86 R. D. Laing, The Divided Self (1960)

“We go every fortnight and we take a hamper of sandwiches and apples, new shirts, and fresh stuff. Take his laundry. And he’s always very happy to see us but he never has anything to say. Just lies there on the lawn all day, looking at the sky.”

—David Bowie on visiting his half brother, Terry, in the hospital

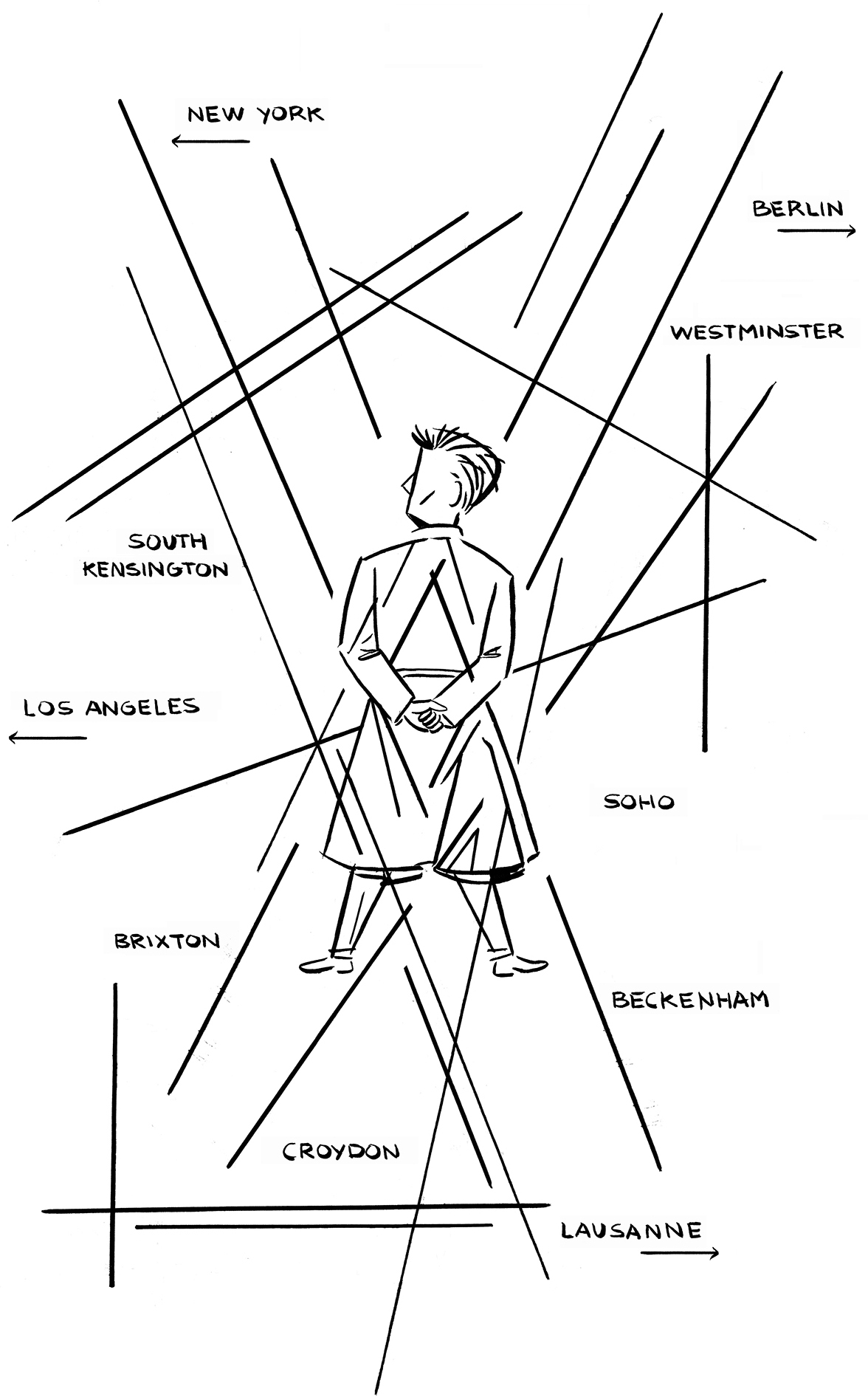

In 1960s Britain, the standard method for treating mentally ill people was to isolate and drug them in vast asylums like south London’s now demolished Cane Hill, immortalized in cartoon form on the cover of the US version of The Man Who Sold the World. Bowie’s schizophrenic half brother, Terry, spent long periods at Cane Hill in the course of his abbreviated life.

To the Scottish psychiatrist Ronald Laing, this approach wasn’t just inhumane but wrongheaded. He believed social context was all-important; that abnormal family relationships, especially, could provoke in some children “ontological insecurity,” a fragile sense of self that leads eventually to psychosis. Bowie seems to have worried about the normality of his own childhood setup: “I think there’s an awful lot of emotional, spiritual mutilation goes on in my family,” he told Interview, perhaps remembering the way Terry, ten years his senior, was browbeaten and excluded by Bowie’s father (Terry’s stepfather). Bowie revealed to Crawdaddy magazine in 1977 that Terry “cried an awful lot at an age when I had been led to believe that it was not a particularly adult thing to do.” Mainstream biological psychiatry held that there was no point trying to communicate with schizophrenics. Laing showed that, on the contrary, it was vital to make efforts to understand their “word-salad” (confused speech consisting of random words) because it might have something to tell us, perhaps even the “truth” of their predicament.

As the 1960s rolled on, Laing became a leading light in the “antipsychiatry” movement, committed to altering the consensus view of mental disorder and ending the practice of compulsory hospitalization. A shamanic figure within the counterculture—a two-page interview with Laing in the July 4, 1969, issue of International Times gets higher billing on the cover than one with Mick Jagger—he used LSD to treat Sean Connery for stress and hung out with Paul McCartney at the World Psychedelic Center in Belgravia. In 1967 he was a speaker at the Dialectics of Liberation conference at London’s Roundhouse, a gathering of the era’s alleged finest minds which sought to “solve all the problems of the planet,” as one journalist archly put it. Laing also attracted a glamorous, cultured crowd to happenings at Kingsley Hall, his commune-like “safe haven” in East London.

Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett, admired hugely by Bowie, triggered his latent psychosis by taking vast quantities of LSD. His manager Peter Jenner took him to Laing for treatment but the session wasn’t a success. When Bowie writes about how he’d rather hang out with “madmen” than perish with the sad men roaming free, he’s echoing Laing’s belief that our “normal” state is a rejection of our ecstatic potential. Laing identifies schizophrenia as a state of transcendence that ordinary squares don’t understand, a tributary of the nostalgic, childhood-obsessed endless-summer dream state celebrated in acid reveries such as the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever,” Pink Floyd’s “See Emily Play” (covered by Bowie on Pin Ups) and pre-RCA Bowie efforts like “When I’m Five” and “There Is a Happy Land.”

In middle age, Bowie would confirm what many had long suspected: that his restless creativity was a way of harnessing a mania that might otherwise present as madness: “One puts oneself through such psychological damage in trying to avoid the threat of insanity,” he admitted to the BBC in 1993. “I felt I was the lucky one [in my family] because I was an artist and it would never happen to me because I could put all my psychological excesses into my music and then I could always be throwing it off.”

- Read it while listening to: “See Emily Play” (cover of Pink Floyd song)

- If you like this, try: R. D. Laing, The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise