We all know what a book is, but how do you define a “collection” or a “library”? For us, there isn’t an exact definition as books are personal to each individual and household. A collection may be two books, or it could be two thousand—what brings them together into a coherent collection is that they have a central theme.

A library could constitute perhaps one hundred books or thousands. Generally what unites a library is that all the books are in one place and a library can include a number of different collections within it. As we proceed through the next few chapters, we will discuss how you can have books for different purposes around your home, some combining to create collections, and even a library.

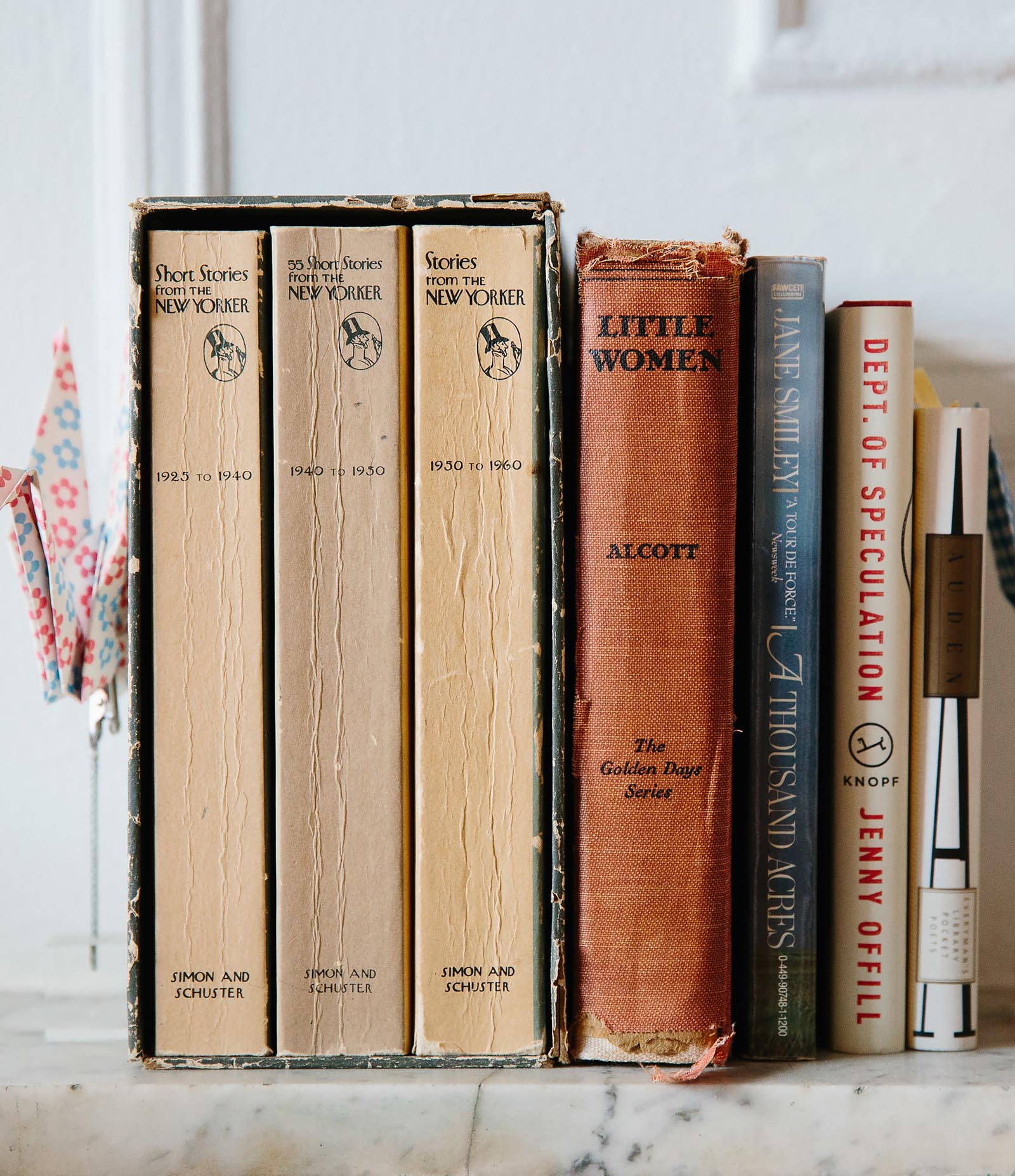

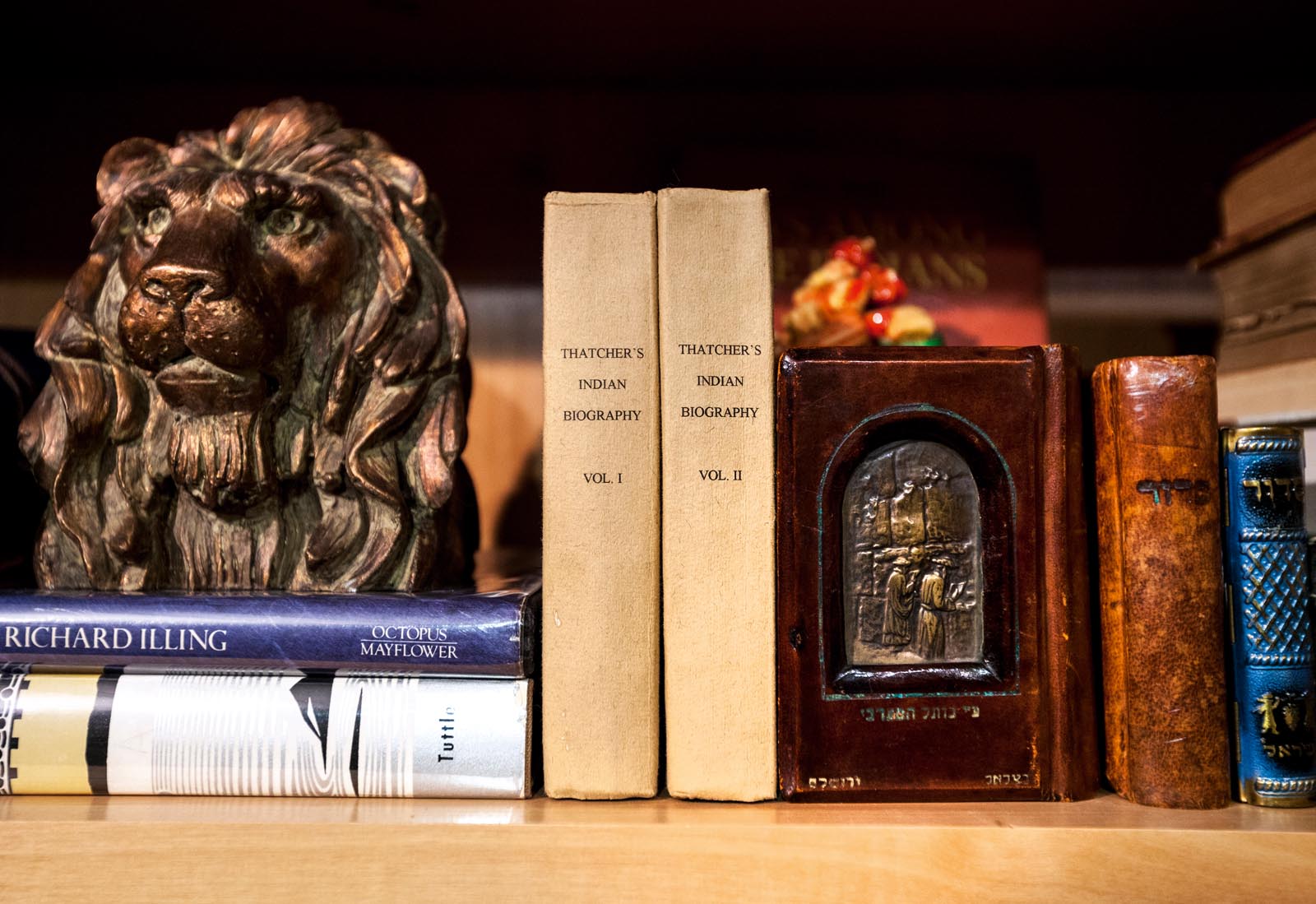

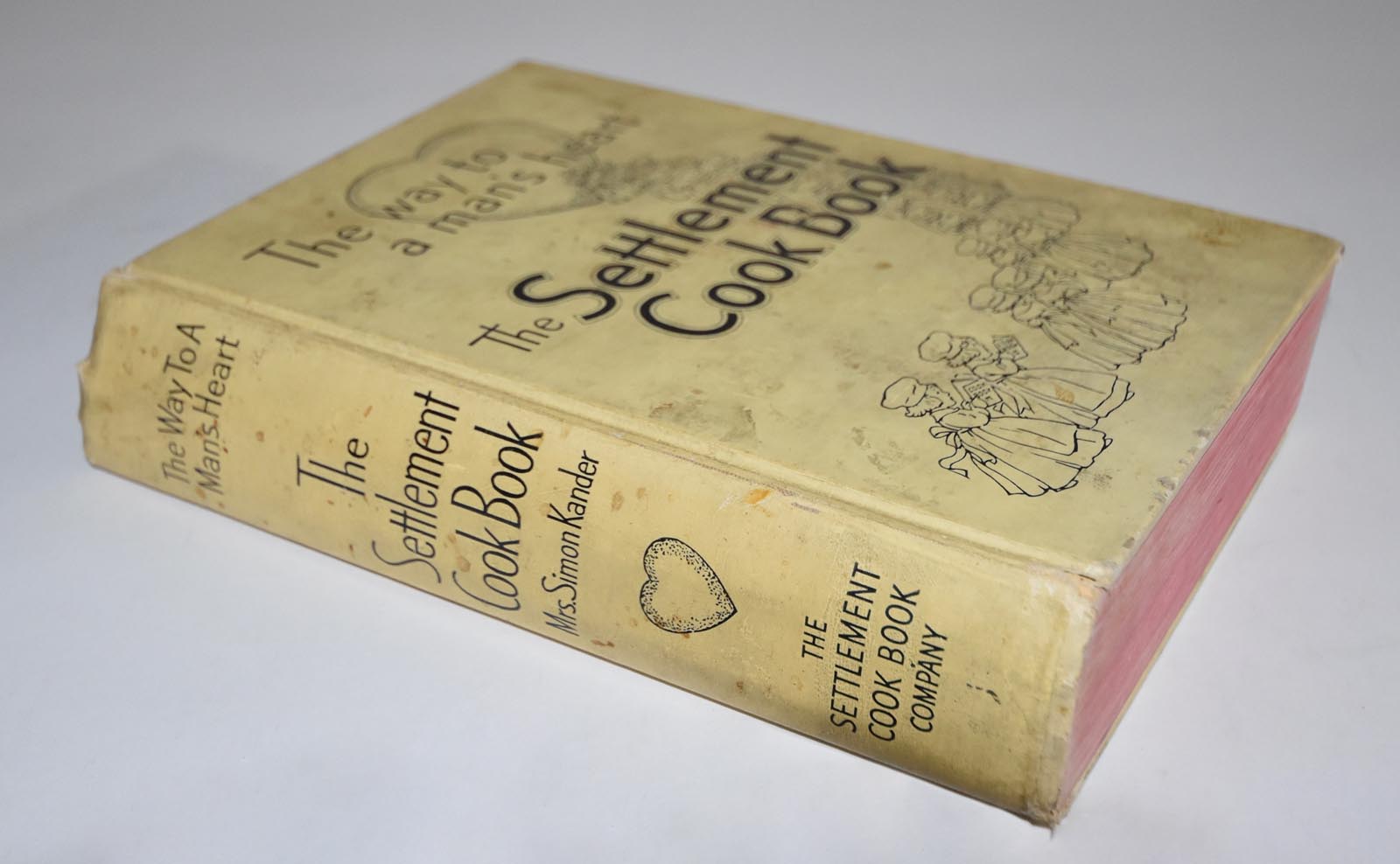

You can have a single book that doesn’t go with the others. For Thatcher, a good example might be his grandmother’s The Settlement Cook Book or his grandfather’s Hebrew prayer books.

They are sentimental books that represent a connection to the beloved grandparents who helped raise him. Does he read the books? Not really, but having them reminds him of his love for his family and their love for their books.

The subtitle of The Settlement Cook Book—The Way to a Man’s Heart—is sexist and outdated. Thatcher loves to cook and his father was a celebrated chef; they both find the subtitle amusing and so keeping the book also becomes a reminder of generational and societal change.

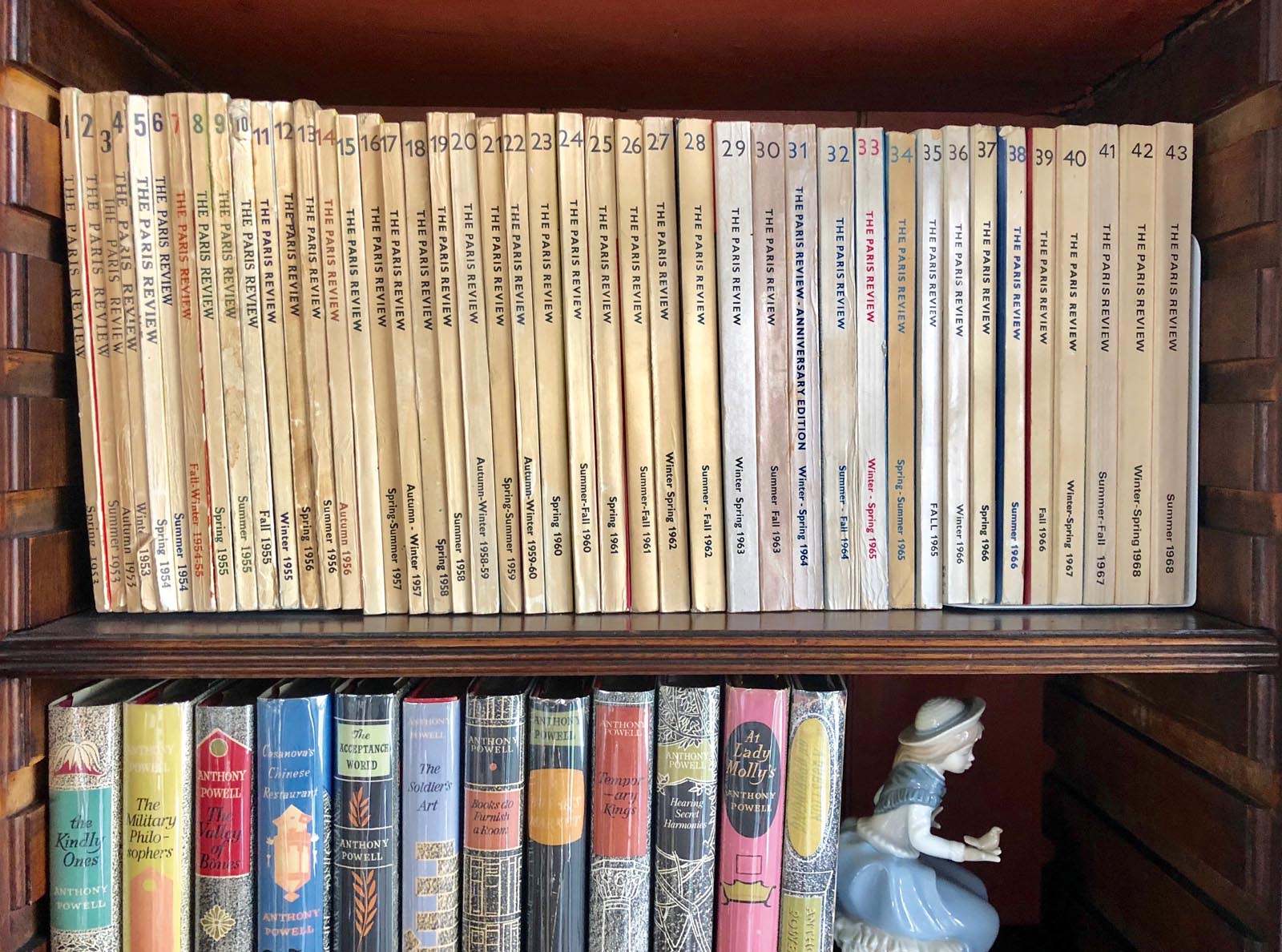

Credit: Christine Han.

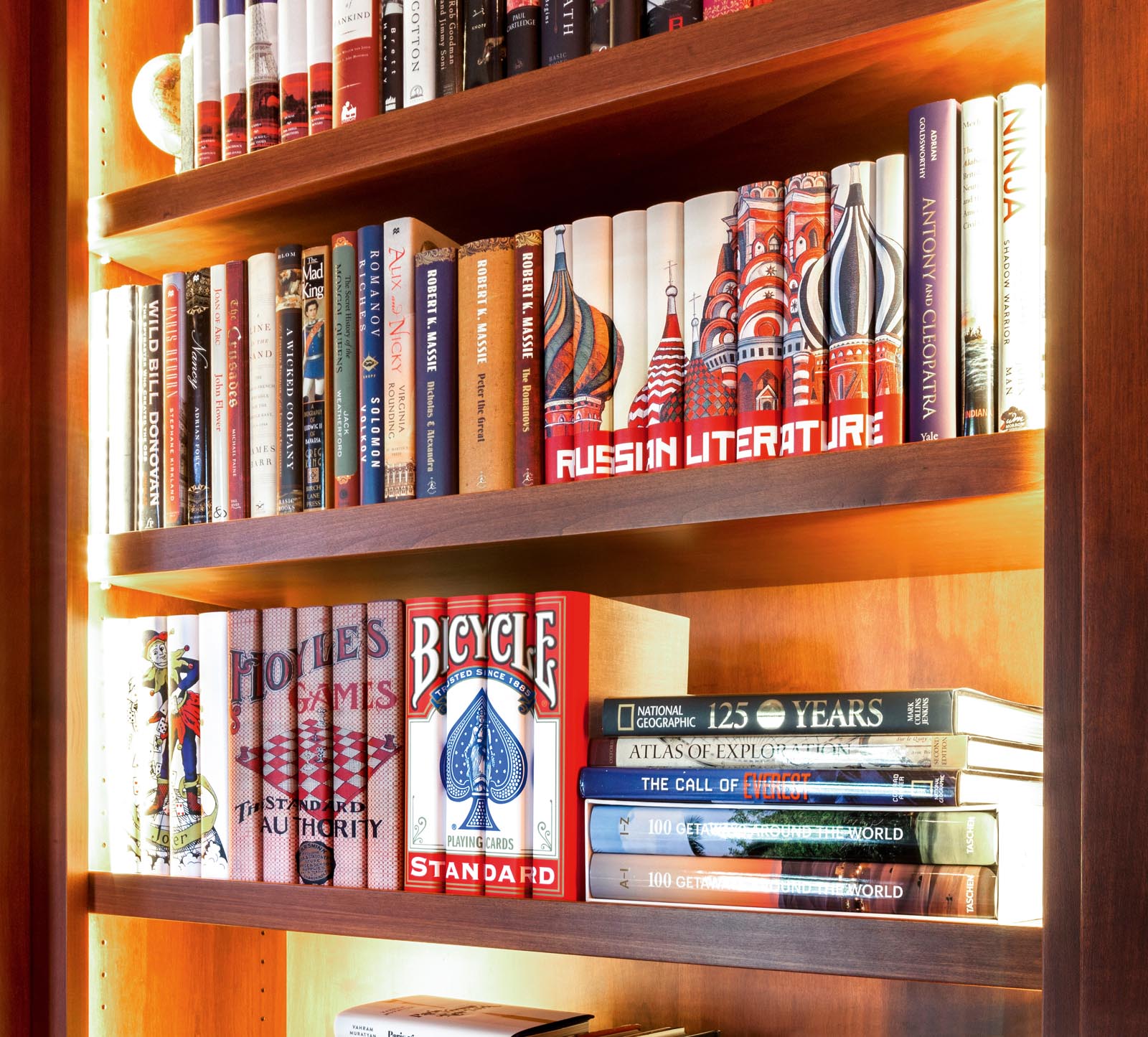

You can have a collection of books that is not a library. Maybe it’s your college textbooks, your deep dive into Eastern religion, or perhaps your collection of crafting books. A lot of people have lots of collections on a variety of topics. Over time, as our interests change, our books don’t always represent what we are interested in in the here and now, or they don’t do so proportionately to our interest level.

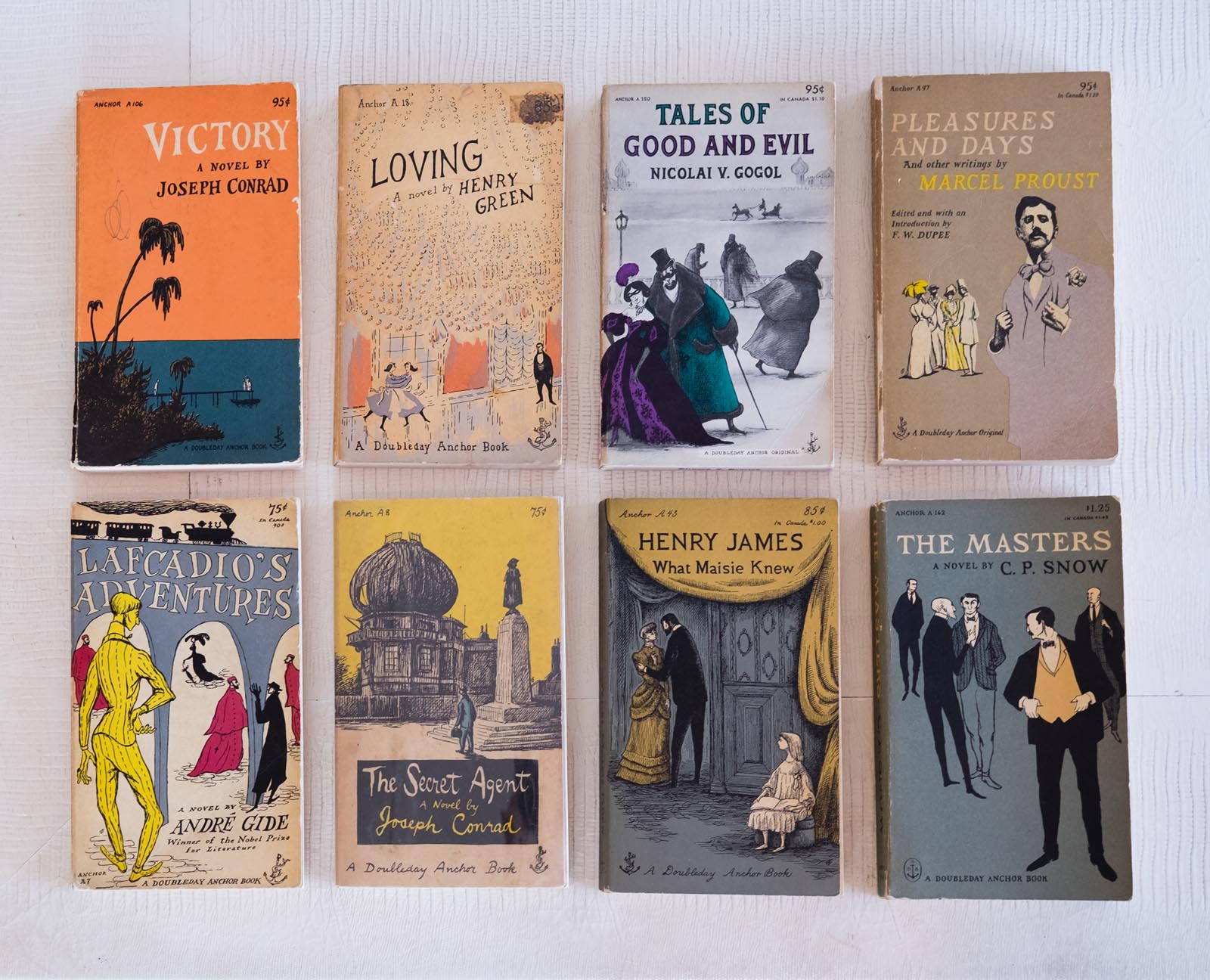

Elizabeth collects paperbacks that feature covers designed by Edward Gorey—not for the stories inside, purely for the covers. You can buy a book for its cover and build an entire collection of books. Those aren’t the only books in her house—it’s just one of her collections and it makes traveling really fun when she finds a new Edward Gorey edition to bring back home. Owning a book for its cover, its illustrator, or whomever gave you the book is just as valid a reason to own a book as the words on the pages.

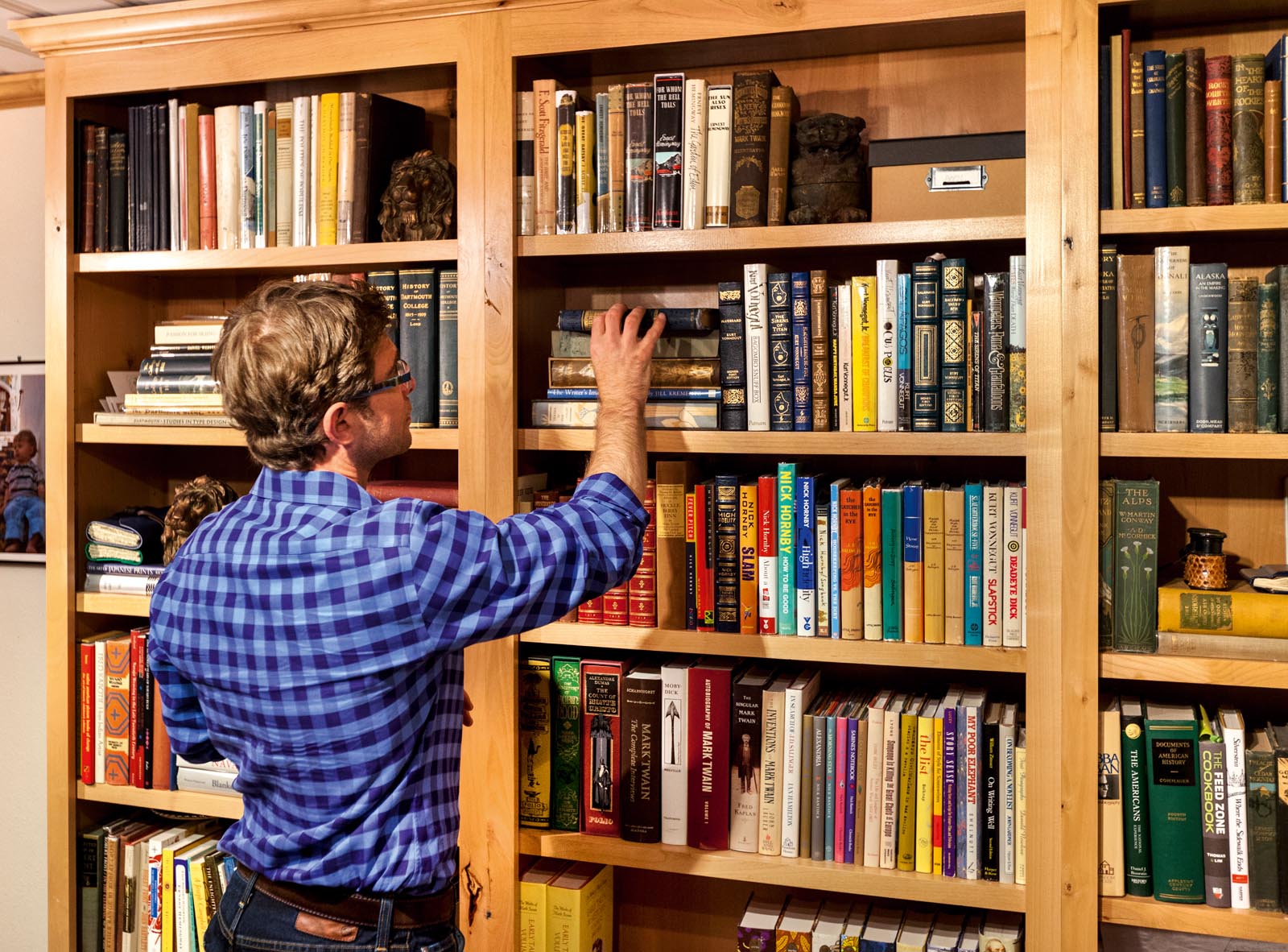

Thatcher has a collection about Colorado—approximately forty books. He doesn’t have a library of books on Colorado, there isn’t enough room on the shelves. However, he does have a library of a few hundred books that includes a variety of collections comprised of books about Dartmouth College (where he went to school) and the complete works of Kurt Vonnegut (one of his favorite authors). At the time of writing this book, he was thinking about selling his collection of books on Navajo rugs in order to free up some space.

Credit: Christine Lane.

The idea of a library of books conveys something much larger than a collection of books. You can fit a collection on a shelf or on a few shelves. A home library is typically at least one room with bookshelves on multiple walls, but of course this criteria is fluid. A library can take many sizes, shapes, and forms.

A library lives on its own, whether it serves an entire community or one person. A library has its own unique identity, an element of “otherness” that is bigger and broader than a collection of books that carry a single theme, such as an author, a subject, or a style.

To illustrate how collections can be consolidated and highlighted within a library, a recent project in Texas is a good example. The client engaged Juniper Books to help them curate a two-story library in their new home. They wanted us to assist them in organizing the books they currently had while also elevating their current collection with additional books curated by us. The clients had approximately two hundred books that were important to them, and had room for about two thousand more books.

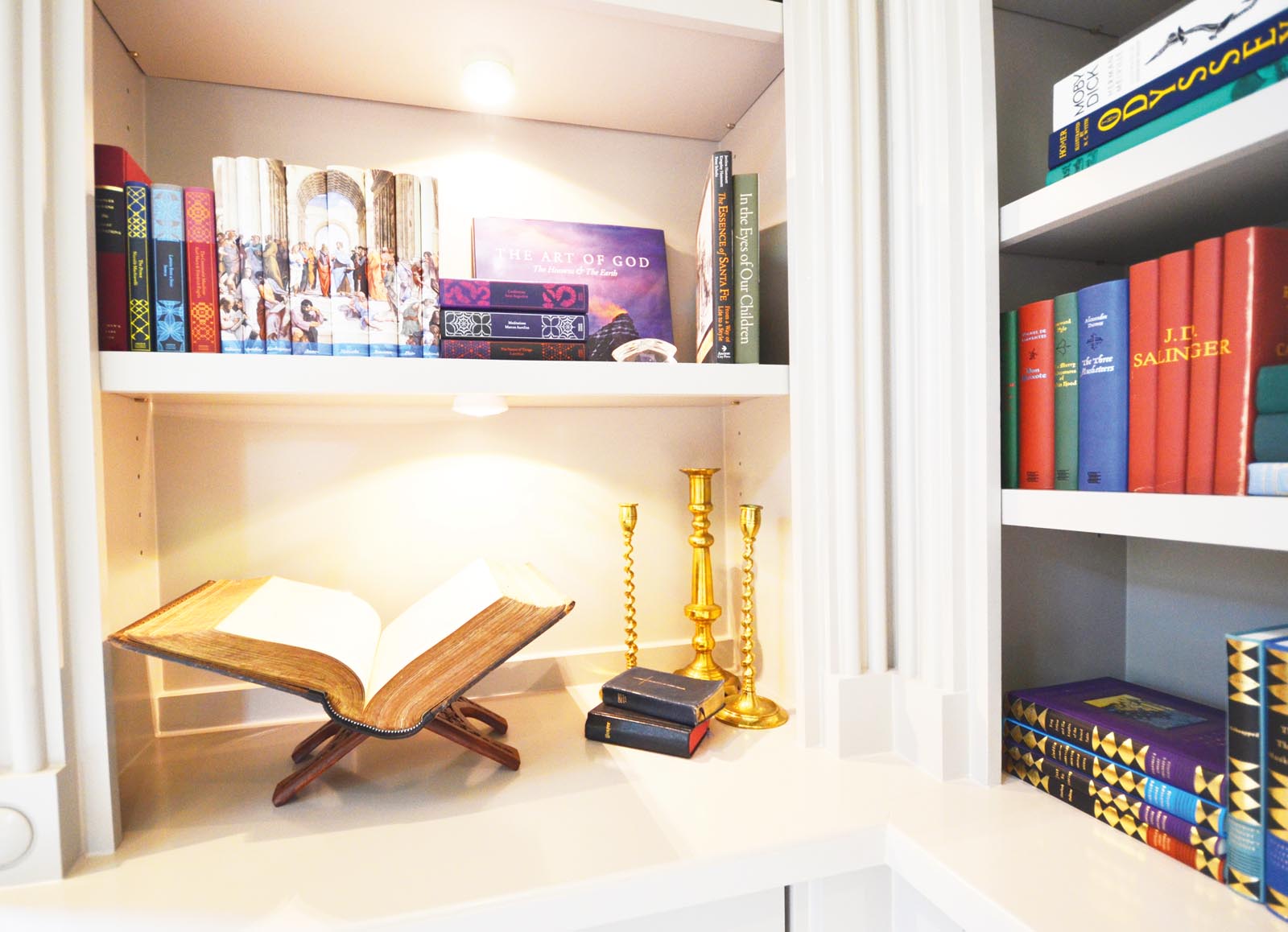

When Thatcher went to the home, he first set about getting a feel for the books they had on the shelves. In one corner of the room was an old family Bible. Scattered throughout the room were various prayer books, books about religion and spirituality, and books about religious leaders. Thatcher brought all the religion and spirituality books closer to the family Bible, then placed prayer books, hymnals, and other family heirlooms in adjacent spaces.

Faith was important to the family and so after the books were reorganized, that fact was presented much more clearly to anyone who saw their shelves. Their “collection” of religion and spirituality books now was highlighted within their “library” in a way that was commensurate with its importance to them.

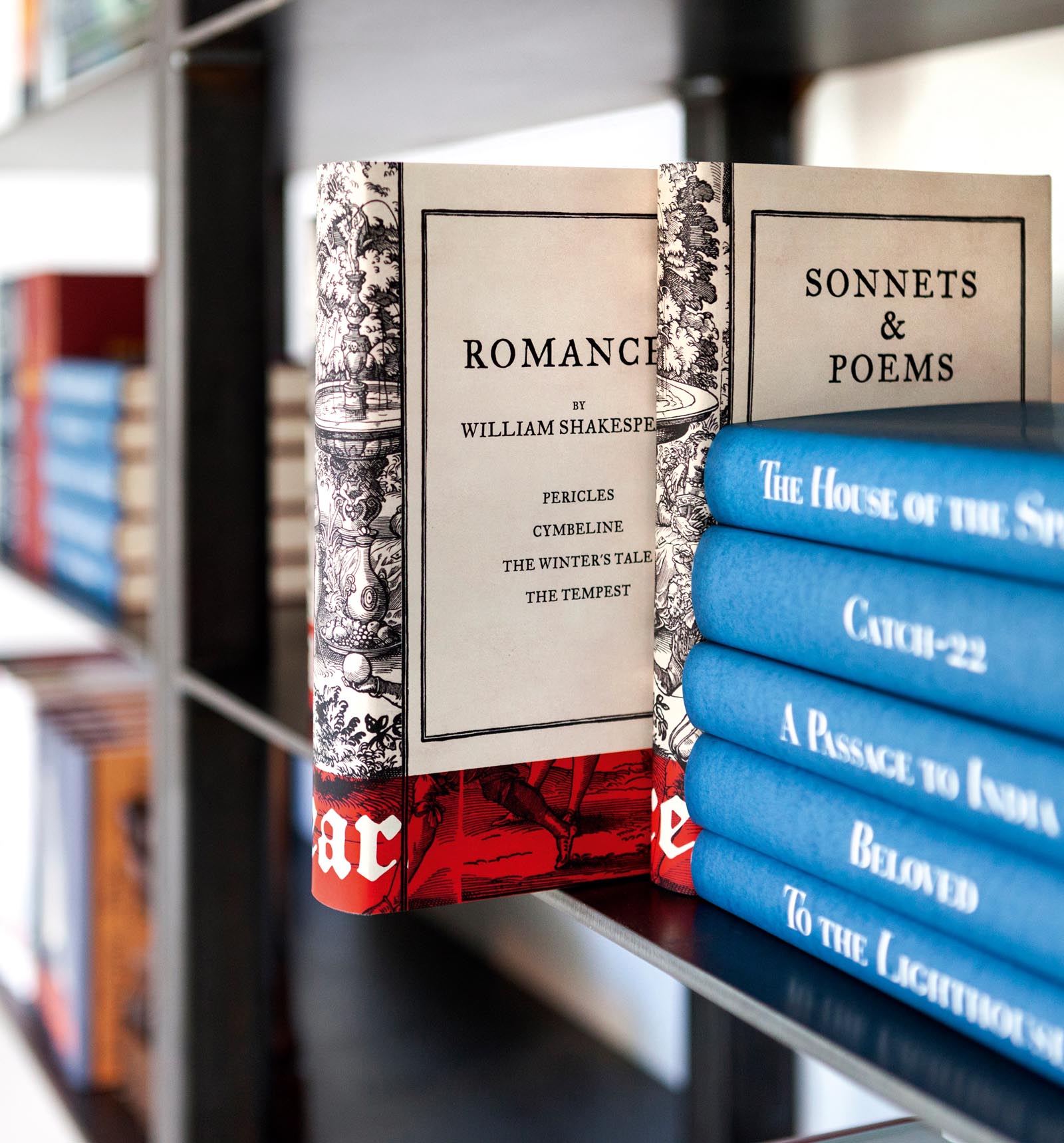

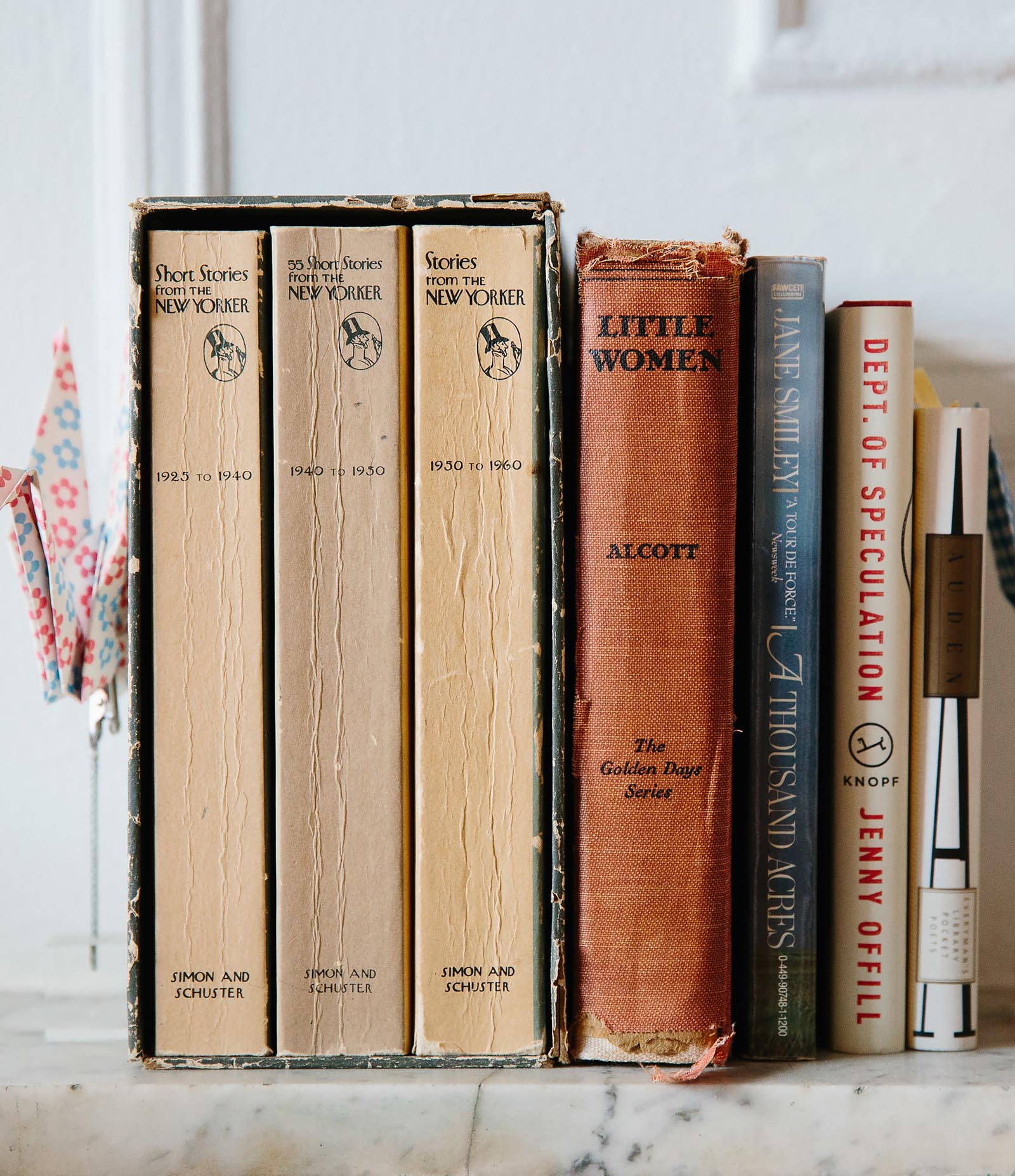

Credit: Christine Han. Features the home of Helen Dealtry.

Credit: Christine Han. Features the home of Christene Barberich.

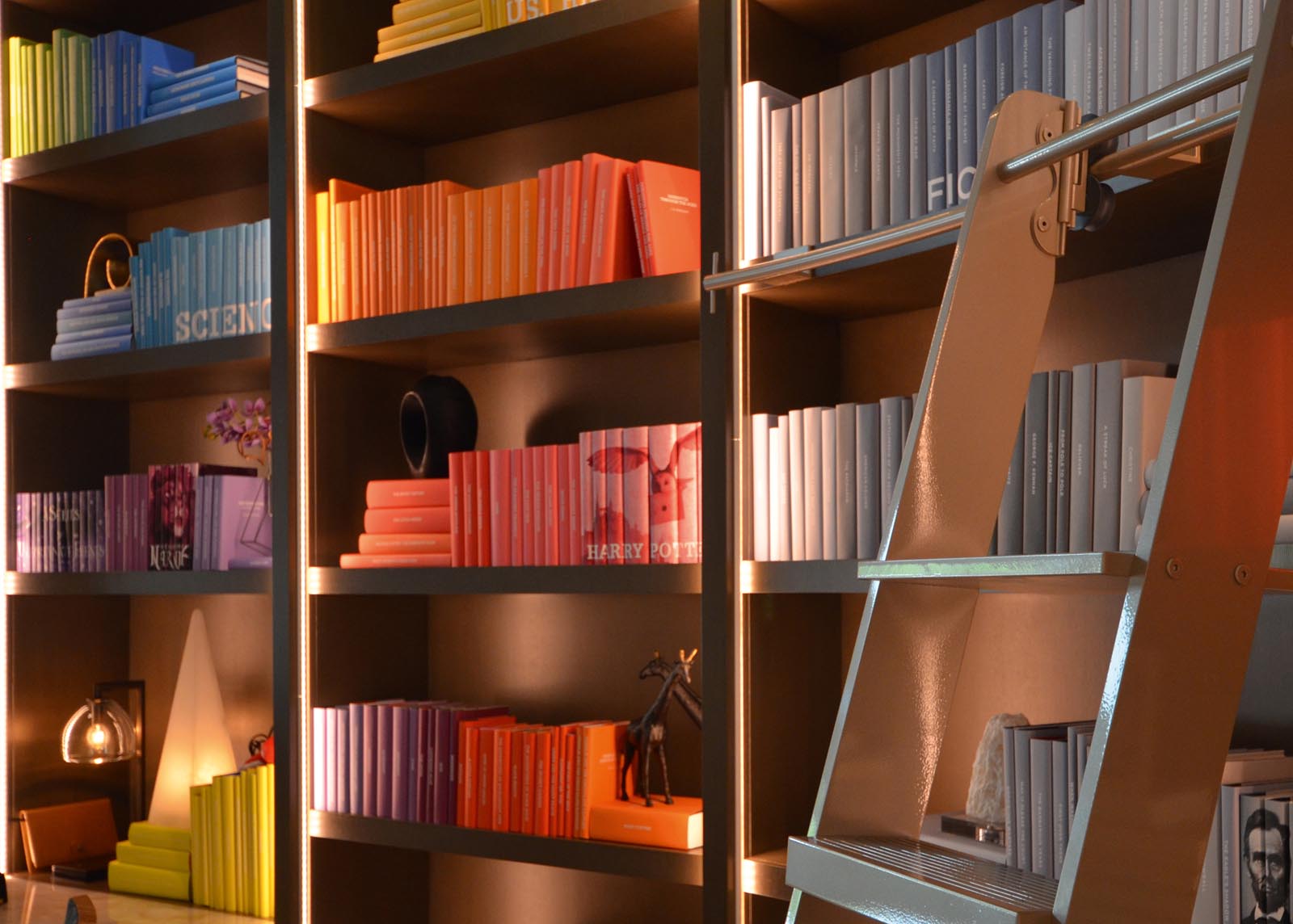

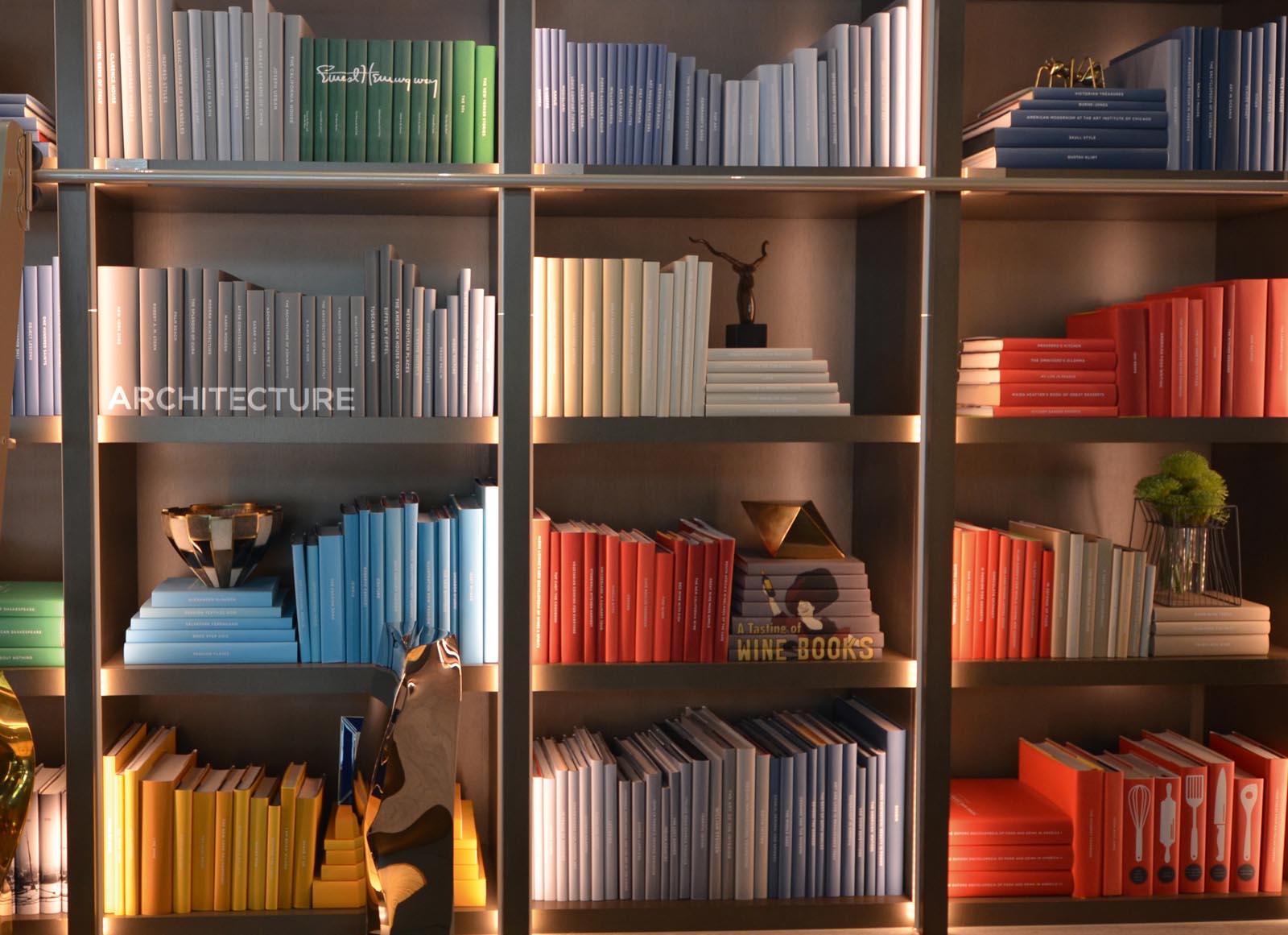

Another client engaged Juniper Books to build a library that would be the center of their open–floor plan house. They did not have any books of their own that suited their vision for the library, so Juniper Books would curate them all. They envisioned the library as a central gathering place for the family and a decorative piece for a truly stunning home.

The bookshelves were the centerpiece of the home and the color scheme throughout was mostly neutral: black, white, cream, gray. When Thatcher reviewed the drawings sent by the designer—Stephanie Moore-Hager—from Dallas, he figured that they would want to continue the neutral palette onto the bookshelves for a serene look and perhaps have the books fade into the background so that all the other amazing design elements in the home could stand out.

Stephanie, however, had other ideas—she wanted the books to pop with color. The client was interested in having fun and using whimsical touches around the house, why not make the books jump out instead of blend in?

As Thatcher and the Juniper Books team curated the book selections—about eight hundred books on requested subjects—and created renderings to show what the finished shelves would look like, they decided to color code sections by subject matter based on each member of the family’s reading preference—Harry Potter, Lemony Snicket, and Mary Poppins for the daughter; Tom Clancy, golf, and travel for the dad; and books featuring art, wine, and food for the guests. Each book would be jacketed in pop art colors—golf would be green; wine and food, bright red; and the children’s books, orange and purple. At the conclusion of the project, Juniper Books handed over a spreadsheet listing the books and a map of the shelves with a color key included so that the family could find any book with ease.

When Thatcher finished shelving and arranging the books, he went across the living room to take a picture. He then looked at the image on the camera screen. From a distance and on the screen, the books didn’t look like books at all. They looked like jelly beans, a whimsical touch that brought a sense of joy, play, and delight to the space. “How perfect,” Thatcher thought. “Mind candy for the family and their guests to enjoy for many years to come!”

It doesn’t take a large house, a large budget, or a new construction to be able to apply the principles we’ve mentioned here to any book collection or library.

As you look at your own books, think about why you have the ones you do and whether they are the right ones for you and who you are now. Then make a plan to methodically work your way through your books and through your house, one room at a time to transform your books into a storytelling vehicle that really brings joy and meaning to your life. We’ll help you on the journey.

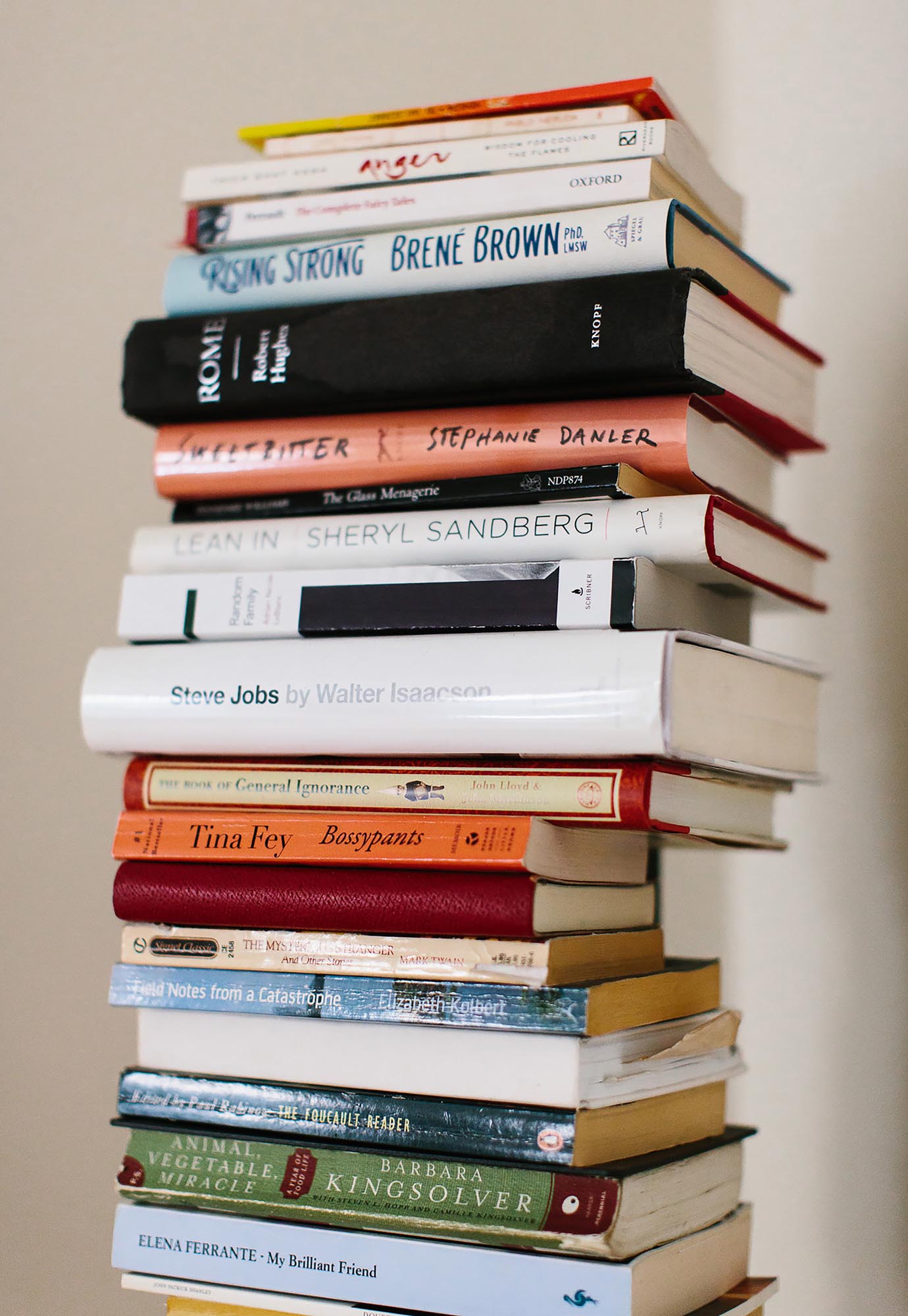

“All the books we own, both read and unread, are the fullest expression of self we have at our disposal. . . . But with each passing year, and with each whimsical purchase, our libraries become more and more able to articulate who we are, whether we read the books or not.”

—Nick Hornby1

Hornby’s words on the previous page beautifully encapsulate both what we think a library is and can be for someone. Yet, this truth that feels so inherent and timeless begs the question: Were private libraries always so revelatory of one’s character, so personal?

After the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press, there was much greater access to books, yet the locus of control still remained mostly with church and state. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, monastic libraries were essentially the public libraries of the Middle Ages, as the larger religious houses served as the center of culture and education. In short, the church was at the cultural center of the axis for ideas and learning.

However, the monastic library system blew apart in 1536, prompted by Henry VIII’s order for the Dissolution of the Monasteries, an attempt to separate the Church of England from its base in Rome, deemed necessary because two popes denied him his desired divorce from Catherine of Aragon2 in order to marry Anne Boleyn.

In response to this dissolution decree and continuing Henry VIII’s desire to sever England’s connection to Rome with an even greater fervor, the commissioners of King Edward VI looted university, college, and monastic libraries, utterly destroying their contents. It has been estimated that more than eight hundred monasteries were suppressed, and with them eight hundred libraries destroyed.3

Transfers of power tend to bring with them increased chaos and in this case book-burning reached a fever pitch. As documented in Geoffrey Moorhouse’s The Last Divine Office, “Bonfires of books (ever a sign of something nasty on the march) flared up across the land, the more conservative bishops were replaced by men who rejoiced in flames.”4 How does one dismantle a culture? Dismantle the books.

Thankfully, not all books were burned as individuals stole them for their personal collections, and this selective theft helped protect countless historical titles from being lost forever.5

By the late seventeenth century, millions of printed books were in circulation. Auctions devoted to books began to pop up with frequency, each with their own printed catalogs, an indication of the further democratization of book collecting serving a more widely interested public. The idea of a “personal library” became possible, and started to transform toward the intimate space, as Nick Hornby describes, that we recognize today.

Take a look at your shelves all together. Do your books go together as one coherent library?

Now, look at your books individually. What are the stories you see? Do you have collections of books that are easily identifiable? Should you perhaps move some books closer together in order to tell a story with more impact? We will cover more steps about how to do this later in the book, but you can start thinking about your books and making changes now.

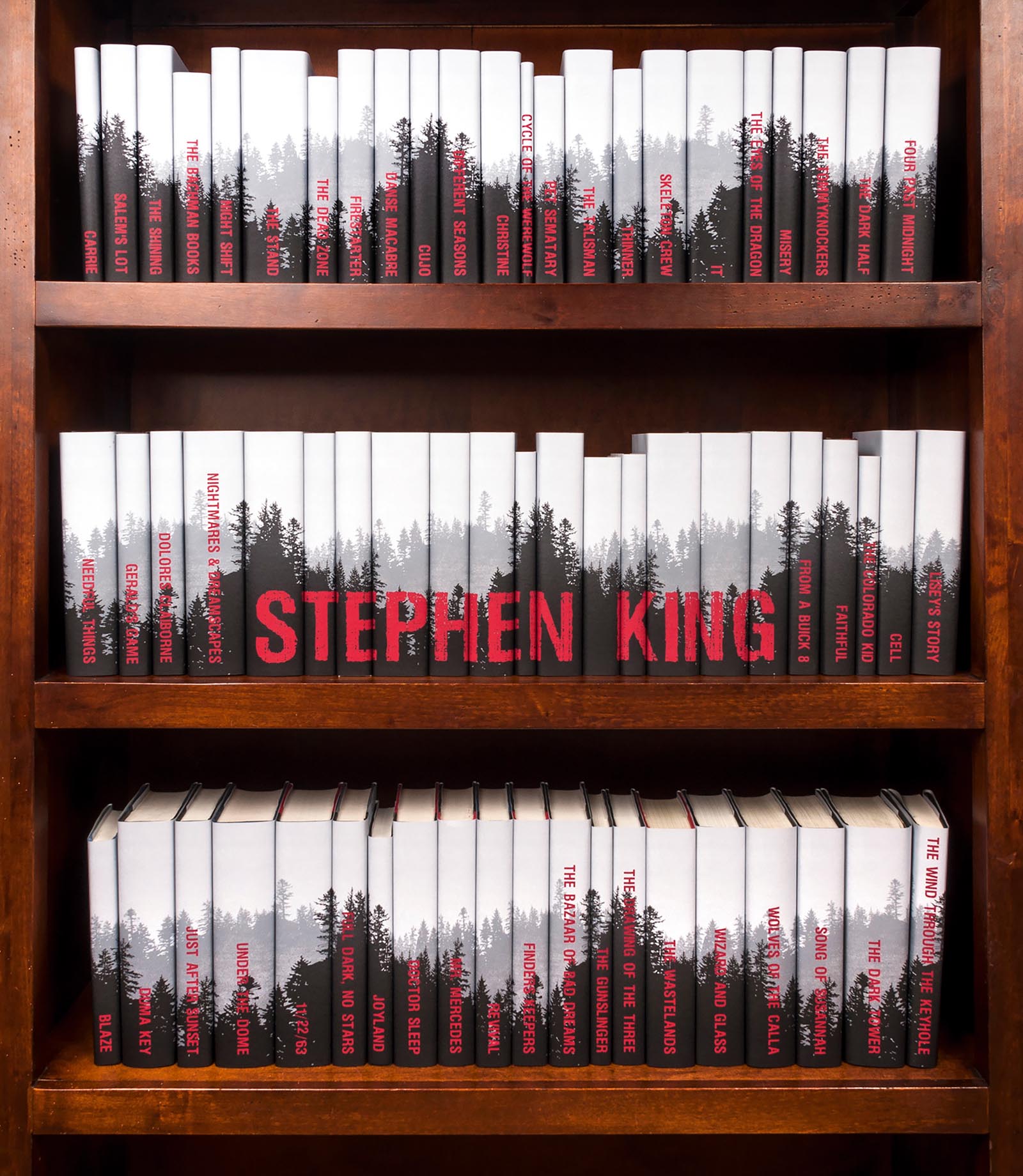

Maybe you decide to build a collection on a certain topic. “I realized we’re missing twenty books that Stephen King wrote in order to make our collection complete!”

“I’m fascinated by stoicism and now that I can afford hardcover editions, I want to see how many I can find.”

“Leather bindings of classic British spy novels are what I want. I’m going to find as many as I can and then find a bookbinder to make me more!”

“Female poets of the nineteenth century—that’s my thing. Leather, hardcover, paperback, I don’t care. I want as many I can find. The more obscure the better.”

Maybe you discover that you now want a library, and if you have the space and the resources to build one you are very fortunate.

To paraphrase Field of Dreams, “Build the library and the books will come.”