Where do books come from?

On the one hand, that’s a simple question—they come from the mind of an author. They pass through the hands of an editor. A company publishes the book or at least provides a self-publishing service. A bookstore or online store then sells copies of the book to individuals who take the book home to read.

Books go from the mind of one person to the hands and minds of many readers. There is generally one story that the book tells and that story is repeated many times over as the book is read around the world, talked about in book groups, online reviews, and bookstores.

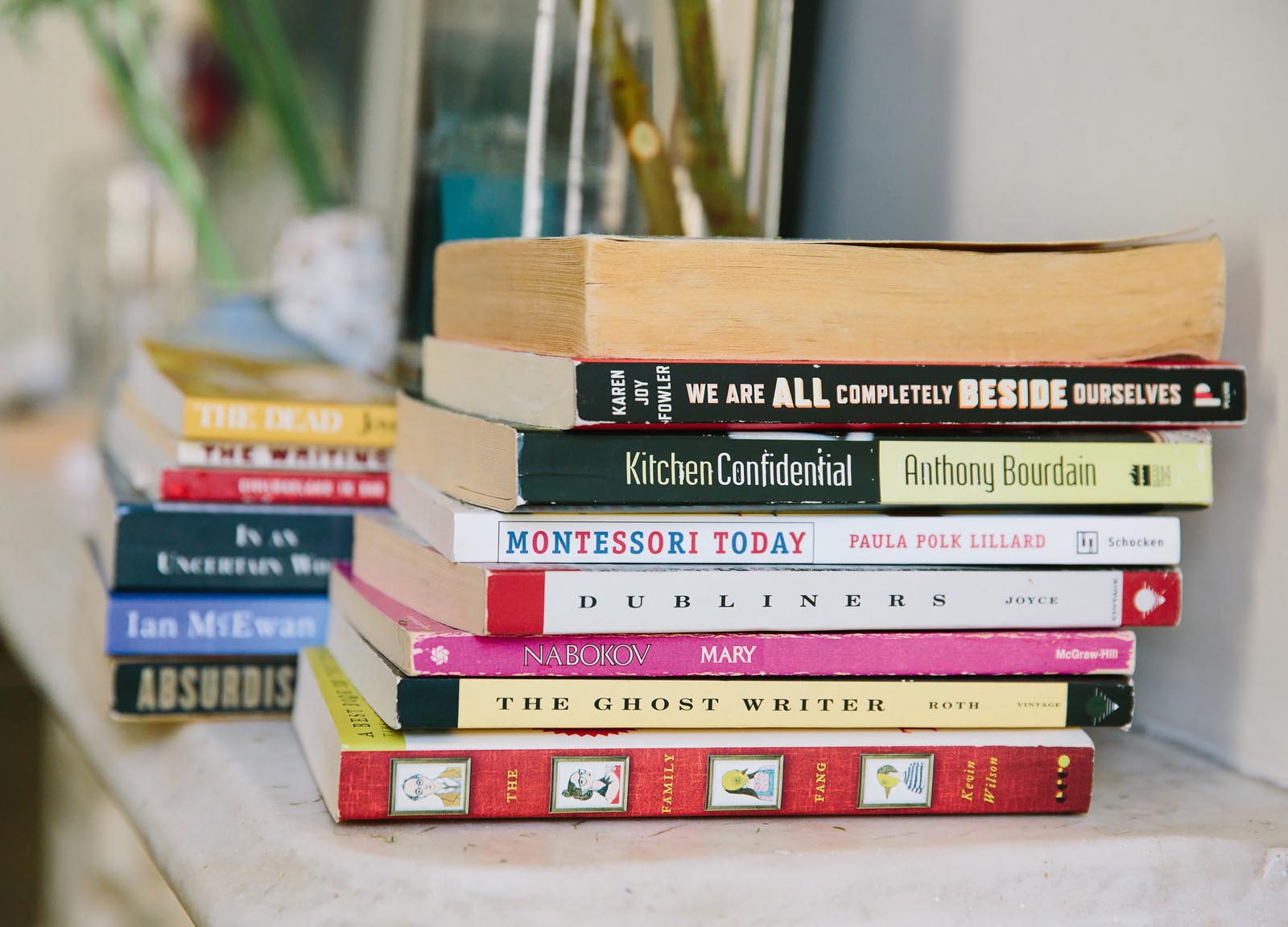

On the other hand, our bookshelves at home hold their own collection of stories. The murder mysteries, espionage thrillers, love stories—each one is a facet of the big story. Our shelves are not just the stories contained within the books but the stories of how those books came to be on our shelves.

Credit: Christine Han.

These days many people buy books on Amazon.com, while others patronize local bookstores for a more personal experience. There are countless ways for a book to wind up on our shelves including from library sales, thrift shops, or specialty retailers like Anthropologie. Each of us has probably received books as gifts, or maybe borrowed one from the library and never returned it!

Do we still have the books that our parents gave us or that our grandparents had? Books we bought for school, and then kept? Books we picked up in an airport, or while traveling and supporting a local bookstore?

What about those select books our friends or romantic interests gave us to make a point. “Read page thirteen and tell me that’s not us!” Where do those fit in?

Books that we bought because we wanted to read something in that moment, to be entertained.

Books we bought because we wanted to own those specific words on our shelves. That exact copy. Possession!

Perhaps you have a collection that didn’t seem complete without all the books by John Steinbeck or all the books about Paul Cézanne. Or all the books mentioned in 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die (a lot of books!).

The point is that some books magically appear in our lives, like the ones given to us as children. Others are more intentional. They are “collected.”

Almost everyone has a book collection whether they realize it or not. The books you read in school, the books you’ve been given by friends, the books you inherited from your parents or grandparents. There is a story in all of them. You can choose to tell this story in your present home, or to part ways with these books and tell a different story.

For those who have embarked on the journey to build their own book collection or a dream library with considered choices, there is a sincere intentionality to the process. There are also unlimited options that can feel overwhelming.

No matter how books enter our lives, we have a choice within any moment to decide what to do with them. We live in the material world, in buildings and houses. In most cases, we cannot keep unlimited amounts of stuff. We have to decide what is important to us and then decide where it goes.

Credit: Christine Han. Features the home of Helen Dealtry.

Books are unlike other household objects in that one can have a “collection of books” without being a “book collector.” There are very few objects that have so much versatility, that can be acquired at so little relative cost, and that function as decoration when not being used for entertainment or intellectual engagement.

The artwork on your walls serves as decoration, its purpose for visual enjoyment. You interact with your paintings by looking at them, you don’t also take the canvases down and paint on them as a hobby.

On the other hand, the cookware in your kitchen is for cooking and not for decoration. Those pretty copper pots are one exception of course, but generally you do not just look at your cookware, you use it to make something.

Books play so many roles in our homes and our lives. We can read them and be entertained and learn something. We can keep them on the shelves and smile when we look at them, reminded of the tales within and the story they tell of who we are.

We can show them off to houseguests without reading from their pages—“I bought this copy in Paris while in college,” or “This is a first edition I picked up at the town library sale.”

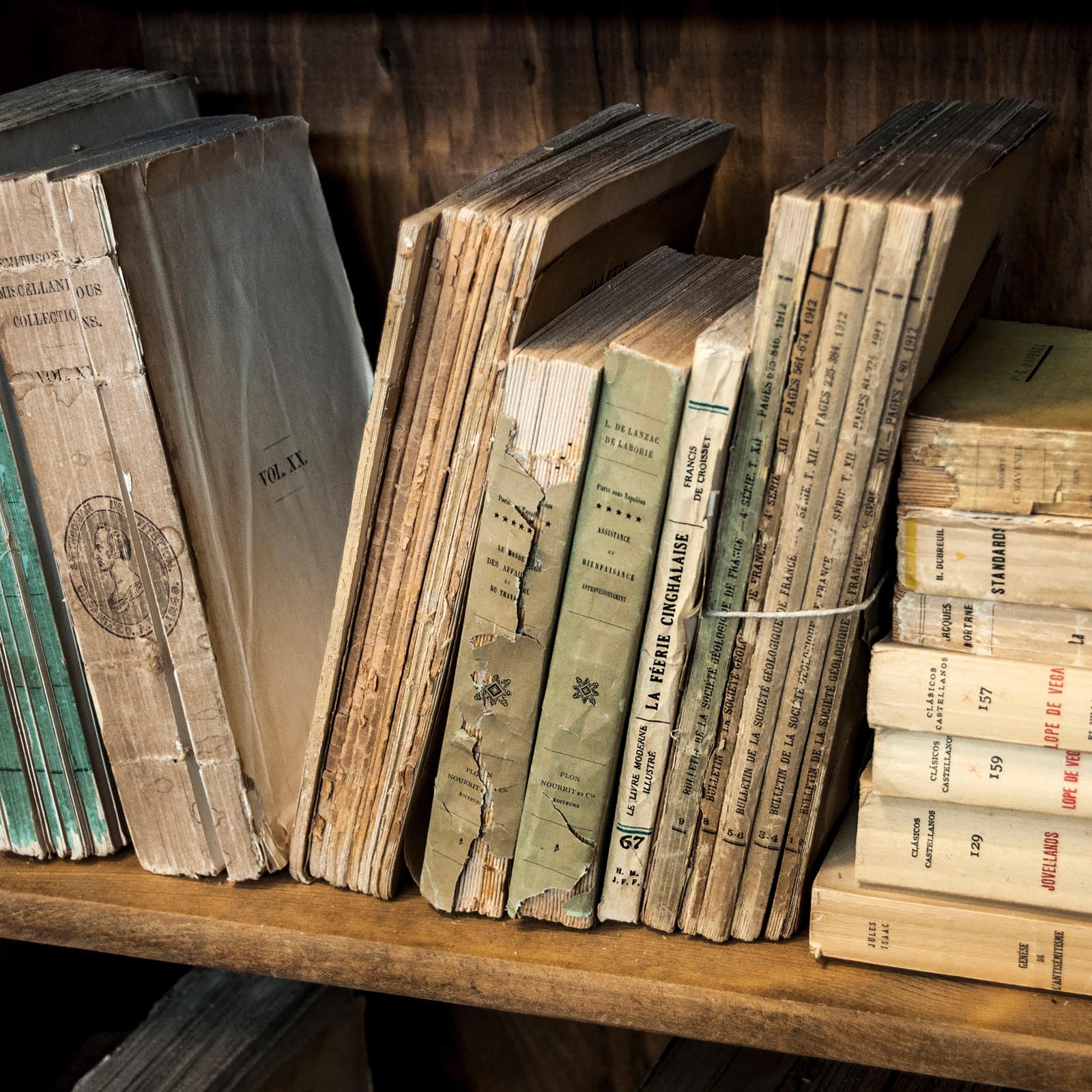

Credit: Christine Han. Features the home of Helen Dealtry.

There is nothing in our homes quite like a book. Wouldn’t it be great if we could keep unlimited amounts of them? Books in every room, piled high, yet organized in such a way that we knew where that exact title was, exactly when we wanted it.

Sadly the dream of infinite books is just a dream. Our space is limited and we can only keep so many books. That constraint forces choices. What if these choices and the decision-making that comes with them could be seen as a path to personal growth and understanding? We believe it is exactly that.

Just as the books we keep tell the story of who we are, the books we do not keep must be let go with an open heart and open mind. Letting a book go is an equally essential part of our ever unfolding story. We have to ask ourselves honestly, why do I have this book?

Credit: Christine Han.

Credit: Christine Lane.

Credit: Christine Han. Features the home of Helen Dealtry.

Are all of my books presently meaningful to me or is it time for some of them to go?

Do they reflect a past interest that is no longer “me”?

Do they hold secrets and sentimental attachments I still need to keep? For example the love poem inside the back cover of my college edition of Rilke.

Do I love the story within the book or this edition of the book? Is it time to upgrade my ratty paperback to a beautiful leather-bound edition?

Am I keeping this book because it’s too hard to sell or donate?

We’ve looked through our books; through this process we’ll unearth the one-offs and the collections. We’ll decide what books continue to tell our story and we’ll set aside those books that no longer do so. Yet, what happens when government or outside forces tell us what books to keep, determining which narratives will be a part of our story and which ones won’t, a true stake to our civil liberties and our selfhood?

Like VHS tapes and mood lamps, banning books is something we think of as a relic, but this is not the case. According to the American Booksellers for Free Expression (ABFE), the practice persists in the US and shows no signs of dwindling. Since 1990, the ABFE has been front and center in this fight for free speech, publishing a list of books challenged each year by American public libraries and schools, so that we may have the freedom to seek out and choose what we ultimately read.

In 2017, 416 books were challenged or banned, and among those most frequently named were Drama by Raina Telgemeier (a favorite of Elizabeth’s kids), The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini, George by Alex Gino, The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, and To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee.1

Thankfully, here in the US, there are still wide avenues to access books that are banned in certain school districts or parts of the world. We can seek out banned books, buy banned books, and read banned books with little to no fear of retribution. Though our kids may not have the freedom to read certain books in school, we can certainly find them for our homes and choose to have them on our shelves, a freedom easily taken for granted.

In Cuba, however, this is not the case. Books are highly controlled by the state and there is no broad margin to what Cuban citizens are allowed to read. There are no independent bookstores and foreign magazines are banned. Instead books are curated by the government and the only titles chosen are those that are in full support of those in power.2

There is a groundswell movement to counter this, and it’s been growing for more than twenty years. The “independent library” movement began in 1998 started by a man named Ramón Colás, to address the lack of idea exchange that this profound book banning ushered into his country, aiming to bring more diverse materials available to Cuban readers. The story follows thus:

Colás was at home watching television when Castro appeared on the screen, answering a journalist’s question about censorship: “There are no banned books in Cuba,” Castro declared. “Only those which we have no money to buy.”

Colas decided to put Castro’s words to the test. He and his wife, Berta Mexidor, opened the doors of their home and designated their collection of 800 books as an independent library, with no affiliation to Cuba’s state-run library system. They invited friends and neighbors to sit in their home and read or borrow any books of their choosing for free.

Soon independent libraries began popping up all over Cuba.

By 2001, there were 100 of them in private homes throughout the island. They stocked titles as diverse as One Hundred Years of Solitude, The Communist Manifesto, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and The Little Engine That Could.3

Building on the momentum created by Colás, a small literary underground network of private libraries have sprung up in rebellion to the repression over the past two decades and at great cost, with risk of raids from the government and arrest. But still these underground libraries grow, through swaps and flash sales, carrying the light of different viewpoints and creating bookshelves with a strong message for freedom of knowledge.

This continues to be a current issue. In April 2018, newly instated president Miguel Díaz-Canel signed a proposal for a new regulation, Decree 349, which limits artistic freedoms and supports institutional censorship within Cuba. The vague parameters of the decree essentially regulate any and all artistic and cultural activity within the Republic. Independent librarians and citizens continue to be met with intimidation, harassment, and repression by the government.4