You can’t buy happiness by the square foot.

When people find we’re designing a cabin, the questions progress in a certain order.

“Where’s the lot?”

“Seven miles north of Silver Bay, two miles beyond Palisade Head.”

“What’s the land like?”

“Three acres with manic-depressive shoreline, terrain like Everest, one almost-level spot the size of a basketball court.”

“What kind of cabin will you build?”

“Small” is the only unqualified answer we can muster. If pressed for a style, we think something along the lines of “funky, seaside, carpenter-Gothic with Danish-style Arts and Crafts leanings” — a style you’d be hard pressed to find in any Architecture 101 book.

Cooks and designers have more in common than an insatiable appetite to star in their own reality TV shows. Those who cook create recipes; those who design create floor plans. Those who cook use ingredients; those who design use materials. And in both cases you find you can wind up with very different end products depending on how you combine the same fundamental materials. Victorian and ranch homes are both built with 2×4s; soufflés and scrambled eggs are both made with eggs. It just depends on how much of each ingredient you use, when you add it, what you combine it with, what spice you add, and how much care you take in the making. Good designers, like good chefs, snatch ingredients from different eras and disciplines.

So while “contemporary,” “Queen Anne,” “Craftsman,” and “ranch” are all nice pigeonholes, few houses follow a style rigidly. “Victorian” isn’t a style mandated in heaven but rather an evolving group of characteristics — turrets, bold colors, gingerbread millwork — that, by consensus, got a name hung on it. Surely there are pure examples of given architectural styles. Monticello is the essence of Greek Revival. The “painted ladies” of San Francisco scream Victorian. The houses of Levittown define the ranch style. But most houses are mutts.

So when we start designing Oma Tupa we don’t start with a particular style but rather with a notion of what we like, need, and can afford. We want our cabin to be comfort food with an edge. We start doodling, borrowing an idea here and there, ripping pages out of magazines. Some of the design ideas are dictated by nature, as in, “Wow, we gotta frame that view with a gigantic window.” Some are dictated by odds and ends we run into, as in, “Hey, Kat, there are some great old beams for sale cheap!” A design slowly evolves.

In his book The Cabin, architect and cabinologist Dale Mulfinger outlines what he feels are the minimum qualifications for a dwelling to be considered a cabin:

These words jibe with where we’re headed. We have an awe-inspiring site. We want small. We want simple. We want comfortable.

In Cabins David and Jeanie Stiles extol: “The cabin is a simple, sacred place where food and drink always taste better, where music sounds brighter, where evenings with loved ones linger longer into pleasure, where sleep is deep and dawn is fresh with wonders we’ve elsewhere forgotten.”

They got it right, too.

The average house built in the United States has 2,392 square feet. According to the National Association of Home Builders, that average house contains 13.97 tons of concrete, 13,127 board feet of framing lumber, 15 windows, 3 toilets and 3,100 square feet of shingles. There’s plenty of space for everything and everybody. If you fight with your spouse you can go to your corners.

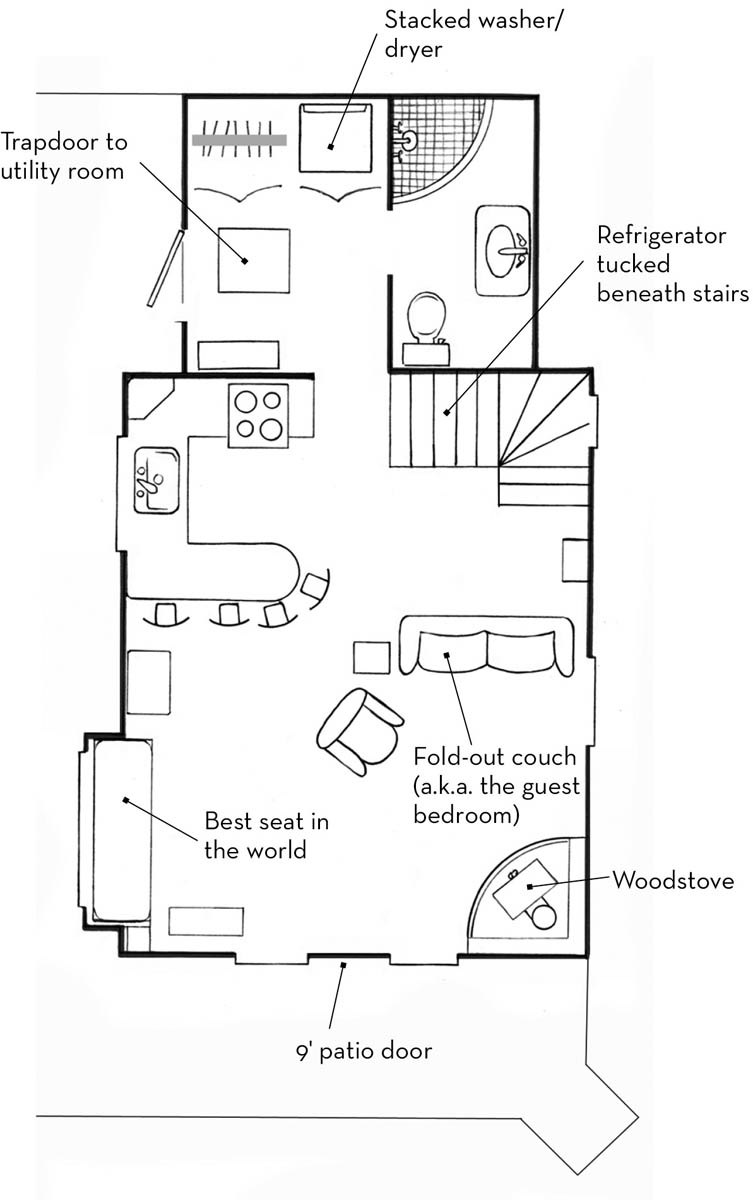

But not so with a cabin with a footprint of 440 square feet; 600 square feet when you throw in the loft. A 16-by-20-foot cabin is 21⁄2 sheets of plywood running end to end and 4 sheets running side by side. It’s a space you can cross the short way in five strides. Doors are at a premium because there’s no place for them to swing. If you feud in a cabin that small, you’ve got no place to go. It’s a marriage counselor made of drywall.

A 16-by-20-foot cabin is small — but not as small as we (or I should say I) had originally planned. The idea was to build something small and fast for starters — something that could later become a guesthouse. We’d build the real cabin later. The early doodles presumed a 12-by-12-foot cabin; a dwelling that could be built in a summer’s worth of weekends. The kitchen was a Coleman stove, wet bar sink, and dorm-size refrigerator. The bathroom was a toilet, with the water heater and pressure tank stacked in one corner. The bathroom sink was the kitchen sink. There was a small loft, accessed by a ladder. There was one door and six windows.

At 144 square feet it was similar to the cabin Thoreau built in 1845 for $28.12. But while he only needed room for himself, a bed, a writing desk, and three chairs named Solitude, Friendship, and Society, our needs weren’t quite as simple.

Kat was fine with the graph paper doodles of the 12-by-12-foot cabin. But when she took measuring tape and masking tape in hand and laid things out on our living room floor at home, her support of “small” got smaller. When she realized she’d nearly be able to load the woodstove from the toilet, the dissent began in earnest.

Main floor plan

Freud, move over, because it was Kat’s and my very different childhoods that forged our attitudes toward size. I grew up in a typical middle-class Minneapolis suburban house. I had my own bedroom. We had a single-car garage, a kitchen with a snack bar, and one and a half bathrooms — nothing ostentatious, but absolutely comfortable. Kat grew up in a family of exceedingly modest means in the less than bucolic town of Bemidji, Minnesota. The house she grew up in was one her father bought, then moved to the lot where it still stands and where her mother lived until a few years ago. For the first year water came from a hand pump beside the kitchen sink. Her bedroom was a compact attic shared with two sisters. The whole thing was perched on a bump-your-head-if-you-stand-up basement. Kat had had her fill of small and dark. She had no intentions of going backward, and a cabin this small rang of reverse gear.

So we go up in size, working in 4-foot increments, because building materials work efficiently in 4-foot increments. We burn up the graph paper. We arrive at a size that’s still compact but has more breathing room.

I tack together a bread box–size version of the cabin. We cut little windows out of cardboard and tape them here and there. Model cabin in hand, we stomp around the land positioning it in different places and orientations. I use a machete to thin out a few dozen small birches; at a landscaping center in the cities they’d have a price tag of $129 each. Funny how that works. Squinting helps us envision the views we’d have from each window and room. We set up a tall stepladder so we can try to picture the views from the loft. If we rotate the cabin clockwise we get a better view of the lake from the living room, but a worse view from the loft. If we move it away from the lake, the land becomes flatter and easier to build on, but hmmmm, that means we’re farther from the lake. We tweak the design based on what we see and feel.

This is no small decision. This will be the first dwelling on this land. Ojibwe had lived in the area for over 600 years, but it’s doubtful they would have built one of their birch-bark wigwams on this plot overlooking Gitchi (big) Gummi (water) — too damn steep. French explorers, trappers, and missionaries began roaming the area in the late 1600s, but if any of them had wanted to build a shelter, they would have stomped the quarter mile to the flat, sensible terrain of the old campground. Swedish and Norwegian immigrants began flocking to the area in the 1800s, but they too would have settled on land where their fishing boats and fishing sheds had easier access to the lake. The lumberjacks who arrived in the 1880s surely would have logged the 100-foot-tall white pine from the land, part of the 67 billion board feet of lumber harvested in Minnesota during the boom. And while the steep land would have made it easy to slide logs into Superior for the trip to the mill, the loggers would have rested their seesaw-weary bones in one of the logging camps near Beaver Bay. We were the first people unhinged enough to give it a whirl.

Designing the cabin is an ongoing process of give-and-take, of determining priorities, of trust, of love. Kat loves to cook, so the kitchen begins claiming more square footage. I need a mini-office for writing, so the loft grows a 4-foot leg for a desk. We love the lake views, so we incorporate a window seat, decks on two sides, and lots of windows. I like old wood and architectural antiques, so we keep the plan fluid enough to accommodate discoveries. We try to strike a balance between making good use of small nooks but not making it so space efficient it feels like a Winnebago.

The stairway drives much of the design. The 40 square feet it will occupy represents a whopping 10 percent of the floor space. The headroom in the loft will be low, making it impossible to position the stairway on an outside wall where the roof slopes down to meet the second floor knee walls. Placing it in the middle of the cabin will divide the already small space into two even smaller spaces. A ladder will take up only a quarter of the space, but looking to the future, we can’t picture ourselves climbing a ladder with a cane in one hand and morning cup of coffee in the other. We doodle, erase, and rethink the overall plan — but the pencil just isn’t sharp enough.

We raise the white flag and pay a visit to Katherine Hillbrand, an architect and interior designer with SALA Architects. We’ve loved working with Katherine on past projects because she has a knack for walking the line between solid design and whimsy. She thinks architecture should be fun. She has a way of adding a few unique details that turn a good design into a great one. Her mental search engine shows her right where to go with our stair problem. On the spot she breaks out her omnipresent roll of vellum paper and electric imagination and scratches out three good options.

The one we like most has an L-shaped stairway nestled along the bathroom wall with its final ascent paralleling that of the roof. There’s not an inch of wasted space: A rollout pantry can tuck under the stairs next to a Lilliputian refrigerator. There’s a little nook that could be turned into a coffee cup shelf. And look, there’s a place on the landing for the round, stained glass parrot window impulsively bought at an antique store.

Upstairs floor plan

All the planning makes me drift back to the cabin my folks bought on Lake Waverly years before. Oma Tupa — when finished — will be the same size as theirs; both are perched on bodies of water; both are small and cozy. But they differ big time in terms of the neighborhood. The nearest dwelling to ours, Dick and Jean’s house, will be a good 800 feet away. My parents’ cabin was flanked on each side by cabins less than 15 feet away. The closeness did not play out well in their case.

On one side lived Gerold, whose hobby was building miniature cannons he entered in distance competitions with a Civil War reenactment group. He had a mini–smelting furnace situated on the property line where, on the weekends, he melted down disfigured plumbing pipe and old steering columns to make cannonballs for ammo. He tested his prototypes by picking off renegade cornstalks in the abandoned field across the road. Nothing like trying to relax not knowing when the next cannonball will rip overhead.

On the other side lived Marti and Rob; he, a three-pack-a-day grump, and she, a pathological chatterbox. She knocked on the door to chat five or six times a day. She kneweth no boundaries. When my folks sat out on the screen porch, Marti — from her screen porch — would start up conversations about milfoil weed and local traffic accidents. Sitting outside on a lounge chair became a non-option. One day, when my mother had absolutely had it, she inflated an air mattress and floated out into the middle of the lake to get away. Eyes shut, drifting on the water, she’d finally found peace and quiet at the cabin — until Marti paddled up on an air mattress, talking about the difficulties of finding good sewing patterns in a small town. My mother wondered wistfully if Gerold would ever lend out a cannon.

I’m glad we’re flanked by Dick and Jean on one side and a State 40 on the other.