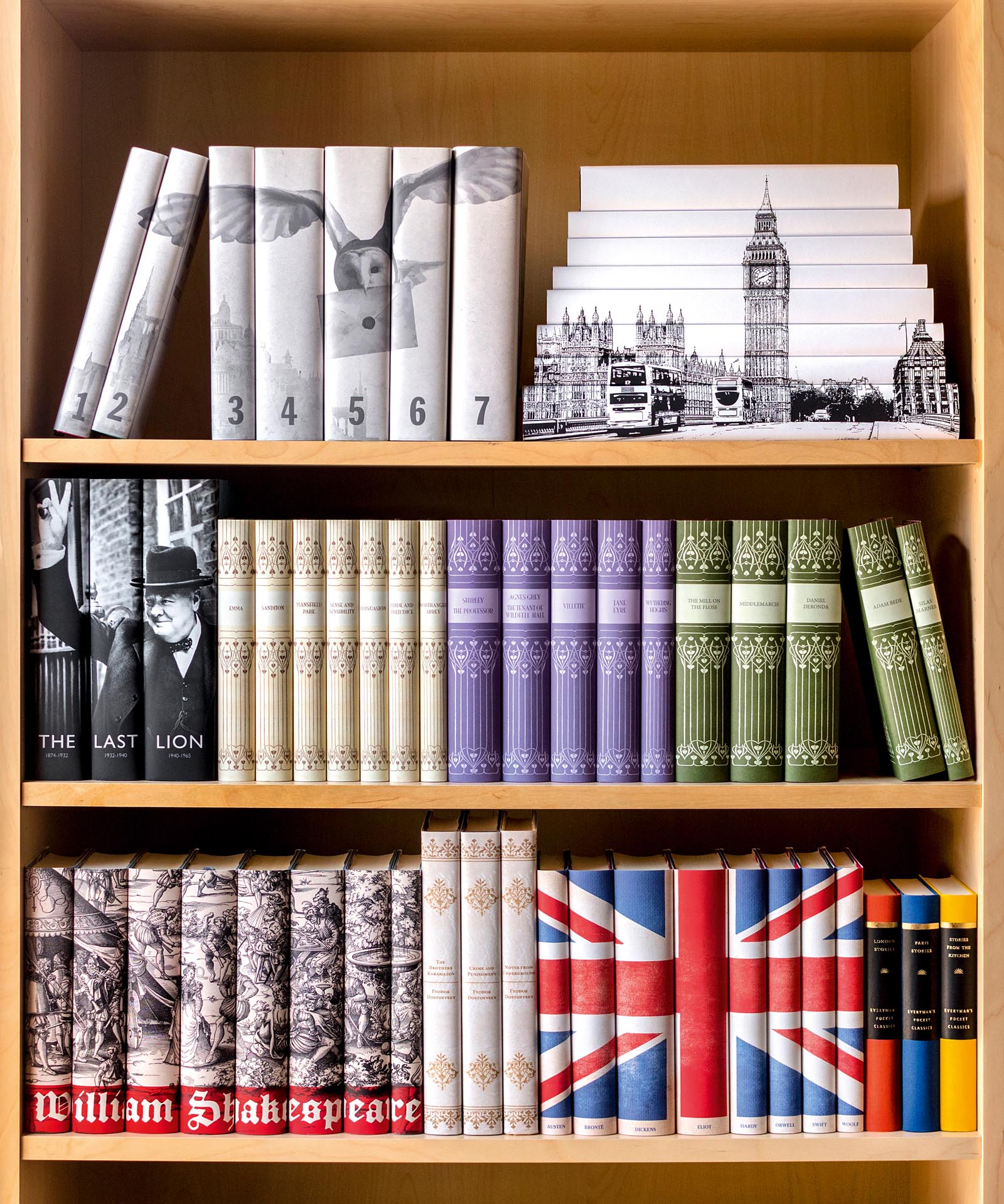

Yet, in the midst of the e-reader sensation, Thatcher sensed that true lovers of the printed book were becoming more dedicated than ever, and if he was hearing from even a few clients with nostalgia for print, then there must certainly be more out there. Thatcher also noticed that a certain demographic was approaching him with more frequency—clients in their fifties and sixties who had dreamed of building a library and retiring with free time to read their books. For these readers, a room of their own filled with printed books was a dream fulfilled.

As they reached this transition point in their lives, with empty nests and retirement within view, they envisioned a life filled with books, with reading. They could now read the classics that they didn’t have time to read while in the weeds, building their careers and raising their families.

Thatcher’s clients shared with him time and again that they didn’t work their whole lives—saving money, building their dream house, and their dream bookshelves—to reach this point and find out that printed books had become extinct, vanished like the dinosaurs. They wanted to fill their shelves with books while they still had time to enjoy them.

In the battle between printed books and e-books, Thatcher realized that printed books would always be loved and cherished by those who appreciated holding books in their hands and seeing them on their shelves. The rise of the e-reader did not signal the demise of the printed book, rather it stimulated a newfound appreciation for a five-centuries-old technology that perhaps we had come to take for granted.

It was at this time, while at the crossroads contemplating the future of print in our culture and society, that Thatcher came to better understand the role that books play in the lives of individuals. While e-books are entertaining and convenient, they cannot replace all of the functions that printed books provide.

Juniper Books was not just selling books; it was helping clients understand and make sense of their lives, offering the opportunity to reclaim some space and time for themselves amid all the demands of modern society. Books are so much more than the plotlines mapped out on the pages, they are a way to understand the essence of who we are and then present that vision to the world on our shelves and in our homes.

With respect to space and time, books are like a wall of resistance against a world that demands everything we have to give.

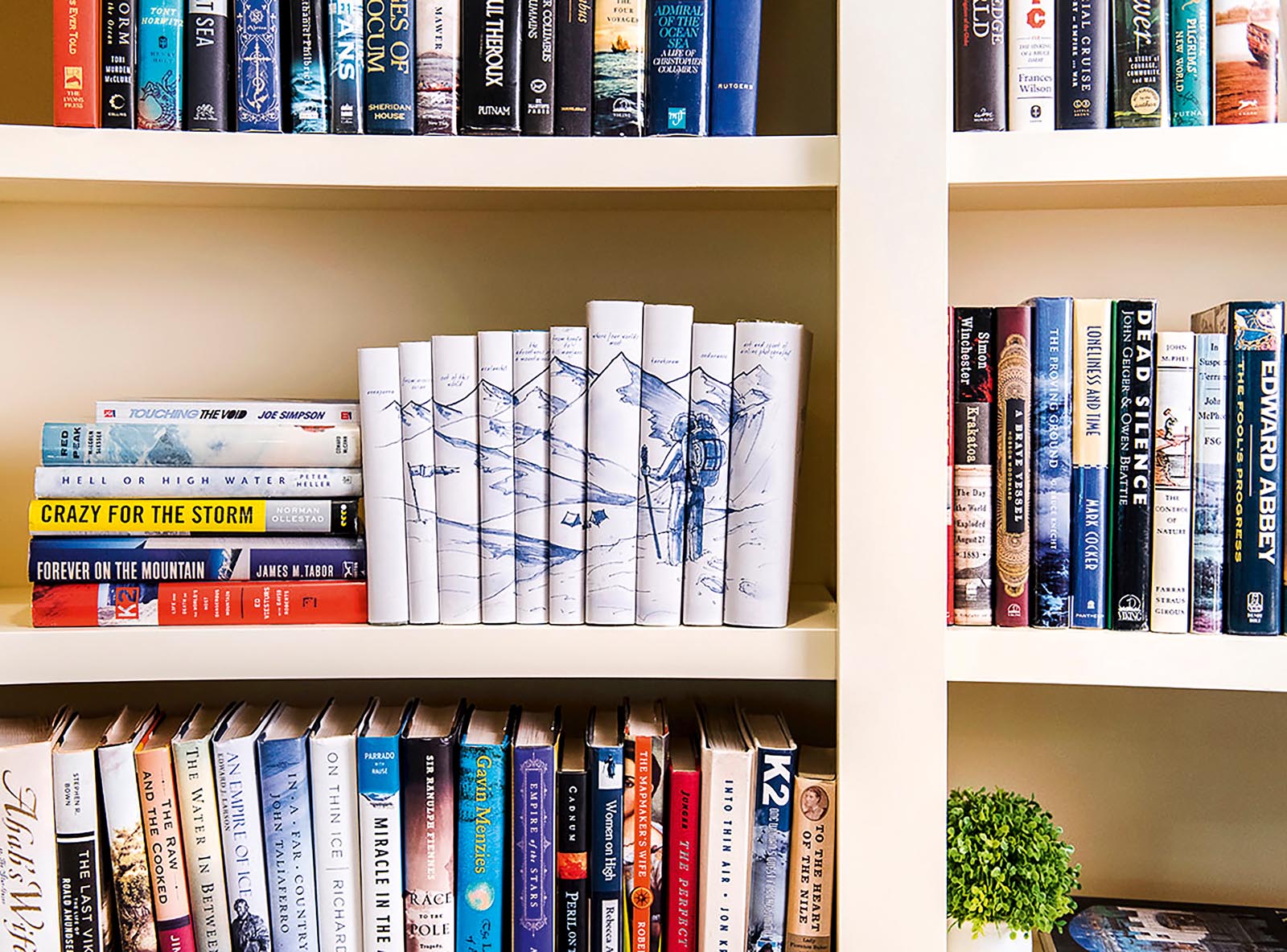

Reading a book allows you to travel through space and time to other places, to see the world from other perspectives, and walk in another’s shoes for a bit. Stories create possibilities for our limited vantages to be cracked open, affording new views and different experiences.

Reading forces us to slow down. In the fast-paced world we live, time is accelerating and we feel we have less of it. Our focus shifts second by second. We flip through our friends’ updates on social media quickly to get the story. We get impatient when a song or a movie takes too long to download. We read on our devices, take a pause and check our email, check our texts. Our concentration is spent in bursts and the sense of chaos builds.

And we are in a time of chaos. Each one of us can feel it. The pressure and the speed often feel relentless.

Who has time to read a book? That takes hours.

Who has time to write a book? That takes years.

And yet an author spent years writing every one of the books on our shelves.

We can feel the sense of time that a collection of books represents whether we know it consciously or not. We could look at our books and feel overwhelmed.

A sense of frustration with ourselves and our lives might creep in if we believe we don’t have time to read any or all of our books.

But mostly we’ve found that books bring a sense of peace, calm, and quiet to a home. We know at some level that time spent with a book is exactly what we need.

When we look up from our phones at our bookshelves, we’re reminded that we once had the time to spend ten or twenty hours with every one of those books. We know that before life became impossibly busy, we had more time to spend reading what we wanted to read. Perhaps then our books become a placeholder for the time we wish we had and hope we might have again one day.

Perhaps just a short time ago, reading a book was a part of your natural rhythm, an inclination to find the quiet within the chaos. When you had a few minutes to spare, you turned to a book. We yearn for this core sense of peace because we viscerally recognize it. And we have the freedom to claim it, to lean into the quiet and pick up a book. To claim this—to slow down and settle in with a story—this becomes a radical act of self-care. Reading is self-care.

As human beings living in a digital age, time-starved and rushing around, printed books are reminders of the time we once had, the time we want to have, and the time we hope to have. Printed books quell the chaos. Printed books make us feel comfortable and make us feel like everything is going to be OK.

Credit: Christine Han. Features the home of Claudia Wu.

What comes to mind when you think about that book? Is it the plot? A character? Or is it something about the book’s relationship to you? If you thought of your favorite Jane Austen or Ernest Hemingway novel, perhaps what came to mind was a feeling of holding the book in your hands, a sense of where on the pages a favorite scene or passage was printed, or a memory of whom you were dating at the time.

Now compare this to e-books. If you have read an e-book recently, think of your favorite book or just one that you consumed on your device via the cloud. It’s a little different. Do you recall where you were when you read that book? How the device felt in your hands as you scrolled through the “pages”? Do you picture where in your list of downloads that book is? Maybe it’s after the Malcolm Gladwell and before that scandalous romance novel you downloaded while on vacation—the one that you are relieved lives anonymously in the cloud rather than in physical form.

The iPhone hit the market in 2006. Steve Jobs introduced a device that was big enough to display “detailed, legible graphics, but small enough to fit comfortably in the hand and pocket.” This device became the world’s best-selling smartphone, changing the way we as a culture interact with our “devices” and, more significantly, with each other.

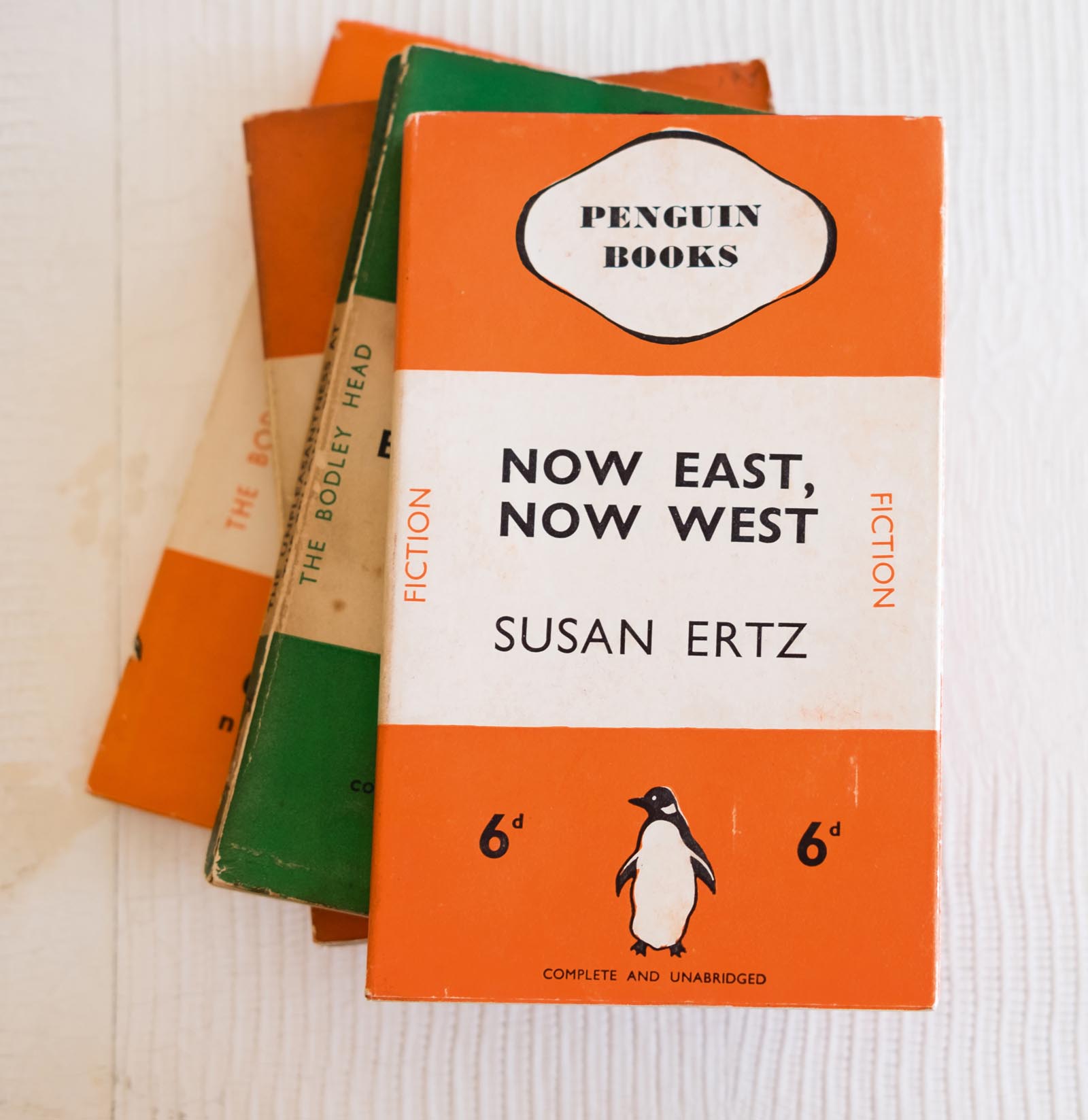

Seventy-five years ago, in a narrative that seems to foreshadow the dawn of the smartphone and e-reader, two innovators—Allen Lane in England and Robert de Graff in America—had a similar epiphany: they could change the reading habits of an entire culture just by making books smaller and more disposable, simultaneously changing the way we read and the way we perceive books.

In the 1930s, it was difficult for ordinary Americans to get their hands on good books. The country had only five hundred bookstores nationwide (in contrast there are approximately 2,200 independent bookstores today, not counting online retailers like Amazon), all clustered in the biggest twelve cities. There was also a significant monetary barrier as hardcovers cost $2.50 (equivalent to about $45 today). In response to this barrier to access, Allen Lane founded Penguin Books and Robert de Graff founded Pocket Books, bringing their idea of smaller, cheaper books to market.

This wasn’t the first time books were covered in paper. In a sense, “paperbacks” are almost as old as moveable type. Historians trace the first paperback books to Aldus Manutius, a Venetian printer and publisher. At the start of the twentieth century, the French publishing houses primarily published in paperback (the first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, published in Paris in 1922, is a paperback) and dime novels, or “penny dreadfuls”—lurid romances that were considered trashy by respectable houses, were sold in Britain before Penguin Books. Allen Lane’s idea, though, was a bit different.

According to Penguin lore, Lane’s eureka moment happened as follows:

He just wanted a decent book to read. . . . Not too much to ask is it? It was in 1935 that Allen Lane, Managing Director of Bodley Head Publishers, stood on a platform at Exeter railway station looking for something good to read on his journey back to London. His choice was limited to popular magazines and poor-quality paperbacks—the same choice faced every day by the vast majority of readers, few of whom could afford hardbacks. . . . Lane’s disappointment and subsequent anger at the range of books generally available led him to found a company—and change the world . . . the quality paperback had arrived.1

Lane knew that if he provided intelligent books for a low price, the reading community would grow profoundly. Supply the books and the readers will follow. And so, in the summer of 1935, Lane launched Penguin Books with ten titles, including his friend Ms. Christie’s novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

Robert de Graff, perhaps believing even more than Lane in the democratization of literature, launched Pocket Books in May 1939. With his prototype, a pocket-sized book measuring four-by-six inches and priced at a quarter, de Graff further pushed the needle in the book market by making books more accessible with respect to size and price, exploding the potential on not only who would read, but where they would read.

As if overnight, it seemed that the public had a book in hand, similar to how we check our email or update our social media, our browsing no longer constrained by the cumbersome laptop. In continued contrast to Lane, de Graff wasn’t concerned with the quality of literature. Instead he focused on mysteries and romances, the racier the better. Disrupting the book industry even further, de Graff worked with magazine distributors to place his books beyond the bookstore into grocery stores, drugstores, and airports. Within two years he’d sold seventeen million copies.2

The impact of the paperback was twofold. With their vast popularity, these little, inexpensive books put pressure on the hardcover publishing houses, which in turn put pressure on the legal regulation of print. There wasn’t much regulation on books for paperback release, and so the more salacious story was often preferred. This resulted in a wider range of stories that would be considered fit to print in both hardcover and paperback ushering in a culture shift. The stories published in 1945 were vastly different than those published just twenty years later. As Louis Menand reflects in The New Yorker, without pulp paperbacks, there may not have been a Philip Roth or an Erica Jong.3

One story about Thatcher’s beloved maroon-covered copy of The Catcher in the Rye fits well into this discussion. For the early paperback covers, the cover designs tended to go after readers in the same way movie posters did at the time, playing up the more risqué features, even if they were wholly tangential to the storyline. When The Catcher in the Rye was published in hardcover by Little, Brown, in 1951, sales were solid, but it was not the hit it would become. For the paperback treatment, Salinger did not want his book to have the typical pulp cover. Yet, in spite of Salinger’s request, the Signet edition came out in 1953 with the cover illustrated by “the Rembrandt of Pulp,” James Avati. Avati’s cover shows Holden Caulfield standing outside what appears to be a Times Square strip club, the front cover blurb stating, “This unusual book may shock you, will make you laugh, and may break your heart—but you will never forget it!”4 He clearly gave the public what they wanted. By 1954, the paperback had sold 1.25 million copies. Even so, Salinger was furious. When the paperback rights to The Catcher in the Rye became available again and Bantam Books won the deal, Salinger designed the all-text maroon cover himself, and also the simple geometric designs that characterize his later novels.5