66 Arthur C. Danto, Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective (1992)

Say what you like, Bowie wasn’t scared of a challenge. Beyond the Brillo Box is a collection of high-fiber essays by Columbia University philosophy professor Danto that for the most part take stock of pop art and its conversion of everyday items like soup cans and Brillo boxes into art. A product of the egalitarian 1960s, pop art loosened up a stuffy scene, banishing forever the atmosphere of awed reverence in which people had been encouraged to digest art.

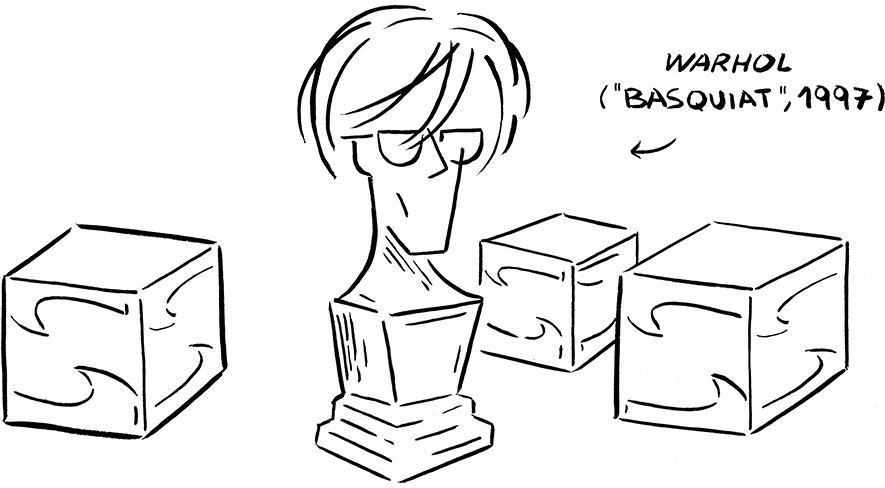

But it had a philosophical impact too. Warhol showed, as Duchamp had before him in 1917 with his urinal exhibited under the title Fountain, that you couldn’t tell what art was just by looking at it. Nor could you teach art by example. In fact, says Danto, nothing exists as art outside the context that gives it that status. One of those reasons is awareness of where an artwork “fits” historically. Because pop art exists at the point where art and reality have become indivisible, it undermines this whole approach. It has, Danto argues, reached a sort of historical end and became philosophy instead.

That still leaves the question of what art should be striving to do. Danto defends the National Endowment for the Arts’ controversial sponsorship of an exhibition of explicit photos by Robert Mapplethorpe at a gallery in Washington, DC, in 1989, arguing as Bowie would surely have done that art cannot be meaningful unless it has the freedom to dissent and give offense. In another essay, considering the symbolism of messy rooms, Danto anticipates with uncanny accuracy Tracey Emin’s 1998 breakthrough piece My Bed, genuinely Emin’s own filthy bed surrounded by the detritus of her life—condoms, vodka bottles, dirty knickers. Bowie would have loved this coincidence, as he and Emin were friends, the singer admiring in The Independent the way Emin’s work was “a celebration of personality” which deliberately lacked “what some critics would call deeper context.”

- Read it while listening to: “Andy Warhol”

- If you like this, try: Cynthia Freeland, But Is It Art? An Introduction to Art Theory