The more books you have at home, the better your child will do at school. That was the conclusion of two economists in 2010, Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessman,1 who analyzed student performance and households across international lines. The research was conclusive: if you have two bookcases in your home, the kids will perform well. It’s not necessarily that they read every book in those bookcases, it’s what having two or more bookcases in your home says about you and what is important to you and your family—education, reading, parenting, and so on.

We could just drop the mic here. Get some bookcases, fill them up, and everyone in your household will accomplish more in the world. But let’s break it down into actual steps, to move beyond simply picking up a few bookcases from Ikea. Let’s instead meaningfully fill them and bring a personal love of reading to the family, including the kids!

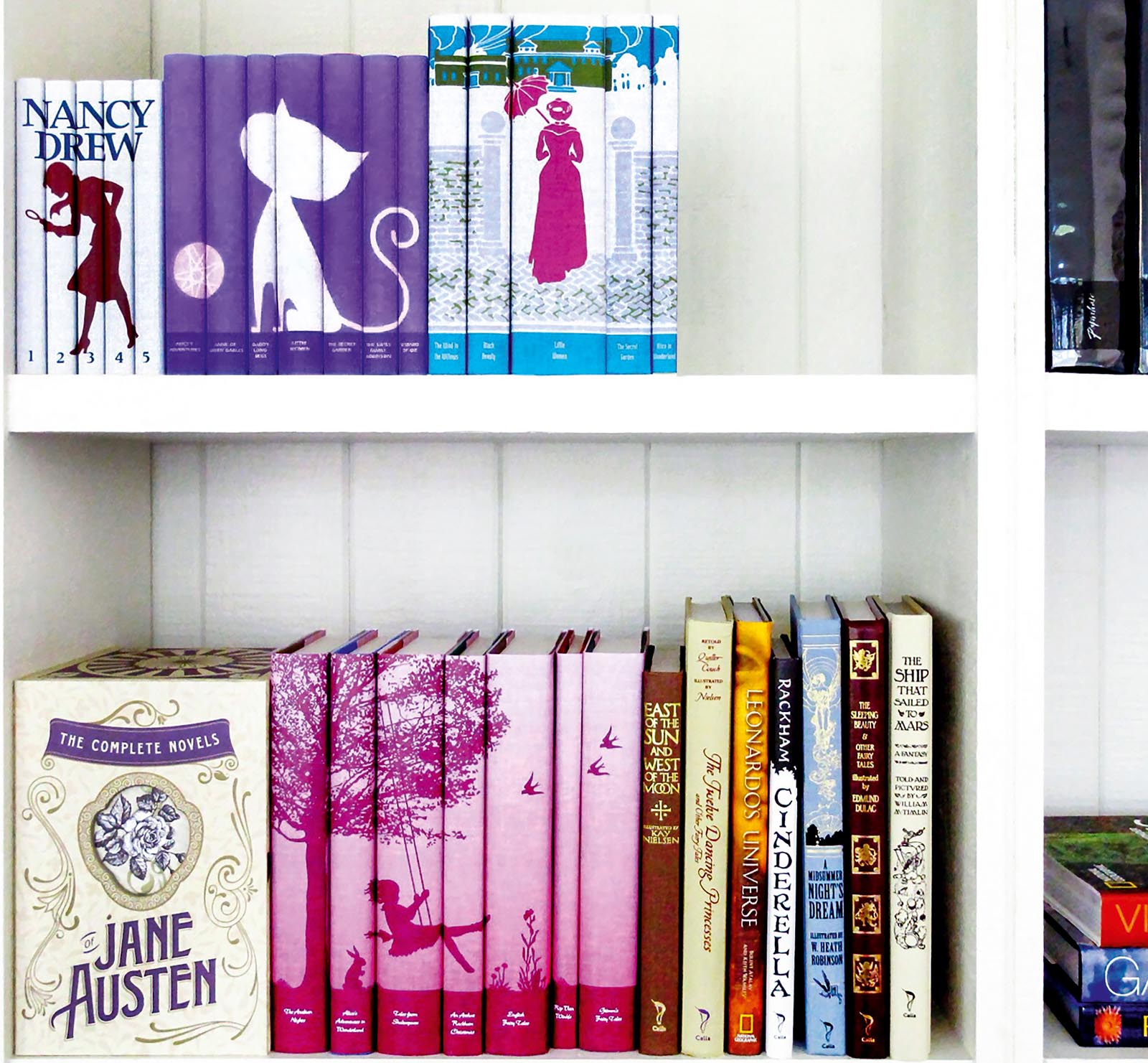

Credit: Nicki Sebastian. Features the home of Elizabeth Antonia.

“Reading is the sole means by which we slip, involuntarily, often helplessly, into another’s skin, another’s voice, another’s soul.”

—Joyce Carol Oates2

Instilling a love of reading is giving your child a profound gift: of dreams, imagination, escape, connection, and empathy—that essential ability to see the world from a different perspective and walk in another’s shoes. As adults, we ideally seek these shifts in perspective found in books somewhat intuitively. How do we foster this love of reading in our children?

The first step is simple. By merely choosing to keep books in our home we open up avenues of discovery and growth, even before we crack the spines to read. That stack of library books in the corner or the ones piled by our beds all possess a palpable energy that is uniquely a book’s own. We’ve all felt this force contained between the covers of a printed book, indescribable, yet so very vital and present. And this energy only compounds once we begin to read.

When our children see us reading, they begin to follow our lead. They may begin this journey as babies and toddlers, leafing through our books as they pretend to read themselves, playing with the form of the book by tearing out all of the pages, or using their own board books as building blocks. The options are endless and each piece lays the foundation for a deep love of the printed page.

When I was expecting my first child, my closest friend started our daughter’s library with a few of her own favorite books from childhood, each book inscribed with a personal message. My daughter’s favorite from this collection is Swimmy by Leo Lionni, a book with which she presently feels a deep connection as she knows that it’s been hers, on her bookshelf, since birth. She recognizes every tear, every crease, and bit of wear that comes with a book that (like that famous stuffed toy from The Velveteen Rabbit) is well loved.

As my daughter has gotten older, she’s planned the books she will pass on as an adult, carrying forward a love of books so beautifully represented in this first gift. She may not always hold the story of Swimmy as close as she does now, the plucky fish who found her essential spot within the school. However, she will carry the context of the gift, that nugget that spoke to her as a young child when she understood this was her book, given to her by someone who loved her even before she was born. These feelings live on every time she looks to her bookshelf and sees that familiar, beloved spine.

Credit: Nicki Sebastian. Features the home of Elizabeth Antonia.

Credit: Nicki Sebastian.

Building a library with a child can be one of the most rewarding and fun experiences for both child and adult. Those early independent reading years (from ages six to ten) are gold. Children begin to show great independence with regard to preferences, yet still value an adult’s essential guidance. It’s a time when kids are sponges, absorbing everything around them and forming their own tastes, showing glimpses of who they will become.

While there exists a world of possibilities with regard to kids and reading, we know that it can feel daunting. Questions and fears abound. What if my child doesn’t share my love of books? What if she only reads graphic novels for the rest of her life? What if he doesn’t read anything at all? Ever?

As parents you want your kids to read and you want to balance your suggestions with an equal amount of stepping aside so they may discover what resonates with them—keeping a mindful eye, yet letting their own curiosity steer their choices. In this day and age, it’s perhaps wise to put the brakes on technology use (such as playing a certain video game or spending time on social media), but it’s rare that you would say “stop reading that book.”

Maybe in the teenage years they start to read more things you aren’t comfortable with. Do you stop them? Do you steer them away from reading so many vampire novels? Are we acting like the church or state banning certain books within the home?

It’s a difficult question, and perhaps (as so many things do within parenting) falls to a case-by-case basis as we remember the flip side: telling someone they can’t read a certain book only serves to make that title more desirable. If your children want to read something and you say no, they are far more likely to seek out a copy and hide it under the mattress, reading late into the night by flashlight—and is that so bad?

Credit: Nicki Sebastian.

There is so much pressure as parents to do things right, and yet kids learn so much from us just being who we are, simply doing what we enjoy doing. If you love to read, let your kids see you reading. Kids home on a snow day? Let the kids play while you curl up in the chair with a mystery—it’s a delight for you and for them.

One of the most magical things about books is simply that there are so many available to us, and with that comes the freedom to choose what to read. There is the perfect book, genre, style, and way to read for every child, even a reluctant reader. If we slow down and listen to their cues, we can then discover what they are naturally drawn to and what they like.

As adults we have a conception of who we want to be through our favorite books—who we are presenting to the world—and kids are the same. With kids, it is a fluid journey as they change their minds frequently, from Dr. Seuss to Roald Dahl and beyond. Let kids discover who they like (without boundaries) and don’t be afraid if their stories are different than yours and if their preferences keep changing. Their sense of self will emerge from the experience.

Credit: Nicki Sebastian.

The following are practices learned from Elizabeth’s reading experiments at home and her own early memories as a somewhat reluctant reader:

We started a new practice in our own household at the new year. Each night, the entire family heads to the living room for an hour or so. The only rule imposed is that it is a work-free zone for my husband and myself. No phones. No computers. Our girls may finish their own homework during this hour, but we adults are simply reading books that we enjoy. We (my husband and I) realized that we needed to do this first for ourselves, to consciously carve out a little peace in the day with our phones turned off. As we committed to this practice, we noticed that our girls were picking up their own books and relishing this time spent reading as a family. It quickly became the most treasured part of our day and creating this space to read casually together (and also trusting that there is time to step away from work and the hustle of life) has been life-changing for us as we’ve discovered that there is always time to read for pleasure.

Credit: Nicki Sebastian. Features the home of Elizabeth Antonia.

I try to place no limits on what my girls read—and this tip was born out of my own childhood as well as my husband’s. I absolutely fell in love with reading when I was eight or nine years old, and my first love was one particular series—and definitely not a classic. I wrapped myself up in the Sweet Valley Twins series and books by Christopher Pike and John Bellairs. These books certainly weren’t what my parents would have chosen for me, but they gave me the freedom to choose for myself and I dove in.

My husband had reading difficulties as a child. Because of this, no books were appealing to him and so his parents gave him the sports page instead. He loved it! Every day he would read the sports page, and through this practice he became a reader. It’s in those moments, when a child is reading what they like that a lifelong reader may be born. So I say, let them read—no limits.

Continue to read aloud with your children for as long as possible. Our eldest daughter is almost ten and we still read aloud together most nights, a tradition that I savor and hope will live on for several more years. My own children still love to snuggle in close and listen to a story. I find this is the perfect time to bring in those stories that have grown with us, such as classics like The Secret Garden or Little Women. Also, continuing to read aloud together, even in the preteen years, opens up one more avenue for conversation to blossom with our kids. It’s a magical moment that’s hard to outgrow, because it’s just that: it’s magic.

Credit: Nick Steever.

My youngest daughter has a time in the day that she absolutely craves. She calls it “peace alone” and it was a concept she came to when she was only two or three years old. She is very social, and yet, for a few moments every day—it could be five or twenty minutes—she steals away to spend time by herself in the quiet. During this time she will do whatever she wants. She will play with toys, make up stories, lay on her bed just to stare at the ceiling, whatever fits the moment and the mood. As I watched my daughter grab these peaceful moments for herself, I realized how much we all need that. And so each day, I’ll take five to twenty minutes by myself and my eldest daughter will now do the same. It’s a time to find center, to settle into peace, and to relish the quiet. Each day brings with it more activities, more busyness, and with it, more noise. Yet, for the past few years we have sought out these quiet moments to refresh. The unforeseen side effect has been to create another natural space to reach for a book. As my girls started to crave the quiet and find space within these moments, they also found the space to expand into a story and into their own imagination.

My sister is nine years older than I am and when I was young she would often make up stories with me at bedtime. These were stories purely from her imagination and as she shared them I would weave in my own bits to add and enhance. We would watch as this creation would ebb, flow, and expand to endings unknown and often bizarre. We had so much fun with these stories, many of which I still remember today. My husband and I try to continue this tradition of storytelling with our girls—making up different tales, having them add their own twists and turns. These narrative wanderings help all of us tap into our creativity and fall more easily into our own imagination. And that’s really when we fall in love with a story and its characters—when we can free fall into the world of the story through our own imaginings.

A while ago, my youngest daughter went through a seriously picky phase with food. Nothing was working and I’d reached the end of my own inspired ideas to get her to try the foods we were eating as a family. A friend of mine suggested that I bring her into the kitchen to cook with me, and it worked! The minute she felt that she had a hand in cooking our meal, she dove right in, eating with gusto! She felt pride in the preparation and so was excited to try the meal. With that experience close at hand, I realized the same might be true with reading. When the girls were first learning to read, we started writing stories and turning them into books—folding the pages, sewing the bindings. They created books, which meant they were authors! This cracked books open for them in a new way and made them more accessible. They realized they could create physical books similar to the ones on their bookshelves and so those books became relatable.

Credit: Nick Steever.

Revisit books your children loved as babies. Choose joke books to read or children’s stories with the silliest humor. When you read aloud as they look over your shoulder, divert from the story into a crazy tangent—perhaps Mary Lennox opens the door to the secret garden and finds herself on the surface of the moon! Reading is play. It’s leisure. It’s recreation and it’s fun. The more we can illustrate the play and the fun inherent in reading, the more kids will foster that outlook on their own and seek out space in the day to read.

This final tip is really one that I’ve gleaned from the times I’ve found myself wanting to do anything but read a particular book. Here’s where the obligation to read trips me up every time: I am a part of a book club, and the minute our monthly books are assigned, my first impulse is to go rogue and read another book! It is such a silly reaction, but I know that in that moment I am rebelling against being told what to do. If it feels like homework, I rebel. My daughters often have the same instinct. So I try to keep it light, keep it fun, and if twenty minutes (or even five) isn’t going to happen that day, I just let it slide.

Credit: Nicki Sebastian. Features the home of Elizabeth Antonia.

Credit: Nicki Sebastian.

The concept of “childhood” didn’t really exist until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Let us repeat that. Childhood, as a recognized phase of development, simply didn’t exist. Children were seen as incomplete versions of adults. This viewpoint is amazing to contemplate today, with tens of thousands of parenting books and blogs guiding contemporary parenting. Because childhood was not viewed as a distinct state of being, there was no separate category of children’s books or children’s literature.

Early concepts of childhood slowly materialized in Europe in the seventeenth century as adults started to see children as distinct humans, wholly innocent and requiring an adult’s essential guidance. In 1690, philosopher John Locke developed his theory of the tabula rasa, in which he posited that humans were born “blank slates” and our ability to process the world around us emerges solely from our sensory experiences. Taking this theory further to its practical application: since a child’s mind was perceived as blank at birth, it was then the parent’s job to instill the child with correct ideas.

Locke understood that children would respond to books that were fun and simple in both subject matter and tone, shifting the experience of gaining knowledge toward play rather than work—a distinctly progressive idea for the seventeenth century. Furthermore, Locke recommended adding illustrations to books, bringing even more joy to a child’s learning experience.

With Locke paving the way for the concept of childhood, the modern children’s book emerged in mid-eighteenth century England. A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, written and published by John Newbery in 1744, is considered the first modern children’s book. A first of its kind, this volume sought to delight children with a mixture of rhymes, illustrated tales, and games. The book was smaller in scale (perfect for little hands) with a bright-colored cover that further spoke to a child’s sensibility.

Following Locke’s thread of influence further, the nineteenth century brought with it a shift in children’s literature toward the humorous rather than didactic, stories that spoke more directly to a child’s imagination.

Author Hans Christian Andersen traveled through Europe and gathered many well-known fairy tales, transcribing them in a way that resonated beautifully with a younger audience. The Brothers Grimm sourced traditional tales told in their native Germany. Grimms’ stories found such an eager audience that realistic children’s literature lost footing as stories of the fantastic took hold.

The availability of children’s literature increased right in step with the greater numbers of books published in general. As children’s literature grew as a genre, literacy rates grew in kind.

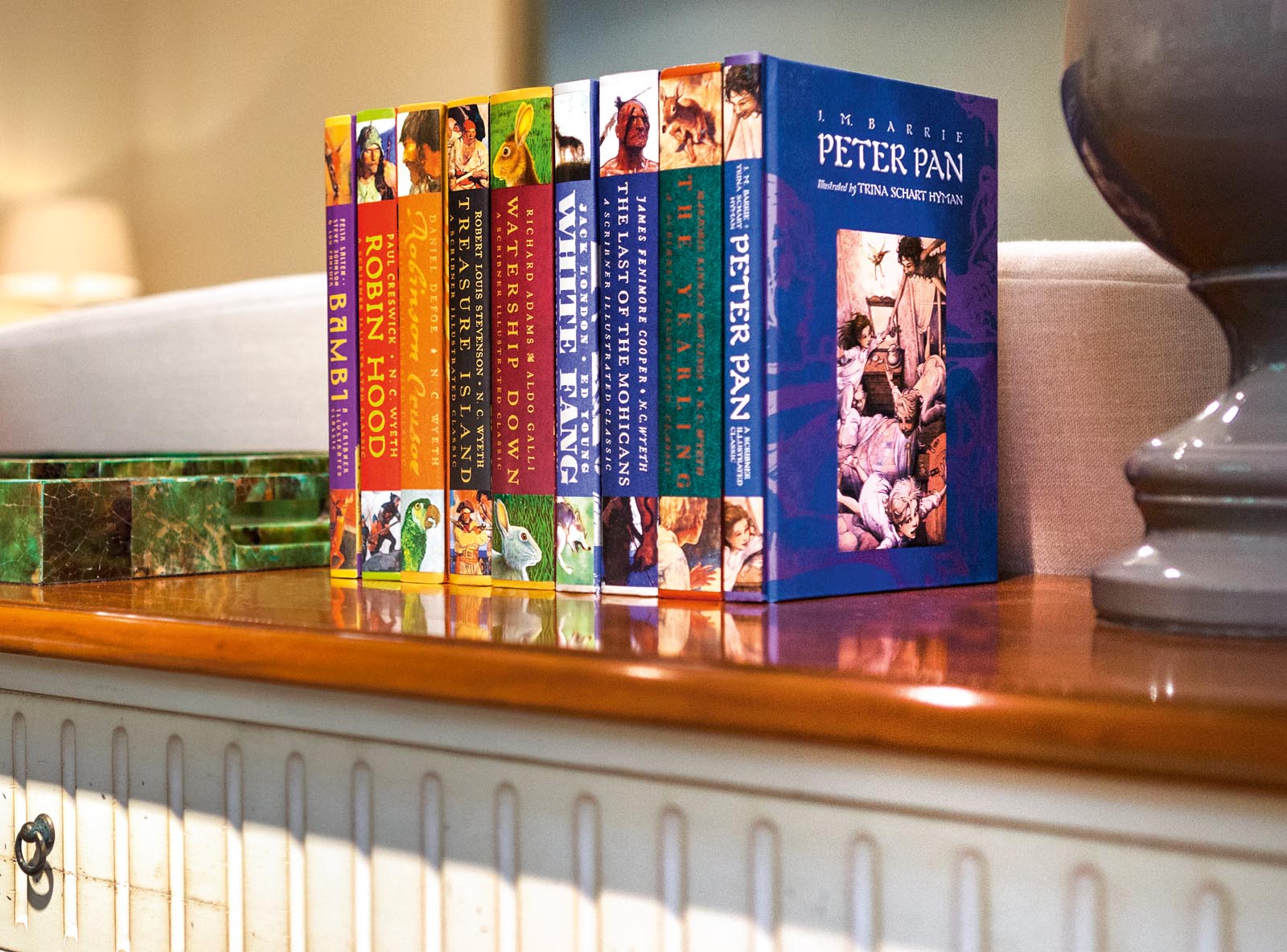

Works we still read to this day found their way to the shelves in the mid-nineteenth century: Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty (1877), followed by Beatrix Potter with The Tale of Peter Rabbit in 1902, to name a few well-known titles. And perhaps the most well known from America is L. Frank Baum’s fantasy novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900. Baum wrote fourteen more Oz novels, following the success of his first.

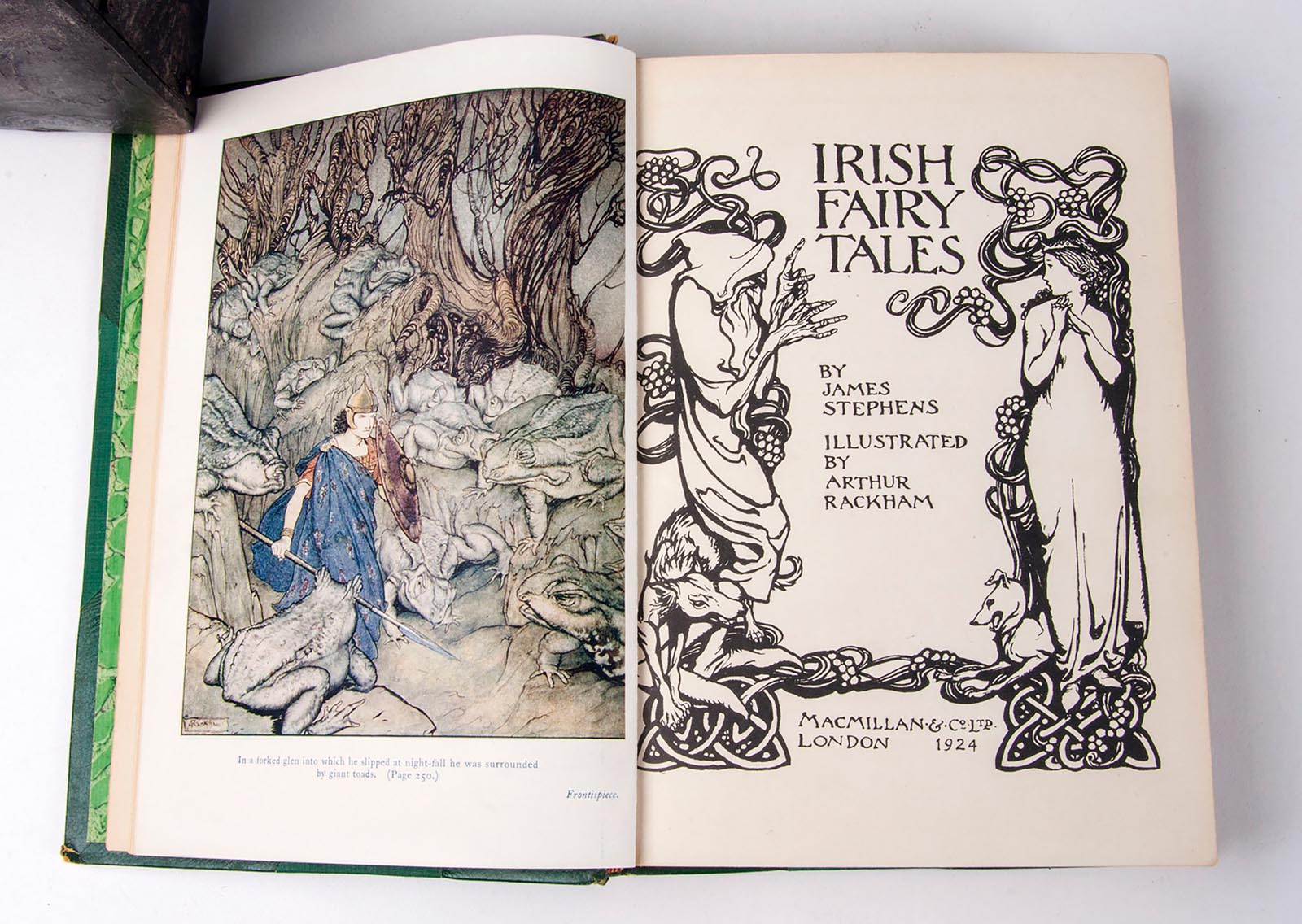

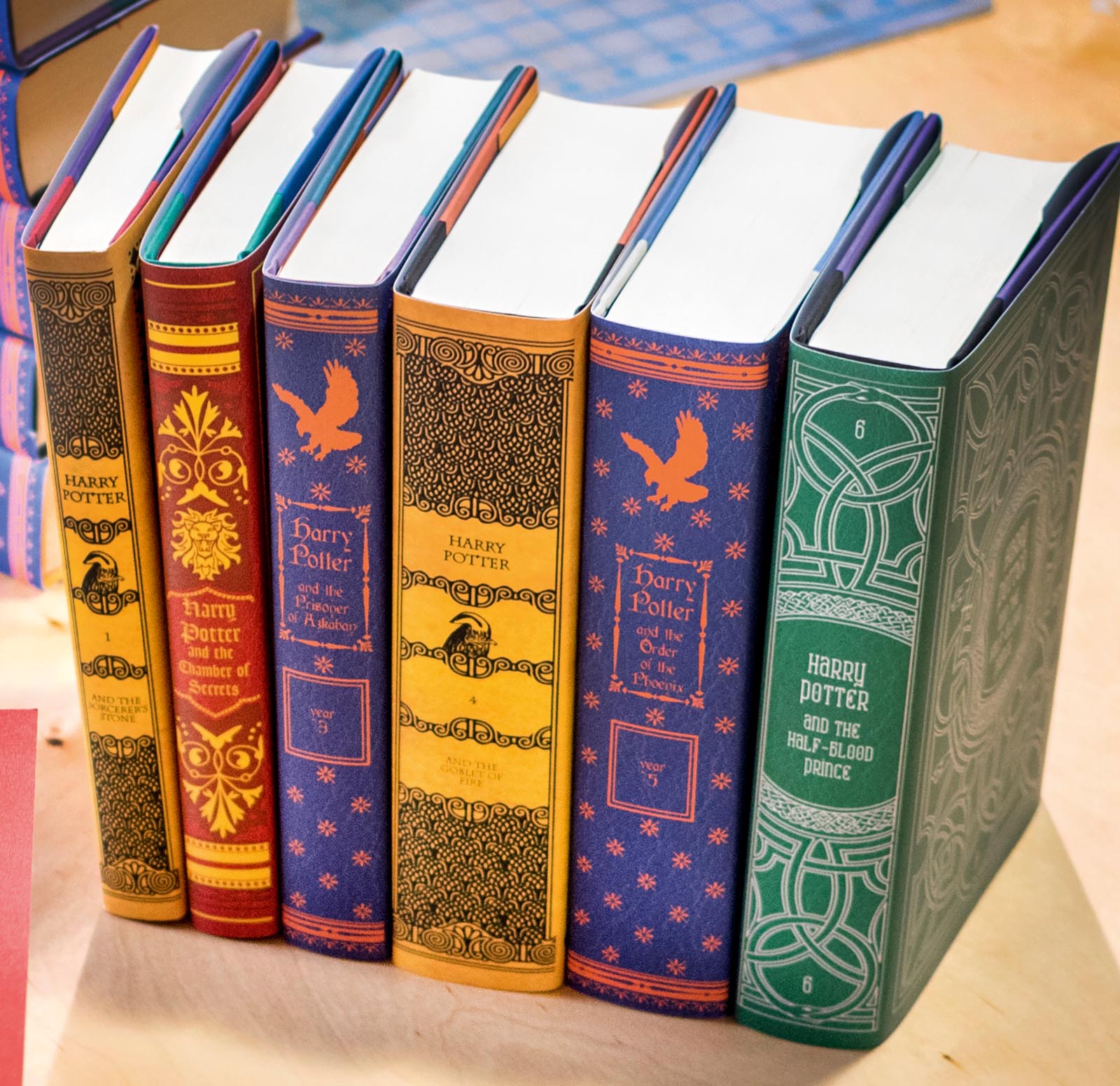

The longevity of these titles, and others like Winnie-the-Pooh and Charlotte’s Web, is remarkable and speaks to the present day desire to collect classic children’s titles. As such, rare and antiquarian children’s books is a growing category among book collectors. Holding an antique children’s book in your hands connects you to the children who held the book before you and perhaps to your own childhood as well—the books you held, how you felt, where you were, and other memories and emotions.

Well-loved and utilized children’s books are often not in the greatest condition so there is a premium on finding copies that are not excessively worn, scribbled on, or damaged. Personally, we love coming across old books with signs of previous owners’ use—names of the children who have owned the books, the occasions on which they were given, indications of their favorite parts of the books, and so on.

Old books tell stories and when we bring them into our homes and shelves, their stories merge with our own. That’s the magic of books and book collections.