Tommy Craig, Robert Whiteman, and Neil Mclaren at Whiteman’s wedding reception

After Robert met the Fat Man at the Playmate Club, he started going there regularly. It soon became the centre of his night life. The Playmate was located in Vanier, a tough working class area that had once been an independent municipality but was now amalgamated with Ottawa. The entrance to the club was off a quiet little side street lined with modest homes.

On the outside, the Playmate Club appeared to be small and insignificant. A red and white sign over a worn white wall announced its existence. Anyone could tell that this was a very private place. There were no windows in the walls or in the entrance door. Two bullet holes pocked the surface of the front wall beside a sign that read: MOTORCYCLES PLEASE USE RESERVED AREA IN BACK.

Inside the club, the show room and bar were below street level. Halfway down the stairs there was a glass showcase of snapshots showing past and present strippers in a variety of provocative poses. The showroom itself was a seedy maze of chrome chairs and red upholstered benches facing the small elevated stage in the centre of the room. There was a bar in one corner, a pool table in another, and more bullet holes in the walls. A sign high on one wall says: NO TOUCHING, NO DRUGS. Another sign announced that lunch was served from 11:30 to 1:00.

The food was passable and the entertainment stimulating, making the Playmate a popular spot. During the day the clientele was reasonably consistent; civil servants of all ranks and businessmen from all levels of commerce would drop in for the lunchtime performances. A different crowd came in at night. There were always a few straight Johns out for a naughty evening on the town but many of the night people who gathered at the Playmate Club lived on the dark side of the law.

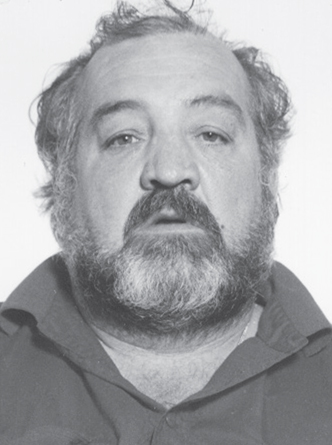

This was the domain of Tommy Craig. Barrel chested and broad of girth, the Fat Man was a Runyonesque character of gigantic proportions. He loved being the centre of attention and everything he did, he did with flair. This ran from his hearty greeting of friends to his raucous outbursts of laughter that could be heard over the din in the club. A connoisseur of fine jewellery, he wore two huge rings on either hand that were worth a prince’s ransom. He was very clever and loved to discuss issues, but with little formal education he could mangle the English language with expressions like: “That don’t bother me, I’ve got no squirms about that.”

All of this made him an endearing character who was normally pleasant and outgoing. But he was a moody man; his cheerful personality masked a smouldering anger lurking within his massive bulk. It didn’t take much to make the Fat Man miserable. In the Playmate Club, people were wary of crossing him.

He ruled the place with an iron fist. No matter how big the troublemaker or how many were making trouble, the Fat Man could handle the situation. A lot of his “handling” was done with back-alley diplomacy; he would always try to talk people into behaving – sitting down, cooling off – but if they persisted in causing a ruckus, Tommy would fight. One way or another, he had been fighting all his life. His nose had been broken so often it was almost flush with his face. Tom developed his confidence as a fighter in reform school. He’d always had a mean streak in him, and even though he wasn’t big as a kid, he had never been afraid to fight. But it was in reform school he discovered he was agile and quick with his hands and could take on anybody.

As Tom got older, he was never known to lose a fight. When he began to put on weight he developed a powerful, heavy punch and he learned to get it in first. That one punch usually did the job. Not only did he hit hard, but the devil’s head ring he wore on his pinky finger cut an opponent badly. Usually when the blood started flowing the fight was over. On the rare occasions when Tom had to fight more than one person at the same time he would use a baseball bat which he kept in the fridge behind the bar.

Tommy was, as they say, well known to the police. He had been in trouble since he was a kid. His mother and father were both drunks who cared more about drinking than they did about raising their four children. Tommy grew up unsupervised and, by age six, he was out of control both at school and on the street. By the time he was seven, he was deemed incorrigible and was sent away to training school (reform school) in Cobourg, Ontario. There, he says, the “sadistic bastards” beat him to a pulp to make him toe the line. The beatings put welts on his back and a huge chip on his shoulder. He developed an intense hatred for authority figures, especially school teachers.

The most valuable lesson he learned at Cobourg was to stand up and take care of himself. Most of the kids there had been abandoned; now they were being abused. Filled with hate and wild with rage, they tried to take out their aggressions on one another. Tommy soon realized if he was going to survive, he had to protect himself.

After seven torturous years at Cobourg, Tommy was shipped back to his mother who sent him off to Ottawa Tech for his high school education. His career at Tech ended abruptly when a teacher singled him out and embarrassed him. Tommy hit the instructor and was given a lengthy suspension. Rather than hang around the house in Ottawa, he ran to Montreal where, surviving on his wits, he lived on the streets for a couple of months. When Tommy finally returned to his mother’s place in Ottawa, a probation officer picked him up and returned him to Cobourg. By now he was too old and too big for them to handle so they shipped him off to Bowmanville Training School, home for over 200 wayward boys.

Things were better for Tommy there. He was big enough to protect himself and could fight back if someone tried to abuse him. He stayed at Bowmanville for eleven months, until he was accused of being a lookout for an escape attempt by three of his friends. That earned him a trip to the Guelph Training School, one of the toughest institutions in the province, a place with tighter security than most provincial jails. Tommy spent the next year and a half behind its bars.

No sooner was he released than he was caught riding in a stolen car with two other boys who were on their way to the infamous St. Joseph’s Training School at Alfred, east of Ottawa. Their intention was to go there and avenge a beating and abuse that a Christian Brother had inflicted on one of the boys in the car. For this aborted caper, Tommy was given eighteen months probation.

Tommy Craig, Robert Whiteman, and Neil Mclaren at Whiteman’s wedding reception

“The Fat Man,” Tommy Craig. The police said he moved more goods than Simpson-Sears.

In order to survive he turned to life on the streets, buying and selling almost anything. Through his contacts, Tommy became more intimately acquainted with the Ottawa underworld.

“I might only have a grade eight education,” he says, “but I got a doctor’s thesis about life on the streets.”

If someone wanted to sell an item, Tommy bought it and resold it at a profit. If someone wanted to buy a particular item, Tommy could get it for them at a very good price. Over time, he came to specialize in jewellery. He knew its value, its price, how to remove stones from their settings, how to melt down the gold settings. Some of the jewellery, bought wholesale in Toronto, was legitimate. Most of it, which he bought from thieves on the street, wasn’t. Because Tommy didn’t do any B & Es himself, he managed to stay out of trouble with the law. However, in 1964 he got caught with some stolen property and was charged with possession and breach of probation. That sent him away for a year to the Burritt’s Rapids Detention Centre near Kemptville.

In 1968 he was arrested for breaking into the office of Bruce Firestone, a wealthy Ottawa businessman. Tom and an accomplice stole Firestone’s safe, but didn’t get very far before the police picked them up and found the safe in the trunk of their car. Caught red-handed, Tom pleaded guilty and was sent to Collins Bay Penitentiary for two years. At the “Bay” his contacts with the criminal world expanded.

When he got out of prison two good things happened to him. First, an Ottawa detective, Steve Ladore, got him a job driving taxi. It was the first honest job he’d had in years. Secondly, in 1970 he met a beautiful statuesque blond named Linda Davies at the Chaudière Dance Club in Aylmer. She was a no-nonsense Ottawa girl who liked his brazen personality and breezy style. What’s more, she figured she knew how to handle him. Within months they were married.

Tommy didn’t like driving a taxi. It didn’t pay, it wasn’t exciting, there was no challenge. At the first opportunity he took a job for bigger money as a bouncer at the Bayshore Hotel in suburban Nepean. It was a tough place with lots of bikers but Tommy soon showed he could control the situation. Since most of his fights were over very quickly, it didn’t take long for his reputation to get around. The longer he worked as a bouncer, the less he had to fight.

After he had been at the Bayshore for several months, he was offered more money to come back to Ottawa and clean up the Gilmour Hotel. Linda came with him to work behind the bar. The Gilmour, located downtown on the corner of Gilmour and Bank Street, had a bad reputation as the roughest joint in town.

The Fat Man had a fight in the Gilmour almost every night for three months straight. Before he would fight, Tommy would try every trick in the book to get the rowdies to settle down. He talked with them, he pleaded with them, he bought them beer. The more he tried to reason with them, the more difficult they became. More often than not, they interpreted his non-violent gambits as a sign of weakness. And as soon as they suspected he was weak they wanted to fight him. To their regret, those who tested his weakness found they were sadly mistaken. Some came away with bloody noses; others with broken bones. At the Gilmour, Tommy was like Rocky Marciano: the undefeated heavyweight.

But his dominance couldn’t last forever. One night at the Gilmour there was a nasty scene involving a gentle old lady who used to stop in every night for a few beers on her way home. In her seventies, she was a favourite of Tom’s and popular with many of the regulars in the tavern. This particular night, a gang of bikers, looking for some laughs, tripped her as she was leaving and sent her sprawling on the floor. As she lay there helpless, the crew of thugs sat at their table laughing and mocking her. When Tommy saw this, he went wild. He attacked the pack of hoodlums with his baseball bat. They tried to fight back but they were no match against his fury. Seven of them ended up being treated at the hospital, one with a broken collar bone. However, as it turned out, the fight wasn’t over.

A few months later in the Gilmour, on March 26, 1978, Tommy was asking around for the whereabouts of one of his customers so he could collect a $600 debt. A couple of toughs who were drinking in the hotel told Tom where he could find the man he was looking for. They invited Tom and his wife to come to a poker game after closing where he could have a few drinks, play some cards and collect his money.

At two o’clock in the morning, Tommy and Linda, following directions, went to a “booze can” located in a row house on Somerset Street in downtown Ottawa. Neither of them had been to the place before. When they walked in, the house was ominously quiet. There was a card game in progress in the kitchen and Tommy was invited to sit in on the game. Someone poured him and Linda a drink and the two of them sat down at the table. For some reason, Linda had a bad feeling about the place and whispered to Tommy, “I don’t like the feel of this house. Let’s get out of here.”

“Naw,” Tommy whispered back, “I’m gonna play a few hands. Besides, I want to get my six hundred bucks. If you don’t want to stay, go ahead and take the car home.”

“And what are you going to do?”

“Don’t worry about me. I’ll get a ride home.”

Linda finished her drink and left. As soon as she was gone, some of the card players decided to take a break and left the table. One of those remaining, who Tommy hadn’t realized was a biker, pulled out a .45 automatic. He walked behind Tommy and said, “Tommy, what you did to our guys with the baseball bat wasn’t right.”

Tommy knew he was in serious trouble. He tried to get up to fight but before he could get off the chair, the gunman shot him in the back of the calf of his left leg. The bullet tore through the muscle and shattered both bones in his lower leg.

While Tommy lay on the floor writhing in agony, the biker stood over him and said, “We didn’t want to kill you Tommy, but we wanted to hurt you real bad for what you did to our guys.”

It was almost like a business transaction. Moments later one of the younger guys in the house went to the phone and called 911. The ambulance came and rushed Tommy to the hospital.

When he got to Emergency, he insisted that the nurses take him off the hospital stretcher and put him in a wheel chair. He was carrying $1,700 in cash and wanted to sit up so he could keep an eye on his money. Because his pants had been blown apart, even in the wheelchair bills in huge denominations were falling all over the hospital floor. With his leg throbbing in pain, Tommy was busily twisting his head in all directions, looking for his money and pointing to clumps of cash so the nurses would retrieve it.

Seeing the severity of his wound, the doctors wanted to take him to surgery immediately. Tommy adamantly refused to be put under anaesthetic until Linda arrived at the hospital. He trusted no one but her to keep an eye on his money and safeguard the four rings on his fingers which were worth $50,000. When Linda arrived, he gave her his valuables and only then did he let the doctor administer the anaesthetic.

The surgeons found that an inch and a half of the shin bone was destroyed. They had to insert two metal plates on either side of the tibia to connect the shattered ends. The smaller bone, the fibula, was set and allowed to heal in the cast. Skin grafts were required to close the gaping wound and, to this day, his leg looks raw and gnarled, like a twisted red stump that has been burnt in a fire.

As a result of his wound Tommy spent the next two years on his back recuperating. Unable to generate any income, he and his family had little to live on. He got no disability assistance and no help at all from the owner of the hotel. The only people who came to his aid were the patrons at the Gilmour. This rough old crowd of cronies, most of them with prison records, took up a collection and raised $9,000 to help Tommy out while he was convalescing.

The biker who shot Tommy in the leg was arrested and charged with attempted murder, but Craig, true to the code of the streets, refused to testify against him.

Two years after the shooting, when Tommy had healed and was back on his feet, he went into the taxi business. Over the next couple of years, he worked long hours and advanced himself to a position where he held the licences on fourteen cars. But with loans to pay, and a narrow margin of profit to work with, he lost all the cabs when some of the drivers cheated him out of their fares. After that, he went back to something he knew – managing bars, this time in the striptease club business.

For the next five years he managed a string of bars and in 1980 was hired at the Playmate as a combination manager, doorman and troubleshooter.

The clientele at the Playmate wasn’t as rough as the Gilmour, and that suited him fine. By this time he was thirty-three years old and he didn’t need a fight in his life every night of the week. Tommy got along well with the rounders who frequented the club. They were all guys who had been in jail, and with limited job skills, had little prospect of finding legitimate employment. Many of them were on social assistance and Tommy would cash their welfare checks, no questions asked, for a $10 service charge.

Since some of his clientele made their living doing B & Es, Tommy used the Playmate Club as a marketplace to buy and sell stolen goods. The dark, furtive atmosphere of the club made it an ideal spot for Tommy to quietly put deals together. He always carried a roll of $15,000 in cash, enough to handle almost any situation that arose. The police couldn’t prove that Tommy was doing anything illegal, but, among themselves they maintained, “Tommy Craig is moving more goods than Simpson Sears.”

The Playmate Club, off the Montreal Road facing Emond Street in Vanier

(Knuckle)

The garage across Emond Street from the Playmate Club where the stolen goods were stored

(Knuckle)

One of the biggest deals he put together was buying contraband cigarettes and liquor from the Indians on the Akwesasne Reserve. The reserve was located across the St. Lawrence River from Cornwall, Ontario. It straddled the international border from New York State into Quebec and into Ontario’s Cornwall Island. Because Akwesasne lay partially in the U.S. and partially in Canada, it afforded easy opportunity for smuggling.

Tommy made arrangements to receive 100 cases of liquor and fifty cartons of cigarettes a day. The Indians bought the contraband in the States, duty-free. They brought it across the river into Ontario and transported it by car to a meeting point near Ottawa. The transfer took place on a dead end section of the Anderson Side Road in the open countryside just southeast of the city. Three days a week Tommy would send a driver in a cube van to meet the Indians’ cars on the deserted side road. Tommy had the system down to a science. The goods were picked up at one time; the money was paid later. That way, if the police caught them in the act of transferring the material they couldn’t confiscate both the goods and the money.

The contraband found its way to many of the bars in the Ottawa area. It also found its way to a lot of private homes. Some of the liquor ended up on Parliament Hill. Tommy took orders from an employee in the legislature who came around on a regular basis. Although most of the liquor was sold to civil servants, some of it went to politicians who were sitting members of the government. One high ranking Conservative cabinet member was caught with several cases of contraband liquor in the trunk of his limousine. His driver was charged with the offense.

Tommy managed to stay clear of the law because he was clever. In the buying or selling of stolen goods or contraband, he made all the arrangements, set all the prices, paid all the bills, but he never handled any of the goods himself. He always had somebody else do that for him.

The one person that Tommy trusted to do that was Pete Bond (not his real name). Bond was a big tough kid with a background similar to Tommy’s. His troubled past included a succession of group homes and detention centres. Pete hooked up with Tommy when he was only sixteen years old. The Fat Man treated him like a son.

In 1985 Pete Bond was 6’ 2” and weighed 230 pounds. Blond haired and hawk nosed, he was a good-looking kid with a powerful physique. Like Tommy, he’d been hyperactive and uncontrolable as a child. At ten years of age he was stealing dirt bikes, repeatedly getting into fist fights, defying his mother by staying out late or not coming home at all. By the time he was thirteen, Pete was 5’11”, 190 pounds and his behaviour was worse than ever. His mother, a single parent, was faced with the impossible task of trying to control him while raising her four other children. In desperation she turned to the Children’s Aid for help and Pete was placed in a group home.

They were no more able to cope with him than his mother had been. From that first group home, he fought and kicked his way through the system until he attained the distinction of being the youngest juvenile ever remanded to the Carleton Detention Centre. After that, Pete was sent to Tommy’s old Alma Mater, the Cobourg Training School and he finally ended up in another group home in a small crossroads community south of Ottawa called Munster Hamlet. Always a bright learner and a good athlete, he hitch-hiked to high school for a while but soon tired of the regimentation. By sixteen he was out on his own supporting himself by selling pot and hash and doing B & Es.

Pete first met Tommy when he went to sell him the things he’d stolen – televisions, microwaves, blenders, all kinds of household appliances. Tommy bought the stolen goods from him only because Pete looked much older than he really was. When Tommy learned Pete’s real age and his circumstances, he took the kid under his wing and let him live in his house for six months until he could get an apartment of his own.

After that, wherever Tommy worked, Pete worked with him. In 1980 they went to the Playmate Club together. Tommy managed the place and Pete became his assistant. He was the doorman, the bouncer, the gofer. Basically, he was Tommy’s mule.

Pete soon demonstrated he was a tough bouncer and gradually took over a lot of the fights in the bar. Like Tommy, he was a good fighter, and had the scars over his eyebrows and the marks on his knuckles to prove it. It wasn’t long before he was carrying a big wad of cash and doing his own buying and selling of stolen goods in the Playmate. The sellers would come into the club and contact Pete. He would go outside, check their merchandise, and offer them a price at about fifteen percent of its value. They would unload their goods in an old, frame double garage across the street. The whole process took only a matter of minutes. When a buyer came along, Pete would sell him the goods from the garage at double the price he’d paid for it.

Pete also drove the cube van that picked up the contraband from Akwesasne. On Tommy’s instructions, he bought the liquor at $17 for a 60-ounce bottle and sold it for a price between $23 and $28, depending on the buyer.

With all his activities, Pete, still in his teens, was making $2,500 a week. But as fast as he made it, he spent it to pay for his lavish living expenses (he and Tommy both drove Chrysler 5th Avenues) and to satisfy his growing addictions. Besides smoking two packages of cigarettes a day and drinking his fill of beer and rum, Pete was using an ounce of cocaine a day.

Cocaine was the drug of choice for the B & E thieves at the Playmate and cocaine was the reason they were trapped in a vicious circle. The more goods they stole, the more cocaine they could buy. The more cocaine they used, the more they wanted. The more they wanted, the more goods they needed to steal.

Drugs were a contentious issue between Tommy and Pete, the one illegal commodity they disagreed about. The Fat Man had no use for drugs. He wouldn’t use them and he didn’t sell them. He felt that, besides being destructive, drugs brought too much heat from the police. Tommy didn’t want to see them around the club.

He would lecture Pete about his habit.

“Why you doing that?” Tommy would say to him. “Why you putting all your money up your nose?”

But Pete, being young and thinking he was indestructible, wouldn’t listen. He couldn’t foresee that his coke addiction would prove to be his downfall.

The Fat Man and Pete Bond were two of the new friends that Robert Whiteman made in the Ottawa clubs. Robert and Neil McLaren continued to go to other bars in the area but, as time passed, they zeroed in on the Playmate and went there about three nights a week. Robert got to know every waitress and dancer by her first name. He would sit at the bar with Neil, chatting with the bartender and anyone else who cared to listen to his jovial commentary. Neil was a perfect foil for his stories. Being talkative but often unsure of himself, he would sit and listen to Robert by the hour, laughing at his jokes and basking in the reflected glow of Robert’s sparkling personality.

At this point Neil didn’t know exactly where Robert was getting all his money. He suspected that Robert was into something illegal but he didn’t know for sure. Even if Neil had known that Whiteman was robbing banks, it wouldn’t have mattered to him. He liked hanging around with criminals. He loved to listen to their daring tales and, although he had no desire to be a crook himself, he seemed to get a vicarious thrill out of rubbing elbows with dangerous people.

On rare occasions Robert and Neil would bring their lady friends to the Playmate with them. Neil was just starting to date a new girl, Denise, who eventually became his second wife. Denise wasn’t interested in the sleazy atmosphere of the club or anything it had to offer. Janice didn’t mind the club but she didn’t like the “hoodlums” that Robert associated with when he went there. She repeatedly made it clear to Robert that she didn’t like Tommy Craig or Pete Bond.

For Craig and Bond and Neil McLaren, the feeling was mutual. None of them wanted to hurt Robert’s feelings so they wouldn’t say anything bad about Janice to his face, but when Robert wasn’t around, she was sometimes the topic of conversation.

“I don’t understand what Robert sees in her,” Tommy would complain. “She’s a miserable bitch and a phoney. She thinks she’s so educated. Why’s she speaking with that English accent or whatever it is, using them thirty-thousand-dollar words?”

Neil found Janice cold and unreceptive.

“You know, she never once invited me to their house,” he said. “I don’t care. I never feel really comfortable with her anyway.”

“I don’t give a shit about all that stuff,” said Pete. “What I don’t like, is she’s pushy. She’s got too fucking much to say.”

“That’s what I mean,” Tommy replied. “She’s got too fucking much to say. How the hell does Robert put up with that shit?”

Neil was more conciliatory. “Well, you can’t blame her for speaking her mind, I mean Robert is out a lot and ... “

“Ah, horseshit!” Tommy would say and the conversation would gradually move on to something else. These defamatory conversations about Janice were not rare among the three of them.

There were others that Robert met at the Playmate Club, but these three, Tommy Craig, Pete Bond and Neil McLaren, were the closest to him. He met with them almost nightly. While the music pulsed and the girls ground out their crude routines, Robert and his pals would belt back the liquor and watch the quick deals for fast money being made in every corner of the room. As 1985 unfolded, this was the milieu in which Robert immersed himself.