Destiny can throw down a pretty sparse trail of popcorn for you to follow.

Spring slinks its way into northern Minnesota and finds there’s still nothing vertical rising from the cabin floor. It’s not like we’ve been cutting bait this whole time. Getting the driveway in, the electricity down the hill, and the floor framed have all been essential. But a cabin needs walls and a roof.

I order lumber, head north, and start whacking together the first wall. I’ve built the cabin so many times in my head that my only blueprint is a smudged sheet of graph paper tucked in my back pocket. We’ve decided to build the walls using 2×6s. This gives us a thicker cavity for insulation: 6-inch stuff with an R-value of 19, instead of the R-value of 13 you get in 2×4 walls. Two by six construction will not only make the cabin more energy efficient in the long run, but the walls will be heavier in the short run.

Using the floor as a gigantic workbench, I build the 16-foot-long, 12-foot-high front wall. It contains a mammoth structural header to support the wall and roof over the opening for the 9-foot patio door. The header alone pushes 100 pounds. The conventional way to lift a wall after it’s built is to first toenail the bottom plate along a chalk line snapped on the edge of the floor. You use a pry bar to slightly lift the top of the wall so you can slip a few 2×4 blocks under it, providing space for your fingers when you start lifting. You lay some long 2×4s in the vicinity so you can brace the ends of the wall, once it’s raised. Then in a clean-and-jerk motion, you lift the wall from horizontal to a 45-degree angle to vertical in a motion resembling the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima. Normally you do this with a crew of three or four, but this element is something I sorely lack. No problem.

I get everything ready, then take a deep breath and go for the dead lift. When I was a twenty-five-year-old young buck carpenter in Denver, I built entire houses with just one other person. I lifted 30-foot-long walls and hauled trusses up two or three stories by brute force. It doesn’t register that I’m a quarter of a century older until I start lifting the wall. I wrestle it up knee-high and stop. Oof da — wood’s gotten heavier over the last couple decades, eh?

I let the wall slam back down. Clearly I need to depend on physics more than physique. I cut a pair of 3-foot-long 2×4s, grunt one corner of the wall high enough to prop the support under it, then go to the other end, lift and put the other support under that end. This I can barely handle, but the wall is moving in the right direction. I cut 5-foot-long 2×4s, repeat the same procedure, and the top of the wall swings upward another 2 feet. Better. Higher. The angle of the wall is getting to a point where the bottoms of the next pair of supports might kick out from under the rising wall. I cut a metal joist hanger in half and nail the halves, pointy end down, to 7-foot 2×4s and lift one corner again. The points dig into the subfloor so the support can’t slide. This is working pretty slick. This is genius. I start lifting the other end so I can install the other support, and suddenly my world is spinning. The wall is twisting and falling. I dive out of the way, and the 500-pound wall spins and crashes to the floor. The header misses my head by inches. The nails holding the bottom plate have given way, creating a twisting, out-of-control wall. I am within inches of becoming construction roadkill. I assess the damage: torn pants, gashed knee, bruised ego, wall back flat on the floor but now teetering half off the deck, heart rate about 600.

The good part about working alone is there’s no one to see your clumsiest moments. The bad part is if you really screw up, you can get yourself into serious trouble; even into the everafter. I dismantle the wall to make it half as heavy, then stand it in pieces. Lesson learned. I’m fifty-ish, out of shape, working alone. I get it.

The remaining 12- and 16-foot-tall walls I tackle with Goldwater-like conservatism. I build the walls in manageable sections and stand them sanely. Over the course of several days I get all the exterior walls stood and braced. I hand nail everything. I have air equipment I could use to speed things up, but the grind of the compressor, the pow-pow-pow of the nail gun, and the way hearing protection makes you feel like you’re working inside a marshmallow seem out of place in Crystal Bay.

These walls, while not glamorous, are the skeleton. Every other component will be hung from, run through, stuffed into, or nailed to it. It receives no glory, no accolades, no soft strokes of admiration. When the last piece of drywall is hung, you won’t even be able to tell this skeleton is there. But it’s what makes a cabin, a cabin; so essential that when God started fiddling around with his second human being he didn’t start with a heart, muscle, or brain. He started with a part of the skeleton: the rib.

In a standard house wall, the studs — as well as floor joists and roof rafters — are positioned every 16 or 24 inches; this pattern is usually disturbed only when punctuated by a window, door, or interior wall. The numbers 16 and 24 in the world of construction are, if not magical, efficient: Four studs spaced at 16 inches or three studs spaced at 24 inches create the perfect home for standard 48-by-96-inch sheets of plywood, drywall, oriented strand board, sheet siding, and other paneling. Batts of insulation are designed to fit snugly in these 16- and 24-inch spaces. Most other building materials — siding, moldings, trim, hardwood flooring, carpet, and vinyl flooring — come in 8-, 12- and 16-foot lengths so they too can take advantage of these efficiencies. Even many tools — tape measures (with their tick marks at 16-inch intervals), drywall squares (with their 4-foot-long arms), framing squares (with their 16- and 24-inch legs) — are designed around these golden numbers. There is a rhythm, a pattern, a logical economy. But this cabin is so cut up by pockets for floor beams and openings for windows, the pattern is hard to detect. It’s a lot of head scratching and oddball spacing, and while I’m not able to take full advantage of standardized measurements, I’m glad to have them.

If you go back far enough you’ll discover standard measurements weren’t developed by a task force, but over time. The original “inch” was based on the width of a person’s thumb (or, if you were King Edward in 1324, the length of “three barley corns, round and dry”), the “foot” was based on (no great surprise) the length of a man’s foot, and the “yard” was based on the distance between the tip of the middle finger on an outstretched arm and the tip of the nose. While it was impossible to misplace these measuring devices, discrepancies in lengths were a given. I would guess if you wanted your money’s worth back then when building you would hire tall carpenters with large feet and thumbs.

Most new houses today are “platform framed,” meaning you build in layers. You build a floor, raise a set of 8-foot walls on top of that, build another floor (or roof) and keep heading upward. Every component, whether it’s a 2×4 or a sheet of plywood, is easily carried by a single person. You always have a platform to work from, and things are rarely more than 2 feet above your head.

Walls in older homes, as well as in our cabin, are “balloon framed,” where the studs stretch continuously from bottom to top, from foundation to roof. Floors in between are “hung from” the walls. The term “balloon frame” originated in the mid-1800s when the transition was being made from building houses from logs and hefty timbers to building them with 2×4s sheathed with boards. Skeptical carpenters thought the new method so flimsy that houses framed this way would blow away — like a balloon.

We balloon-frame the cabin, not for nostalgia but for strength. The floor that links the tall sides of the cabin together will prevent the weight of the roof — in a perpetual state of trying to do the splits — from forcing the second-floor knee walls outward.

(L) Stick and platform framing; (R) Balloon framing

Kat comes up for a long weekend. After six years my heart still bungee jumps when I see her low-gearing it down the driveway. One of our missions is to heft the 200-pound salvaged floor beams in place. Again, what Kat lacks in arm strength she makes up for in fortitude. She insists on carrying and installing her half of the beam. I watch her with her tool belt on, hoisting beams, straining, pounding nails in whack after whack, converting to the two-handed swing when she’s exhausted. I see nothing but strength. Sisu, the Finns call it.

Kat is constantly pushing for more windows. I think the cabin, with a 9-foot patio door, 5-foot picture window, two skylights, and a dozen other windows is already approaching greenhouse status. Kat keeps trying to picture the views. “I want to see the lake when I’m chopping carrots.” “Wouldn’t it be nice to see cars when they drive down the driveway?” “I’d love to see that big pine when I’m sitting on the couch.” She wants another kitchen window, which will open the view but in our small kitchen will eliminate the option of even one upper cabinet. For Kat, me, and Oma Tupa, it’s hunt, peck, and compromise. And we always find, if we talk long enough, if we listen long enough, if we think long enough, we find a solution we can both live with. We find a way to make an extra window fit — we’ll figure out where the dishes go later.

And herein lies both the danger and beauty of building with only a smudged piece of graph paper in your back pocket. With an eighteen-page, architecturally drawn blueprint — (the road map for building most houses) — changes are difficult to coordinate. If something changes here, it changes something else over there. Midstream alterations become expensive; too many can slow the project down and throw off the schedule. The contractors, scheduled to finish the project like a well-choreographed dance troupe, begin to step on one another’s toes. But with a graph paper print and no client, every window, nail, and board is subject to debate.

Kat and I work long days until our arms, our patience, and the daylight fail us. The romantic, made-for-TV version of the end-of-the-day has us cooking chili over a campfire, chatting as the moon rises, then crawling into a tent overlooking the lake, rocked to sleep by the rhythm of the waves. But the real life end-of-the-day version is this: We’re bone tired, dirty, clammy, and stinky. Mostly we’ve eaten little triangular egg salad sandwiches encased in plastic from a nearby gas station. The softest thing we’ve sat on is a plastic resin chair.

So many nights we drive the seven miles to the Mariner Motel and collapse. The proprietor is grouchy at first. He’s fed up with cable installers and taconite workers tracking god-knows-what all over his carpets. His guests steal alarm clocks, wipe oily hands on bath towels, leave tables full of beer cans. Three novas short of a four-star rating, the place doesn’t draw a sterling clientele. But eventually he warms up; even talks a little fishing. And in Room 17 we revel in the orgasmic touch of a warm shower, the luxurious feel of clean sheets, and the mindless diversion of MASH reruns. Exciting? No. Sustaining? Yes.

For the last few summers I’ve gone to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) with three friends. This summer I beg off, needing the time to build. But Travis, Bruce, and Dave make an irresistible offer: the three will come work for a couple of days; then, with a week’s worth of work done in two days, I can go canoeing guilt-free. I will stay on schedule, though there is no schedule.

Their projected arrival coincides with framing the roof. Perfect. Installing the rafters and plywood is a team endeavor, but figuring out the angle and cut of the rafters is a solo activity, so I tackle this before they arrive.

Most roofs today are built using trusses. They look light and flimsy, but through the marvel of triangulation, the 2×4 and 2×6 members create a surprisingly robust roof. Truss manufacturing has literally become a science. You punch into a computer the distance the trusses need to span, the weight or load they need to carry, the pitch of the roof and other factors, and the program spits out the length and angle of every little piece that goes into the truss. The program relays this information to “smart saws” that efficiently cut the components and to “smart assembly tables,” where the pieces are arranged, then joined with metal plates hydraulically pressed into the wood.

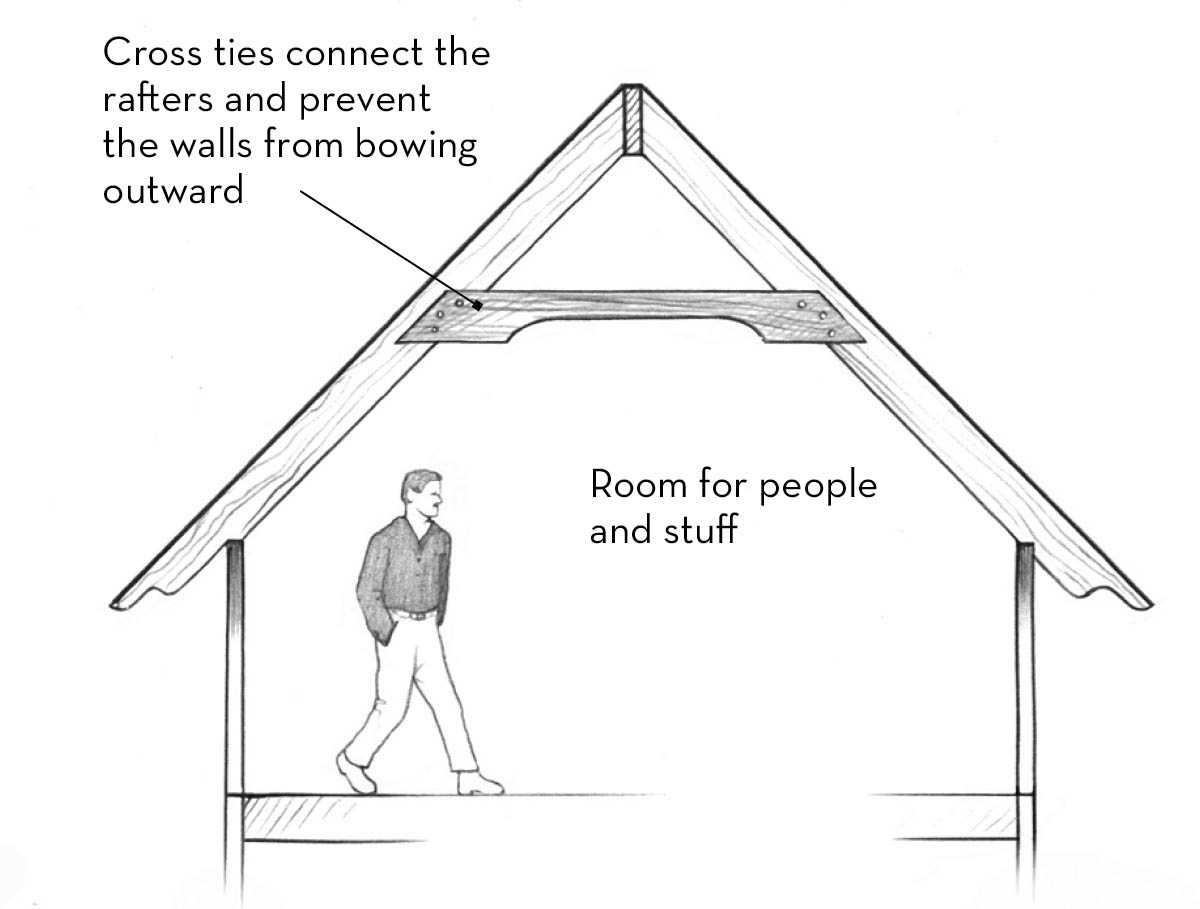

The same little pieces of wood that zigzag through each truss to give them their strength are also the source of their greatest weakness: the space within them is largely unusable. We need to take full advantage of the living space below our roof, so we opt to hand-frame the roof using 2×12s to create a vaulted ceiling. These 2×12s provide both strength and a deep cavity for installing thick batts of insulation later on.

Ordinary roof

Oma Tupa roof

I use the floor as a life-size piece of graph paper, using chalk lines to indicate the position and thickness of the exterior walls. I place one end of a 2×12 rafter-to-be on this imaginary wall, use a little geometry to determine the 45-degree pitch, and draw in the ridge board where the rafters will meet at the peak. I check and recheck, then mark the cut lines on the 2×12. This will become my pattern for marking the rest of the rafters; they’ll all be the same, either all right or all wrong. I use a circular saw to cut the angle at the peak where it will meet the ridge board and the triangular-shaped “birdsmouth” where it will rest on the walls. I trace around paint cans to create the wing-shaped rafter tails that will become the eaves and use a jigsaw for cutting those. I use the same method to figure out the rafters for the dormers, which are a different pitch, to create even more headroom in the loft. Then I mark out and cut rafters until darkness falls.

Travis, Dave, and Bruce arrive at the cabin, and the “many hands make light work” proverb turns true. Travis and Dave, nail guns in hand, bang up a clearly non-OSHA-approved scaffold made of 2×4s along one side of the cabin. By nightfall all the upper walls are sheathed and braced and most of the rafters are cut.

The next day we start in earnest on the roof. We perform high aerial feats to install the ridge board to support the tops of the rafters. Bruce, sort of the Don Rickles of cabinetmakers, fires broadsides at us while continuing to cut the rafters on solid ground. We install the rafters, oneof us securing them at the peak, the other two nailing them to the outer walls.

My calculations are right, and the rafters fit tight and true. To sheathe the rafters we carry, swing, push, and grunt the plywood, bucket-brigade style, from driveway to roof. We are frigging machines. We may be slightly rusted frigging machines, but we’re still machines. By the end of the second day, Oma Tupa, Oma Lupa has its hat on. And it’s hats off to Bruce, Dave, and Travis.

In the late afternoon of the second day, Bruce hollers from a spot below the cabin where he’s relieving himself, “Bring a level down here. Something looks waaaay strange down here.”

My first instinct is to blow him off, since Bruce is a woodworker and might consider anything 1⁄16 th of an inch out of plumb “waaaay strange.” I bring the 4-foot level down to discover that one of the nine vertical support posts he is looking at is indeed waaay strange. About 5-inches-out-of-plumb strange. Gulp.

Travis and Dave come down and are similarly appalled. One or 2 inches out of plumb — well, that you can chalk up to moderate negligence. But a post this perilously out of plumb is a felony. Worse yet, the other posts aligned with it are equally out of whack, but being shorter are not as noticeable. In my haste to build the floor and build upward, I’ve neglected to install cross bracing to keep the posts straight and plumb. This isn’t just an aesthetic problem; it’s a structural dilemma.

Carpenters love riddles, but this has no easy solution. The bottoms of the posts can’t be moved because (a) they’re buried 4 feet underground, and (b) even if we could move them, they’d no longer sit on the concrete footing pads. The tops can’t be moved because they support the corners of the floor where the weight-bearing walls sit and intersect. We halfheartedly try using a winch to rack the whole works back into place. Nada. We nail in belated cross braces and 2×4s to connect the leaning posts to the more solidly anchored crawl space walls. Dumb, dumb, dumb. If I’d spent ten minutes doing this initially, there would be no problem. Dumb, dumb, dumb. Like a tongue to a chipped tooth, I spend my hours of solitude on the canoe trip worrying about the damn posts.

Upon our return I pay the price for my haste. I toil for three days — stooped over, heart a-poundin’ — to dig three more holes by hand, pour cement, and install additional posts to support the posts with vertigo.

Leaning post dilemma

To finish framing the walls and roof of the bump-out, I enlist the services of my old Denver carpentry partner and friend, John, who lives fifty miles north. We go back thirty years. In college we consumed ungodly quantities of Boone’s Farm Apple Wine while trying to decipher the heady writings of James Joyce and John Lilly. Prompted by an experiment in Lilly’s The Center of the Cyclone, we rounded up four friends one winter evening, joined hands while encircling an elm tree in the city park, and attempted to create a “resonating group circuit” to receive interplanetary messages. What we got was cold.

John was lured to northern Minnesota years ago after forming a friendship with an old-timer named Russ who’d help build the Gunflint Trail. He bought land from Russ — forty acres on Extortion Lake — with the only access via half a mile of bushwhacking or a full mile of canoeing. John built an 8-by-8-foot starter cabin, a 16-by-16-foot final cabin, and an outhouse using the skeletal remains of a moose as the main structure. There was no electricity or telephone, and he fetched his water in five-gallon buckets from the lake. When John married, the ceremony took place on a cliff overlooking the lake, the justice of the peace paddling in by canoe. John lives in town now but hangs on to his wilderness retreat.

It was John who showed me the door to carpentry. The chain of events that put a hammer in my hand shows what a sparse trail of popcorn destiny can throw down for you to follow. I met John at Gustavus Adolphus (nickname: God-save-us, All-of us) College, a small-town liberal arts college with the emphasis on “small.” The winters were long. To break the monotony of studying for finals, we’d swipe trays from the cafeteria, wax them up with margarine, then attempt to gain enough downhill momentum to hit the snowbank by the tennis court and cross the street on the fly. But mostly it was quiet.

I selected philosophy as a major, and when my father suggested I consider a degree in a field where there were more than three job openings in the world, I selected English lit. When he pulled me aside a second time, I upped the ante to English teacher. When I couldn’t pass the foreign language requirement I defaulted to elementary education; I was a kid once, I knew how that whole thing worked. Upon graduating I landed a job at the Woods Free School in Denver — an alternative school where kids could do whatever they wanted and a third of the parents adhered to the then-popular psychology of primal screaming. After my second year of teaching I went looking for a summer gig.

About the same time John was hitchhiking to Denver for a visit and was picked up by a Vermonter, heading west to hook up with a friend of a friend, who was building houses. John wound up working with them as a laborer, and shortly after, I joined up with them, too.

When I started I knew nothing about carpentry. I didn’t know walls were built flat, then raised into position. I didn’t know how to change a saw blade. And I surely didn’t realize how physically demanding the job would be. For the first week I couldn’t open my right hand in the morning, it was so knotted up from swinging a twenty-eight-ounce hammer. And my left hand was clublike from whacking it with a twenty-eight-ounce hammer. My knees felt like they’d been transplanted from a camel. But by the end of the summer I had my own framing crew. I was making twice as much money and facing half as much stress (and screaming) as I did as a teacher, so I stuck with carpentry. In short, I did what all good hippies did in the seventies: went to college, got a degree, then became a carpenter.

John returned to Denver, and we became a two-man framing crew. We became so in synch, we could frame a house in three days. On days when we were in the flow we could make fifteen dollars an hour and had life by the gonads. We worked outside and were lean, tan, and, though the word probably hadn’t been coined back then, ripped. We were our own bosses. We could wear what we wanted and work as much as we wanted. On lunch breaks we could smoke, eat Twinkies, and exchange tales of bizarre construction accidents — and chances were good the concrete crew working next door would swing over and do the same. The Jimmy Jingle girl who pulled up to the job site at noon peddling sandwiches, Coke, and Marlboros wore a bikini top and was bad at making change. We could sneer at those cruising to office jobs along I-25, imagining they were staring back at us in jealous longing. We were modern-day cowboys who rode into town in a ’56 Dodge Power Wagon, slinging our hammers. We swaggered. If we cut ourselves we pinched the wound tight with duct tape and kept working. Hearing, eye, and fall protection were for wimps. Life was grand, and we’ve both hovered around the carpentry life since then.

John and I complete the small loft above the entryway, then hand-cut and install the rafters. We sheathe the roof with plywood and get the tar paper down. Things go like clockwork. Our rhythm, unspoken language, and carpentry ESP, established years ago, remain.

Kat and I decide to build the stairway now, though there’s a risk the exposed fir stringers will get beat up while we build the rest of the cabin. But it’s better the stringers than the knees. Carpentry is a young person’s sport. It builds you up physically for the first few years, then starts tearing you down.

The first few steps of the stairway are triangular and fan like cards in a bridge hand, then launch into a straight shot to the loft. Stairways are part math, part sawdust. Each rise, or the height of each step, should be 81⁄4 inches or less. The run or width should be 9 inches or more. Rule of thumb says, combined, the rise and run should be between 17 and 19 inches; it’s what the human stride comfortably handles. The heights of the steps should be within 1⁄4 inch of each other or the rhythm that feet develop while ascending or descending gets broken. Space is at a premium, so we cheat a little on the math.

The interior framing goes quickly because there are only three walls: two to create the bathroom and one to create the entryway closet. That’s it. Everything else is wide open.

The rough shell of the cabin is complete. Kat and I stand back on the driveway. We finally get a feel for how it fits with the land and our fantasies. We note that the staggered roofs make it look like a plywood seagull flapping its wings. It has a snug yet open feel; when we look through the arched window in the back, we can see Lake Superior through the arched window in the front.

From the kitchen, bathroom, and loft windows, we’re able to frame the views of the lake and woods. We lie on the second floor where our bed will be and realize we’re high enough to see the splash from the thumper hole. Things that even the best blueprint can’t show — the vibe, the texture, the sense of wonder — become tangible. We love what we’ve created nail by nail, compromise by compromise, blister by blister.