31 Angela Carter, Nights at the Circus (1984)

It might be laboring the point to say Bowie knew all about traveling circuses and freak shows, from the vaudeville troupers of his Brixton childhood to the louche court over which he presided as a touring rock star. But his knowledge may well have fed into his admiration for Nights at the Circus, one of the most underrated British novels of the 1980s. It turned out to be Carter’s penultimate work: she died of lung cancer in 1992, at the age of fifty-one.

Drawing on folklore and fairy tales, Carter created spellbinding dream-realities that defy all conventional laws of time and space—a bit like glam rock, which she recognized as dandyism, “the ambivalent triumph of the oppressed.” Her stories and novels often take the form of feminist fables set in exotic landscapes where resourceful heroines battle cruel, autocratic villains. Nights at the Circus draws on the picaresque tradition: think of Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote or Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers.

Nights at the Circus whisks us to Saint Petersburg and Siberia before it’s through. But it opens in London in 1899, in the dressing room of acclaimed aerialiste Sophie Fevvers, who was (she says) hatched from an egg. This freakish giantess is telling her story to an American journalist, Jack Walser. And what a story it is—of how, as a foundling, Fevvers was raised by prostitutes and styled as their mascot, a powder-white Cockney Venus. When puberty hit, the feathery buds on her back blossomed into wings. But (she says) she remained a virgin, the only fully feathered virgo intacta in history.

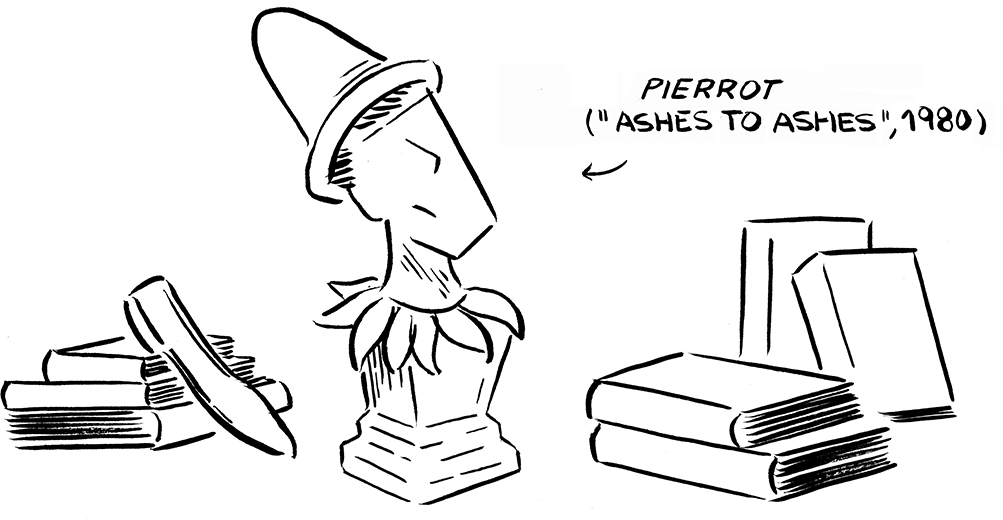

When her luck changes, Fevvers is forced to work in a different, more sordid brothel, playing a tombstone angel at the head of a naked woman on a marble slab—“Sleeping Beauty.” Then she narrowly avoids being sacrificed by a religious maniac calling himself Christian Rosencreuz, after one of the founders of Rosicrucianism (see p. 104). But she lives to tell the (tall) tale. So entranced is Walser that, even though he thinks of himself as a hard-bitten skeptic, he joins Fevvers on her Grand Imperial Tour, working as a clown alongside downtrodden Mignon, who waltzes with tigers; Monsieur Lamarck, Mignon’s abusive monkey-trainer husband; and a clairvoyant pig called Sybil, whom the tour’s manager, Colonel Kearney, consults before making any business decisions.

Is Fevvers a fraud? Does it matter? (There are obvious shades here of Lawrence Weschler’s Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder, about the Museum of Jurassic Technology—surely Fevvers’s natural home. See p. 274.) Nights at the Circus keeps us guessing even when Fevvers seems to give the game away, her beguiling, bullshitting, clever-Cockney voice swooping high and low, and sounding, at times, disarmingly like Bowie’s.

- Read it while listening to: “Look Back in Anger”

- If you like this, try: Angela Carter, The Bloody Chamber